Florence Augusta Merriam Bailey

Florence Augusta Merriam Bailey | |

|---|---|

Florence Merriam, 1904, Portrait from The Condor | |

| Born | Florence Augusta Merriam August 8, 1863 |

| Died | September 22, 1948 (aged 85) |

| Resting place | Locust Grove, New York, United States |

| Nationality | USA |

| Alma mater | Smith College (attended, 1882–1886; awarded, 1921), Stanford University |

| Known for | First modern field guide for birdwatchers, regional ornithology, bird conservation |

| Spouse(s) | Vernon Orlando Bailey |

| Awards | Brewster Medal |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Ornithology |

Florence Augusta Merriam Bailey (August 8, 1863 – September 22, 1948) was an American ornithologist and nature writer who has been referred to as the "First Lady of ornithology".[1] She organized early Audubon Society chapters and was an activist for bird protection.

She wrote extensively on birds for both a general and a scholarly audience. Her first published book Birds Through an Opera-Glass (1890) is considered the first bird field guide in the modern tradition. She followed it with other popular accounts.[1] She carried out extensive field work throughout the American West, often in collaboration with her husband Vernon Bailey, who specialized in mammalogy. Her field work was documented in several books, chief among them the important field guide Handbook of Birds of the Western United States (1902) and "her most important contribution to the ornithological literature", The Birds of New Mexico (1928), for which she was awarded the Brewster Medal.[2]

Life and work[]

Early life and family[]

Florence Augusta Merriam was born on August 8, 1863 in Locust Grove in Lewis County near Leyden, New York.[3][4] Her parents were Clinton Levi Merriam and Caroline Hart Merriam.[5] Florence's three older siblings were her brother Clinton Hart Merriam (known as C. Hart to distinguish him from his father), sister Ella Gertrude (who died before Florence was born), and brother Charles Collins.[6] Florence grew up at her family's estate, "Homewood", on a wooded hilltop above her grandparents' home at Locust Grove.[1][7]

Florence's father was interested in scientific matters and was in correspondence with John Muir after he had met him at Yosemite in the summer of 1871.[8] Florence and her brother C. Hart (almost eight years her senior) were encouraged to study natural history and astronomy by their mother, father, and aunt ; both of them became interested in ornithology at an early age.[9] When she was 9 years old, Florence accompanied her father and older brother to Florida on a two-month collecting trip.[1]

In her adolescence, Florence Merriam's health was somewhat fragile. She studied at Mrs. Piatt's private school in Utica, New York as a preparation for college.[10] Beginning in 1882, she attended Smith College as a special student, free to choose her own courses rather than following a set program. As a result she received a certificate rather than a degree when she graduated with the class of 1886.[11][12] She also attended six months of lectures at Stanford University in the winter of 1893–1894.[13][14][15] In 1921, Smith College recognized her candidacy for a degree and awarded her a bachelor's of arts.[16][13]

On a spring vacation from college, her family first made the acquaintance of Ernest Thompson Seton.[17] In 1884, Seton was invited to join the American Ornithologists' Union by C. Hart Merriam, who also invited Seton to visit him in upstate New York.[18] Seton encouraged Florence in her preference for studying birds in life.[17] In 1885, Florence Merriam too joined the American Ornithologists' Union, after being nominated by her brother C. Hart Merriam. She was the OAU's first woman associate member.[19]

The Merriam family, including Florence, often spent the more severe winters away from Homewood, in the milder climate of New York City.[20] In the winter, Florence worked with Grace Hoadley Dodge's Working Girls Society in New York City. During the summer of 1891 she taught working girls about birds in a program associated with Jane Addams's settlement work at Hull House.[1]

Both Florence and her mother Caroline may have had tuberculosis. They made a number of trips that are consistent with medical knowledge of their time.[21][4][2][1] Tuberculosis was the leading cause of death in the United States in the 1800s. Before the development of vaccines and antibiotics, tubercular patients had few options. Doctors often recommended a change of climate to drier, higher, sunnier locales. Although the mechanism of the disease was not understood, fresh air did help to prevent TB's transmission, and high altitude slowed the spreading of the bacteria within the lungs.[22] Caroline Hart Merriam died of tuberculosis on March 28, 1893.[23] It is likely that Florence also suffered from tuberculosis,[21][4] although her illness was never formally diagnosed as such.[24]

Activism to protect birds[]

At the time that Merriam became interested in birds, most bird study was based on collections and skins; however, she was more interested in studying living birds and their behavior in the field.[25] Also at this time, it was fashionable among women to wear bird feathers on their hats. Repulsed by this custom, in 1885, Merriam wrote the first of several newspaper articles arguing against the practice.[26] In 1886, in collaboration with the like-minded George Bird Grinnell and classmate Fannie Hardy, she organized the Smith College Audubon Society (SCAS), a local chapter of Grinnell's nascent National Audubon Society.[27] The SCAS invited naturalist John Burroughs to visit, and in 1886 he participated in the first of a series of nature walks with the group.[28][1]

Once she moved to Washington, Merriam helped organize the Audubon Society of the District of Columbia in 1897, and she began teaching bird classes for that organization the following year.[29] Meanwhile, she became active with the Committee on Bird Protection of the American Ornithologists' Union.[30] In part due to her influence, the practice of ornithology moved away from the study of dead birds to that of living ones.[31]

She was dedicated to showing and telling people about the value of living birds, and continued to work for their protection. As a result of her efforts and others', the Lacey Act of 1900 prohibited interstate trade in wildlife that had been illegally taken, transported or sold. This was a first step in stopping the slaughter and decreasing the number of victims, especially among seabirds such as pelicans and grebes.[32] Eventually, more legislation, changing styles, and continued education stopped the killing of birds for hat decoration and clothing.[33][34]

Field and regional ornithology[]

Florence Merriam's introduction of a birdwatching field guide, focused on living birds observed in the field, is considered the first in the tradition of modern, illustrated bird guides. She published Birds Through an Opera-Glass (1890) at the age of 26, adapting a series of notes that she had previously published in George Bird Grinnell's The Audubon Magazine. Florence's first book described 70 common species[35] and focused on the areas where Florence had grown up and studied, her "home ground".[1] Directed at women and young people, the work has been described as "charming, unpretentious, and useful."[21]

In 1889, before the book appeared in print, Florence made the first of many voyages farther field through the western United States. She and her family visited her uncle, Major , at his homestead in San Diego County, California, called "Twin Oaks".[36] One purpose of the trip was the restoration of Florence's health, a recurrent concern in her early travels.[21][4]

After her mother's death in 1893, Florence returned to the West, this time visiting Utah and Arizona in the company of Olive Thorne Miller. She described these experiences in My Summer in a Mormon Village (1894). Unlike her other bird-oriented writing, this book was a travel narrative.[37][1]

Her second trip to Twin Oaks, where she studied birds, mounted on horseback, resulted in the publication of A-Birding on a Bronco (1896).[38] (This was the first book to be illustrated by Louis Agassiz Fuertes.[39]) On her return from the west, Florence made her home with her brother C. Hart in Washington, D.C., where she worked to organize local chapters of the Women's National Science Club.[40]

In Birds of Village and Field (1898), Merriam expanded the scope of her popular bird guide to more than 150 species. Once again, the book was intended for the beginner.[41] Illustrations for the book were drawn by Ernest Thompson Seton, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, and John L. Ridgway.[1]

"Four things only are necessary — a scrupulous conscience, unlimited patience, a notebook, and an opera-glass. The notebook enables one to put down the points which the opera-glass has brought within sight, and by means of which the bird may be found in the key; patience leads to trained ears and eyes, and conscience prevents hasty conclusions and doubtful records." Florence Merriam, Birds of village and field (1898)[42]

On December 18, 1899, Florence Augusta Merriam married Vernon Orlando Bailey, Chief Field Naturalist for the United States Bureau of Biological Survey and a long-time colleague of C. Hart's.[43][1] They eventually built a home at 1834 Kalorama Road, N.W., in the Adams Morgan neighborhood of Washington.[44][45] Among the visitors to the Baileys' home were the naturalist-turned-inventor Clarence Birdseye[46] and the botanist Alice Eastwood.[47] The wildlife artist Charles R. Knight provided the centerpiece of the home's library, a painted portrait of a tiger in repose.[48] The Baileys befriended the young naturalist couple Olaus Murie and Margaret "Mardy" Murie, and they became regular guests at the Washington residence.[49] The couple were together responsible for encouraging many youngsters take up studies in natural history.[50]

The naturalist couple traveled extensively, generally spending the spring and summer camping somewhere in the west and returning to Washington, D.C. in the fall. Their first trek together, from Corpus Christi, Texas to Brownsville, Texas, took place in April 1900. They covered 260 miles in 17 days, driven in a carriage by a "camp man" who also set up tents and cooked meals. Along with the many specimens that they collected and photographed on this trip, they discovered a new species of epiphytic plant.[1]

With the publication of Handbook of Birds of the Western United States (1902), Florence moved from writing for the general enthusiast to a scholarly audience. Her new book was a major work of ornithology and a complement to Frank Chapman's Handbook of birds of eastern North America (1895). Florence Merriam Bailey's achievement drew on the best available published work, study of specimens with the assistance of Robert Ridgway of the Smithsonian Institution, 600 illustrations from numerous sources, and her own field work.[51] The book would remain a standard reference for the study of regional ornithology for at least 50 years.[44] Without sacrificing technical precision, the handbook included vivid descriptions of behaviors like nesting, feeding, and vocalization, information that has been de-emphasized in the literature that followed.[52]

Beginning in 1903, the Baileys carried out substantial research in the field in what was then New Mexico Territory. For the next three summers, they crisscrossed the region.[53]

During the next three decades, Florence and Vernon covered much of the American West. They explored southern California in 1907,[54] North Dakota in 1909, 1912, and 1916,[55] coastal Oregon in 1914,[56] and Glacier National Park in 1917.[56] Florence published 17 papers over 5 years about prairie birds in the journal The Condor, and another series about Oregon's forest, mountain and sea-birds.[2] She also wrote for The Auk, Bird-lore and its successor Audubon Magazine.[44] The results of the Bailey's field work in Glacier Park was published jointly as Wild Animals of Glacier National Park (1918).[57]

After the death of Wells Cooke in 1916, Florence was asked by Edward William Nelson if she would take Cooke's notes and complete a work on New Mexico's bird life. She substsntially updated and expanded Cooke's data, creating a "monumental work".[2][1] The extent of her contribution was recognized by her being credited with sole authorship of the completed work; Cook's initial contribution is recognized in the introduction. With 24 color plates and numerous drawings and photographs,[2] The Birds of New Mexico is considered her magnum opus.[58] Completed in 1919, it took another 9 years to raise the money to have it printed. The Birds of New Mexico was finally published by the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish in 1928.[2] Florence's accomplishment was recognized with her appointment as the first woman fellow of the American Ornithologists' Union in 1929,[59][2] and with the Brewster Medal in 1931.[60][2]

Florence had visited the Arizona Territory in the 1890s;[61] as a couple or alone, Florence returned for field work in what was now the State of Arizona several times during the 1920s.[1][62] Her last published work was Among the Birds in the Grand Canyon Country, published by the National Park Service in 1939, ten years before her death.[63]

Despite the energetic activity that she and her husband pursued, traveling cross country and hiking and packing everywhere, Florence Merriam Bailey's approach to the study of nature was one of gentle, quiet contemplation. She wrote, "Cultivate a philosophic spirit, be content to sit and listen to the voices of the marsh; let the fascinating, mysterious, bewildering voices encompass you and—hold your peace."[64]

Later life and death[]

Florence Merriam Bailey died of myocardial degeneration in Washington, D.C., on September 22, 1948. She is buried at the old Merriam home in Locust Grove, New York.[13][31]

In a memorial essay, Paul Oehser favorably compared Florence Merriam Bailey's early books to the writing of Muir and Burroughs, and he described her as "one of the most literary ornithologists of her time, combining an intense love of birds and remarkable powers of observation with a fine talent for writing and a high reverence for science."[65]

Some of Florence Merriam Bailey's papers, including diaries, photographs and field books, are held by the Smithsonian Institution Archives.[66][67]

Affiliations and recognition[]

Bailey became the first woman associate member of the American Ornithologists' Union in 1885 (nominated by her brother C. Hart),[19] its first woman fellow in 1929,[59] and the first woman recipient of its Brewster Medal in 1931, awarded for Birds of New Mexico.[68] In 1933, she received an honorary LL.D. degree from the University of New Mexico.[69]

She was a founding member of the Audubon Society of the District of Columbia and frequently led its classes in basic ornithology. In 1908, Joseph Grinnell named a California subspecies of mountain chickadee in her honor.[70] Recent mtDNA cytochrome b sequence data and morphology suggest that the mountain chickadee is more accurately placed in the genus Poecile rather than Parus.[71]

In 1992, a mountain in the southern Oregon Cascade Range was named Mount Bailey, in honor of Florence and Vernon Bailey, by the Oregon Geographic Names Board.[72]

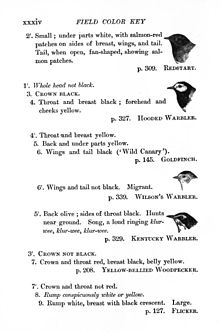

Sample illustrations[]

Sample illustrations from some of Florence Merriam Bailey's books.

Nest of the Bush-tit

Valley Quail and Road-Runner

Chimney swifts

Western robin, during the nesting season

Selected publications[]

| Library resources about Florence Augusta Merriam Bailey |

| By Florence Augusta Merriam Bailey |

|---|

- Merriam, Florence A. (1890). Birds Through an Opera-Glass. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.60311.

- Merriam, Florence A. (1894). My Summer in a Mormon Village. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- Merriam, Florence A. (1896). A-Birding on a Bronco. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.12539.

- Merriam, Florence A. (1896). How Birds Affect the Farm and Garden. New York, NY: Forest and Stream Publishing. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.36220.

- Merriam, Florence A. (1898). Birds of Village and Field: A Bird Book for Beginners. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.30028.

- Bailey, Florence Merriam (1902). Handbook of Birds of the Western United States, Including the Great Plains, Great Basin, Pacific Slope, and Lower Rio Grande Valley. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.7872. Plates by Louis Agassiz Fuertes.

- Bailey, Vernon; Bailey, Florence Merriam (1918). Wild Animals of Glacier National Park. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.13645..

- Bailey, Florence Merriam (1928). Birds of New Mexico. Santa Fe, NM: New Mexico Dept. of Game and Fish in cooperation with the State Game Protective Association and the Bureau of Biological Survey. hdl:2027/mdp.39015019729311. "With Contributions by the Late Wells Woodbridge Cooke... Illustrated with Colored Plates by Allan Brooks, Plates and Text Figures by the Late Louis Agassiz Fuertes."

- Bailey, Florence Merriam (1939). Among the Birds in the Grand Canyon Country. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Bonta, Marcia Myers (April 1, 1991). "Florence Merriam Bailey, first lady of ornithology". Women in the Field: America's Pioneering Women Naturalists. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. pp. 186–196. ISBN 978-0890964897.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Creese, Mary R. S. (2000-01-01). Ladies in the Laboratory? American and British Women in Science, 1800-1900: A Survey of their Contributions to Research. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780585276847.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 7417, Bailey, Florence Merriam, 1863, Florence Merriam Bailey Papers

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Welker, Robert H. (1950). "Bailey, Florence Augusta Merriam". In Garraty, John A.; James, Edward T. (eds.). Dictionary of American Biography. Supplement Four. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 41–42.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 5–6.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 7–11.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Oehser (1952), p. 19.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 3–11.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 20–21.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 23,39.

- ^ Smith, Shearer, Barbara; F., Shearer, Benjamin (1996-01-01). Notable women in the life sciences : a biographical dictionary. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313293023. OCLC 832549823.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Oehser (1971).

- ^ Richard H. Cracroft and Neal E. Lambert. A Believing People (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1974) p. 87

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 60–61.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 155.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kofalk (1989), p. 26.

- ^ Sterling, Keir B. "Ernest Thompson Seton (14 Aug 1860 - 23 Oct 1946)". TODAY IN SCIENCE HISTORY. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kofalk (1989), p. 29.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 40,53.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Oehser (1952), p. 20.

- ^ Blakemore, Erin (April 24, 2020). "The Disease That Helped Put Colorado on the Map". This Day in History. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Caroline Hart Merriam (1827-1893)". Find A Grave Memorial. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 46.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 11.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 31,205.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 34–35.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 36–37.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 81.

- ^ Dutcher, William (1898). "Report of the Committee on Bird Protection". The Auk. 15 (1): 81–114. doi:10.2307/4068463. JSTOR 4068463.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wolfe, Jonathan (July 17, 2019). "Overlooked No More: Florence Merriam Bailey, Who Defined Modern Bird-Watching". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 90.

- ^ Birdsall, Amelia (2002). A woman's nature : attitudes and identities of the bird hat debate at the turn of the 20th Century. Haverford, PA: Haverford College. Department of History. hdl:10066/675. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Serratore, Angela (May 15, 2018). "Keeping Feathers Off Hats–And On Birds". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Barrow, Mark V. (1998). A Passion for Birds: American Ornithology after Audubon. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 156–157. ISBN 9780691044026.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 46–48.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 55.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 63–65.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 77.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 73.

- ^ Dunlap, Thomas R. (2011). In the Field, Among the Feathered: A History of Birders & Their Guides. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780199734597.

- ^ Merriam, Florence (1898). Birds of village and field: a bird book for beginners. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and company. pp. viii–ix. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 87.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Oehser (1952), p. 22.

- ^ "Florence Bailey". DC Writers’ Homes. 28 November 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ Oehser (1952), p. 23.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 116.

- ^ Oehser (1952), p. 24.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 143,158,161.

- ^ Oehser (1952).

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 103–104.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 104.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 111–112.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 119.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 130, 133.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kofalk (1989), p. 138.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 143.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 146.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Palmer, T. S. (April 1930). "The Forty-Seventh Stated Meeting of the American Ornithologists' Union, October 21-24, 1929" (PDF). The Auk. 47 (2): 219. doi:10.2307/4075926. JSTOR 4075926. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ "William Brewster Memorial Award". American Ornithologists Society. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 72.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), pp. 149,170.

- ^ "Florence Merriam Bailey." Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed., vol. 1, Gale, 2004, pp. 443-444. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX3404700387/GVRL?u=albu78484&sid=GVRL&xid=78539630. Accessed 16 May 2019.

- ^ Bailey, Florence Merriam (January 1916). "Characteristic Birds of the Dakota Prairies: III. Among the Sloughs and Marshes". The Condor. 18 (1): 14–21. doi:10.2307/1362890. JSTOR 1362890. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ Oehser (1952), p. 21.

- ^ "The Florence Merriam Bailey Photograph Collection and Finding Aid". Smithsonian Archives. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Field books from California and Maine". Biodiversity Heritage Library. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Palmer, T. S. (January 1932). "The Forty-Ninth Stated Meeting of the American Ornithologists' Union, October 19-22, 1931" (PDF). The Auk. 49 (1): 52–64. doi:10.2307/4076702. JSTOR 4076702. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Kofalk (1989), p. 168.

- ^ Oehser (1952), p. 26.

- ^ Gill, Frank B.; Slikas, Beth; Sheldon, Frederick H. (2005). "Phylogeny of titmice (Paridae): II. Species relationships based on sequences of the mitochondrial cytochrome-b gene". Auk. 122: 121–143. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2005)122[0121:POTPIS]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Contreras, Alan. "Florence Augusta Merriam Bailey". The Oregon Encyclopedia.. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

Bibliography[]

- Kofalk, Harriet (1989). No Woman Tenderfoot: Florence Merriam Bailey, Pioneer Naturalist. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-378-4.

- Oehser, Paul H. (1952). "In Memoriam: Florence Merriam Bailey" (PDF). The Auk. 69 (1): 19–26. doi:10.2307/4081288. JSTOR 4081288. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Oehser, Paul H. (1971). "Bailey, Florence Augusta Merriam". In James, Edward T.; James, Janet Wilson; Boyer, Paul S. (eds.). Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary. I. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 82–83.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Florence Augusta Merriam Bailey. |

- Works by Florence A. Merriam at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Florence Augusta Merriam Bailey at Internet Archive

- Works by Florence Augusta Merriam Bailey at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Florence Merriam Bailey Photograph Collection and Finding Aid from the Smithsonian Institution Archives

- Field books from California and Maine in the Biodiversity Heritage Library

- American ornithologists

- Women ornithologists

- Smith College alumni

- Stanford University alumni

- 1863 births

- 1948 deaths

- American nature writers

- American women scientists

- Writers from New York (state)