Faisal of Saudi Arabia

| Faisal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques | |||||

| |||||

| King of Saudi Arabia | |||||

| Reign | 2 November 1964 – 25 March 1975 | ||||

| Bay'ah | 2 November 1964 | ||||

| Predecessor | Saud bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Successor | Khalid bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Regent of Saudi Arabia | |||||

| Tenure | 4 March 1964 – 2 November 1964 | ||||

Monarch | Saud bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Prime Minister of Saudi Arabia | |||||

| Tenure | 16 August 1954 – 21 December 1960 | ||||

| Predecessor | Saud bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Successor | Saud bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Tenure | 1962 – 25 March 1975 | ||||

| Predecessor | Saud bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Successor | Khalid bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia | |||||

| Tenure | 9 November 1953 – 2 November 1964 | ||||

Monarch | Saud bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Predecessor | Saud bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Successor | Khalid bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |||||

| Tenure | 19 December 1930 – 22 December 1960 | ||||

Monarch | Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Saud bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Predecessor | Office established | ||||

| Successor | Ibrahim bin Abdullah Al Suwaiyel | ||||

| Tenure | 16 March 1962 – 25 March 1975 | ||||

Monarch | Saud bin Abdulaziz Himself | ||||

| Predecessor | Ibrahim bin Abdullah Al Suwaiyel | ||||

| Successor | Saud Al Faisal | ||||

| Viceroy of Hejaz | |||||

| Tenure | 9 February 1926 – 22 September 1932 | ||||

Monarch | Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman | ||||

| Successor | Khalid bin Abdulaziz | ||||

| Born | 14 April 1906 Riyadh, Emirate of Riyadh | ||||

| Died | 25 March 1975 (aged 68) Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | ||||

| Burial | 26 March 1975 Al-Oud cemetery, Riyadh | ||||

| Spouses | List

| ||||

| Issue Among others... | List

| ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Saud | ||||

| Father | Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia | ||||

| Mother | Tarfa bint Abdullah Al Sheikh | ||||

| Signature | |||||

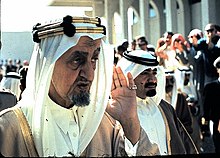

Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (Arabic: فيصل بن عبدالعزيز آل سعود Fayṣal ibn ʿAbd al ʿAzīz Āl Suʿūd, Najdi Arabic pronunciation: [fajsˤal ben ˈʕabd alʕaˈziːz ʔaːl saˈʕuːd]; 14 April 1906 – 25 March 1975) was a Saudi Arabian statesman and diplomat who was the King of Saudi Arabia from 2 November 1964 until his assassination in 1975. He was the third son of King Abdulaziz, the founder of modern Saudi Arabia,[note 1] and the second of Abdulaziz's six sons who were kings.[note 2]

Faisal was the son of Abdulaziz and Tarfa bint Abdullah Al Sheikh. His father was still reigning as Emir of Nejd at the time of Faisal's birth, and his mother was from the Al ash-Sheikh family which has produced many prominent Saudi religious leaders. Faisal emerged as an influential royal politician during the reigns of his father, Abdulaziz, and his half-brother Saud. He was the Saudi foreign minister from 1930 and prime minister from 1954 until his death, except for a two-year break (1960–1962) in both positions. Faisal was crown prince of Saudi Arabia after Saud's accession in 1953, and in that position he outlawed slavery in Saudi Arabia. He persuaded King Saud to abdicate in his favour in 1964 with the help of other members of the royal family and his first cousin, Grand Mufti Muhammad ibn Ibrahim Al ash-Sheikh.[1]

Faisal implemented a policy of modernization and reform. His main foreign policy themes were pan-Islamism, anti-communism,[2][note 3] and pro-Palestinianism.[3] He attempted to limit the power of Islamic religious officials. Protesting against support that Israel received from the West, he led the oil embargo which caused the 1973 oil crisis. Faisal successfully stabilized the kingdom's bureaucracy, and his reign had significant popularity among Saudi Arabians despite his reforms facing some controversy. In 1975, he was assassinated by his nephew Faisal bin Musaid. King Faisal was succeeded by his half-brother Khalid bin Abdulaziz.

Early life and education

Faisal bin Abdulaziz was born in Riyadh on 14 April 1906.[4][5] He was the third son of Abdulaziz, then Emir of Nejd; Faisal was the first of his father's sons who was born in Riyadh.[6][7] His mother was Tarfa bint Abdullah Al Sheikh,[8] whom Abdulaziz had married in 1902 after capturing Riyadh. Tarfa was a descendant of the religious leader Muhammad bin Abdul Wahhab.[9] Faisal's grandfather Abdullah bin Abdullatif Al Sheikh was one of Abdulaziz's principal religious teachers and advisers.[10][11] Faisal had an older full sister, Noura, who married her cousin Khalid bin Muhammad, a son of King Abdulaziz's half-brother Muhammad bin Abdul Rahman.[12][note 4]

Tarfa bint Abdullah died in 1906 when Faisal was six months old.[10] He then began to live with his maternal grandparents, Abdullah bin Abdullatif and Haya bint Abdul Rahman Al Muqbel,[13] and Abdullah educated his grandson.[10] According to Helen Chapin Metz, Faisal, and most of his generation, was raised in an atmosphere in which courage was extremely valued and reinforced.[14] From 1916 he was tutored by Hafiz Wahba who later served in various governmental posts.[15]

In 1919 the British government invited Abdulaziz to visit London.[16] He could not go, but he assigned his eldest son Prince Turki as his envoy.[16] However, Prince Turki died due to Spanish flu before the visit.[16] Therefore, Prince Faisal was sent to London instead, making him the first ever Saudi Arabian royal to visit England.[16] His visit lasted for five months, and he met with British officials.[17] During the same period, he also visited France, again being the first Saudi Arabian royal to pay an official visit there.[18]

Early political experience

As one of Abdulaziz's eldest sons, Prince Faisal was given numerous responsibilities to consolidate control over Arabia. After the capture of Hail and initial control over Asir in 1922, he was sent to these provinces with nearly six thousand fighters. He achieved complete control over Asir at the end of the year.[19] Prince Faisal was appointed viceroy of Hejaz on 9 February 1926 following his father's takeover of the region.[20][21][22] He often consulted with local leaders during his tenure.[23] In addition, Prince Faisal was the president of the consultative assembly and the minister of interior.[24]

In December 1931 following the announcement of the constitution of the council of deputies (Majlis al Wukala) he became the president of the four-member council and minister of foreign affairs, and continued to hold his previous titles, viceroy of Hejaz, the president of the consultative assembly and the minister of interior.[24] He would continue to oversee Saudi foreign policy until his death—even as king, with only a two-year break[25] between 1960 and 1962.[21]

Faisal visited several countries in this period, including Iran in May 1932,[26] Poland in 1932 and Russia (as part of the USSR) in 1933.[27][28] On 8 July 1932 Faisal visited Turkey and met with Kemal Atatürk, founder of modern Turkey.[29]

He commanded a campaign during the Saudi–Yemeni War in 1934, resulting in a Saudi victory.[21] He and his half-brother Khalid visited the US in October 1943 following the invitation of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[30] This is one of the early contacts between Saudi Arabia and the USA.[30]

After he became foreign minister, Prince Faisal was recognized for his support for the Palestinian cause. His involvement with the Palestinian cause began in 1938, when he represented his father in the London Conference on the Palestine issue, where he delivered an important address opposing the partition plan. He wrote a message to the Saudi people in 1948 in which he discussed the Palestinian struggle and the suffering of the Palestinian people.[31]

As King Abdulaziz neared the end of his life, he favored Prince Faisal as a possible successor over his eldest living son, Crown Prince Saud, due to Faisal's extensive knowledge, as well as his years of experience. Since Faisal was a child, Abdulaziz recognized him as the most brilliant of his sons and often tasked him with responsibilities in war and diplomacy. In addition, Faisal was known to embrace a simple Bedouin lifestyle. "I only wish I had three Faisals", King Abdulaziz once said when discussing who would succeed him.[32] However, King Abdulaziz made the decision to keep Saud as crown prince in the fear that otherwise would lead to decreased stability.[33]

Crown prince and prime minister

King Abdulaziz died on 9 November 1953, and Prince Faisal was at his side.[5][34][35] Prince Faisal's elder half-brother, Saud, became king. Faisal was then appointed crown prince. On 16 August 1954 he was made prime minister.[36]

King Saud embarked on a spending program that included the construction of a massive royal residence on the outskirts of the capital, Riyadh. He also faced pressure from neighboring Egypt, where Gamal Abdel Nasser had overthrown the monarchy in 1952. Nasser was able to cultivate a group of dissident princes (known as the Free Princes) led by Prince Talal bin Abdulaziz, who defected to Egypt. Fearing that King Saud's financial policies were bringing the state to the brink of collapse, and that his handling of foreign affairs was inept, senior members of the royal family and the ulema (religious leadership) pressured Saud into appointing Faisal to the position of prime minister in 1958, giving Faisal wide executive powers.[37]

A power struggle ensued between King Saud and Crown Prince Faisal, and on 18 December 1960, Crown Prince Faisal resigned as prime minister in protest, arguing that King Saud was frustrating his financial reforms. King Saud took back his executive powers and, having induced Prince Talal to return from Egypt, appointed him as minister of finance in July 1958.[38][39] In 1962, however, Crown Prince Faisal rallied enough support within the royal family to install himself as prime minister for a second time.[37] Less than a month before this event Crown Prince Faisal and US President John F. Kennedy held a secret meeting in Washington, D.C. on 4 October 1962.[40][41] The same year, Crown Prince Faisal announced the Ten Point Program, which outlined Saudi Arabia's path to becoming an industrialized nation by implementing economic, financial, political, and legal principles. Among the highlights were:

- Issuing a basic system of governance derived from Islamic Sharia and developing the system of governance and the Council of Ministers.

- Establishing a system for the provinces, clarifying the method of local government, in the various regions of the Kingdom.

- Establishing a system for the independence of the judiciary, under the control of a Supreme Judicial Council, and establishing the Ministry of Justice.

- Establishing a Supreme Council for issuing fatwas, comprising twenty members of jurists.

- Improving the social level of the Saudi people, through free medical treatment, free education, and the exemption of many foodstuffs from customs duties. In addition, a social security system and a system to protect workers from unemployment were established.

- Establishing a program for economic recovery, strengthening the financial position of the Kingdom, developing a program to raise the standard of living of citizens, establishing a road network linking parts of the Kingdom and its cities, providing water sources for drinking and agriculture, and ensuring the protection of light and heavy national industries. This includes allocating all the additional sums that the government will receive from Aramco for its rights claimed by the companies for the past years, and harnessing them to serve development projects.

- Continuing to develop girls' education as well as the advancement of women.

- The liberation of slaves and the abolition of slavery, once and for all in Saudi Arabia.[42][20]

Crown Prince Faisal founded Economic Development Committee in 1958.[43] He was instrumental in the establishment of the Islamic University of Madinah in 1961. In 1962 he helped found the Muslim World League, a worldwide charity to which the Saudi royal family has reportedly since donated more than a billion dollars.[44] In 1963 he established the country's first television station, though actual broadcasts would not begin for another two years.[45]

Struggle with King Saud

The struggle with King Saud continued in the background during this time. Taking advantage of the king's absence from the country for medical reasons in early 1963, Faisal began amassing more power for himself. He removed many of Saud's loyalists from their posts and appointed like-minded princes in key military and security positions,[46][47] such as his half-brother Prince Abdullah, to whom he gave command of the National Guard in 1962. Upon King Saud's return, Crown Prince Faisal demanded that he be made regent and that King Saud be reduced to a purely ceremonial role. In this, he had the crucial backing of the ulema (elite Islamic scholars), including a fatwā (edict) issued by the grand mufti of Saudi Arabia, a relative of Crown Prince Faisal on his mother's side, calling on King Saud to accede to his brother's demands.[46]

King Saud refused, however, and made a last-ditch attempt to retake executive powers, leading Crown Prince Faisal to order the National Guard to surround King Saud's palace. His loyalists outnumbered and outgunned, King Saud relented, and on 4 March 1964, Crown Prince Faisal was appointed regent. A meeting of the elders of the royal family and the ulema was convened later that year, and a second fatwā was decreed by the grand mufti, calling on King Saud to abdicate the throne in favor of his brother. The royal family supported the fatwā and immediately informed King Saud of their decision. King Saud, by now shorn of all his powers, agreed, and Faisal was proclaimed king on 2 November 1964.[37][47] Saud then went into exile, finding refuge in Egypt before eventually settling in Greece.[48]

King of Saudi Arabia

In a speech shortly after he came to power on 2 November 1964, Faisal said:

I beg of you, brothers, to look upon me as both brother and servant. 'Majesty' is reserved to God alone and 'the throne' is the throne of the Heavens and Earth.[49]

One of the earliest actions Faisal took as king was to establish a council to deal with future succession issues.[50] The members were two of his uncles, Prince Abdullah and Prince Musaid, and five of his half-brothers, Crown Prince Khalid, Prince Fahd, Prince Abdullah, Prince Sultan and Prince Nawwaf.[50] In 1967 King Faisal established the post of second prime minister and appointed Prince Fahd to this post.[41] The reason for this newly established body was Crown Prince Khalid's request and suggestion.[51] King Faisal's most senior adviser during his reign was Rashad Pharaon, his father's private physician.[52] Another adviser was Mohammad ibn Ibrahim Al Sheikh, who was influential in shaping the king's political role in the Arab world.[53]

Modernization

Early in his rule, King Faisal issued an edict that all Saudi princes had to school their children inside the country, rather than sending them abroad; this had the effect of making it popular for upper-class families to bring their sons back to study in the Kingdom.[54] King Faisal also introduced the country's current system of administrative regions, and laid the foundations for a modern welfare system. In 1970 he established the Ministry of Justice and inaugurated the country's first "five-year plan" for economic development.[55]

One of his modernization attempts was the new laws on media, publishing, and archiving and bilateral cultural cooperation protocols with foreign and corporate archives that kept records about mid-twentieth century Arabia.[40] Television broadcasts officially began in 1965. The same year a nephew of Faisal attacked the newly established headquarters of Saudi television but was killed by security personnel. The attacker was the brother of Faisal's future assassin, and the incident is the most widely accepted motive for the murder.[56] Although there was some discontent with the social changes he carried out, the Arab world grew to respect Faisal as a result of his policies modernizing Saudi Arabia, his management of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, his reputation as a staunch opponent of Zionism, and the country's fast-rising financial strength.[57]

Steps against coups d'état

The 1950s and 1960s saw numerous coups d'état in the region. Muammar Gaddafi's coup that overthrew the monarchy in oil-rich Libya in 1969 was especially threatening for Saudi Arabia due to the similarity between the two sparsely-populated desert countries.[58] As a result, King Faisal undertook to build a sophisticated security apparatus and cracked down firmly on dissent. As in all affairs, King Faisal justified these policies in Islamic terms. Early in his reign, when faced with demands for a written constitution for the country, King Faisal responded that "our constitution is the Quran".[59] In the summer of 1969 King Faisal ordered the arrest of hundreds of military officers, including some generals,[60] alleging that a military coup d'état was being planned. The coup was planned primarily by air force officers and aimed at overthrowing the monarchy and founding a Nasserist regime in the country.[61] The arrests were possibly based on a tip from American intelligence.[58]

Religious inclusiveness

King Faisal seemed to hold the pluralist view, favouring limited, cautious accommodation of popular demands for inclusive reform, and made repeated attempts to broaden political representation, harking back to his temporarily successful national integration policy from 1965 to 1975. King Faisal acknowledged his country's religious and cultural diversity, which includes the predominantly Shia Al Ahsa in the east; the Asir in the southwest, with tribal affinities to Yemen, especially among the Ismaili tribes of Najran and Jizan; and the Kingdom of the Hejaz, with its capital Mecca. He included non-Wahhabi, cosmopolitan Sunni Hejazis from Mecca and Jeddah in the Saudi government.[62] It was said that he would not take any decision regarding Mecca without seeking the advice of Sunni (Sufi) scholar al-Sayyid 'Alawi ibn 'Abbas al-Maliki al-Hasani, the father of Muhammad ibn 'Alawi al-Maliki.[63] Similarly in 1962, in promoting a broader, non-sectarian form of pan-Islamism, King Faisal launched the Muslim World League where the Tijani Sufi scholar Ibrahim Niass was invited.[64] Furthermore, he countered the outlook of certain prior Saudi rulers in declaring to the Saudi state clergy that, "All Muslims, from Egypt, India etc. are your brothers,"[65] However Mai Yamani argued that after his reign, discrimination based on sect, tribe, region, and gender became the order of the day and has remained as such until today.[62]

The role and authority of the state clergy declined after the rise of King Faisal even though they had helped bring him to the throne in 1964. Despite his piety and biological relationship through his mother to the Al as Shaykh family, and his support for the pan-Islamic movement in his struggle against pan-Arabism, he decreased the ulema's power and influence.[66] Unlike his successor King Khalid, King Faisal attempted to prevent radical clerics from controlling religious institutions such as the Council of Senior Ulema, the highest religious institution in Saudi Arabia, or taking religious offices such as Grand Mufti, responsible for preserving Islamic law. But his advisers warned that, once religious zealots had been motivated, disastrous effects would result.[44]

Due to his status as a pious Muslim, Faisal was able to implement careful social reforms such as female education. Despite this, religious conservatives staged large protests. By holding talks with the conservatives, he was able to persuade them of the importance of progress in the coming years by using their own logic.[66][67][68]

Corruption in the royal family was taken very seriously by religious figures in the Islamic theological colleges. They challenged some of the accepted theological interpretations adopted by the Saudi regime. One such influential figure was Shaykh Abdulaziz bin Baz, then rector of the Al Medina college of theology. King Faisal would not tolerate his criticism and had him removed from his position. However, his teachings had already radicalized some of his students one of which was Juhayman al-Otaybi.[69]

Abolition of slavery

Slavery did not vanish in Saudi Arabia until King Faisal issued a decree for its total abolition in 1962. BBC presenter Peter Hobday stated that about 1,682 slaves were freed at that time, at a cost to the government of $2,000 each.[69] The political analyst Bruce Riedel argued that the US began to raise the issue of slavery after the meeting between King Abdulaziz and US president Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945 and that John F. Kennedy finally persuaded the House of Saud to abolish slavery in 1962.[70]

Foreign relations

As king, Faisal employed Islam as one of Saudi Arabia's foreign policy tools which differentiated him from King Abdulaziz and King Saud.[71] However, he continued the close alliance with the United States begun by King Abdulaziz, and relied on the US heavily for arming and training his armed forces. King Faisal was anti-communist. He refused any political ties with the Soviet Union and other Communist bloc countries, professing to see a complete incompatibility between communism and Islam.[72] His first official visit as king to the US was in June 1966.[30]

Faisal is said to have reminded the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, in a correspondence that he was not "the Shah of France" and that he should keep in mind that Iran was a majority Muslim country. This was in response to comments from Mohammad Reza asking Faisal to modernise Saudi Arabia, allowing women to wear miniskirts and permitting the disco among other things. Otherwise, the Shah felt, he could not guarantee that the King would stay on the throne.[73]

Six-Day War

During the Six-Day War, King Faisal ordered the Saudi Arabian Armed Forces to be on alert, canceling all vacations and mobilizing forces in the Kingdom's north. Following that, orders were issued for a force of 20,000 Saudi soldiers to travel to Jordan to participate alongside the Arab forces. After the war, he directed that a Saudi force be stationed inside Jordanian territory to provide support and assistance as needed for ten years.[74][75] Furthermore, at the Khartoum Conference, Saudi Arabia, Libya, and Kuwait agreed to establish a fund worth $378 million to be distributed among countries affected by the June 1967 War. Saudi Arabia would contribute $140 million.[76]

Prince Amr bin Mohammed Al-Faisal said “I am told by my relatives, my other relatives, after 1967 and the fall of Jerusalem to the Israelis, that was a turning point in his life. He never smiled again, according to them. I didn't see him smile much, and he became very quiet and contemplative, and mostly he would spend his time listening rather than speaking himself.”[77]

Arson attack on Al-Aqsa Mosque

Between 23 and 25 September 1969, King Faisal convened a conference in Rabat, Morocco, to discuss the arson attack on the Al Aqsa Mosque that had occurred a month earlier. The leaders of 25 Muslim states attended and the conference called for Israel to give up territory conquered in 1967. The conference also set up the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and pledged its support for the Palestinians.[78]

Yom Kippur War

Following the death of Nasser in 1970, King Faisal drew closer to Egypt's new president, Anwar Sadat, who himself was planning a break with the Soviet Union and a move towards the pro-American camp.

During the 1973 Arab–Israeli War launched by Sadat, King Faisal withdrew Saudi oil from world markets and was the primary force behind the 1973 oil crisis, in protest over Western support for Israel during the conflict. The embargo was initially imposed on Canada, Japan, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States, but it was later extended to Portugal, Rhodesia, and South Africa.[79] The price of oil had risen about 300 percent by the conclusion of the embargo in March 1974,[80] from US$3 per barrel ($19/m3) to nearly $12 per barrel ($75/m3) globally; US prices were much higher. The embargo triggered an oil crisis, or "shock," with numerous short- and long-term implications for world politics and the economy. This was regarded as the defining act of King Faisal's career, and gained him lasting prestige among many Arabs and Muslims worldwide.

In 1974 he was named Time magazine's Man of the Year, and the financial windfall generated by the crisis fueled the economic boom that occurred in Saudi Arabia after his death. The new oil revenue also allowed Faisal to greatly increase the aid and subsidies begun following the 1967 Six-Day War[3] to Egypt, Syria, and the Palestine Liberation Organization.[81]

It is a commonly-held belief in Saudi Arabia, and the wider Arab world, that King Faisal's oil embargo was the real cause of his assassination, via a Western conspiracy.[82][83]

Personal life

King Faisal married many times concurrently.[13] His spouses were from powerful families: Al Kabir, Al Sudairi, Al Jiluwi and Al Thunayan.[84] His wives were:

- Sultana bint Ahmed Al Sudairi, the mother of his eldest son Prince Abdullah, whom Faisal fathered when he was between 15 and 17. Sultana was from the Sudairi family and the younger sister of Hassa bint Ahmed, the mother of the Sudairi brothers.[48]

- Iffat Al-Thunayan (1916–2000), who was born and raised in Turkey. Her ancestors were part of the Al Thunayan branch of the Al Saud family.[85] They first met in Istanbul around 1932 while he was in Turkey for an official visit.[17][86] They had nine children,[85] including Prince Mohammed, Prince Saud, and Prince Turki.[87] Iffat was credited with being the influence behind many of her husband's reforms, particularly with regard to women.[88][89] Faisal also raised Iffat's younger half-brother, Kamal Adham.[90] King Faisal later appointed Kamal as the first president of the Saudi intelligence agency, Al Mukhabarat Al A'amah.[91] He was also an advisor to his royal brother-in-law.[92]

- Al Jawhara bint Saud Al Kabir, the daughter of his aunt Noura bint Abdul Rahman and Saud Al Kabir bin Abdulaziz Al Saud.[93] They married in October 1935. With Al Jawhara, Faisal had one daughter, Mashail (died October 2011).[13]

- Haya bint Turki bin Abdulaziz Al Turki, the mother of Princess Noura, Prince Saad and Prince Khalid.[94] She was a member of the Al Jiluwi clan.[8][95]

- Hessa bint Muhammad bin Abdullah Al Muhanna Aba Al Khail, the mother of Princess Al Anoud (died June 2011) and Princess Al Jawhara (died April 2014).[13]

- Munira bint Suhaim bin Hitimi Al Thunayan Al Mahasher, the mother of Princess Hessa (died in December 2020).[96]

- Fatima bint Abdulaziz bin Mushait Al Shahrani, the mother of Princess Munira (died young).[13]

King Faisal's children were well educated and had prominent roles in Saudi society and government. His daughters were educated abroad and they went on to graduate from a variety of schools and universities around the world.[97][98] His sons were likewise educated abroad.[99] Comparatively, only six of the 108 children of his half-brother and predecessor, King Saud, graduated from high school.[97][98] King Faisal's son Prince Turki received formal education at prestigious schools in New Jersey, and he later attended Georgetown University,[100] while Prince Saud was an alumnus of Princeton University. King Faisal's sons held important positions in the Saudi government. His eldest son, Prince Abdullah, held governmental positions for a while. Prince Khalid was the governor of Asir Province in southwestern Saudi Arabia for more than three decades before becoming governor of Makkah Province in 2007. Prince Saud was the Saudi foreign minister between 1975 and 2015. Prince Turki served as head of Saudi Intelligence, ambassador to the United Kingdom, and later ambassador to the United States.[101] Prince Abdul Rahman who was a graduate of Sandhurst Military Academy died in March 2014. Prince Mohammed who died in 2017 was a businessman. Prince Saad died in April 2017.[102] King Faisal's daughters also held important roles in Saudi society. From 2013 to 2016, his daughter Princess Sara served in the Shura Council.[103][104] She is also a prominent activist for women's education and other social issues in Saudi Arabia, and so are her sisters Princess Lolowah, Princess Latifa, and Princess Haifa.[105][20][106]

King Faisal's daughter Haifa is married to Prince Bandar, son of the king's half-brother Prince Sultan by a concubine. The marriage forced Prince Sultan to recognize Bandar as a legitimate prince. Another daughter of King Faisal, Lolowah, is a prominent activist for women's education in Saudi Arabia. In 1962 his daughter Sara founded one of the first charitable organizations, Al Nahda, which won the first Chaillot prize for human rights organisations in the Gulf in 2009.[107] Her spouse was Prince Muhammed, one of King Saud's sons. One of his daughters, Princess Mishail, died at the age of 72 in October 2011.[108] His granddaughter Reem bint Mohammed is a photographer and gallery owner based in Jeddah.[109][110]

Unlike most of his half-brothers, King Faisal spoke fluent English and French. However, he preferred to speak in Arabic. When his translators made errors, Faisal would correct them.[111]

Personality and pastimes

King Faisal was known for his integrity, extreme humility, kindness, and tact with everyone. As a result, he was ascetic, avoiding displays of extravagance and luxury. He had many hobbies, some of which were falconry, hunting, literature, reading, and poetry. He was also a big admirer of the yearly Najdi festivals and celebrations.[112] Faisal chose to work long hours and set aside some of his interests after assuming power and becoming preoccupied with state affairs.[113]

| Family tree of King Faisal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Assassination and aftermath

On 25 March 1975, King Faisal was shot point-blank and killed by Faisal bin Musaid, son of his half-brother Musaid bin Abdulaziz. Prince Faisal bin Musaid had just come back from the United States. The murder occurred at a majlis (literally 'a place for sitting'), an event where the king or leader opens up his residence to the citizens to enter and petition him.[115]

In the waiting room, Prince Faisal talked to Kuwaiti representatives who were also waiting to meet the king. When the prince went to embrace him, King Faisal leaned to kiss his nephew in accordance with Saudi custom. At that instant, Prince Faisal bin Musaid took out a pistol and shot him. The first shot hit King Faisal's chin and the second one went through his ear. A bodyguard hit Prince Faisal with a sheathed sword. Oil minister Zaki Yamani yelled repeatedly not to kill the prince.[116]

King Faisal was quickly taken to a hospital. He was still alive as doctors massaged his heart and gave him a blood transfusion. Their efforts were unsuccessful, and King Faisal died shortly afterward. Both before and after the attack the assassin was reported to be calm. Following the killing, Riyadh had three days of mourning during which all government activities were suspended.[116] The funeral service for King Faisal was performed in 'Id mosque in Riyadh,[117] and he was buried in Al Oud cemetery on 26 March 1975.[118][119] During the funeral, the newly ascended King Khalid wept over his murdered brother's body.[120]

One theory for the murder of King Faisal was avenging the death of Prince Khalid bin Musaid, the brother of Prince Faisal bin Musaid. King Faisal instituted secular reforms that led to the installation of television, which provoked violent protests. Prince Khalid led an attack on a television station in 1966, and he was shot dead by a policeman.[121]

According to claims by King Faisal's family and friends, Prince Faisal bin Musaid had informed his mother Watfa bint Muhammad Al Rashid of his assassination plans. Wafta then informed King Faisal, who said "if it is Allah's will, then it would happen." In a documentary entitled "Faisal, Legacy of a King", Faisal's grandson Amr bin Mohammed bin Faisal claims that the king had distanced himself from the world days before his death. Zaki Yamani claimed that King Faisal told his own relatives and friends about a dream he had in which his father, the late King Abdulaziz, was traveling in a car and asked him to get in. Yamani went on to say that if a dead person takes a living person in a dream, the living person will most likely die within a short amount of time according to Islamic beliefs.[122][123]

Prince Faisal bin Musaid was captured directly after the attack. He was at first officially declared insane, but following the trial a panel of Saudi medical experts decided that he was sane when he shot the king. The nation's high religious court convicted him of regicide and sentenced him to execution. He was publicly beheaded in Deera Square in Riyadh.[116]

Memorials and legacy

After his death, the King Faisal Foundation, a philanthropic organisation, was established in King Faisal's honour.[124] King Faisal was eulogized by lyricist Robert Hunter in the title track of the Grateful Dead's 1975 album Blues for Allah.[125]

Following the reign of King Faisal Gerald de Gaury published a biography of him entitled Faisal: King of Saudi Arabia.[126] In 2013 Russian Arabist Alexei Vassiliev published another biography, King Faisal of Saudi Arabia: Personality, Faith and Times.[2] A movie directed by Agustí Villaronga in 2019 entitled Born a King is about the visit of King Faisal to London in 1919 when he was thirteen years old.[127]

In October 1976 King Khalid initiated the construction of Faisal Mosque in Islamabad, Pakistan.[128] Lyallpur, the third largest city of Pakistan, was renamed Faisalabad (literally, "City of Faisal") in 1979 in his honor.[129][130] One of the two major Pakistan Air Force bases in Pakistan's Sindh province's largest city, Karachi, is named "PAF Base Faisal" in honour of King Faisal.[130][131]

His words

Generalized quotes

"The livers are broken, and the wings are torn apart when we hear or see our brothers in religion, in the homeland, and in blood, their sanctities are violated, they are displaced and abused daily, not for something they committed, nor for the aggression they attacked, but for the love of control and aggression and to commit injustice." –King Faisal bin Abdulaziz[132]

- "The Islamic call, when it emerged from these places and spread its light to all parts of the earth, was a good call that calls for peace, calls for truth, calls for justice and calls for equality, and this is what our noble Sharia achieves, and this is what we must follow and adhere to."[133]

- "We are not the ones who say, 'We will work, but we are used to God's power to say: We have worked."[134]

- "Arm yourselves with science"[134]

- "If I were not a king, I would be a teacher."[134]

- "Our youth education is based on three pillars: belief, science and work."[134]

- "We want this Kingdom to be a beacon of light for humanity, now and fifty years from now."[134]

Israel and Palestine

- On March 28, 1965, Saudi Arabia's national radio broadcast a declaration by King Faisal about his country's willingness to use oil as a weapon against Israel. He said, "We consider the issue of Palestine our cause and the first Arab cause, and Palestine is more valuable to us than oil. Oil can be used as a weapon in battle if necessary. The Palestinian people must return to their homeland, even if it costs us all our lives.”[135]

- Addressing the president of the American Tapline Company, King Faisal said: "Any drop of oil that goes to Israel will make me cut off the oil for you."[136]

- The BBC conducted an interview with King Faisal. During the interview, the reporter asked him "what event you would like to see happen now in the Middle East." The king replied, "The first thing is the demise of Israel."[137]

- When oil was cut off from the United States during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, Henry Kissinger told Faisal "If Saudi Arabia does not lift the boycott, America will come and bomb the oilfields." King Faisal replied back "You are the ones who can't live without oil. You know, we come from the desert, and our ancestors lived on dates and milk and we can easily go back and live like that again."[136]

- Henry Kissinger said in his memoirs that when he met King Faisal in Jeddah the king was sad, so he told a joke to King Faisal, "My plane ran out of oil so will your majesty order it to get supplied with oil and we are ready to pay at international rates?" Unamused, King Faisal said to Kissinger, "And I'm an old man who wishes to pray in Al-Aqsa before I die so will you help me in my wish?" At supper Faisal remarked to Kissinger, "You must have noticed, nothing in this dinner tonight carries foreign mark. The meat on the table comes from locally hunted camels. The delicacies all made on Arab land, from Arab resources. The lamps that give us light tonight, burn on fuel extracted from camel fat. If you dare come here, we would set our wells on fire and wander into the deserts. We, as you see, would survive. What would you do?"[138]

Honors

| Styles of King Faisal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Majesty |

Faisal has received numerous honors from the countries he visited both before and after assuming power.[139] In 1983, the King Faisal Foundation, an international philanthropic organization founded by King Faisal's sons, established the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies in Riyadh.[124] The honors and awards given to King Faisal are displayed there.[139] The awards are as follows:

Afghanistan, Order of the Sun and Collar, Order of Independence[139]

Afghanistan, Order of the Sun and Collar, Order of Independence[139] Belgium, Order of Leopold[139]

Belgium, Order of Leopold[139] Chad, National Order of Chad[139]

Chad, National Order of Chad[139] Egypt, Order of Ismial (Kingdom), Order of the Nile Collar (Kingdom), and Order of the Nile Collar (Republic)[139]

Egypt, Order of Ismial (Kingdom), Order of the Nile Collar (Kingdom), and Order of the Nile Collar (Republic)[139] France, Legion of Honor (First and Second Class)[139]

France, Legion of Honor (First and Second Class)[139] Greece, Order of George I[139]

Greece, Order of George I[139] Guinea, The National Order[139]

Guinea, The National Order[139] Indonesia, Order of the Republic[139]

Indonesia, Order of the Republic[139] Iran, Order of Pahlavi with collar and Order of Taj[139]

Iran, Order of Pahlavi with collar and Order of Taj[139] Iraq, Order of El-Rafidain and Order of Faisal I[139]

Iraq, Order of El-Rafidain and Order of Faisal I[139] Italy, Order of the Crown[139]

Italy, Order of the Crown[139] Japan, Collar of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum[139]

Japan, Collar of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum[139]

Jordan, Order of Al Hussein - Collar only and Order of Al Nahda (twice)[139]

Jordan, Order of Al Hussein - Collar only and Order of Al Nahda (twice)[139] Korea, Order of Distinguished Diplomatic Service[139]

Korea, Order of Distinguished Diplomatic Service[139] Lebanon, Order of the Cedar[139]

Lebanon, Order of the Cedar[139] Liberia, Order of the Pioneers of Liberia[139]

Liberia, Order of the Pioneers of Liberia[139] Libya, Order of Idris I (Kingdom)[139]

Libya, Order of Idris I (Kingdom)[139] Malaysia, Order of the Crown[139]

Malaysia, Order of the Crown[139] Mauritania, Order of Mauritania[139]

Mauritania, Order of Mauritania[139] Morocco, Order of Mohammed - Collar only[139]

Morocco, Order of Mohammed - Collar only[139] Netherlands, Order of Orange-Nassau[139]

Netherlands, Order of Orange-Nassau[139] Niger, National Order of Niger and Order of Merit of Niger[139]

Niger, National Order of Niger and Order of Merit of Niger[139] Oman, Order of Oman - Military and Collar[139]

Oman, Order of Oman - Military and Collar[139] Poland, Order of Polonia Restiituta[139]

Poland, Order of Polonia Restiituta[139] Pakistan, Order of Imtiaz and Order of Pakistan[139]

Pakistan, Order of Imtiaz and Order of Pakistan[139] Saudi Arabia, Order of King Abdulaziz[140]

Saudi Arabia, Order of King Abdulaziz[140] Senegal, Order of Merit of Senegal[139]

Senegal, Order of Merit of Senegal[139] Somalia, Order of the Somali Star and Collar[139]

Somalia, Order of the Somali Star and Collar[139] Spain, The Order of Civil Merit and Collar[139]

Spain, The Order of Civil Merit and Collar[139] Sudan, Collar of Honor[139]

Sudan, Collar of Honor[139] Syria, Order of Omayyad[139]

Syria, Order of Omayyad[139] Taiwan, Order of Brilliant Jade with Grand Cordon and Order of Brilliant Star[141]

Taiwan, Order of Brilliant Jade with Grand Cordon and Order of Brilliant Star[141] Tunisia, Order of Iftikhar and Order of Independence and Collar[139]

Tunisia, Order of Iftikhar and Order of Independence and Collar[139] Turkey, Gold Red Crescent Medal[139]

Turkey, Gold Red Crescent Medal[139] Uganda, Order of the Nile[139]

Uganda, Order of the Nile[139] United Kingdom, Royal Victorian Chain, Order of the British Empire, and Order of St. Michael and St. George (2nd Class)[139]

United Kingdom, Royal Victorian Chain, Order of the British Empire, and Order of St. Michael and St. George (2nd Class)[139] Zaire, Order of the Leopard[139]

Zaire, Order of the Leopard[139]

Notes

- ^ King Abdulaziz's eldest son, Turki I bin Abdulaziz, was born to Wadha bint Muhammad Al Orair. Prince Turki was the heir to his father, but he died in 1919. King Abdulaziz's next eldest son, and Prince Turki's full brother, would eventually ascend as King Saud in 1953.

- ^ King Abdulaziz's other sons who became kings were Saud, Khalid, Fahd, Abdullah, and Salman.

- ^ The king associated Communism with Zionism, which he also opposed.[2]

- ^ He also had many half-siblings, a number of whom would play an important role in his life and his reign, including King Saud, King Khalid, King Fahd, King Abdullah, and Prince Sultan.

References

- ^ Nabil Mouline (2014). The Clerics of Islam. Religious Authority and Political Power in Saudi Arabia. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. p. 121. doi:10.12987/yale/9780300178906.001.0001. ISBN 9780300178906.

- ^ a b c "Unexpectedly modern". The Economist. 26 January 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ a b "King Faisal: Oil, Wealth and Power" Archived 26 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine, TIME Magazine, 7 April 1975.

- ^ George Kheirallah (1952). Arabia Reborn. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 254. ISBN 9781258502010. Archived from the original on 10 June 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ^ a b c "The kings of the Kingdom". Ministry of Commerce and Industry. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ Nabil Mouline (April–June 2012). "Power and generational transition in Saudi Arabia" (PDF). Critique Internationale. 46: 1–22.

- ^ Paul L. Montgomery (26 March 1975). "Rise of a Desert Chief's Son to the World Power and Riches". Rutland Daily Herald. Times News Service. p. 2i. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ a b Winberg Chai (22 September 2005). Saudi Arabia: A Modern Reader. University Press of America. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-88093-859-4. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018.

- ^ "Wahhabism – A Unifier or a Divisive Element". APS Diplomat News Service. 7 January 2013. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Alexander Bligh (1985). "The Saudi religious elite (Ulama) as participant in the political system of the kingdom". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 17: 37–50. doi:10.1017/S0020743800028750.

- ^ "Riyadh. The capital of monotheism" (PDF). Business and Finance Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2009.

- ^ As'ad AbuKhalil (2004). The Battle for Saudi Arabia. Royalty, fundamentalism and global power. New York City: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 1-58322-610-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "في ذكري ميلاده.. تعرف على أهم أسرار حياة الملك فيصل آل سعود". Elzman News (in Arabic). 14 April 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ Helen Chapin Metz, ed. (1992). Saudi Arabia: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. ISBN 9780844407913. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Susan Rose (25 November 2020). The Naval Miscellany: Volume VI. Taylor & Francis. p. 433. ISBN 978-1-00-034082-2.

- ^ a b c d Hassan Abedin (2003). Abdulaziz Al Saud and the great game in Arabia, 1896-1946 (PDF) (PhD thesis). King's College. p. 146. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ a b Leon Hesser (30 November 2004). Nurture the Heart, Feed the World: The Inspiring Life Journeys of Two Vagabonds. BookPros, LLC. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-9744668-8-0.

- ^ Mark Weston (28 July 2008). Prophets and Princes: Saudi Arabia from Muhammad to the Present. John Wiley & Sons. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-470-18257-4. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018.

- ^ Mohammad Zaid Al Kahtani (December 2004). The Foreign Policy of King Abdulaziz (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Leeds. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ a b c Nora Derbal (2020). "Humanitarian Service in the Name of Social Development: The Historic Origins of Women's Welfare Associations in Saudi Arabia". In E. Möller; J. Paulmann; K. Stornig (eds.). Gendering Global Humanitarianism in the Twentieth Century. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. pp. 167–192. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-44630-7_7. ISBN 978-3-030-44629-1. S2CID 226630086.

- ^ a b c "Fayṣal (King of Saudi Arabia)". Encyclopedia Britannica. 20 July 1998.

- ^ Alexander Blay Bligh (1981). Succession to the throne in Saudi Arabia. Court Politics in the Twentieth Century (PhD thesis). Columbia University. p. 57. ProQuest 303101806. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Ghassane Salameh; Vivian Steir (October 1980). "Political Power and the Saudi State". MERIP (91): 5–22. doi:10.2307/3010946. JSTOR 3010946.

- ^ a b Charles W. Harrington (Winter 1958). "The Saudi Arabian Council of Ministers" (PDF). The Middle East Journal. 12 (1): 1–19. JSTOR 4322975.

- ^ "Mofa.gov.sa". Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ Turki bin Khalid bin Saad bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (2015). Saudi Arabia-Iran relations 1929-2013 (PDF) (PhD thesis). King's College London. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ T. R. McHale (Autumn 1980). "A Prospect of Saudi Arabia". International Affairs. 56 (4): 622–647. doi:10.2307/2618170. JSTOR 2618170.

- ^ "Seminar focuses on King Faisal's efforts to promote world peace". Arab News. 30 May 2002. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- ^ Hakan Özoğlu (2019). "Heirs of the Empire: Turkey's diplomatic ties with Egypt and Saudi Arabia until the mid-20th century". In Gönül Tol; David Dumke (eds.). Aspiring Powers, Regional Rivals (PDF). Washington DC: Middle East Institute. p. 12. ISBN 9798612846444.

- ^ a b c Odah Sultan Odah (1988). Saudi-American relation 1968-78: A study in ambiguity (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Salford. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ "شاهد 90 عاما للأقصى.. أبرز المبادرات السعودية لدعم القضية الفلسطينية (إنفوجراف)". Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Montgomery, Paul L. (26 March 1975). "Faisal, Rich and Powerful, Led Saudis Into 20th Century and to Arab Forefront". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Mai Yamani (January–March 2009). "From fragility to stability: A survival strategy for the Saudi monarchy". Contemporary Arab Affairs. 2 (1): 90–105. doi:10.1080/17550910802576114.

- ^ Richard Cavendish (2003). "Death of Ibn Saud". History Today. 53 (11).

- ^ "Ibn Saud dies". King Abdulaziz Information Source. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ "Saud Names His Brother Prime Minister of Nation". The New York Times. Jeddah. Associated Press. 17 August 1954. ProQuest 112933832.

- ^ a b c "King Faisal". LookLex Encyclopaedia. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017.

- ^ "About Ministry of Finance". www.mof.gov.sa.

- ^ Alexei Vassiliev. (1998). The History of Saudi Arabia, London, UK: Al Saqi Books, 978-0863569357, p. 358

- ^ a b Rosie Bsheer (August 2017). "W(h)ither Arabian Peninsula Studies?". In Amal Ghazal; Jens Hanssen (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Middle-Eastern and North African History. Oxford. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199672530.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-967253-0. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021.

- ^ a b Nadav Safran (1985). Saudi Arabia: The Ceaseless Quest for Security. Cornell University Press. pp. 94–217. ISBN 978-0-8014-9484-0. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ "Chapter II: The reign of King Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud". Moqatel. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Abdullah Hamad Al Salamah (April 1994). Employee Perceptions in Multinational Companies: A Case Study of the Saudi Arabian Basic Industries Corporation (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Durham. Retrieved 14 April 2021.

- ^ a b Rachel Bronson (2005). "Rethinking Religion: The Legacy of the US–Saudi Relationship" (PDF). The Washington Quarterly. 28 (4): 121–137. doi:10.1162/0163660054798672. S2CID 143684653.

- ^ "A history of treason – King Faisal bin Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud". Islam Times. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ a b James Wynbrandt. (2004). A Brief History of Saudi Arabia, New York: Facts on File, Inc., pp. 221-225. ISBN 9780816078769.

- ^ a b Vassiliev, pp. 366–7

- ^ a b Joseph A. Kechichian (2001). Succession in Saudi Arabia. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 9780312238803.

- ^ Mordechai Abir (1987). "The Consolidation of the Ruling Class and the New Elites in Saudi Arabia". Middle Eastern Studies. 23 (2): 156. doi:10.1080/00263208708700697.

- ^ a b David Rundell (17 September 2020). Vision or Mirage: Saudi Arabia at the Crossroads. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-83860-594-0. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia" (Country Readers Series). Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. p. 77. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Alexei Vassiliev (1 March 2013). King Faisal: Personality, Faith and Times. Saqi. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-86356-761-2.

- ^ Nawaf E. Obaid (September 1999). "The Power of Saudi Arabia's Islamic Leaders". Middle East Quarterly.

- ^ Peter Bergen. (2006). "The Osama bin Laden I Know'.

- ^ Esther van Eijk (2010). "Sharia and national law in Saudi Arabia". In Jan Michiel Otto (ed.). Sharia Incorporated. Leiden: Leiden University Press. p. 148. ISBN 9789087280574.

- ^ Vassiliev p. 395.

- ^ Saudi Arabia Diplomatic Handbook Foreign Policy, Strategi Information and Developments. International Business Publications, USA. 2009. p. 52. ISBN 9781438742359.

- ^ a b Vassiliev 371.

- ^ Official website of the Saudi Deputy Minister of Defense, official Saudi government journal Umm Al-Qura Issue 2193, 20 October 1967 Archived 6 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Joshua Tietelbaum. "A Family Affair: Civil-Military Relations in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia" (PDF). p. 11. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2008.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Roham Alvandi (2012). "Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: the origins of Iranian primacy in the Persian Gulf" (PDF). Diplomatic History. 36 (2): 337–372. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.2011.01025.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2013.

- ^ a b Mai Yamani (February–March 2008). "The two faces of Saudi Arabia". Survival. 50 (1): 143–156. doi:10.1080/00396330801899488.

- ^ Fakhruddin Owaisi. "Sayyid Muhammad bin 'Alawi Al-Maliki al-Hasani: A Biography". Imam Ghazali Institute. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Andrea Brigaglia (2013). "Two Exegetical Works from Twentieth-Century West Africa: Shaykh Abu Bakr Gumi's Radd al-adhhān and Shaykh Ibrahim Niasse's Fī riyāḍ al-tafsīr". Journal of Qur'anic Studies. 15 (3): 253–266. doi:10.3366/jqs.2013.0120.

- ^ Muhammad Husayn Ibrahimi, Mansoor Limba, and Sunitas y Chiitas. (2007). A new analysis of Wahhabi doctrines. Ahl al-Bayt World Assembly.

- ^ a b Mordechai Abir (1987). "The Consolidation of the Ruling Class and the New Elites in Saudi Arabia". Middle Eastern Studies. 23 (2): 150–171. doi:10.1080/00263208708700697. JSTOR 4283169.

- ^ "Educated for indolence". The Guardian. 2 August 1999. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ A Blessed Gathering Between King Faisal, Shaykh Abdullah ibn Humaid & Shaykh ibn Baz, archived from the original on 31 October 2021, retrieved 14 August 2021

- ^ a b Michel G. Nehme (1994). "Saudi Arabia 1950–80: Between Nationalism and Religion". Middle Eastern Studies. 30 (4): 930–943. doi:10.1080/00263209408701030. JSTOR 4283682.

- ^ Bruce Riedel (2011). "Brezhnev in the Hejaz" (PDF). The National Interest. 115. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2013.

- ^ Robert R. Sullivan (October 1970). "Saudi Arabia in International Politics". The Review of Politics. 32 (4): 439. JSTOR 1405899.

- ^ King Faisal Ibn Abdul Aziz Al Saud. The Saudi Network Archived 30 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Elaine Sciolino (4 November 2001). "U.S. Pondering Saudis' Vulnerability". The New York Times. Washington. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ "Saudi airforce order to go to war from Riyadh". Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ "بطولات السعوديين حاضرة.. في الحروب العربية". Okaz. 17 November 2019. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Saudi Arabia Diplomatic Handbook Foreign Policy, Strategi Information and Developments. International Business Publications, USA. 2009. p. 53. ISBN 9781438742359.

- ^ "Interview: Prince Amr bin Mohammed al-Faisal". PBS. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Alexei Vassiliev. (2012). King Faisal of Saudi Arabia: Personality, Faith and Times. Saqi. ISBN 978-0-86356-689-9. pp. 333-334

- ^ Smith, Charles D. (2006), Palestine and the Arab–Israeli Conflict, New York: Bedford, p. 329.

- ^ "OPEC Oil Embargo 1973–1974". U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ "Person of the Year". TIME Magazine. 183 (9). 10 March 2014. Archived from the original on 7 January 2007.

- ^ Muhammad Hassanein Heykal (Summer 1977). "The Saudi Era". Journal of Palestine Studies. 6 (4): 158–164. doi:10.2307/2535788. JSTOR 2535788.

- ^ Fred Halliday (11 August 2005). "Political killing in the cold war". Open Democracy. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018.

- ^ William B. Quandt (1981). Saudi Arabia in the 1980s: Foreign Policy, Security, and Oil. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution. p. 79. ISBN 0815720513.

- ^ a b Jennifer S. Uglow; Frances Hinton; Maggy Hendry (1999). The Northeastern Dictionary of Women's Biography. UPNE. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-55553-421-9.

- ^ Ghada Talhami (1 December 2012). Historical Dictionary of Women in the Middle East and North Africa. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8108-6858-8.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia mourns passing away of princess". Kuwait News Agency. 12 February 2000. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ "King Faisal Assassinated." Archived 10 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine Lewiston Evening Journal, Lewiston-Auburn, Maine 25 March 1975: 1+. Print.

- ^ Mark Weston (28 July 2008). Prophets and Princes: Saudi Arabia from Muhammad to the Present. John Wiley & Sons. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-470-18257-4. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ David Leigh; Rob Evans (8 June 2007). "BAE Files: Kamal Adham". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ Dean Baquet (30 July 1992). "After Plea Bargain by Sheik, Question Is What He Knows". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Nick Luddington (5 April 1975). "King Faisal's eight sons". Lewiston Evening Journal. Jeddah. AP. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia" (Country Readers Series). Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. p. 57. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ Joseph A. Kechichian (2014). 'Iffat Al Thunayan: an Arabian Queen. Sussex Academic Press. p. 64. ISBN 9781845196851.

- ^ Mordechai Abir (1988). Saudi Arabia in the Oil Era: Regime and Elites: Conflict and Collaboration. Kent: Croom Helm. ISBN 9780709951292. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016.

- ^ "Death of Princess Hussah bint Faysal". SPA. 3 December 2020. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ a b Sharaf Sabri. (2001). The House of Saud in Commerce: a Study of Royal Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. New Delhi: I.S. Publications. Print.

- ^ a b Mark Weston (28 July 2008). Prophets and Princes: Saudi Arabia from Muhammad to the Present. John Wiley & Sons. p. 450. ISBN 978-0-470-18257-4.

- ^ "The Life and Times of the Cautious King of Araby". Time Magazine. 102 (21). 19 November 1973.

- ^ "Reflections on US-Saudi Relations". Georgetown University. 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^ "Embassy official: Saudi ambassador to U.S. resigns". CNN. 2006. Archived from the original on 11 January 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- ^ "Saudi Royal Court: Prince Saad bin Faisal bin Abdulaziz dies". Sharjah 24. 11 April 2017. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "Breakthrough in Saudi Arabia: women allowed in parliament". Al Arabiya. 11 January 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ ""الشورى" السعودي الجديد.. خال من للمزيد". Al Qabas (in Arabic). 3 December 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Amélie Le Renard (2008). ""Only for Women:" Women, the State, and Reform in Saudi Arabia" (PDF). Middle East Journal. 62 (4): 622. JSTOR 25482571.

- ^ "Princess Haifa bint Faisal al Saud". Manhom. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Ana Echagüe; Edward Burke (June 2009). "'Strong Foundations'? The Imperative for Reform in Saudi Arabia" (PDF). FRIDE (Spanish Think-tank organization). pp. 1–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ "Princess Mashael bint Faisal passes away". Life in Riyadh. 3 October 2011. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ Joobin Bekhrad (1 March 2016). "Shiny Happy People". Reorient. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ "Chris Hardwick sold his house to Princess Reem Al Faisal". Dirt. 12 October 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ "Man in the news. King Faisal". The Telegraph. 5 November 1964. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ^ "صفات الملك فيصل رحمه الله". Almrsal. 15 January 2019. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "من الصيد بالصقور إلى المطالعة والسباحة: هذه هوايات ملوك السعودية". Arrajol. 23 September 2020. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Fahd Al Semmari (Summer 2001). "The King Abdulaziz Foundation for Research and Archives". Middle East Studies Association Bulletin. 35 (1): 45–46. doi:10.1017/S0026318400041432. JSTOR 23063369.

- ^ James Wynbrandt (2010). A Brief History of Saudi Arabia. Infobase Publishing. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-8160-7876-9. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ a b c "1975: Saudi's King Faisal assassinated". BBC. 25 March 1975. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Geoffrey King (1978). "Traditional Najdī Mosques" (PDF). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 41 (3): 473. JSTOR 615491.

- ^ Abdul Nabi Shaheen (23 October 2011). "Sultan will have simple burial at Al Oud cemetery". Gulf News. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Michael Ross (26 March 1975). "Brother of murdered King assumes throne". Times Union. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ^ Nick Ludington. (24 March 1975) Public Execution Expected. Archived 10 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine Daily News [Bowling Green, Kentucky], p. 5.

- ^ David Commins (2006). The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia. p. 110. ISBN 1-84511-080-3.

- ^ King Faisal of Saudi Arabia - وثائقي عن الملك فيصل بن عبدالعزيز, archived from the original on 31 October 2021, retrieved 17 June 2021

- ^ سيرة الملك فيصل بن عبدالعزيز آل سعود في برنامج الراحل مع محمد الخميسي (in Arabic), archived from the original on 31 October 2021, retrieved 17 June 2021

- ^ a b "King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies (KFCRIS)". Datarabia. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ "The Sounds of the '60s: How Dick Dale, the Doors, and Dylan Swayed to Arab Music". Alternet. 3 December 2008. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ Natana J. DeLong-Bas (2011). "Faisal: King of Saudi Arabia. By Gerald de Gaury. (Louisville, Ky.: Fons Vitae, 2008. p. xiv, 191.)". The Historian. 73 (1): 117–118. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.2010.00288_2.x. S2CID 145473673.

- ^ "Born a King (2019)". IMDb. 26 September 2019. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ Mujtaba Razvi (1981). "PAK-Saudi Arabian Relations: An Example of Entente Cordiale" (PDF). Pakistan Horizon. 34 (1): 81–92. JSTOR 41393647.

- ^ Shahid Javed Burki (2018). Historical Dictionary of Pakistan. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-4422-4148-0. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ a b Sabir Shah (15 February 2019). "Saudi Royals who have visited Pakistan till date". The News. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Pakistan Air Force". paf.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 26 June 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ "King Faisal Speech during Hajj in 1968". Moqatel. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ "King Faisal Speech during Hajj in 1967". Moqatel. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "King Faisal bin Abdulaziz". Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ "مواقف المملكة مع قضية فلسطين". Gharb Press Corporation. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ a b "الفيصل في الكلام: عن الملك فيصل بن عبد العزيز". Al-Ayyam Syrian newspaper. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ "أقوى 5 إجابات في القرن 20: "زوال إسرائيل" كان رد الملك فيصل على سؤال لـ BBC". Egyptian Light. 12 October 2015. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ Henry Kissinger (1 March 1982). Years of Upheaval. Little Brown & Co. ISBN 9780316285919.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Owain Raw-Rees (1998). "King Faisal OF Saudi Arabia, His Awards and the Saudi Order of King Faisal" (PDF). 49 (4). The Medal Collector. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "البترول العربى ليس بأغلى من الدم.. صفحات خالدة من مسيرة القائد العربي الملك فيصل". Al Ahram (in Arabic). 14 April 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "King Faisal meets President Chiang". Taiwan Today. 1 June 1971. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

External links

Quotations related to Faisal of Saudi Arabia at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Faisal of Saudi Arabia at Wikiquote Media related to Faisal bin Abdulaziz al Saud at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Faisal bin Abdulaziz al Saud at Wikimedia Commons

- 20th-century murdered monarchs

- 20th-century Saudi Arabian politicians

- 1970s murders in Saudi Arabia

- 1906 births

- 1975 deaths

- Anti-Zionism

- Assassinated Saudi Arabian politicians

- Burials at Al Oud cemetery

- Collars of the Order of Civil Merit

- Crown Princes of Saudi Arabia

- Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques

- Deaths by firearm in Saudi Arabia

- Finance ministers of Saudi Arabia

- Foreign ministers of Saudi Arabia

- Grand Cross of the Order of Civil Merit

- Interior ministers of Saudi Arabia

- Kings of Saudi Arabia

- Prime Ministers of Saudi Arabia

- Saudi Arabian anti-communists

- Saudi Arabian Sunni Muslims

- Sons of Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia