Holiest sites in Islam

The four holiest sites in Islam are the Kaaba inside the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca as the holiest of the four, followed by Al-Masjid an-Nabawi in Medina, Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem and the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus; these sites are accepted in this order by the overwhelming majority of Islamic sects which are all held in high esteem.[2][3][4][5][6] The two holiest sites of Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia are directly mentioned or referred to in the Quran.[1][7][8][9][2][10]

In Shia Islam, after the first four sites, the Imam Ali Mosque in Najaf and the Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala, Fatimah Masumeh Shrine in Qom are the holiest sites.[11] For Sufi Muslims, after the first four sites, Mazar Ghous in Baghdad, Iraq, is the holiest site, followed by Data Darbar in Lahore, Pakistan. Sunni Muslims consider the Omar ibn al-Khattab Mosque and Abu Bakr Mosque very holy. There are also other sacred sites in Mecca that Muslims performing Hajj visit, namely Mount Arafat and Muzdalifah.[12]

Hejaz

Hejaz is the region in the Arabian Peninsula where Mecca and Medina are located. It is thus where Muhammad was born and raised.[13]

Mecca

Mecca is considered the holiest city in Islam, as it is home to Islam's holiest site Kaaba ('Cube') in the Masjid Al-Ḥaram (The Sacred Mosque).[1][2] Only Muslims are allowed to enter this place.[14]

The area of Mecca, which includes Mount Arafah,[15] Mina and Muzdalifah, is important for the Ḥajj ('Pilgrimage'). As one of the Five Pillars of Islam,[16] every adult Muslim who is capable must perform the Hajj at least once in their lifetime.[17] Hajj is one of the largest annual Muslim gatherings in the world, second only to pilgrimages to the mosques of Husayn ibn Ali and his half-brother Abbas in Karbala, Iraq, with attendance reaching 3 million in 2012.[18]

Medina

Al-Masjid an-Nabawi is located in Medina, making the city the second-holiest site in Islam, after Mecca. Medina is the final place-of-residence of Muhammad, and where his qabr (grave) is located.[1] In addition to the Prophet's Mosque, the city has the mosques of Qubā’[19] and al-Qiblatayn ("The Two Qiblahs").[20]

Shaam

Shaam (Arabic: شَّـام) [3] is a historical region that includes the cities of Jerusalem and Damascus.[3][21][22]

Jerusalem

Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem is the third holiest site in Islam. The covered mosque building was originally a small prayer house erected by Omar, the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate. The mosque is held in esteem by the entire Muslim community, due to its history as a place of worship by many Islamic prophets such as Ibrahim,[2] Dawud, Sulaimaan, Ilyas and Isa. The mosque has the capacity to accommodate in the region of 5,000 worshipers.[23] The mosque was the first direction of prayer (Qibla) before the Kaaba in Mecca. Muslims believe that Muhammad was taken from Masjid Al-Haram, to visit Masjid al-Aqsa, where he led the prayer among prophets, and was then taken to the heavens, in a single night in the year 620. References to the Al-Aqsa Mosque exist in the following verses of the Qur'an:

Damascus

Umayyad Mosque in Damascus is the fourth holiest site in Islam.[4][5][6] One of the four authorized copies of the Quran was kept here, and the head of the Islamic prophet Yahya is believed to be in the shrine. It is also holy to very Shia Muslims since there are shrines commemorating Husayn ibn Ali and the Ahl al-Bayt, made to walk here from Iraq, after the Battle of Karbala.[32] Furthermore, it was the place where they were imprisoned for 60 days.[33] Umayyad Mosque is also the place where Muslims believe Isa (Jesus) will return from the Minaret of Isa in the mosque. The Minaret of Isa in the Umayyad Mosque is dedicated to Islam's penultimate prophet Isa (Jesus), and it is believed that he will return to the world at the minaret during the time of a Fajr prayer and it is believed that he will pray at the mosque with the Mahdi. It is believed that prayers in the mosque are considered to be equal to those offered in Jerusalem.[4]

Hebron

In Islamic beliefs, Hebron was where Abraham (Ibrāhīm) settled. Within the city lies the Sanctuary of Abraham, the traditional burial site of the biblical Patriarchs and Matriarchs, and the Ibrahimi Mosque built on top of the tomb to honor the prophet.[34][35][36][37] Muslims believe that Muhammad visited Hebron on his nocturnal journey from Mecca to Jerusalem to stop by the tomb and pay his respects.[34] In the mosque in a small niche there is a left footprint, believed to be from Muhammad.[37][38]

Sinai peninsula

The Sinai peninsula is associated with the Islamic prophets Haroon and Musa.[39] In particular, numerous references to Mount Sinai exist in the Quran,[40][41] where it is called Ṭūr Sīnāʾ,[42] Ṭūr Sīnīn,[43] and aṭ-Ṭūr[44][45] and al-Jabal (both meaning "the Mount").[46] As for the adjacent Wād Ṭuwā (Valley of Tuwa), it is considered as being muqaddas[47][48] (sacred),[49][50] and a part of it is called Al-Buqʿah Al-Mubārakah ("The Blessed Place").[45]

Uzbekistan

The city Bukhara in Uzbekistan (which is associated with Imam Al-Bukhari) is considered as a holy city in Islam.[51][52]

Africa

Harar

According to UNESCO, Harar in eastern Ethiopia has 82 mosques, three of which date from the 10th century and 102 shrines.[53][54]

Kairouan

The most important mosque in Kairouan in Tunisia is the Great Mosque of Sidi-Uqba (Uqba ibn Nafi'). It has been said that seven pilgrimages to this mosque is considered the equivalent of one pilgrimage to Mecca.[55] After its establishment, Kairouan became an Islamic and Qur'anic learning centre in North Africa. An article by Professor Kwesi Prah[56] describes how during the medieval period. Kairouan was considered the third holiest site in Islam after Mecca and Medina by its citizens.[57][58]

Sunni Islam

In Sunni Islam, all sites which have been mentioned in the Hadith are holy to Sunni Muslims. The Kaaba is the holiest site, followed by the Al-Masjid an-Nabawi (The Prophet's Mosque), Al-Aqsa Mosque, and other sites mentioned in the Hadith, as well Umayyad Mosque, Ibrahimi Mosque.

Kaaba

The Kaaba or Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, is the most sacred holy place of Islam and a Qibla of the Muslims, contains al-Bayt ul-Ma'mur spiritually above the Kaaba, contains the Maqam Ibrahim, Hateem, and the Al-Hajar-ul-Aswad which was belong to Jannah and Adam and Eve (Adam and Hawa), According to the Islamic tradition it was first built by the first Islamic prophet Adam, after Noah's Flood (Flood of the Islamic prophet Nūḥ), it was rebuilt by Islamic prophet Abraham (ʾIbrāhīm) and his son the Islamic prophet Ishmael (Ismā‘īl), it has been rebuilt several times.

al-Masjid an-Nabawi

The Al-Masjid an-Nabawi or the Prophet's Mosque in Medina, contains the grave of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

The two companions Abu Bakr and Omar are also buried with the Holy prophet of Islam, the grave of Uthman in located in the Al-Baqi' cemetery located to the southeast of the Prophet's Mosque, while the grave of Ali and is in Kufa. The grave of al-Hasan is also in al-Baqi' while al-Husayn is buried in Kufa.

al-Aqsa Mosque

The al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, was the first qibla of the Muslims, According to the tradition, prophet Muhammad was Imam of all the prophets in the mosque, the mosque was ordered to built by the Islamic prophet Solomon (Sulaymān), son of the Islamic prophet David (Dāwūd), who was sent to the Israelites, prophet Solomon ordered the Jinns to built the mosque.

Others

- The Damascus Mosque, is also considered the sacred mosque for the Muslims, and it is believed that the Islamic prophet Jesus (ʿĪsā ibn Maryam) will return in this mosque.

- The Ibrahimi Mosque, contains the burial of the prophet Ibrahim and few of his family members.

Shia Islam

After the four mosques accepted by all Muslims as holy sites, the Shia Muslims consider Imam Ali Masjid in Najaf as the holiest site of only Shia Muslims, followed by Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala and then the Fatima Masumeh Shrine in Qom, Iran.

Imam Ali Mosque

Imam Ali Mosque in Najaf, Iraq is the holiest site for Shia Muslims as the first Shia Imam Ali was buried here. The site is visited annually by at least 8 million pilgrims on average, which is estimated to increase to 20 million in years to come.

Imam Husayn Shrine

Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala, Iraq is the second most holiest site for Shia Muslims. It contains the tomb of Husayn ibn Ali. The mosque stands on the site of the grave of Hussein ibn Ali, where he was martyred during the Battle of Karbala in 680.[59][60] Up to a million pilgrims visit the city for the anniversary of Hussein ibn Ali's death.[61] There are many Shia traditions which narrate the status of Karbala.

Fatima Masumeh Shrine

Fatima Masumeh Shrine in Qom, Iran contains the tomb of Fātimah bint Mūsā, sister of the eighth Shia Imam, Ali al-Rida. Located in Qom, Iran, it has been considered the Fatima Masumeh Shrine to be the third holiest shrine in Shia Islam.[11] The shrine has attracted to itself dozens of seminaries and religious schools.

Sufi Islam

Mazar Ghous

Mazar Ghous in Baghdad, Iraq is the holiest site in Sufi Islam. It is dedicated to the founder of Qadiryya Sufi order, Abdul Qadir Gilani. The complex was built near the Bab al-Sheikh (ash-Sheikh Gate) in al-Rusafa.[62][63][64]

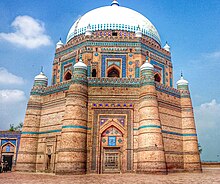

Tomb of Shah Rukn-e-Alam

Tomb of Shah Rukn-e-Alam in Multan is considered the third most holiest site in Sufi Islam. It is the mausoleum of Multan's Sufi saint Sheikh Rukn-ud-Din Abul Fateh. It is one of the most impressive shrines in the world.[65] The shrine attracts over 100,000 pilgrims to the annual Urs festival that commemorates his death.

See also

- Ḥ-R-M

- Lists of mosques

- List of largest mosques

- List of mosques

- Middle East

- Near East

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Trofimov, Yaroslav (2008), The Siege of Mecca: The 1979 Uprising at Islam's Holiest Shrine, New York, p. 79, ISBN 978-0-307-47290-8

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Michigan Consortium for Medieval and Early Modern Studies (1986). Goss, V. P.; Bornstein, C. V. (eds.). The Meeting of Two Worlds: Cultural Exchange Between East and West During the Period of the Crusades. 21. Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University. p. 208. ISBN 0918720583.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Mustafa Abu Sway. "The Holy Land, Jerusalem and Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Qur'an, Sunnah and other Islamic Literary Source" (PDF). Central Conference of American Rabbis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Janet L. Abu-Lughod (contributor) (2007). "Damascus". In Dumper, Michael R. T.; Stanley, Bruce E. (eds.). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 119–126. ISBN 978-1-5760-7919-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sarah Birke (2013-08-02), Damascus: What's Left, New York Review of Books

- ^ Jump up to: a b Totah, Faedah M. (2009). "Return to the origin: negotiating the modern and unmodern in the old city of Damascus". City & Society. 21 (1): 58–81. doi:10.1111/j.1548-744X.2009.01015.x.

- ^ Quran 9:25–129

- ^ Quran 33:09–73

- ^ Quran 63:1–11

- ^ Quran 48:22–29

- ^ Jump up to: a b Escobar, Pepe (May 24, 2002). "Knocking on heaven's door". Central Asia/Russia. Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on June 3, 2002. Retrieved 2006-11-12.

To give a measure of its importance, according to a famous hadith (saying) - enunciated with pleasure by the guardians of the shrine - we learn that ‘our sixth imam, Imam Sadeg, says that we have five definitive holy places that we respect very much. The first is Mecca, which belongs to God. The second is Medina, which belongs to the Holy Prophet Muhammad, the messenger of God. The third belongs to our first imam of Shia, Ali, which is in Najaf. The fourth belongs to our third imam, Hussein, in Kerbala. The last one belongs to the daughter of our seventh imam and sister of our eighth imam, who is called Fatemah, and will be buried in Qom. Pilgrims and those who visit her holy shrine, I promise to these men and women that God will open all the doors of Heaven to them.’

CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Geomatika Advanced Solutions (6 June 2016). Atlas of MAKKAH, Dr. Osama bin Fadl Al-Bahar: Makkah City. Bukupedia. pp. 104–. GGKEY:YLPLD6B31C2.

- ^ Hopkins, Daniel J.; 편집부 (2001). Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary. p. 479. ISBN 0-87779-546-0. Retrieved 2013-03-17.

- ^ Tucker & Roberts 2008, p. 673.

- ^ Quran 2:124–217

- ^ Musharraf 2012, p. 195.

- ^ Peters 1994, p. 22.

- ^ Blatt 2015, p. 27.

- ^ Description of the new mosque and architectural documents at archnet.org Archived January 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "CRCC: Center For Muslim-Jewish Engagement: Resources: Religious Texts". Usc.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-01-07. Retrieved 2011-01-12.

- ^ Bosworth, C. E. (1997). "AL-SHĀM". Encyclopaedia of Islam. 9. p. 261.

- ^ Salibi, K. S. (2003). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. I. B. Tauris. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-1-86064-912-7.

To the Arabs, this same territory, which the Romans considered Arabian, formed part of what they called Bilad al-Sham, which was their own name for Syria. From the classical perspective however Syria, including Palestine, formed no more than the western fringes of what was reckoned to be Arabia between the first line of cities and the coast. Since there is no clear dividing line between what are called today the Syrian and Arabian deserts, which actually form one stretch of arid tableland, the classical concept of what actually constituted Syria had more to its credit geographically than the vaguer Arab concept of Syria as Bilad al-Sham. Under the Romans, there was actually a province of Syria, with its capital at Antioch, which carried the name of the territory. Otherwise, down the centuries, Syria like Arabia and Mesopotamia was no more than a geographic expression. In Islamic times, the Arab geographers used the name arabicized as Suriyah, to denote one special region of Bilad al-Sham, which was the middle section of the valley of the Orontes river, in the vicinity of the towns of Homs and Hama. They also noted that it was an old name for the whole of Bilad al-Sham which had gone out of use. As a geographic expression, however, the name Syria survived in its original classical sense in Byzantine and Western European usage, and also in the Syriac literature of some of the Eastern Christian churches, from which it occasionally found its way into Christian Arabic usage. It was only in the nineteenth century that the use of the name was revived in its modern Arabic form, frequently as Suriyya rather than the older Suriyah, to denote the whole of Bilad al-Sham: first of all in the Christian Arabic literature of the period, and under the influence of Western Europe. By the end of that century it had already replaced the name of Bilad al-Sham even in Muslim Arabic usage.

- ^ "al-Aqṣā mosque". doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_com_22686. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Surah Al-Ma'idah - 12". quran.com. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Quran 5:12–86

- ^ "Surah Al-Isra - 1". quran.com. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Quran 17:1–7

- ^ "Surah Al-Anbya - 51". quran.com. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Quran 21:51–82

- ^ "Surah Saba - 10". quran.com. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ Quran 34:10–18

- ^ Qummi, Shaykh Abbas (2005). Nafasul Mahmoom. Qum: Ansariyan Publications. p. 362.

- ^ Nafasul Mahmoom. p. 368.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vitullo, Anita (2003). "People Tied to Place: Strengthening Cultural Identity in Hebron's Old City". Journal of Palestine Studies. 33: 68–83. doi:10.1525/jps.2003.33.1.68. quote: From earliest Islam, the sanctuaries of Hebron and Jerusalem [al-Haram al-Ibrahimi and al-Haram al-Sharif] were holy places outranked only by Mecca and Medina; the Ibrahimi Mosque was originally regarded by some Muslims as Islam’s fourth holiest site. Muslims believe that the Hebron sanctuary was visited by the Prophet Muhammad on his mystical nocturnal journey from Mecca to Jerusalem.

- ^ Aksan & Goffman 2007, p. 97: 'Suleyman considered himself the ruler of the four holy cities of Islam, and, along with Mecca and Medina, included Hebron and Jerusalem in his rather lengthy list of official titles.'

- ^ Honigmann 1993, p. 886

- ^ Jump up to: a b Janet L. Abu-Lughod (contributor) (2007). "Damascus". In Dumper, Michael R. T.; Stanley, Bruce E. (eds.). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-1-5760-7919-5.

- ^ "Hebron: The city of Abraham, the Beloved". 2005-04-26.

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia

- ^ Sharīf, J.; Herklots, G. A. (1832). Qanoon-e-Islam: Or, The Customs of the Moosulmans of India; Comprising a Full and Exact Account of Their Various Rites and Ceremonies, from the Moment of Birth Till the Hour of Death. Parbury, Allen, and Company.

koh-e-toor.

- ^ Abbas, K. A. (1984). The World is My Village: A Novel with an Index. Ajanta Publications.

- ^ Quran 23:20 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)

- ^ Quran 95:2 (Translated by Yusuf Ali)

- ^ Quran 2:63–93

- ^ Jump up to: a b Quran 28:3–86

- ^ Quran 7:103–156

- ^ Quran 20:9–99

- ^ Quran 79:15–25

- ^ Ibn Kathir (2013-01-01). Dr Mohammad Hilmi Al-Ahmad (ed.). Stories of the Prophets: [قصص الأنبياء [انكليزي. Dar Al Kotob Al Ilmiyah (Arabic: دَار الْـكُـتُـب الْـعِـلْـمِـيَّـة). ISBN 978-2745151360.

- ^ Elhadary, Osman (2016-02-08). "11, 15". Moses in the Holy Scriptures of Judaism, Christianity and Islam: A Call for Peace. BookBaby. ISBN 978-1483563039.

- ^ Jones, Kevin. "Slavs and Tatars: Language arts." ArtAsiaPacific 91 (2014): 141.

- ^ Sultanova, Razia. From Shamanism to Sufism: Women, Islam and Culture in Central Asia. Vol. 3. IB Tauris, 2011.

- ^ Desplat, Patrick. "The Making of a ‘Harari’ City in Ethiopia: Constructing and Contesting Saintly Places in Harar." Dimensions of Locality: Muslim Saints, Their Place and Space 8 (2008): 149.

- ^ Harar - the Ethiopian city known as 'Africa's Mecca', BBC, 21 July 2017

- ^ Europa Publications Limited (30 October 2003). The Middle East and North Africa. Europa Publications. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-85743-184-1. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ Director, Centre for Advanced Study of African Societies, Cape Town, South Africa.

- ^ This was originally a paper submitted to the African Union (AU) Experts’ Meeting on a Strategic Geopolitic Vision of Afro-Arab Relations. AU Headquarters, Addis Ababa, 11–12 May 2004 Towards a Strategic Geopolitic Vision of Afro-Arab Relations. "By 670, the Arabs had taken Tunisia, and by 675, they had completed construction of Kairouan, the city that would become the premier Arab base in North Africa. Kairouan was later to become the third holiest city in Islam in the medieval period, after Mecca and Medina, because of its importance as the centre of the Islamic faith in the Maghrib".

- ^ Dr. Ray Harris; Khalid Koser (30 August 2004). Continuity and change in the Tunisian sahel. Ashgate. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7546-3373-0. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- ^ Shimoni & Levine, 1974, p. 160.

- ^ Aghaie, 2004, pp. 10-11.

- ^ "Interactive Maps: Sunni & Shia: The Worlds of Islam". PBS. Retrieved June 9, 2007.

- ^ Al-Ghunya li-talibi tariq al-haqq wa al-din (Sufficient provision for seekers of the path of truth and religion), parts one and two in Arabic, Al-Qadir, Abd and Al-Gilani. Dar Al-Hurya, Baghdad, Iraq, (1987).

- ^ Al-Ghunya li-talibi tariq al-haqq wa al-din (Sufficient provision for seekers of the path of truth and religion) with introduction by Al-Kilani, Majid Irsan. Al-Kilani, Majid, al-Tariqat, 'Ursan, and al-Qadiriyah, Nash'at

- ^ "The Qadirya Mausoleum" (PDF).

- ^ Asghar, Muhammad (2016). The Sacred and the Secular: Aesthetics in Domestic Spaces of Pakistan/Punjab. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783643908360.

Bibliography

- Aksan, Virginia H.; Goffman, Daniel (2007). The early modern Ottomans: remapping the Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81764-6. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- Peters, Francis (1994). The Hajj: The Muslim Pilgrimage to Mecca and the Holy Places. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691026190.

- Musharraf, Hussain (2012). The Five Pillars of Islam: Laying the Foundations of Divine Love and Service to Humanity. Leicestershire, UK: Kube Publishing. ISBN 9781847740236.

- Blatt, Amy (2015). Health, Science, and Place: A New Model. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-12003-4. ISBN 978-3319120027. S2CID 183074116.

- Tucker, Spencer; Roberts, Priscilla (2008). The encyclopedia of the Arab-Israeli conflict : a political, social, and military history. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851098415.

- Honigmann, Ernst (1993) [1927]. "Hebron". In Houtsma, M. T. (ed.). E.J. Brill's first encyclopedia of Islam, 1913–1936. IV. BRILL. pp. 886–888. ISBN 978-90-04-09790-2.

External links

- Islamic holy places