End of slavery in the United States of America

The United States of America historically allowed the enslavement of human beings, most of them Africans and African Americans who were transported from Africa during the Atlantic slave trade and whose freedom was taken as a result. The institution of slavery began in the United States in the 16th century under British colonization of the Americas, and was ended with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865.

Background[]

On 22 August 1791 started the Haitian Revolution, and it concluded in 1804 Haiti with the Independence of Haiti, with the independence ended the slavery in Haiti and it became the first country in the planet that abolished slavery.[1]

In 1804 Alexander von Humboldt visited United States and expressed the ideas that slavery was not the way to treat it's citizens, during Thomas Jefferson presidency, this ideas were expanded by the followed generation of American politicians, writers and members of the clergy, among them can be namedRalph Waldo Emerson and Abraham Lincoln.[2][3][4]

The abolitionism in the United States movement sought to end gradually or immediately slavery in the United States. It was active from the late colonial era until the American Civil War, which brought the abolition of American slavery through the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Civil war[]

The civil war in the United States from 1861 until 1865 between states supporting the federal union ("the Union" or "the North") and southern states that voted to secede and form the Confederate States of America ("the Confederacy" or "the South").[a] The central cause of the war was the status of slavery, especially the expansion of slavery into newly acquired land after the Mexican–American War. On the eve of the Civil War in 1860, four million of the 32 million Americans (nearly 13%) were black slaves, mostly in the South.[5]

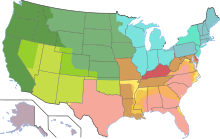

The practice of slavery in the United States was one of the key political issues of the 19th century; decades of political unrest over slavery led up to the war. At the start of the Civil War, there were 34 states in the United States, 15 of which were slave states. 11 of these slave states, after conventions devoted to the topic, issued declarations of secession from the United States and created the Confederate States of America and were represented in the Confederate Congress.[6][7] The slave states that stayed in the Union, Maryland, Missouri, Delaware, and Kentucky (called border states) remained seated in the U.S. Congress. By the time the Emancipation Proclamation was issued in 1863, Tennessee was already under Union control. Accordingly, the Proclamation applied only in the 10 remaining Confederate states. During the war, abolition of slavery was required by President Abraham Lincoln for readmission of Confederate states.[8]

The U.S. Congress, after the departure of the powerful Southern contingent in 1861, was generally abolitionist: In a plan endorsed by Abraham Lincoln, slavery in the District of Columbia, which the Southern contingent had protected, was abolished in 1862.[9] The Union-occupied territories of Louisiana[10] and eastern Virginia,[11] which had been exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation, also abolished slavery through respective state constitutions drafted in 1864. The State of Arkansas, which was not exempt but which in part came under Union control by 1864, adopted an anti-slavery constitution in March of that year.[12] The border states of Maryland (November 1864)[13] and Missouri (January 1865),[14] and the Union-occupied Confederate state, Tennessee (January 1865),[15] all abolished slavery prior to the end of the Civil War, as did the new state of West Virginia, separated from Virginia in 1863 over the issue of slavery, in February 1865.[16] However, slavery persisted in Delaware,[17] Kentucky,[18] and (to a very limited extent) in New Jersey[19][20] – and on the books in 7 of 11 of the former Confederate states.

Emancipation Proclamation[]

The Emancipation Proclamation was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on September 22, 1862, during the Civil War. The Proclamation read:

- That on the first day of January in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.[21]

On January 1, 1863, the Proclamation changed the legal status under federal law of more than 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states from enslaved to free. As soon as a slave escaped the control of the Confederate government, either by running away across Union lines or through the advance of federal troops, the person was permanently free. Ultimately, the Union victory brought the proclamation into effect in all of the former Confederacy.

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution[]

The Thirteenth Amendment (Amendment XIII) to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. The amendment was passed by Congress on January 31, 1865, and ratified by the required 27 of the then 36 states on December 6, 1865, and proclaimed on December 18. It was the first of the three Reconstruction Amendments adopted following the American Civil War.[22]

President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, effective on January 1, 1863, declared that the enslaved in Confederate-controlled areas were free. When they escaped to Union lines or federal forces—including now-former slaves—advanced south, emancipation occurred without any compensation to the former owners. On June 19, 1865—Juneteenth—U.S. Army general Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas, to proclaim the war had ended and so had slavery (in the Confederate states). In the slave-owning areas controlled by Union forces on January 1, 1863, state action was used to abolish slavery. The exceptions were Kentucky and Delaware, where slavery was finally ended by the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865.

Juneteenth[]

Juneteenth is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the emancipation of African-American slaves. It is also often observed for celebrating African-American culture. Originating in Galveston, Texas, it has been celebrated annually on June 19 in various parts of the United States since 1865. The day was recognized as a federal holiday on June 17, 2021, when President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act into law.[23][24] Juneteenth's commemoration is on the anniversary date of the June 19, 1865, announcement of General Order No. 3 by Union Army general Gordon Granger, proclaiming freedom for slaves in Texas,[25] which was the last state of the Confederacy with institutional slavery.

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), emancipation came at different times to various places in the Southern United States. Large celebrations of emancipation, often called Jubilees (recalling the biblical Jubilee in which slaves were freed) occurred on September 22, January 1, July 4, August 1, April 6, and November 1, among other dates. In Texas, emancipation came late: enforced in Texas on June 19, 1865, as the southern rebellion collapsed, emancipation became a well known cause of celebration.[26] While June 19, 1865, was not actually the 'end of slavery' even in Texas (like the Emancipation Proclamation, itself, General Gordon's military order had to be acted upon) and although it has competed with other dates for emancipation's celebration, ordinary African Americans created, preserved, and spread a shared commemoration of slavery's wartime demise across the United States.[25]

Slavery in the 21st century[]

Since the abolition of slavery in the United States in 1865 many other events have enforced the effort to eliminate any other forms of slavery, in 1890 took place the Brussels Conference Act – a collection of anti-slavery measures to put an end to the slave trade on land and sea. In 1904 was signed the International Agreement for the suppression of the White Slave Traffic. In Slavery Convention is ratified.

Even when slavery is no longer promoted or tolerated and became illegal during more than one century, many criminal organization have being practicing human trafficking and slave trade, for this reason human trafficking have became a federal crime. In 2000 was signed the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 and in 2014 was created the Human Trafficking Prevention Act would amend the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 to require training for federal government personnel related to trafficking in persons.[27] On 12 Dec 2000 was signed the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children in the United Nation Organization and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime was in charge of implementing the protocol. In 2002 was founded the Polaris Project[28] Polaris is one of the few organizations working on all forms of trafficking, including supporting survivors who are male, female, transgender people and children, US citizens and foreign nationals and survivors of both labor and sex trafficking.[29]

Media[]

- In the documentary film 13th is explored the "intersection of race, justice, and mass incarceration in the United States;"[30] It is titled after the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, adopted in 1865, which abolished slavery throughout the United States and ended involuntary servitude, but slavery have been silently perpetuated since that time until the present, through criminalizing behavior and enabling police to arrest poor freedmen and force them to work for the states and the prevalence of massive "carceral states" managed by for profit prison corporations that have created the current carceral capitalism in the United States.[31]

- Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North, is a 2008 documentary film that focuses on the descendants of the DeWolf family, a prominent slave trading family who settled in Bristol, Rhode Island, who trafficked Africans from 1769 to 1820, and the legacy of the slave trade in the North of the United States.[32][33]

See also[]

- Slavery in the United States

- Timeline of abolition of slavery and serfdom

- History of civil rights in the United States

- Abolitionism

- Juneteenth

- History of unfree labor in the United States

- Slave Trade Act

- Slavery Abolition Act 1833

- Abolitionism in the United Kingdom

- Slavery Abolition Act 1833

- International Agreement for the suppression of the White Slave Traffic

- Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery

- Slavery in the 21st century

Notes[]

- ^ A formal declaration of war by the United declaration of war was never issued by either the United States Congress nor the Congress of the Confederate States, as their legal positions were such that it was unnecessary.

References[]

- ^ Copied form the article Abolitionism

- ^ "Alexander von Humboldt to Thomas Jefferson, 12 June 1809".

- ^ "The Invention of Place: Alexander von Humboldt and the Meaning of Home « Journal of Sustainability Education".

- ^ "'Alexander von Humboldt and the United States' Review: American Cosmos - WSJ".

- ^ McPherson 1988, p. 9.

- ^ Martis, Kenneth C. (1994). The Historical Atlas of the Congresses of the Confederate States of America, 1861–1865. Simon & Schuster. p. 7. ISBN 0-02-920170-5.

- ^ Only Virginia, Tennessee and Texas held referendums to ratify their Fire-Eater declarations of secession, and Virginia's excluded Unionist county votes and included Confederate troops in Richmond voting as regiments viva voce.Dabney, Virginius. (1983). Virginia: The New Dominion, a History from 1607 to the Present. Doubleday. p. 296. ISBN 9780813910154.

- ^ Guelzo, Allen C. (2018). Reconstruction : a concise history. Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-086569-6. OCLC 999309004.

- ^ American Memory "Abolition in the District of Columbia", Today in History, Library of Congress, viewed December 15, 2014. On April 16, 1862, Lincoln signed a Congressional act abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia with compensation for slave owners, five months before the victory at Antietam led to the Emancipation Proclamation.

- ^ "Reconstruction: A State Divided".

- ^ "Education from LVA: Convention Resolved to Abolish Slavery". Archived from the original on 2016-03-30.

- ^ "Freedmen and Southern Society Project: Chronology of Emancipation". www.freedmen.umd.edu. University of Maryland. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ "Archives of Maryland Historical List: Constitutional Convention, 1864". November 1, 1864. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ "Missouri abolishes slavery". January 11, 1865. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ "Tennessee State Convention: Slavery Declared Forever Abolished". The New York Times. January 14, 1865. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ "On this day: 1865-FEB-03". Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ "Slavery in Delaware". Slavenorth.com. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ Harrison, Lowell H.; Klotter, James C. (1997). A New History of Kentucky. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky. p. 180. ISBN 0813126215. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

- ^ "Slavery in the Middle States (NJ, NY, PA)". Encyclopedia.com. July 16, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Geneva. "Legislating Slavery in New Jersey". Princeton & Slavery. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ "Emancipation Proclamation (1863)". Ourdocuments.gov. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ Kocher, Greg (February 23, 2013). "Kentucky supported Lincoln's efforts to abolish slavery — 111 years late | Lexington Herald-Leader". Kentucky.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ Cathey, Libby (June 17, 2021). "Biden signs bill making Juneteenth, marking the end of slavery, a federal holiday". ABC News. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ President Biden [@POTUS] (June 17, 2021). "Juneteenth is officially a federal holiday" (Tweet). Retrieved June 18, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ a b Gates Jr., Henry Louis (January 16, 2013). "What Is Juneteenth?". PBS. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ^ "Juneteenth and the Emancipation Proclamation". JSTOR Daily. June 18, 2020. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ "H.R. 4449 - Summary". United States Congress. 24 July 2014. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ "Fighting modern slave trade | Harvard Gazette". News.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ^ "Katherine Chon and Derek Ellerman: Fighting Human Trafficking | USPolicy". Uspolicy.be. 2009-03-09. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ^ Manohla Dargis, "Review: '13TH,' the Journey From Shackles to Prison Bars", The New York Times, September 29, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2017

- ^ Copied from the article 13th (film)

- ^ "Synopsis". Traces of the Trade. 2008-06-14. Retrieved 2020-04-29.

- ^ Copied from the article Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North

- Slavery in the United States