Frank Capra

Frank Capra | |

|---|---|

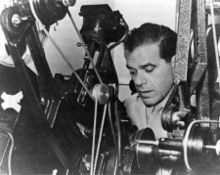

Capra c. 1930s | |

| Born | Francesco Rosario Capra May 18, 1897 |

| Died | September 3, 1991 (aged 94) La Quinta, California, U.S. |

| Burial place | Coachella Valley Public Cemetery |

| Other names | Frank Russell Capra |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | California Institute of Technology |

| Occupation | Film director, producer, writer |

| Years active | 1922–1964 |

| Title | President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences 1935–1939 |

| Political party | Republican[1] |

| Spouse(s) | Helen Howell

(m. 1923; div. 1928)Lucille Warner

(m. 1932; died 1984) |

| Children | 4, including Frank Jr. |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1918 1941–1945[2] |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | Army Signal Corps[3][4] |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Medal Legion of Merit World War I Victory Medal American Defense Service Medal American Campaign Medal World War II Victory Medal |

Frank Russell Capra (born Francesco Rosario Capra; May 18, 1897 – September 3, 1991) was an Italian-born American film director, producer and writer who became the creative force behind some of the major award-winning films of the 1930s and 1940s. Born in Italy and raised in Los Angeles from the age of five, his rags-to-riches story has led film historians such as Ian Freer to consider him the "American Dream personified".[5]

Capra became one of America's most influential directors during the 1930s, winning three Academy Awards for Best Director from six nominations, along with three other Oscar wins from nine nominations in other categories. Among his leading films were It Happened One Night (1934), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), You Can't Take It with You (1938), and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939). During World War II, Capra served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps and produced propaganda films, such as the Why We Fight series.[3][4]

After World War II, Capra's career declined as his later films, such as It's a Wonderful Life (1946), performed poorly when they were first released.[6] In ensuing decades, however, It's a Wonderful Life and other Capra films were revisited favorably by critics. Outside of directing, Capra was active in the film industry, engaging in various political and social activities. He served as President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, worked alongside the Writers Guild of America, and was head of the Directors Guild of America.

Early life[]

Capra was born Francesco Rosario Capra in Bisacquino, a village near Palermo, Sicily, Italy. He was the youngest of seven children of Salvatore Capra, a fruit grower, and the former Rosaria "Serah" Nicolosi. Capra's family was Roman Catholic.[7] The name "Capra", notes Capra's biographer Joseph McBride, represents his family's closeness to the land, and means "goat".[8] He notes that the English word "capricious" derives from it, "evoking the animal's skittish temperament", adding that "the name neatly expresses two aspects of Frank Capra's personality: emotionalism and obstinacy."[8]

In 1903, when he was five, Capra's family emigrated to the United States, traveling in a steerage compartment of the steamship Germania,-- the cheapest way to make the passage. For Capra the journey, which took 13 days, remained one of the worst experiences of his life:

You're all together—you have no privacy. You have a cot. Very few people have trunks or anything that takes up space. They have just what they can carry in their hands or in a bag. Nobody takes their clothes off. There's no ventilation, and it stinks like hell. They're all miserable. It's the most degrading place you could ever be.[9]

Capra remembers the ship's arrival in New York Harbor, where he saw "a statue of a great lady, taller than a church steeple, holding a torch above the land we were about to enter". He recalls his father's exclamation at the sight:

Ciccio, look! Look at that! That's the greatest light since the star of Bethlehem! That's the light of freedom! Remember that

— Freedom.[10]

The family settled in Los Angeles's East Side (today Lincoln Heights) on avenue 18, which Capra described in his autobiography as an Italian "ghetto".[11] Capra's father worked as a fruit picker and young Capra sold newspapers after school for 10 years, until he graduated from high school. Instead of working after graduating, as his parents wanted, he enrolled in college. He worked through college at the California Institute of Technology, playing banjo at nightclubs and taking odd jobs like working at the campus laundry facility, waiting tables, and cleaning engines at a local power plant. He studied chemical engineering and graduated in the spring of 1918.[12] Capra later wrote that his college education had "changed his whole viewpoint on life from the viewpoint of an alley rat to the viewpoint of a cultured person".[13]

World War I and later[]

Soon after graduating from college, Capra was commissioned in the United States Army as a second lieutenant, having completed campus ROTC. In the Army, he taught mathematics to artillerymen at Fort Point, San Francisco. His father died during the war in an accident (1916). In the Army, Capra contracted Spanish flu and was medically discharged to return home to live with his mother. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1920, taking the name Frank Russell Capra.[13] Living at home with his siblings and mother, Capra was the only family member with a college education, yet he was the only one who remained chronically unemployed. After a year without work, seeing how his siblings had steady jobs, he felt he was a failure, which led to bouts of depression.[13]

Chronic abdominal pains were later discovered to have been an undiagnosed burst appendix.[13] After recovering at home, Capra moved out and spent the next few years living in flophouses in San Francisco and hopping freight trains, wandering the Western United States. To support himself, he took odd jobs on farms, as a movie extra, playing poker, and selling local oil well stocks.

During this time the 24-year-old Capra directed a 32-minute documentary film titled La Visita Dell'Incrociatore Italiano Libya a San Francisco. Not only did it document the visit of the Italian naval vessel Libya to San Francisco, but also the reception given to the crew of the ship by San Francisco's L'Italia Virtus Club, now known as the San Francisco Italian Athletic Club.

At 25, Capra took a job selling books written and published by American philosopher Elbert Hubbard.[13] Capra recalled that he "hated being a peasant, being a scrounging new kid trapped in the Sicilian ghetto of Los Angeles. ... All I had was cockiness—and let me tell you that gets you a long way."[14]

Career[]

Silent film comedies[]

During his book sales efforts—and nearly broke—Capra read a newspaper article about a new movie studio opening in San Francisco. Capra phoned them saying he had moved from Hollywood, and falsely implied that he had experience in the budding film industry. Capra's only prior exposure in films was in 1915 while attending Manual Arts High School. The studio's founder, Walter Montague, was nonetheless impressed by Capra and offered him $75 to direct a one-reel silent film. Capra, with the help of a cameraman, made the film in two days and cast it with amateurs.[13]

After that first serious job in films, Capra began efforts to finding similar openings in the film industry. He took a position with another minor San Francisco studio and subsequently received an offer to work with producer Harry Cohn at his new studio in Los Angeles. During this time, he worked as a property man, film cutter, title writer, and assistant director.[15]

Capra later became a gag writer for Hal Roach's Our Gang series. He was twice hired as a writer for a slapstick comedy director, Mack Sennett, in 1918 and 1924.[16] Under him, Capra wrote scripts for comedian Harry Langdon and produced by Mack Sennett, the first being Plain Clothes in 1925. According to Capra, it was he who invented Langdon's character, the innocent fool living in a "naughty world"; however, Langdon was well into this character by 1925.[15]

When Langdon eventually left Sennett to make longer, feature-length movies with First National Studios, he took Capra along as his personal writer and director. They made three feature films together during 1926 and 1927, all of them successful with critics and the public. The films made Langdon a recognized comedian in the caliber of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. Capra and Langdon later had a falling out, and Capra was fired. During the following years, Langdon's films went into decline without Capra's assistance.[17] After splitting with Langdon, Capra directed a picture for First National, For the Love of Mike (1927). This was a silent comedy about three bickering godfathers—a German, a Jew, and an Irishman—starring a budding actress, Claudette Colbert. The movie was considered a failure and is a lost film.[15]

Columbia Pictures[]

Capra returned to Harry Cohn's studio, now named Columbia Pictures, which was then producing short films and two-reel comedies for "fillers" to play between main features. Columbia was one of many start-up studios on "Poverty Row" in Los Angeles. Like the others, Columbia was unable to compete with larger studios, which often had their own production facilities, distribution, and theaters. Cohn rehired Capra in 1928 to help his studio produce new, full-length feature films, to compete with the major studios. Capra would eventually direct 20 films for Cohn's studio, including all of his classics.[15]

Because of Capra's engineering education, he adapted more easily to the new sound technology than most directors. He welcomed the transition to sound, recalling, "I wasn't at home in silent films."[15] Most studios were unwilling to invest in the new sound technology, assuming it was a passing fad. Many in Hollywood considered sound a threat to the industry and hoped it would pass quickly; McBride notes that "Capra was not one of them." When he saw Al Jolson singing in The Jazz Singer in 1927, considered the first talkie, Capra recalled his reaction:

It was an absolute shock to hear this man open his mouth and a song come out of it. It was one of those once-in-a-lifetime experiences.[18]

Few of the studio heads or crew were aware of Capra's engineering background until he began directing The Younger Generation in 1929. The chief cinematographer who worked with Capra on a number of films was likewise unaware. He describes this early period in sound for film:

It wasn't something that came up. You had to bluff to survive. When sound first came in, nobody knew much about it. We were all walking around in the dark. Even the sound man didn't know much about it. Frank lived through it. But he was quite intelligent. He was one of the few directors who knew what the hell they were doing. Most of your directors walked around in a fog – —they didn't know where the door was.[19]

During his first year with Columbia, Capra directed nine films, some of which were successful. After the first few, Harry Cohn said: "it was the beginning of Columbia making a better quality of pictures."[20] According to Barson, "Capra became ensconced as Harry Cohn's most trusted director."[21] His films soon established Capra as a "bankable" director known throughout the industry, and Cohn raised Capra's initial salary of $1,000 per film to $25,000 per year.[15] Capra directed a film for MGM during this period, but soon realized he "had much more freedom under Harry Cohn's benevolent dictatorship", where Cohn also put Capra's "name above the title" of his films, a first for the movie industry.[22] Capra wrote of this period and recalled the confidence that Cohn placed in Capra's vision and directing:

I owed Cohn a lot—I owed him my whole career. So I had respect for him, and a certain amount of love. Despite his crudeness and everything else, he gave me my chance. He took a gamble on me.[23]

Capra directed his first "real" sound picture, The Younger Generation, in 1929. It was a rags-to-riches romantic comedy about a Jewish family's upward mobility in New York City, with their son later trying to deny his Jewish roots to keep his rich, gentile girlfriend.[24] According to Capra biographer Joseph McBride, Capra "obviously felt a strong identification with the story of a Jewish immigrant who grows up in the ghetto of New York ... and feels he has to deny his ethnic origins to rise to success in America." Capra, however, denied any connection of the story with his own life.[25]

Nonetheless, McBride insists that The Younger Generation abounds with parallels to Capra's own life. McBride notes the "devastatingly painful climactic scene", where the young social-climbing son, embarrassed when his wealthy new friends first meet his parents, passes his mother and father off as house servants. That scene, notes McBride, "echoes the shame Capra admitted feeling toward his own family as he rose in social status".[26]

During his years at Columbia, Capra worked often with screenwriter Robert Riskin (husband of Fay Wray), and cameraman Joseph Walker. In many of Capra's films, the wise-cracking and sharp dialogue was often written by Riskin, and he and Capra went on to become Hollywood's "most admired writer-director team".[27]

Film career (1934–1941)[]

It Happened One Night (1934)[]

Capra's films in the 1930s enjoyed immense success at the Academy Awards. It Happened One Night (1934) became the first film to win all five top Oscars (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Actress, and Best Adapted Screenplay). Written by Robert Riskin, it is one of the first of the screwball comedies, and with its release in the Great Depression, critics considered it an escapist story and a variation of the American Dream. The film established the names of Capra, Columbia Pictures, and stars Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert in the movie industry. The film has been called "picaresque". It was one of the earliest road movies and inspired variations on that theme by other filmmakers.[28]

He followed the film with Broadway Bill (1934), a screwball comedy about horse racing. The film was a turning point for Capra, however, as he began to conceive an additional dimension to his movies. He started using his films to convey messages to the public. Capra explains his new thinking:

My films must let every man, woman, and child know that God loves them, that I love them, and that peace and salvation will become a reality only when they all learn to love each other.[28]

This added goal was inspired after meeting with a Christian Scientist friend who told him to view his talents in a different way:

The talents you have, Mr. Capra, are not your own, not self-acquired. God gave you those talents; they are his gifts to you, to use for his purpose.[28]

Capra began to embody messages in subsequent films, many of which conveyed "fantasies of goodwill". The first of those was Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), for which Capra won his second Best Director Oscar. Critic Alistair Cooke observed that Capra was "starting to make movies about themes instead of people".[29]

In 1938, Capra won his third Director Oscar in five years for You Can't Take It with You, which also won Best Picture. In addition to his three directing wins, Capra received directing nominations for three other films (Lady for a Day, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and It's a Wonderful Life). On May 5, 1936, Capra hosted the 8th Academy Awards ceremony.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)[]

Although It's a Wonderful Life is his best-known film, Friedman notes that it was Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), which most represented the "Capra myth". That film expressed Capra's patriotism more than any others, and "presented the individual working within the democratic system to overcome rampant political corruption".[30]

The film, however, became Capra's most controversial. In his research before filming, he was able to stand close to President Franklin D. Roosevelt during a press conference after the recent acts of war by Germany in Europe. Capra recalls his fears:

And panic hit me. Japan was slicing up the colossus of China piece by piece. Nazi panzers had rolled into Austria and Czechoslovakia; their thunder echoed over Europe. England and France shuddered. The Russian bear growled ominously in the Kremlin. The black cloud of war hung over the chancelleries of the world. Official Washington from the President down, was in the process of making hard, torturing decisions. "And here was I, in the process of making a satire about government officials; ... Wasn't this the most untimely time for me to make a film about Washington?[31]

When the filming was completed, the studio sent preview copies to Washington. Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., U.S. ambassador to the UK, wrote to Columbia head Harry Cohn, "Please do not play this picture in Europe."[30] Politicians were concerned about the potential negative effect the film might have on the morale of the United States' allies, as World War II had begun. Kennedy wrote to President Roosevelt that, "In foreign countries this film must inevitably strengthen the mistaken impression that the United States is full of graft, corruption and lawlessness."[32] Many studio heads agreed, nor did they want negative feelings about Hollywood instilled in political leaders.[33]

Nonetheless, Capra's vision of the film's significance was clear:

The more uncertain are the people of the world, the more their hard-won freedoms are scattered and lost in the winds of chance, the more they need a ringing statement of America's democratic ideals. The soul of our film would be anchored in Lincoln. Our Jefferson Smith would be a young Abe Lincoln, tailored to the rail-splitter's simplicity, compassion, ideals, humor, and unswerving moral courage under pressure.[34]

Capra pleaded with Cohn to allow the film to go into distribution and remembers the intensity of their decision making:

Harry Cohn paced the floor, as stunned as Abraham must have been when the Lord asked him to sacrifice his beloved son Isaac.[35]

Cohn and Capra chose to ignore the negative publicity and demands and released the film as planned. It was later nominated for 11 Academy Awards, only winning one (for Best Original Story) partly because of the number of major pictures that were nominated that year was 10, including The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind.[21] Hollywood columnist Louella Parsons called it a "smash patriotic hit" and most critics agreed, seeing that audiences left the theaters with "an enthusiasm for democracy" and "in a glow of patriotism".[32]

The significance of the film's message was established further in France, shortly after World War II began. When the French public was asked to select which film they wanted to see most, having been told by the Vichy government that soon no more American films would be allowed in France, the overwhelming majority chose it over all others. To a France soon to be invaded and occupied by Nazi forces, the film most expressed the "perseverance of democracy and the American way".[30]

Meet John Doe (1941)[]

In 1941 Capra directed Meet John Doe (1941), which some consider Capra's most controversial movie. The film's hero, played by Gary Cooper, is a former baseball player now bumming around, lacking goals. He is selected by a news reporter to represent the "common man," to capture the imagination of ordinary Americans. The film was released shortly before America became involved in World War II, and citizens were still in an isolationist mood. According to some historians, the film was made to convey a "deliberate reaffirmation of American values," though ones that seemed uncertain with respect to the future.

Film author Richard Glazer speculates that the film may have been autobiographical, "reflecting Capra's own uncertainties". Glazer describes how, "John's accidental transformation from drifter to national figure parallels Capra's own early drifting experience and subsequent involvement in movie making ... Meet John Doe, then, was an attempt to work out his own fears and questions."[36]

World War II years (1941–1945)[]

Joining the Army after Pearl Harbor[]

Within four days after the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Capra quit his successful directing career in Hollywood and received a commission as a major in the United States Army. He also gave up his presidency of the Screen Directors Guild. Being 44 years of age, he was not asked to enlist, but, notes Friedman, "Capra had an intense desire to prove his patriotism to his adopted land."[30]

Capra recalls some personal reasons for enlisting:

I had a guilty conscience. In my films I championed the cause of the gentle, the poor, the downtrodden. Yet I had begun to live like the Aga Khan. The curse of Hollywood is big money. It comes so fast it breeds and imposes its own mores, not of wealth, but of ostentation and phony status.[37]

Why We Fight series[]

During the next four years of World War II, Capra's job was to head a special section on morale to explain to soldiers "why the hell they're in uniform", writes Capra, and were not "propaganda" films like those created by the Nazis and Japan. Capra directed or co-directed seven documentary war information films.

Capra was assigned to work directly under Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, the most senior officer in command of the Army, who later created the Marshall Plan and was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize. Marshall chose to bypass the usual documentary film-making department, Signal Corps, because he felt they were not capable of producing "sensitive and objective troop information films". One colonel explained the importance of these future films to Capra:

You were the answer to the General's prayer ... You see, Frank, this idea about films to explain "why" the boys are in uniform is General Marshall's own baby, and he wants the nursery right next to his Chief of Staff's office.[38]

During his first meeting with General Marshall, Capra was told his mission:

Now, Capra, I want to nail down with you a plan to make a series of documented, factual-information films—the first in our history—that will explain to our boys in the Army why we are fighting, and the principles for which we are fighting ... You have an opportunity to contribute enormously to your country and the cause of freedom. Are you aware of that, sir?[39]

The films included the seven-episode Why We Fight series – consisting of Prelude to War (1942),[40] The Nazis Strike (1942),[41] Divide and Conquer (1943), The Battle of Britain (1943), The Battle of Russia (1943), The Battle of China (1944), War Comes to America (1945) – plus Know Your Enemy: Japan (1945), Here Is Germany (1945), Tunisian Victory (1945), and Two Down and One to Go (1945) that do not bear the Why We Fight banner; as well as the African-American related film, The Negro Soldier (1944).[42]

After he completed the first few documentaries, government officials and U.S. Army staff felt they were powerful messages and excellent presentations of why it was necessary for the United States to fight in the war. All footage came from military and government sources, whereas during earlier years, many newsreels secretly used footage from enemy sources. Animated charts were created by Walt Disney and his animators. A number of Hollywood composers wrote the background music, including Alfred Newman and Russian-born composer Dimitri Tiomkin. After the first complete film was viewed by General Marshall along with U.S. Army staff, Marshall approached Capra: "Colonel Capra, how did you do it? That is a most wonderful thing."[43]

Officials made efforts to see that the films were seen in theaters throughout the U.S. They were translated into French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Chinese for use by other countries. Winston Churchill ordered that all of them be shown to the British public in theaters.[44] They are today often broadcast on television and used as a teaching aid.[30]

The Why We Fight series is widely considered a masterpiece of war information documentaries, and won an Academy Award. Prelude to War won the 1942 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. When his career ended, Capra regarded these films as his most important works. He was discharged from the service in 1945 as a colonel, having been awarded the Legion of Merit in 1943, the Distinguished Service Medal in 1945, the World War I Victory Medal (for his service in World War I), the American Defense Service Medal, the American Campaign Medal and the World War II Victory Medal.[2]

Post-war career (1946–1961)[]

It's a Wonderful Life (1946)[]

After the war ended, along with directors William Wyler and George Stevens, Capra founded Liberty Films. Their studio became the first independent company of directors since United Artists in 1919 whose goal was to make films without interference by studio bosses. However, the only pictures completed by the studio were It's a Wonderful Life (1946) and State of the Union (1948).[14] The first of these was a box office disappointment but was nominated for five Academy Awards.

While the film did not resonate with audiences in 1946, its popularity has grown through the years, partly due to frequent airings during those years it was in the public domain. In 1998, the American Film Institute (AFI) named it one of the best films ever made, putting it at 11th on AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies list of the top American films of all time. In 2006, the AFI put the film at the top of its AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers list, ranking what AFI considers the most inspirational American movies of all time. It would become Capra's last film to win major acclaim—his successful years were now behind him, although he directed five more films over the next 14 years.[14]

For State of the Union (1948), Capra changed studios. It would be the only time he ever worked for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Although the project had an excellent pedigree with stars Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn, the film was not a success, and Capra's statement, "I think State of the Union was my most perfect film in handling people and ideas" has few adherents today.[45]

Representing U.S. at International Film Festival[]

In January 1952, the U.S. Ambassador to India asked Capra to represent the U.S. film industry at an International Film Festival to be held in India. A State Department friend of Capra asked him and explained why his trip would be important:

[Ambassador] Bowles thinks the Festival is a Communist shenanigan of some kind, but he doesn't know what ... Bowles has asked for you. "I want a free-wheeling guy to take care of our interest on his own. I want Capra. His name is big here, and I've heard he's quick on his feet in an alley fight.[46]

After two weeks in India, Capra discovered that Bowles' fears were warranted, as many film sessions were used by Russian and Chinese representatives to give long political speeches. At a lunch with 15 Indian directors and producers, he stressed that "they must preserve freedom as artists, and that any government control would hinder that freedom. A totalitarian system—and they would become nothing but publicity men for the party in power." Capra had a difficult time communicating this, however, as he noted in his diary:

They all think some super-government or super-collection of individuals dictates all American pictures. Free enterprise is mystery to them. Somebody must control, either visible or invisible ... Even intellectuals have no great understanding of liberty and freedom ... Democracy is only a theory to them. They have no idea of service to others, of service to the poor. The poor are despised, in a sense.[47]

When he returned to Washington to give his report, Secretary of State Dean Acheson gave Capra his commendation for "virtually single-handedly forestalling a possible Communist take-over of Indian films". Ambassador Bowles also conveyed gratitude to Capra for "one helluva job".[48]

Disillusionment period and later years[]

Following It's a Wonderful Life and State of the Union, which were done soon after the war ended, Capra's themes were becoming out of step with changes in the film industry and the public mood. Friedman finds that while Capra's ideas were popular with depression-era and prewar audiences, they became less relevant to a prospering post-war America. Capra had become "disconnected from an American culture that had changed" during the previous decade.[30] Biographer Joseph McBride argues that Capra's disillusionment was more related to the negative effect that the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) had on the film industry in general. The HUAC interrogations in the early 1950s ended many Hollywood careers. Capra himself was not called to testify, although he was a prime target of the committee due to his past associations with many Hollywood blacklisted screenwriters.[30]

Capra blamed his early retirement from films on the rising power of stars, which forced him to continually compromise his artistic vision. He also claimed that increasing budgetary and scheduling demands had constrained his creative abilities.[30] Film historian Michael Medved agreed with Capra, noting that he walked away from the movie business because "he refused to adjust to the cynicism of the new order."[49] In his autobiography, written in 1971, Capra expressed his feelings about the shifting film industry:[50]

The winds of change blew through the dream factories of make-believe, tore at its crinoline tatters ... The hedonists, the homosexuals, the hemophiliac bleeding hearts, the God-haters, the quick-buck artists who substituted shock for talent, all cried: "Shake 'em! Rattle 'em! God is dead. Long live pleasure! Nudity? Yea! Wife-swapping? Yea! Liberate the world from prudery. Emancipate our films from morality!" ... Kill for thrill—shock! Shock! To hell with the good in man, Dredge up his evil—shock! Shock![49]

Capra added that in his opinion, "practically all the Hollywood film-making of today is stooping to cheap salacious pornography in a crazy bastardization of a great art to compete for the 'patronage' of deviates and masturbators."[51][Note 1]

Capra remained employable in Hollywood during and after the HUAC hearings but chose nonetheless to demonstrate his loyalty by attempting to re-enlist in the Army at the outbreak of the Korean War, in 1950. He was rejected due to his age.[52] He was later invited to join the Defense Department's newly formed Think Tank project, VISTA, but was denied the necessary clearance. According to Friedman, "these two rejections were devastating to the man who had made a career of demonstrating American ideals in film", along with his directing award-winning documentary films for the Army.

Later films (1950–1961)[]

Capra directed two films at Paramount Pictures starring Bing Crosby, Riding High (1950) and Here Comes the Groom (1951). By 1952, at the age of 55, Capra effectively retired from Hollywood filmmaking; he shifted to working with the California Institute of Technology, his alma mater, to produce educational films on science topics.[30]

From 1952 to 1956, Capra produced four science-related television specials in color for The Bell System Science Series: Our Mr. Sun (1956), Hemo the Magnificent (1957), The Strange Case of the Cosmic Rays (1957), and Meteora: The Unchained Goddess (1958). These educational science documentaries were popular favorites for school science classrooms for around 30 years.[53] It was eight years before he directed another theatrical film, A Hole in the Head (1959) with Frank Sinatra and Edward G. Robinson, his first feature film in color. His final theatrical film was with Glenn Ford and Bette Davis, named Pocketful of Miracles (1961), a remake of his 1933 film Lady for a Day. In the mid-1960s he worked on pre-production for an adaptation of Martin Caidin's novel Marooned, but budgetary constraints caused him to eventually shelve it.[54]

Capra's final film, Rendezvous in Space (1964), was an industrial film made for the Martin Marietta Company and shown at the 1964 New York World's Fair. It was exhibited at the New York Hall of Science after the Fair ended.

Directing style[]

Capra's directing style relied on improvisation to a great extent. He was noted for going on the set with no more than the master scenes written. He explained his reasoning:

What you need is what the scene is about, who does what to whom, and who cares about whom ... All I want is a master scene and I'll take care of the rest—how to shoot it, how to keep the machinery out of the way, and how to focus attention on the actors at all times.[55]

According to some experts, Capra used great, unobtrusive craftsmanship when directing, and felt it was bad directing to distract the audience with fancy technical gimmicks. Film historian and author William S. Pechter described Capra's style as one "of almost classical purity". He adds that his style relied on editing to help his films sustain a "sequence of rhythmic motion". Pechter describes its effect:

Capra's [editing] has the effect of imposing order on images constantly in motion, imposing order on chaos. The end of all this is indeed a kind of beauty, a beauty of controlled motion, more like dancing than painting ... His films move at a breathtaking clip: dynamic, driving, taut, at their extreme even hysterical; the unrelenting, frantic acceleration of pace seems to spring from the release of some tremendous accumulation of pressure.[55]

Film critic John Raeburn discusses an early Capra film, American Madness (1932), as an example of how he had mastered the movie medium and expressed a unique style:

The tempo of the film, for example, is perfectly synchronized with the action ... as the intensity of the panic increases, Capra reduces the duration of each shot and uses more and more crosscutting and jump shots to emphasize the "madness" of what is happening ... Capra added to the naturalistic quality of the dialogue by having speakers overlap one another, as they often do in ordinary life; this was an innovation that helped to move the talkies away from the example of the legitimate stage.[27]

As for Capra's subject matter, film author Richard Griffith tries to summarize Capra's common theme:

[A] messianic innocent ... pits himself against the forces of entrenched greed. His inexperience defeats him strategically, but his gallant integrity in the face of temptation calls for the goodwill of the "little people", and through their combined protest, he triumphs.[55]

Capra's personality when directing gave him a reputation for "fierce independence" when dealing with studio bosses. On the set he was said to be gentle and considerate, "a director who displays absolutely no exhibitionism."[56] As Capra's films often carry a message about basic goodness in human nature, and show the value of unselfishness and hard work, his wholesome, feel-good themes have led some cynics to term his style "Capra-corn". However, those who hold his vision in higher regard prefer the term "Capraesque".[30]

Capra's basic themes of championing the common man, as well as his use of spontaneous, fast-paced dialogue and goofy, memorable lead and supporting characters, made him one of the most popular and respected filmmakers of the 20th century. His influence can be traced in the works of many directors, including Robert Altman,[57] Ron Howard,[57] Masaki Kobayashi,[58] Akira Kurosawa,[59] John Lasseter,[60] David Lynch,[61] John Milius,[57] Martin Scorsese,[57] Steven Spielberg,[62] Oliver Stone[57] and François Truffaut.[63]

Personal life[]

Capra married actress Helen Howell in 1923. They divorced in 1928. He married Lucille Warner in 1932, with whom he had a daughter and three sons, one of whom, Johnny, died at age 3 following a tonsillectomy.[64]

Capra was four times president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and three times president of the Directors Guild of America, which he helped found. Under his presidency, he worked to give directors more artistic control of their films. During his career as a director, he retained an early ambition to teach science, and after his career declined in the 1950s, he made educational television films related to science subjects.[56]

Physically, Capra was short, stocky, and vigorous, and enjoyed outdoor activities such as hunting, fishing, and mountain climbing. In his later years, he spent time writing short stories and songs, along with playing guitar.[56] He collected fine and rare books during the 1930s and 1940s. Six hundred and forty items from his "distinguished library" were sold by Parke-Bernet Galleries at auction in New York in April 1949, realizing $68,000 ($739,600 today).[65]

His son Frank Capra Jr. was the president of EUE Screen Gems Studios in Wilmington, North Carolina, until his death on December 19, 2007. His grandsons, brothers Frank Capra III and Jonathan Capra, have both worked as assistant directors; Frank III worked on the 1995 film The American President, which referred to Frank Capra in the film's dialogue.[66]

Political views[]

Capra's political views coalesced in his movies, which promoted and celebrated the spirit of American individualism. A conservative Republican, Capra railed against Franklin D. Roosevelt during his tenure as governor of New York and opposed his presidency during the years of the Depression. Capra stood against government intervention during the national economic crisis.[1]

In his later years, Capra became a self-described pacifist and was very critical of the Vietnam War.[67][64]

Religious views[]

Capra wrote in his early adulthood that he was a "Christmas Catholic".

In his later years, Capra returned to the Catholic Church and described himself as "a Catholic in spirit; one who firmly believes that the anti-moral, the intellectual bigots, and the Mafias of ill will may destroy religion, but they will never conquer the cross".[68]

Death[]

In 1985, aged 88, Capra suffered one of a series of strokes.[69] He died in La Quinta, California, of a heart attack in his sleep in 1991 at the age of 94.[70] He was interred at Coachella Valley Public Cemetery in Coachella, California.[71]

He left part of his 1,100-acre (445 ha) ranch in Fallbrook, California, to the California Institute of Technology, to be used as a retreat center.[72] Capra's personal papers and some film-related materials are contained in the Wesleyan University Cinema Archives, which allows scholars and media experts full access.[73]

Legacy[]

During the golden age of Hollywood, Capra's "fantasies of goodwill" made him one of the two or three most famous and successful directors in the world.[56] Film historian Ian Freer notes that at the time of his death in 1991, his legacy remained intact:

He had created feelgood entertainments before the phrase was invented, and his influence on culture—from Steven Spielberg to David Lynch, and from television soap operas to greeting-card sentiments—is simply too huge to calculate.[5]

Director/actor John Cassavetes contemplating Capra's contribution to film quipped: "Maybe there really wasn't an America, it was only Frank Capra."[74] Capra's films were his love letters to an idealized America—a cinematic landscape of his own invention. The performances his actors gave were invariable portrayals of personalities developed into recognizable images of popular culture, "their acting has the bold simplicity of an icon ..."[75]

Like his contemporary, director John Ford, Capra defined and aggrandized the tropes of mythic America where individual courage invariably triumphs over collective evil. Film historian Richard Griffith speaks of Capra's "... reliance on sentimental conversation and the ultimate benevolence of ordinary America to resolve all deep conflicts."[76] "Average America" is visualized as "... a tree-lined street, undistinguished frame houses surrounded by modest areas of grass, a few automobiles. For certain purposes, it assumed that all real Americans live in towns like this, and so great is the power of myth, even the born city-dweller is likely to believe vaguely that he too lives on this shady street, or comes from it, or is going to."[77]

NYU professor Leonard Quart writes:

There would be no enduring conflicts—harmony, no matter how contrived and specious, would ultimately triumph in the last frame ... In true Hollywood fashion, no Capra film would ever suggest that social change was a complex, painful act. For Capra, there would be pain and loss, but no enduring sense of tragedy would be allowed to intrude on his fabulist world.[76]

Although Capra's stature as a director had declined in the 1950s, his films underwent a revival in the 1960s:

Ten years later, it was clear that this trend had reversed itself. Post-auteurist critics once more acclaimed Capra as a cinematic master, and perhaps more surprisingly, young people packed Capra festivals and revivals all over the United States.[56]

French film historian John Raeburn, editor of Cahiers du cinéma, noted that Capra's films were unknown in France, but there too his films underwent a fresh discovery by the public. He believes the reason for his renewed popularity had to do with his themes, which he made credible "an ideal conception of an American national character":

There is a strong libertarian streak in Capra's films, a distrust of power wherever it occurs and in whomever it is invested. Young people are won over by the fact that his heroes are uninterested in wealth and are characterized by vigorous ... individualism, a zest for experience, and a keen sense of political and social justice. ... Capra's heroes, in short, are ideal types, created in the image of a powerful national myth.[56]

In 1982, the American Film Institute honored Capra by giving him their AFI Life Achievement Award. The event was used to create the television film, The American Film Institute Salute to Frank Capra, hosted by James Stewart. In 1986, Capra received the National Medal of Arts. During his acceptance speech for the AFI award, Capra stressed his most important values:

The art of Frank Capra is very, very simple: It's the love of people. Add two simple ideals to this love of people: the freedom of each individual, and the equal importance of each individual, and you have the principle upon which I based all my films.

Capra expanded on his visions in his 1971 autobiography, The Name Above the Title:

Forgotten among the hue-and criers were the hard-working stiffs that came home too tired to shout or demonstrate in streets ... and prayed they'd have enough left over to keep their kids in college, despite their knowing that some were pot-smoking, parasitic parent-haters.

Who would make films about, and for, these uncomplaining, unsqueaky wheels that greased the squeaky? Not me. My "one man, one film" Hollywood had ceased to exist. Actors had sliced it up into capital gains. And yet—mankind needed dramatizations of the truth that man is essentially good, a living atom of divinity; that compassion for others, friend or foe, is the noblest of all virtues. Films must be made to say these things, to counteract the violence and the meanness, to buy time to demobilize the hatreds.[78]

Awards and honors[]

The Why We Fight series earned Capra the Legion of Merit in 1943 and the Distinguished Service Medal in 1945.[79][80]

In 1957, Capra was awarded the George Eastman Award, given by George Eastman House for distinguished contribution to the art of film.[81]

Los Angeles Mayor Sam Yorty, by a vote of the city council, declared May 12, 1962 as "Frank Capra Day". George Sidney, President of the Directors Guild stated that "This is the first time in the history of Hollywood, that the city of Los Angeles has officially recognized a creative talent." At the event ceremony, director John Ford announced that Capra had also received an honorary Order of the British Empire (OBE) on the recommendation of Winston Churchill.[82] Ford suggested publicly to Capra:

Make those human comedy-dramas, the kind only you can make—the kind of films America is proud to show here, behind the iron curtain, the bamboo curtain—and behind the lace curtain.[82]

In 1966, Capra was awarded the Distinguished Alumni Award from his alma mater Caltech.[83] (see section "Early Life", supra)

In 1972, Capra received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[84]

In 1974, Capra was awarded the Inkpot Award.[85]

In 1975, Capra was awarded the Golden Anchor Award by the U.S Naval Reserve's Combat Camera Group for his contribution to World War II Naval photography and production of the "Why We Fight" series. The award ceremony included a video salute by President Ford. Attending were many of Capra's favorite actors including Jimmy Stewart, Donna Reed, Pat O'Brien, Jean Arthur, and others.[86]

An annual It's a Wonderful Life celebration that Capra attended in 1981, during which he said, "This is one of the proudest moments of my life," was recounted in The New Yorker.[87]

He was nominated six times for Best Director and seven times for Outstanding Production/Best Picture. Out of six nominations for Best Director, Capra received the award three times. He briefly held the record for winning the most Best Director Oscars when he won for the third time in 1938, until this record was matched by John Ford in 1941, and then later surpassed by Ford in 1952. William Wyler also matched this record upon winning his third Oscar in 1959.[88]

The Academy Film Archive has preserved two of Capra's films, "The Matinee Idol" (1928) and "Two Down and One to Go!" (1945).[89]

Academy Awards and nominations[]

This section does not cite any sources. (September 2018) |

| Year | Film | Award | Winner |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1933 | Lady for a Day | Outstanding Production | Winfield Sheehan – Cavalcade |

| Best Director | Frank Lloyd –Cavalcade | ||

| 1934 | It Happened One Night | Outstanding Production | |

| Best Director | |||

| 1936 | Mr. Deeds Goes to Town | Outstanding Production | Hunt Stromberg – The Great Ziegfeld |

| Best Director | |||

| 1937 | Lost Horizon | Outstanding Production | Henry Blanke – The Life of Emile Zola |

| 1938 | You Can't Take It with You | Outstanding Production | |

| Best Director | |||

| 1939 | Mr. Smith Goes to Washington | Outstanding Production | David O. Selznick – Gone with the Wind |

| Best Director | Victor Fleming – Gone with the Wind | ||

| 1943 | Prelude to War | Best Documentary | |

| 1944 | The Battle of Russia | Best Documentary, Features | Desert Victory |

| 1946 | It's a Wonderful Life | Best Picture | Samuel Goldwyn – The Best Years of Our Lives |

| Best Director | William Wyler – The Best Years of Our Lives |

- American Film Institute

- Life Achievement Award (1982)

- Directors Guild of America

- Best Director Nomination for A Hole in the Head (1959)

- Life Achievement Award (1959)

- Best Director Nomination for Pocketful of Miracles (1961)

- Golden Globe Award

- Best Director Award for It's a Wonderful Life (1946)

- Venice Film Festival

- Mussolini Cups for best foreign film Nomination for It Happened One Night (1934)

- Mussolini Cups for best foreign film Nomination for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936)

- Golden Lion (1982)

- American Film Institute recognition

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)

- It's a Wonderful Life ... #20

- Mr. Smith Goes to Washington ... #26

- It Happened One Night ... #46

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers

- It's a Wonderful Life ... #1

- Mr. Smith Goes to Washington ... #5

- Meet John Doe ... #49

- Mr. Deeds Goes to Town ... #83

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs

- It Happened One Night ... #8

- Arsenic and Old Lace ... #30

- Mr. Deeds Goes to Town ... #70

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions

- It's a Wonderful Life ... #8

- It Happened One Night ... #38

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains

- 50 greatest movie heroes

- It's a Wonderful Life ... George Bailey ... #9

- Mr. Smith Goes to Washington ... Jefferson Smith ... #11

- 50 greatest movie villains

- It's a Wonderful Life ... Mr. Potter ... #6

- AFI's 10 Top 10

- Fantasy

- It's a Wonderful Life ... #3

- Romantic Comedies

- It Happened One Night ... #3

- Fantasy

- United States National Film Registry

- The Strong Man (1926)

- It Happened One Night (1934)

- Lost Horizon (1937)

- Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

- Why We Fight Series of seven films (1942)

- It's a Wonderful Life (1946)

Filmography[]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ Medved points out the irony in Capra's expression of disillusionment: Capra's film It Happened One Night (1934) was the first film to win all five top Oscars, and in 1991, a few months after Capra's death, The Silence of the Lambs also won all five top Oscars.[49]

References[]

- ^ a b Wilson 2013, p. 266.

- ^ a b Capra, Frank, COL - U.S. Army army.togetherweserved.com. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ a b The War Years; From Pearl Harbor to Dachau, many of Hollywood's top directors volunteered their creative talents to help win World War II. Their films from the front left a lasting document of the often brutal fight for freedom. Directors Guild of America. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Frank Capra - Colonel, U.S. Army Signal Corps, WWII Fort Gordon Historical Museum Society via Issuu. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Freer 2009, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Poague 2004, p. viii.

- ^ De Las Carreras, Maria Elena. "The Catholic Vision of Frank Capra." Crisis, 20, no. 2, February 2002. Retrieved: May 31, 2011.

- ^ a b McBride 1992, p. 16.

- ^ McBride 1992, p. 29.

- ^ McBride 1992, p. 30.

- ^ McBride 1992, p. 34.

- ^ [1] Archived July 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Caltech Alumni Association. Retrieved: December 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Wakeman 1987, p. 96.

- ^ a b c Stevens 2006, pp. 74–76.

- ^ a b c d e f Wakeman 1987, p. 97.

- ^ McBride, Joseph (2001). Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-839-1. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ Eggert, William D. "The Mystery of Harry Langdon profile, SilentsareGolden.com; accessed July 28, 2016.

- ^ McBride 1992, p. 200.

- ^ McBride 1992, p. 201.

- ^ McBride 1992, p. 189.

- ^ a b Barson 1995, pp. 56–63.

- ^ McBride 1992, p. 197.

- ^ McBride 1992, p. 199.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ^ McBride, Joseph (June 2, 2011). Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-60473-839-1.

- ^ McBride 1992, p. 203.

- ^ a b Wakeman 1987, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Wakeman 1987, p. 99.

- ^ Wakeman 1987, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pendergast 2000, pp. 428–29.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 259.

- ^ a b Beauchamp 2010, pp. 364–365.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 261.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 260.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 289.

- ^ Wakeman 1987, p. 101.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 314.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 322.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 326.

- ^ Kurash, John (February 25, 2009). "A Prelude to War". US Army. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ Rowen, Robert (June 14, 2002). "The New York Military Affairs Symposium". Bobrowen.com. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ Nathan Seeley, "Carlton Moss and African American Cultural Emancipation", Black Camera 9/2 (Spring 2018): 52-75. DOI: 10.2979/blackcamera.9.2.05 https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/blackcamera.9.2.05

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 341.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 336.

- ^ Poague 2004, p. 180.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 429.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 433.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 437.

- ^ a b c Medved 1992, p. 279.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 486.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 400.

- ^ "Legendary Hollywood Producer Had a Wonderful Life With Ceres Girl as Wife", The Ceres Courier, January 13, 2016.

- ^ Capra 1997, p. 443.

- ^ "'Marooned'", tcm.com; retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ^ a b c Wakeman 1987, p. 102.

- ^ a b c d e f Wakeman 1987, p. 103.

- ^ a b c d e "The Premiere Frank Capra Collection", DVD Talk Review of the DVD Video; retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ^ Christian, Diane and Bruce Jackson. "The Buffalo Film Seminars: Hara Kari (1962), directed by Masaki Kobayashi", csac.buffalo.edu, February 26, 2008; retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ^ "BAM/PFA Film Programs: Kurosawa." Archived August 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine banpfa.berkeley.edu. Retrieved: September 26, 2010.

- ^ Day, Aubrey "Film features: Interview: John Lasseter", totalfilm.com, June 3, 2009; retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ^ Barney 2009, pp. 35, 119, 265.

- ^ "Frank Capra: Hollywood Star Walk." The Los Angeles Times, September 3, 1991. Retrieved: September 26, 2010.

- ^ Dixon 1993, p. 150.

- ^ a b McBride, Joseph (June 2, 2011). Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-839-1.

- ^ 1947-, McBride, Joseph (2011). Frank Capra : the catastrophe of success. [Jackson]: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-839-1. OCLC 721907547.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- ^ McLellan, Dennis (December 21, 2007). "Son of film legend, producer, studio boss". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Capra, Frank (2004). Frank Capra: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-617-9.

- ^ "The Catholic Vision of Frank Capra". February 2002. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- ^ Lambert, Gavin. "Book review: "The World Outside the Pictures: 'Frank CAapra: The Catastrophe of Success'." The Los Angeles Times, May 27, 1992.

- ^ Frank Capra profile, FilmReference.com; retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ Brooks 2006, p. 248.

- ^ "75th Year Booklet: The Caltech Y History." caltechy.org. Retrieved: July 24, 2011.

- ^ "Description of the Capra Collection" Archived May 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, wesleyan.edu; retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ Lazere 1987, p. 178.

- ^ Dickstein 2010, pp. 479–80.

- ^ a b Dickstein 2010, p. 479.

- ^ Dickstein 2010, p. 480.

- ^ Capra 1971, p. 468.

- ^ Limited, Alamy. "Stock Photo Lt. Col. Frank Capra, receives the Legion of Merit. The Hollywood movie director was chief of the U.S. Army Signal Corps motion". Alamy.

- ^ "Marshall, Frank Capra & Film – George C. Marshall Foundation". November 28, 2014.

- ^ "Awards granted by George Eastman House International Museum of Photography & Film" Archived April 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, eastmanhouse.org; retrieved April 30, 2012.

- ^ a b Capra 1971, p. 488.

- ^ "Caltech : Distinguished Alumni Awards" (PDF). Static1.squarespace.com. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ Inkpot Award

- ^ https://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/document/0122/1252586.pdf

- ^ "Talk of the Town." The New Yorker, January 12, 1981, pp. 29–31.

- ^ "Frank Capra". IMDb. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- ^ "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive.

Bibliography[]

- Barney, Richard A. David Lynch: Interviews (Conversations with Filmmakers Series). Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2009. ISBN 978-1-60473-237-5

- Barson, Michael. The Illustrated Who's Who of Hollywood Directors: The Sound Era. New York: Noonday Press, 1995. ISBN 0-374-52428-9

- Beauchamp, Cari. Joseph P. Kennedy Presents: His Hollywood Years. New York: Vintage, 2010. ISBN 978-0-307-47522-0

- Brooks, Patricia and Johnathan. "Chapter 8: East L.A. and the Desert." Laid to Rest in California: A Guide to the Cemeteries and Grave Sites of the Rich and Famous. Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-7627-4101-4

- Capra, Frank. Frank Capra, The Name Above the Title: An Autobiography. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1971. ISBN 0-306-80771-8.

- Digitized on the HathiTrust Digital Library, Limited view (search only) OCLC 679451848.

- Chandler, Charlotte. The Girl Who Walked Home Alone: Bette Davis, A Personal Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 0-7862-8639-3

- Dickstein, Morris. Dancing in The Dark: A Cultural History of The Great Depression. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010. ISBN 978-0-393-07225-9

- Dixon, Wheeler W. The Early Film Criticism of Francois Truffaut. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-253-20771-5

- Freer, Ian. Movie Makers: 50 Iconic Directors from Chaplin to the Coen Brothers. London: Quercus Publishing Plc, 2009. ISBN 978-1-84724-512-0

- Kotsabilas-Davis, James and Myrna Loy. Being and Becoming. New York: Primus, Donald I Fine Inc., 1987. ISBN 1-55611-101-0

- Lazere, Donald. American Media and Mass Culture: Left Perspectives. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0-520-04496-8

- Medved, Michael. Hollywood vs. America: Popular Culture and the War on Traditional Values. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. ISBN 978-0-06-016882-7

- McBride, Joseph. Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success. New York: Touchstone Books, 1992. ISBN 0-671-79788-3

- Oderman, Stuart. Talking To the Piano Player: Silent Film Stars, Writers and Directors Remember. Albany, Georgia: BearManor Media, 2005. ISBN 1-59393-013-5

- Poague, Leland. Frank Capra: Interviews (Conversations With Filmmakers Series). Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2004. ISBN 978-1-57806-617-9

- Pendergast, Tom and Sara, eds. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, Vol. 1. Detroit: St. James Press, 2000. ISBN 1-55862-348-5

- Stevens, George Jr. Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood's Golden Age. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4000-4054-4

- Sullivan, Daniel J. (2005). "Sentimental Hogwash? On Capra's It's a Wonderful Life" (PDF). Humanitas. XVIII (1 and 2): 115–40. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- Wakeman, John, ed. World Film Directors: Volume One, 1890–1945. New York: H.W. Wilson Co., 1987. ISBN 978-0-8242-0757-1

- Wiley, Mason and Damien Bona. Inside Oscar: The Unofficial History of the Academy Awards. New York: Ballantine Books, 1987. ISBN 0-345-34453-7

- Wilson, Victoria. A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True 1907–1940. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013, ISBN 978-0-6848-3168-8

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Frank Capra |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frank Capra. |

- Capra Smith and Doe: Filming the American Hero from American Studies at the University of Virginia

- Frank Capra at IMDb

- Frank Capra at the TCM Movie Database

- Bibliography

- Capra before he became "Capraesque" BFI Sight & Sound magazine November 2010 article on Capra's early career, by Joseph McBride

- Frank Capra accepts Life Achievement Award on YouTube

- James Stewart at the "Tribute to Frank Capra" on YouTube

- Bette Davis at the "Tribute to Frank Capra" on YouTube

- Jack Lemmon at the "Tribute to Frank Capra" on YouTube

- Frank Capra receiving Academy Awards on YouTube

- Discussing Lost Horizon on Dick Cavett Show on YouTube

- Frank Capra at the 1971 San Francisco International Festival

- 1897 births

- 1991 deaths

- American anti-communists

- American electrical engineers

- American pacifists

- United States Army personnel of World War I

- United States Army personnel of World War II

- Best Directing Academy Award winners

- Best Director Golden Globe winners

- Presidents of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- Presidents of the Directors Guild of America

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- California Institute of Technology alumni

- American film directors of Italian descent

- Propaganda film directors

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army)

- Italian emigrants to the United States

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- Burials at Coachella Valley Public Cemetery

- American male screenwriters

- Inkpot Award winners

- Film producers from California

- Italian film producers

- United States Army Air Forces officers

- First Motion Picture Unit personnel

- United States Army colonels

- Honorary Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- People from La Quinta, California

- AFI Life Achievement Award recipients

- Film directors from California

- Catholics from California

- Screenwriters from California

- Engineers from California

- 20th-century American engineers

- California Republicans

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American screenwriters

- Old Right (United States)

- United States Army Air Forces personnel of World War II