Eumycetoma

| Eumycetoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Madura foot[1] |

| |

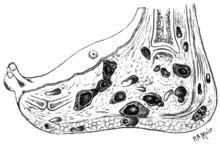

| Eumycetoma Foot | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases[2] |

| Symptoms | Swelling, grainy discharge, weeping from sinuses, deformity.[3] |

| Causes | Madurella mycetomatis, Madurella grisea, , Curvularia lunata, Scedosporium apiospermum, , Acremonium species and Fusarium species[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Microscopy, biopsy, culture,[3] medical imaging, ELISA, immunodiffusion, PCR with DNA sequencing[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Actinomycetic mycetoma[3] |

| Treatment | Surgical debridement, antifungal medicines[3] |

| Medication | Itraconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole[4] |

| Prognosis | Recurrence is common[5] |

| Frequency | Endemic in Africa, India and South America[3] |

Eumycetoma, also known as Madura foot,[1][6] is a persistent fungal infection of the skin and the tissues just under the skin, affecting most commonly the feet, although it can occur in hands and other body parts.[5] It starts as a painless wet nodule, which may be present for years before ulceration, swelling, grainy discharge and weeping from sinuses and fistulae, followed by bone deformity.[3]

Several fungi can cause eumycetoma,[5] including: Madurella mycetomatis, Madurella grisea, , Curvularia lunata, Scedosporium apiospermum, , and Acremonium and Fusarium species.[2] Diagnosis is by biopsy, visualising the fungi under the microscope and culture.[5] Medical imaging may reveal extent of bone involvement.[4] Other tests include ELISA, immunodiffusion, and PCR with DNA sequencing.[4]

Treatment includes surgical removal of affected tissue and antifungal medicines.[3] After treatment, recurrence is common.[5] Sometimes, amputation is required.[5]

The infection occurs generally in the tropics,[7] and is endemic in Africa, India and South America.[3] In 2016, the World Health Organization recognised eumycetoma as a neglected tropical disease.[7]

Signs and symptoms[]

The initial lesion is a small swelling under the skin following minor trauma.[8][9] It appears as a painless wet nodule, which may be present for years before ulceration, swelling and weeping from sinuses, followed by bone deformity.[3][7] The sinuses discharge a grainy liquid of fungal colonies.[8] These grains are usually black or white.[10] Destruction of deeper tissues, and deformity and loss of function in the affected limbs may occur in later stages.[11] It tends to occur in one foot.[10] Mycetoma due to bacteria has similar clinical features.[12]

Causes[]

Eumycetoma is a type of mycetoma caused by fungi. Mycetoma caused by bacteria from the phylum Actinomycetes is different.[8][9] Both have similar clinical features.[12]

The most common fungi causing white discharge is Pseudallescheria boydii.[10][13] Others include fungi of the genus Pseudallescheria, Acremonium and Fusarium species.[10]

Black discharge tends to be caused by species from the genera Madurella, Pyrenochaeta, Exophiala, Leptosphaeria and Curvularia.[10] The most common species are Madurella mycetomatis[10][14] and (previously called Madurella grisea).[10][15]

Mechanism[]

The disease is acquired by entry of the fungal spores from the soil through a breach in the skin produced by minor trauma like a thorn prick.[16] The disease then spreads to deeper tissues and also forms sinus tracts leading to skin surface.[9] Mature lesions are characterised by a grainy discharge from these sinuses. These discharges contain fungal colonies and are infective. Spread of infection internally through blood or lymph is uncommon.[citation needed]

Infections that produce a black discharge mainly spread subcutaneously. In the red and yellow varieties deep spread occurs early, infiltrating muscles and bones but sparing nerves and tendons, which are highly resistant to the invasion.[17]

Botryomycosis, also known as bacterial pseudomycosis, produces a similar clinical picture and is caused usually by Staphylococcus aureus.[18] Other bacteria may also cause botryomycosis.[19]

Diagnosis[]

Diagnosis is by biopsy, visualising the fungi under the microscope and culture, which show characteristic fungal filaments and vesicles characteristic of the fungi.[5] Other tests include ELISA, immunodiffusion, and PCR with DNA sequencing.[4]

X rays and ultrasonography may be carried out to assess the extent of the disease. X rays findings are extremely variable. The disease is most often observed at an advanced stage that exhibits extensive destruction of all bones of the foot. Rarely, a single lesion may be seen in the tibia where the picture is identical with chronic osteomyelitis. Cytology of fine needle aspirate or pus from the lesion, and tissue biopsy may be undertaken sometimes.[8] Some publications have claimed a "dot in a circle sign" as a characteristic MRI feature for this condition (this feature has also been described on ultrasound).[11]

Differential diagnosis[]

The following clinical conditions may be considered before diagnosing a patient with mycetoma:

- Tuberculous ulcer

- Kaposi's sarcoma, a vascular tumour of skin usually seen in AIDS.

- Leprosy

- Syphilis

- Malignant neoplasm

- Tropical ulcer[17]

- Botryomycosis,[9] a skin infection usually caused by the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus.

Prevention[]

No vaccine is available. Simple hygienic precautions like wearing shoes or sandals while working in fields, and washing hands and feet at regular intervals may help prevent the disease.[citation needed]

Treatment[]

Surgery combined with itraconazole may be given for up to year where the cause is Scedosporium apiospermum or the grains are black.[4] Posaconazole is another option.[4] Voriconazole or posaconazole can be used for infections caused by Fusarium species.[4]

Ketoconazole has been used to treat eumycetoma.[20] Actinomycetes usually respond well to medical treatment, but fungal eumycetes are generally resistant and may require surgical interventions including salvage procedures as bone resection or even the more radical amputation.[21][9][11]

Epidemiology[]

The disease is more common in males aged 20-40 years who work as labourers, farmers and herders, and in travellers to tropical regions, where the condition is endemic.[4]

History[]

Madura foot or maduromycosis or maduramycosis[22] is described in ancient writings of India as Padavalmika, which, translated means Foot anthill.[9] The first modern description of Madura foot was made in 1842 from Madurai (the city after which the disease was named Madura mycosis) in India, by Gill.[9] The fungal cause of the disease was established in 1860 by Carter.[9]

Society and culture[]

In 2016, the World Health Organization recognised eumycetoma as a neglected tropical disease.[7] Traditionally occurring in regions where resources are scarce, medicines may be expensive and diagnosis is frequently made late, when more invasive treatment may be required.[7]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kutzner, Heinz; Kempf, Werner; Feit, Josef; Sangueza, Omar (2021). "2. Fungal infections". Atlas of Clinical Dermatopathology: Infectious and Parasitic Dermatoses. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell. p. 77-108. ISBN 978-1-119-64706-5. Archived from the original on 2021-06-10. Retrieved 2021-06-09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "25. Mycoses and Algal infections". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 457. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Queiroz-Telles, Flavio; Fahal, Ahmed Hassan; Falci, Diego R.; Caceres, Diego H.; Chiller, Tom; Pasqualotto, Alessandro C. (November 2017). "Neglected endemic mycoses". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 17 (11): e367–e377. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30306-7. ISSN 1474-4457. PMID 28774696. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2021-08-30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Estrada, Roberto; Chávez-López, Guadalupe; Estrada-Chávez, Guadalupe; López-Martínez, Rubén; Welsh, Oliverio (July 2012). "Eumycetoma". Clinics in Dermatology. 30 (4): 389–396. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.09.009. ISSN 1879-1131. PMID 22682186. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ^ Barlow, Gavin; Irving, Irving; moss, Peter J. (2020). "20. Infectious diseases". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 561. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Emery, Darcy; Denning, David W. (2020). "The global distribution of actinomycetoma and eumycetoma". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 14 (9): e0008397. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008397. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 7514014. PMID 32970667.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Davidson's principles and practice of medicine (20th ed.). Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. 2006. p. 373. ISBN 9780443101335.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Ananthanarayan BA, Jayaram CK, Paniker MD (2006). Textbook of Microbiology (7th ed.). Orient Longman Private Ltd. p. 618. ISBN 978-8125028086.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Bravo, Francisco G. (2020). "14. Fungal, viral and rickettsial infections". In Hoang, Mai P.; Selim, Maria Angelica (eds.). Hospital-Based Dermatopathology: An Illustrated Diagnostic Guide. Switzerland: Springer. pp. 638–664. ISBN 978-3-030-35819-8. Archived from the original on 2021-06-11. Retrieved 2021-06-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c El-Sobky, TA; Haleem, JF; Samir, S (2015). "Eumycetoma Osteomyelitis of the Calcaneus in a Child: A Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation following Total Calcanectomy". Case Reports in Pathology. 2015: 129020. doi:10.1155/2015/129020. PMC 4592886. PMID 26483983.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mycetoma | DermNet NZ". dermnetnz.org. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ "Filamentous Fungi". Archived from the original on 2012-08-01. Retrieved 2008-07-23.

- ^ Ahmed AO, Desplaces N, Leonard P, et al. (December 2003). "Molecular detection and identification of agents of eumycetoma: detailed report of two cases". J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 (12): 5813–6. doi:10.1128/JCM.41.12.5813-5816.2003. PMC 309011. PMID 14662990.

- ^ Vilela R, Duarte OM, Rosa CA, et al. (November 2004). "A case of eumycetoma due to Madurella grisea in northern Brazil" (PDF). Mycopathologia. 158 (4): 415–8. doi:10.1007/s11046-004-2844-y. PMID 15630550. S2CID 35337823.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Zijlstra, Eduard E.; Sande, Wendy W. J. van de; Welsh, Oliverio; Mahgoub, El Sheikh; Goodfellow, Michael; Fahal, Ahmed H. (1 January 2016). "Mycetoma: a unique neglected tropical disease". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 16 (1): 100–112. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00359-X. ISSN 1473-3099. PMID 26738840. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hamilton Bailey's Demonstrations of Physical Signs in Clinical Surgery ISBN 0-7506-0625-8

- ^ "Dorlands Medical Dictionary:botryomycosis". 5 September 2008. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ "Skin-nontumor Infectious disorders Botryomycosis". PathologyOutlines.com, Inc. Archived from the original on 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- ^ Capoor MR, Khanna G, Nair D, et al. (April 2007). "Eumycetoma pedis due to Exophiala jeanselmei". Indian J Med Microbiol. 25 (2): 155–7. doi:10.4103/0255-0857.32726. PMID 17582190.

- ^ Efared, B; Tahiri, L; Boubacar, MS; Atsam-Ebang, G; Hammas, N; Hinde, EF; Chbani, L (2017). "Mycetoma in a non-endemic area: a diagnostic challenge". BMC Clinical Pathology. 17: 1. doi:10.1186/s12907-017-0040-5. PMC 5288886. PMID 28167862.

- ^ "Infectious Disorders (Specific Agent) Madura foot/Mycetoma/Maduramycosis". MedTech USA, Inc. Archived from the original on 2014-03-22. Retrieved 2013-08-01.

External links[]

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Neglected tropical diseases

- Tropical diseases

- Mycosis-related cutaneous conditions

- Fungal diseases