Federalism in the United Kingdom

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2020) |

Federalism in the United Kingdom refers to the distribution of power between constituent countries and regions of the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom, despite being composed of four countries (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland - the latter three having their own cabinet, legislature and First Minister) has traditionally been a unitary state governed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in Westminster. Instead of adopting a federal model, such as that of the United States, the United Kingdom employs a system of devolution, in which political power is gradually decentralised. Devolution differs from federalism in that regions have no constitutionally protected powers. As such, an Act of Parliament could undo devolution, whereas the federal United States government cannot revoke a state's powers.[1] Devolution has only been extended to Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, and Greater London (with differing powers), with London being the only English region to have significantly devolved power.

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 (Home Rule Act) is regarded as the beginning of devolution in the United Kingdom, granting Ireland home rule as a constituent country of the United Kingdom. After the partition of Ireland in 1921, Northern Ireland retained the Parliament of Northern Ireland. However Northern Ireland was later put under direct rule and its Parliament suspended during the Troubles.

Key events and modern examples concerning devolution include the Scottish devolution referendum of 1997, Welsh devolution referendum of 1997 and the 1998 Belfast Agreement (Good Friday Agreement). All of these events have ensured that three of the four constituent countries now, to a certain extent, have autonomy. However, there is still the question of England, which, unlike Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, does not have its own legislative body and is governed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom. This has caused for critics to bring up the English question, which concerns whether non-English Members of the House of Commons should be able to vote on matters concerning only England.

A federal government was proposed in 1912 by Winston Churchill, Member of Parliament for Dundee, with the idea that English regions should be governed by regional parliament, noting areas such as Lancashire, Yorkshire, the Midlands and London.[2][3]

Context[]

Union of the crowns[]

English monarchs have had varying clout around the Isles since the Norman Era; conquering Wales and parts of Ireland; Wars in Scotland. Nonetheless, the kingdoms remained separate entities aside from the Principality of Wales being annexed to England in the 16th century. However, in 1603 Queen Elizabeth I of England died childless, meaning that the crown of England passed to James VI of Scotland, her first cousin twice removed, who became James I of England. Whilst England and Scotland remained in a personal union with the same head of state, they remained sovereign states with parliaments and institutions separate of each other's. England and Scotland were briefly united under a republic after the War of the Three Kingdoms, but this was repealed after the restoration of Charles II. The 1707 Acts of Union however, passed by both the Parliaments of England and of Scotland put the Treaty of Union into effect, unifying the two kingdoms into the Kingdom of Great Britain with a single parliament (albeit with differing legal systems). The further Acts of Union 1800 unified the Kingdoms of Great Britain and of Ireland into the single United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland with a newly unified parliament.

20th Century[]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries Irish home rule was a divisive political issue. The First and Second Home Rule Bills failed to pass the UK Parliament. The Third Home Rule Bill was introduced in 1912 by Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, intended to provide home-rule in Ireland, with some additional proposals for home rule in Scotland, Wales, and areas of England.[2][3] The implementation of the Bill was however delayed by the outbreak of the First World War. At war's end the UK parliament, responding to Northern Irish Protestant lobbying, passed the Fourth Home Rule Bill which divided Ireland into a six county Northern Ireland and a twenty-six county Southern Ireland, each with its own parliament and judiciary. The Southern Parliament only met once: London acknowledged the sovereignty of southern Ireland as the Irish Free State, albeit within the British Commonwealth, at the end of 1921. The Northern Ireland Parliament remained until 1972 when it was abolished due to sectarian conflict in the Troubles.[1]

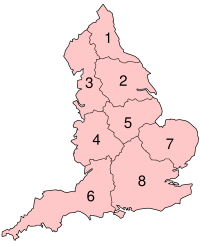

The 1966-1969 Redcliffe-Maud Report recommended the abolition of all existing two-tier councils & council areas in England and replacing them with 58 new unitary authorities alongside three metropolitan areas (Merseyside, 'Selnec', and the West Midlands). This would have been grouped into eight provinces with a provincial council each. Whilst the report was initially accepted "in principle" by the government,[4] after the 1970 General Election the plan was largely abandoned, although some proposals such as moving Slough into Berkshire and Bournemouth into Dorset were implemented in the 1974 local government reorganisation, and unitary authorities have become more commonplace since. In 1994, England was for statistical purposes divided into nine regions which were broadly similar county-by-county to the proposed provinces of Redcliffe-Maud, but with the notable addition of Greater London as a region of its own separate from South East England. As well as acting as European Parliamentary Constituencies, between 1994 and 2011 these regions had some devolved functions, for example in the case of regional chambers.

The 1998 Belfast Agreement established the Northern Ireland Assembly, based on power-sharing between the nationalist and unionist communities. Around the same time, the newly-elected Labour Government under Prime Minister Tony Blair held referenda in Scotland, Wales, and Greater London on devolved institutions. All the referenda were successful, leading to the creation of the Scottish Parliament, National Assembly for Wales, and Greater London Authority.

21st century[]

A further development in devolution was the 2004 North East England Devolution Referendum, which failed by a large margin. The original proposal was alongside planned referenda in North West England and Yorkshire and the Humber, but these were cancelled after the referendum in the North East failed.[5] The proposal, as well as facilitating an elected assembly, would have also reorganised local government in the area. After the failure of this proposal, the concept of city regions was later pursued. The 2009 Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act provided the means for the creation of combined authorities based upon city regions, a system providing cooperation between authorities, and a single directly elected mayor. The first such, the Greater Manchester Combined Authority, was established in 2011, followed by four in 2014, two in 2016, two in 2017, and one in 2018, with further proposals for other conurbations. In 2014, the Scotland voted to remain in the UK, though a plurality of Scots wanted greater autonomy within the UK.[6] This culminated in the Scotland Act of 2016 which declared that Scotland's devolved institutions were permanent and granted the Scottish Parliament and government powers over taxation and welfare.[7]

Proposals[]

England is by far the largest single unit in the United Kingdom by both population (84%) and area (54%),[8][1] which some argue would not effectively devolve were a single English parliament to exist.[9] This has prompted many proposals for a system based on smaller units.[10] The regions of England, created for statistical purposes, constitute one suggestion,[9] as seen with the 2004 North East England Devolution Referendum and with the existing Greater London Authority. Another suggestion has been on cultural regions based on the ancient Heptarchy.[11]

Regions (both formal and informal) which have had support for devolution include Yorkshire and Cornwall. The Yorkshire Party (formerly Yorkshire First) is a registered political party which promotes Yorkshire as a self-governing unit. The party stood 28 candidates in the 2019 General Election,[12] received 50,000 votes (3.9%) in the Yorkshire and the Humber constituency during the 2019 European Union Parliamentary Election, and has representation through local councillors.[13] This cause has also been supported by the cross-party One Yorkshire group of 18 local authorities (out of 20) in Yorkshire. One Yorkshire has sought the creation of a directly elected mayor of Yorkshire, devolution of decision-making to Yorkshire, and giving the county access to funding and benefits similar to combined authorities.[14] Various proposals differ between establishing this federal unit in Yorkshire and the Humber (which excludes parts of Yorkshire and includes parts of Lincolnshire), in the county of Yorkshire as a whole, or in parts of Yorkshire, with Sheffield and Rotherham each opting for a South Yorkshire Deal.[15][16] This has been criticised by proponents of the One Yorkshire solution, who have described it as a Balkanisation of Yorkshire and a waste of resources.[15] Cornwall has also been discussed as a potential area for further devolution and therefore a federal unit, particularly promoted by Mebyon Kernow. Cornwall has a distinct language and the Cornish have been recognised as a national minority within the United Kingdom, a status shared with Scots, Welsh and Irish.[17] The Wessex Regionalist Party has also promoted Wessex as a cultural region, but unlike the Yorkshire Party and Mebyon Kernow has not enjoyed any electoral success.

Support and opposition[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (March 2020) |

British federalism has had a varied history, with many different supporters of it. The Federal Union is a pressure group which supports a codified federal constitution for the United Kingdom, arguing that governance remains too centralised and that existing devolution remains "administrative rather than political".[18] Various politicians from across parties have also proposed federalism.[19][20]

Some have argued that the UK's decision to leave the European Union, which was widely supported in England and Wales but not in Scotland and Northern Ireland, has strengthened the Scottish independence movement and been problematic for the Good Friday Agreement.[21][22] As such, some have proposed federalism as a away of ensuring the Union continues.[23]

Party policy[]

National Parties[]

Regional Parties[]

- Scotland:

- Wales:

See also[]

- 1997 Scottish devolution Referendum

- 1997 Welsh devolution referendum

- 1998 Greater London Authority referendum

- 2004 North East England devolution referendum

- 2011 Welsh devolution referendum

- Asymmetric federalism

- Devolution in the United Kingdom

- Devolved English parliament

- Good Friday Agreement

- Historic counties of England

- Imperial Federation

- London independence

- NUTS statistical regions of the United Kingdom

- Regions of England

- Unionism in the United Kingdom

References[]

- ^ a b c "The big read: Can federalism ever work in the UK?". HeraldScotland. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ a b "Local Parliaments For England. Mr. Churchill's Outline Of A Federal System, Ten Or Twelve Legislatures". The Times. 13 September 1912.

- ^ a b "Mr. Winston Churchill's speech at Dundee". The Spectator. 14 September 1912.

- ^ Wood (1976). Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "Federalism provides a desirable path forward for the UK's constitution – and may be the only means of preserving the Union". Democratic Audit. 2016-06-10. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ "Scots back independence – but at a price, survey finds". The Guardian. 2011-12-05. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ "A Powerhouse Parliament? An Enduring Settlement? The Scotland Act 2016". The Edinburgh Law Review. 20 (3): 360–61. 2016. doi:10.3366/elr.2016.0367. Retrieved 28 January 2021 – via HeinOnline.

- ^ "Population estimates - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ a b editor. "A Federalist Constitution for the U.K." Federal Union. Retrieved 2020-03-05.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Quentin Peel (29 September 2014). "Federalism fit for a kingdom". Financial Times. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ "Now devolution is back in the headlines, why stop at Scotland?". Renew Party. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ "Party unveils 28 General Election candidates". Yorkshire Party - building a stronger Yorkshire in a fairer UK. 2019-11-14. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ "Devolution". Yorkshire Party - building a stronger Yorkshire in a fairer UK. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ Services, Web. "One Yorkshire devolution". City of York Council. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ a b "Government rejects Yorkshire devolution". BBC News. 2019-02-12. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ "West Yorkshire devolution deal could be signed by March as Ministers start formal talks with local leaders". www.yorkshirepost.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ "Cornish people are formally declared a national minority". The Independent. 2014-04-23. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ Richard. "Devolution". Federal Union. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ editor, Rowena Mason Deputy political (2020-01-26). "Keir Starmer: only a federal UK 'can repair shattered trust in politics'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-03-03.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "Our Constitution". Liberal Democrats. 2014-02-14. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ editor, Severin Carrell Scotland (2020-02-04). "Scottish independence surveys 'show Brexit has put union at risk'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-03-12.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "Good Friday Agreement: why it matters in Brexit". UK in a changing Europe. 2018-04-18. Retrieved 2020-03-12.

- ^ "Former Brexit chief urges rethink of UK Union". BBC News. 2019-09-09. Retrieved 2020-03-12.

- ^ "The Creation of a Federal United Kingdom". libdems.org.uk. 26 September 2020.

- ^ "Scot Lib Dems launch Federalism drive". scotlibdems.org.uk. 6 March 2017.

- ^ "Scottish Labour commits to federalism as Dugdale reaffirms support for Union". labourlist.org. 25 February 2017.

- ^ "Independence - Not the time, Not the Priority". welshlibdems.wales. 25 September 2020.

External links[]

- Devolution in the United Kingdom

- Federalism by country

- Political movements in the United Kingdom