Frank Russell, 2nd Earl Russell

The Earl Russell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for India | |

| In office 1 December 1929 – 3 March 1931 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | Drummond Shiels |

| Succeeded by | The Lord Snell |

| Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Transport | |

| In office 11 June 1929 – 1 December 1929 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | John Moore-Brabazon |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Ponsonby |

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Temporal | |

| In office 13 August 1886 – 3 March 1931 Hereditary Peerage | |

| Preceded by | The 1st Earl Russell |

| Succeeded by | The 3rd Earl Russell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 August 1865 |

| Died | 3 March 1931 (aged 65) |

| Spouse(s) | Mabel Edith Scott (divorced) Marion Somerville (nee Cooke) (divorced) Elizabeth von Arnim (separated) |

| Parents | Viscount and Viscountess Amberley |

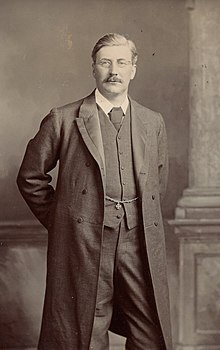

John Francis Stanley Russell, 2nd Earl Russell, known as Frank Russell (12 August 1865 – 3 March 1931), was the elder surviving son of Viscount and Viscountess Amberley, and was raised by his paternal grandparents after his unconventional parents both died young. He was the grandson of the former prime minister John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, and elder brother of the philosopher Bertrand Russell. He was married three times, lastly to Elizabeth von Arnim, who caricatured him in her novel Vera.[1] Despite his landmark achievements in other respects, this Earl Russell is most famous for being tried for bigamy in the House of Lords in 1901, and was known to Edwardian society as the "Wicked Earl".

Education[]

Russell proved hard work for his grandparents and was sent to school; first Cheam (1877) and then Winchester College (January 1879). Winchester became his spiritual home, and the friends he made there his surrogate family. It was there that he befriended poet and critic Lionel Johnson, whom he would describe as “the greatest influence of my life at Winchester”[2] though Johnson was the younger man. When Russell went up to Balliol College, Oxford, in 1883, the pair wrote long, earnest letters to each other in which they explored spiritual matters and questions of sin and morality. Twice the correspondence was banned by Johnson's father who feared that Russell's Buddhist beliefs would have a baneful influence on Johnson's welfare as a Christian. Not to be thwarted, Russell engaged an Oxford friend, Charles Edward Sayle, to correspond with Johnson on his behalf. Johnson also corresponded with Sayle's Rugby friend Jack Badley. In 1919, Russell anonymously published Johnson's side of the correspondence with all three as Some Winchester Letters of Lionel Johnson.[3]

Oxford[]

At Balliol, Russell read Classics. The famous Greek scholar Benjamin Jowett was then Master of Balliol and also Vice-Chancellor of the University. Russell found Oxford stimulating, welcoming the “untrammelled and unfettered discussions on everything in heaven and earth”,[4] but his Oxford career was cut dramatically short when in May 1885, he was sent down by Jowett for supposedly writing a "scandalous" letter to another male undergraduate. Russell denied the charges but was refused a formal inquiry. Incensed at having been falsely accused, he lost his temper with Jowett, telling him he was no gentleman, and left the college. In an unprecedented move, Jowett blocked Russell's return to Balliol and denied him the necessary bene discessit to enable him to transfer to Cambridge with his approbation. After leaving Oxford, Russell toured the USA where he met philosopher George Santayana. The pair became lifelong friends and later Santayana would claim that Russell told him in confidence the real reason for his sending down: that Lionel Johnson had stayed overnight in his rooms and when spotted by the authorities had been declared too young to be Russell's "natural friend". There is evidence to suggest that even this is not the real version of events. Nevertheless, the scandal, which remains steeped in mystery, would be revisited on Russell throughout his life, casting doubt on his sexuality, and, according to Santayana, earning him the epithet "Wicked Earl".[5]

Marital history[]

Frank Russell was twice divorced, and separated permanently from his third and last wife three years after they married. He also had extramarital affairs.

His first wife was Mabel Edith Scott, daughter of "adventuress" Lady Selina (Lina) Scott and her husband Sir Claude Edward Scott (1840-1880) of the Scott baronets of Lytchet Minster. They married in 1890; the marriage was a disaster, lasting only three months. Mabel sued to judicially separate from him (and lost) in 1891, accusing him in the process of "immoral behaviour" with another university friend, Herbert Ainslie Roberts. Having failed to convince the jury, she subsequently attempted to obtain a separation by indirect means, suing for restitution of conjugal rights in 1894.[6] The Earl counter-sued on the ground that her continued accusations of sodomy amounted to legal cruelty, and was granted a judicial separation in 1895. Mabel appealed and the verdict was overturned. The case went all the way to the House of Lords where the appellate judges denied them both satisfaction, binding the definition of legal cruelty to physical violence and making Russell v. Russell [2] a case of legal significance for the next 70 years. Russell's mother-in-law also tried to harass him, by distributing 500 statements to members of the Commons and Lords, to relatives, the press and other key figures in society, accusing Russell of sodomy. He sued for criminal libel and Lina was convicted at the Old Bailey in 1897 and sentenced to 8 months' imprisonment.[7] According to Russell, the whole 10-year divorce process cost him a staggering £30,000. Neither fared well: Mabel, Countess Russell, was forced to make her living thereafter by singing on the variety stage.

Russell next married Marion (Cooke) (Watson) Somerville (born c. 1857–1858), known as Mollie.[8] She was the twice-divorced daughter of an Irish master-shoemaker. Mollie was a feminist, suffragist and radical Liberal. They married in the United States in 1900, after establishing domicile in that country and obtaining a divorce in Nevada - the first celebrity Reno Divorce on record. The British authorities considered such a divorce invalid,[9] and Lord Russell was arrested and was convicted of bigamy in the House of Lords on 18 July 1901. He was sentenced to only three months in prison on account of the "extreme torture" he had suffered in his first marriage.[10] Mabel, the first Countess Russell, obtained a divorce on the strength of his conviction, and Russell married Mollie on 31 October 1901, three days after the divorce became absolute. Mollie divorced Russell in 1915, possibly with his collusion.[8]

Russell married, thirdly, the novelist Elizabeth von Arnim (née Mary Annette Beauchamp), widow of Count Henning August von Arnim-Schlagenthin (d. 1910). Von Arnim had a three-year affair with H.G. Wells, and ended her relationship with Wells when his other lover Rebecca West became pregnant. She became involved with Russell in 1914 and married him on 11 February 1916.[11][12] The marriage failed quickly and acrimoniously, and the couple separated in 1919. However, they never divorced. Von Arnim famously caricatured Russell in her 1921 novel Vera and in response he blanked her in his memoirs written in 1923. At the start of the Second World War, von Arnim moved to the United States, where she died in 1941.[13]

Earl Russell had no children, but his second and third marriages brought him several stepchildren. His second wife, Mollie, had one son by her first husband and two sons by her second husband. His third wife, Elizabeth, had five children by her first husband.

Russell as a motoring enthusiast[]

Russell was an early motorist and an active member of the RAC and Motor Union. He was an outspoken defender of motorists' rights. He is famed for having the registration A 1. This is frequently reported as being the first number plate issued in Britain, but was most likely not – it was, however, the first registration issued by the London County Council (LCC). "Motoring Illustrated" of 19 December 1903 reported that the London County Council started issuing numbers on 7 December 1903, whereas other authorities started before that date. From surviving records, the first number known to have been issued is Hastings' DY 1 issued on 23 November 1903.[14] It is also frequently reported that the Earl queued all night to obtain the number and only just beat another potential applicant for the number by a few seconds. There does not appear to be any contemporary record of this in motoring journals, though several report that he obtained the number A 1. Thus, it seems unlikely that this story is correct too.

Political and legal career[]

After the passing of the 1894 Local Government Act, Russell was elected to Cookham Parish and District Councils and became a Guardian of the Poor responsible for the administration of Maidenhead workhouse. In the same year he also became JP for Berkshire. In 1895 he was elected onto London County Council as Progressive Party candidate for West Newington. After failing to take the Hammersmith seat in 1898, he was made an Alderman. He became a member of the National Liberal Club (NLC) and the Reform Club.

After his release from prison, he sought to reform the divorce laws that had put him there, introducing four bills into the House of Lords over a six-year period (all of which were considered too radical) and established the Society for Promoting Reforms in the Marriage and Divorce Laws of England which was later absorbed into the Divorce Law Reform Union. He published a treatise on the inequality of the divorce laws in 1912. Russell's attempts to reform divorce laws were partly negated by his own personal history, but he is still rightly considered a pioneer in the field.

Underpinning Russell's campaign for divorce reform was a protest against the irrational influence of the Church in public policy. His argument was that the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act which legislated divorce in England and Wales, worded in such a way as to be “as nearly as may be conformable to the principles and rules on which the Ecclesiastical Courts have heretofore acted",[15] "would never have been a sane politician or jurist into a code of divorce written on a blank page".[16] In 1902, Russell had publicly declared himself an agnostic in the preface to Lay Sermons. He spent the rest of his career fighting what he called "the sinister shadow of the Church".[17]

With second wife, Mollie, he became an active campaigner for women's suffrage in 1908, and in the 1920s was a keen supporter of Marie Stopes's campaign for constructive birth control.

He was called to the Bar at Gray's Inn[18] in 1905 and spent most of his career defending motorists and suffragists.

Russell became a Fabian in 1912 and was the first peer to declare his support for the Labour Party. He was made Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of Transport and then Under-Secretary of State for India in Ramsay MacDonald's government from 1929 to 1931; a career cut short by a sudden fatal heart attack.

Publications[]

- Lay Sermons (1902)

- Divorce (1912)

- Some Winchester Letters of Lionel Johnson (1919)

- My Life and Adventures (1923)

Other activities[]

Russell was chairman of a number of companies, including Plenty & Son of Newbury, Humber, and the Globe & Phoenix Mining Co.

Russell supported his brother's pacifism during the First World War, and was a close friend of George Santayana and Lionel Johnson.

References[]

- ^ Erica Brown. Literary Encyclopedia: Elizabeth von Arnim (1866–1941).

- ^ Russell, Earl (1923). My Life and Adventures. London: Cassell & Co. pp. 89.

- ^ Russell, Earl (1919). Some Winchester Letters of Lionel Johnson. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- ^ My Life and Adventures. p. 104.

- ^ Derham, Ruth (Winter 2017–18). "'A Very Improper Friend': the influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell". Russell: The Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies. 37:2: 267–362.

- ^ Under the , failure to comply with an order of restitution of conjugal rights served to establish desertion ("statutory desertion") which gave the other spouse the right to an immediate decree of judicial separation, and, if coupled with the husband’s adultery, allowed the wife to obtain an immediate divorce. See [1]

- ^ "LADY SCOTT TO BE RELEASED.; Her Eight Months in Holloway for Libeling Earl Russell Expired." The New York Times 15 July 1897. This Lady Selina Scott was not Lady Selina Bond, née Scott (d. 1891) Archived 31 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, sister of the 3rd Earl of Eldon and wife of Nathaniel Bond.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ian Watson. "Mollie, Countess Russell", Russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies 23 (2003): 65–68.

- ^ "EARL RUSSELL ARRESTED His Nevada Marriage Results in a Charge of Bigamy." The New York Times, 18 June 1901.

- ^ "EARL RUSSELL CONVICTED; Pleads Guilty to Charge of Bigamy Before ..." The New York Times, 19 July 1901.

- ^ C.D. Merriman. "Elizabeth von Arnim: Biography and Works"

- ^ Erica Brown. Literary Encyclopedia: Elizabeth von Arnim (1866–1941). Brown says that Elizabeth would have been happy to have continued the affair, but Frank Russell wanted to divorce his second wife and marry her.

- ^ The Enchanted April NYRB Classics

- ^ Newall, Les (September 1995). "A 1 – Britain's First Registration". "1903 and All That" Newsletter (61): 8.

- ^ 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act

- ^ Russell (1912). Earl. London: William Heinemann. pp. v.

- ^ Russell, Earl (1922). "The Difficulties of Bishops". Rational Press Association Annual: 25–31.

- ^ "Russell, Earl". Cracroft's Peerage. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

Biographies[]

- Derham, Ruth. Bertrand's Brother: The Marriages, Morals and Misdemeanours of Frank, 2nd Earl Russell. Amberley, Stroud, April 2021.

Further reading[]

- Anonymous. Russell's parents and grandparents. This university website has portraits of the 2nd Earl Russell and describes him as "already quite uncontrollable, as later demonstrated by his marital and financial turbulence" when he came to live with his grandparents.

- Derham, Ruth. "Frank Russell's Diverse Writing and Speaking Career: A Bibliographical Guide", Russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies, 41 (2021): 62-76.

- Derham, Ruth. "Bible Studies: Frank Russell and the Book of Books", Russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies 40 (2020): 43–51.

- Derham, Ruth. "'A Very Improper Friend': the influence of Jowett and Oxford on Frank Russell", Russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies 37 (2017–18): 267–362.

- Derham, Ruth. "Ideal Sympathy: The Unlikely Friendship of George Santayana and Frank, 2nd Earl Russell", Overheard in Seville 36 (2018): 12–25.

- Furneaux, Rupert. Tried by their Peers. Cassell, London, 1959. Two chapters are devoted to trials for bigamy, that of Elizabeth Chudleigh, Duchess of Kingston, and that of the 2nd Earl Russell.

- Watson, Ian. "Mollie, Countess Russell", Russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies 23 (2003): 65–68.

- Labour Party (UK) councillors

- Earls Russell

- British people convicted of bigamy

- 1865 births

- 1931 deaths

- Russell family

- Members of London County Council

- British politicians convicted of crimes

- Progressive Party (London) politicians

- Labour Party (UK) hereditary peers