European social model

The European social model is a concept that emerged in the discussion of economic globalization and typically contrasts the degree of employment regulation and social protection in European countries to conditions in the United States.[1][2] It is commonly cited in policy debates in the European Union, including by representatives of both labour unions[3] and employers,[4] to connote broadly "the conviction that economic progress and social progress are inseparable" and that "Competitiveness and solidarity have both been taken into account in building a successful Europe for the future'".[5]

European states do not all use a single social model, but welfare states in Europe do share several broad characteristics. These generally include an acceptance of political responsibility for levels and conditions of employment, social protections for all citizens, social inclusion, and democracy. Examples common among European countries include universal health care, free higher education, strong labor protections and regulations, and generous welfare programs in areas such as unemployment insurance, retirement pensions, and public housing. The Treaty of the European Community set out several social objectives: "promotion of employment, improved living and working conditions ... proper social protection, dialogue between management and labour, the development of human resources with a view to lasting high employment and the combating of exclusion."[6] Because different European states focus on different aspects of the model, it has been argued that there are four distinct social models in Europe: the Nordic, British, Mediterranean and the Continental.[7][8]

The general outlines of a European social model emerged during the post-war boom. Tony Judt lists a number of causes: the abandonment of protectionism, the baby boom, cheap energy, and a desire to catch up with living standards enjoyed in the United States. The European social model also enjoyed a low degree of external competition as the Soviet bloc, China and India were not yet integrated into the global economy.[9] In recent years, it has become common to question whether the European social model is sustainable in the face of low birthrates, globalisation, Europeanisation and an ageing population.[10][11]

Welfare state in Europe[]

Some of the European welfare states have been described as the most well developed and extensive.[12] A unique "European social model" is described in contrast with the social model existing in the US. Although each European country has its own singularities, four welfare or social models are identified in Europe:[13][14][15]

- The Nordic model in Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands

- The Continental (Christian democratic)[15] model in Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Luxembourg, Poland, and Slovenia[15]

- The Anglo-Saxon model in Ireland and the United Kingdom

- The Mediterranean model in Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain

Nordic model[]

As can be seen in the graph to the right, the Nordic model holds the highest level of social insurance. Its main characteristic is its universal provision nature which is based on the principle of "citizenship". Therefore, there exists a more generalised access, with lower conditionability, to the social provisions.

As regards labour market, these countries are characterised by important expenditures in active labour market policies whose aim is a rapid reinsertion of the unemployed into the labour market. These countries are also characterised by a high share of . Trade unions have a high membership and an important decision-making power which induces a low wage dispersion or more equitable income distribution.

The Nordic model is also characterised by a high tax wedge.

Continental model[]

The Continental model has some similarities with the Nordic model. Nevertheless, it has a higher share of its expenditures devoted to pensions. The model is based on the principle of "security" and a system of subsidies which are not conditioned to employability (for example in the case of France or Belgium, there exist subsidies whose only requirement is being older than 25).

As regards the labour market, active policies are less important than in the Nordic model and in spite of a low membership rate, trade-unions have important decision-making powers in collective agreements.

Another important aspect of the Continental model is the disability pensions.

Anglo-Saxon model[]

The Anglo-Saxon model features a lower level of expenditures than the previous ones. Its main particularity is its social assistance of last resort. Subsidies are directed to a higher extent to the working-age population and to a lower extent to pensions. Access to subsidies is (more) conditioned to employability (for instance, they are conditioned on having worked previously).

Active labour market policies are important. Instead, trade unions have smaller decision-making powers than in the previous models, this is one of the reasons explaining their higher income dispersion and their higher number of low-wage employments.

Mediterranean model[]

The Mediterranean model corresponds to southern European countries who developed their welfare state later than the previous ones (during the 1970s and 1980s). It is the model with the lowest share of expenditures and is strongly based on pensions and a low level of social assistance. There exists in these countries a higher segmentation of rights and status of persons receiving subsidies which has as one of its consequences a strongly conditioned access to social provisions.

The main characteristic of labour market policies is a rigid employment protection legislation and a frequent resort to early retirement policies as a means to improve employment conditions. Trade unions tend to have an important membership which again is one of the explanations behind a lower income dispersion than in the Anglo-Saxon model.

Evaluating the different social models[]

To evaluate the different social models, we follow the criteria used in Boeri (2002) and Sapir (2005) which consider that a social model should satisfy the following:

- Reduction in poverty.

- Protection against labour market risks.

- Rewards for labour participation.

Reduction in poverty[]

The graph on the right shows the reduction in inequality (as measured by the Gini index) after taking account of taxes and transfers, that is, to which extent does each social model reduce poverty without taking into account the reduction in poverty provoked by taxes and transfers. The level of social expenditures is an indicator of the capacity of each model to reduce poverty: a bigger share of expenditures is in general associated to a higher reduction in poverty. Nevertheless, another aspect that should be taken into account is the efficiency in this poverty reduction. By this is meant that with a lower share of expenditures a higher reduction in poverty may be obtained.[16]

In this case, the graph on the right shows that the Anglosaxon and Nordic models are more efficient than the Continental or Mediterranean ones. The Continental model appears to be the least efficient. Given its high level of social expenditures, one would expect a higher poverty reduction than that attained by this model. Remark how the Anglosaxon model is found above the average line drawn whereas the Continental is found below that line.

Protection against labour market risks[]

Protection against labour market risks is generally assured by two means:

- Regulation of the labour market by means of employment protection legislation which basically increases firing costs and for the employers. This is generally referred to as providing "employment" protection.

- Unemployment benefits which are commonly financed with taxes or to the employees and employers. This is generally referred to as providing protection to the "worker" as opposed to "employment".

As can be seen in the graph, there is a clear trade-off between these two types of labour market instruments (remark the clear negative slope between both). Once again different European countries have chosen a different position in their use of these two mechanisms of labour market protection. These differences can be summarised as follows:

- The Mediterranean countries have chosen a higher "employment" protection while a very low share of their unemployed workers receives unemployment benefits.

- The Nordic countries have chosen to protect to a lesser extent "employment" and instead, an important share of their unemployed workers receives benefits.

- The continental countries have a higher level of both mechanisms than the European average, although by a small margin.

- The Anglo-Saxon countries base their protection on unemployment benefits and a low level of employment protection.

Evaluating the different choices is a hard task. In general there exists consensus among economists on the fact that employment protection generates inefficiencies inside firms. Instead, there is no such consensus as regards the question of whether employment protection generates a higher level of unemployment.

Rewards for labour participation[]

Sapir (2005) and Boeri (2002) propose looking at the employment-to-population ratio as the best way to analyse the incentives and rewards for employment in each social model. The Lisbon Strategy initiated in 2001 established that the members of the EU should attain a 70% employment rate by 2010.

In this case, the graph shows that the countries in the Nordic and Anglosaxon model are the ones with the highest employment rate whereas the Continental and Mediterranean countries have not attained the Lisbon Strategy target.

Conclusion[]

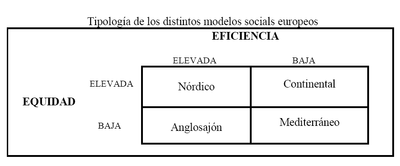

Sapir (2005) proposes as a general mean to evaluate the different social models, the following two criteria:

- Efficiency, that is, whether the model provides the incentives so as to achieve the largest number possible of employed persons, that is, the highest employment rate.

- Equity, that is, whether the social model achieves a relatively low poverty risk.

As can be seen in the graph, according to these two criteria, the best performance is achieved by the Nordic model. The Continental model should improve its efficiency whereas the Anglosaxon model its equity. The Mediterranean model under-performs in both criteria.

Some economists consider that between the Continental model and the Anglo-Saxon, the latter should be preferred given its better results in employment, which make it more sustainable in the long term, whereas the equity level depends on the preferences of each country (Sapir, 2005). Other economists argue that the Continental model cannot be considered worse than the Anglosaxon given that it is also the result of the preferences of those countries that support it (Fitoussi et al., 2000; Blanchard, 2004). This last argument can be used to justify any policy.

See also[]

- Disability pension

- Social insurance

- Social protection

- Social security

- Social welfare provision

- Welfare state

Location-specific:

- Tax rates of Europe

- US welfare state

References[]

- ^ Alber, Jens; Gilbert, Neil (2010). United in Diversity?: Comparing Social Models in Europe and America. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Onlin. ISBN 9780195376630. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ McDowell, Manfred (1995). "NAFTA and the EC Social Dimension". Labour Studies Journal. 20 (1). Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ ETUC. "The European Social Model". etuc.org. European Trade Union Congress. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ European Social and Economic Committee, Employers Group. "The European Social Model: Can we still afford it in this globalised world?" (PDF). eesc.europa.eu/. European Social and Economic Committee. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ European Observatory of Working Life, EurWORK. "European social model". eurofound.europa.eu. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "The European Social Model". European Trade Union Confederation. 21 March 2007. Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ Sapir, André. 2005. Globalisation and the Reform of European Social Models. Bruegel. http://www.bruegel.org/1425[permanent dead link].

- ^ Barr, N. (2004), Economics of the welfare state. New York: Oxford University Press (USA).

- ^ Charlemagne (11 December 2008). "The Economist". The left's resignation note. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ Martin De Vlieghere & Paul Vreymans (23 March 2006). "Europe's Ailing Social Model: Facts & Fairy-Tales". The Brussels Journal. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ "Remarks by Governor Liikanen: "A European Social Model: an Asset or a Liability?"". Budapest: The World Political Forum. 27 November 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- ^ See article Archived 24 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sapir, A. (2005): Globalisation and the Reform of European Social Models, Bruegel, Bruselas. Accessible por internet en [1]

- ^ Boeri, T. (2002): Let Social Policy Models Compete and Europe Will Win, conference in the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 11–12 April 2002.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Christian Aspalter, Kim Jinsoo, Park Sojeung. Analysing the Welfare State in Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovenia: An Ideal-Typical Perspective. Published on 10 March 2009. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2009.00654.x

- ^ Prokurat, Sergiusz (2010), European Social Model and East Asian Economic Model – different approach to productivity and competition in economy (PDF), Wrocław: Asia – Europe. Partnership or Rivalry?”, pp. 35–47, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2016, retrieved 4 August 2016

Bibliography[]

- Blanchard, O. (2004): The Economic Future of Europe. NBER Economic Papers.

- Boeri, T. (2002): Let Social Policy Models Compete and Europe Will Win, conference in the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 11–12 April 2002.

- Sapir, A. (2005): Globalisation and the Reform of European Social Models, Bruegel, Brussels. Downloadable here.

- Fitoussi J.P. and O. Passet (2000): Reformes structurelles et politiques macroéconomiques: les enseignements des «modèles» de pays, en Reduction du chômage : les réussites en Europe. Rapport du Conseil d'Analyse Economique, n.23, Paris, La documentation Française, pp. 11–96.

- Busch, Klaus: The Corridor Model – Relaunched, edited by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, International Policy Analysis, Berlin 2011.

- Economy of Europe

- European society

- Eurozone crisis

- Political-economic models

- Social systems

- Welfare in Europe

- Welfare state