Frick Collection

| |

| |

| Established | 1935 |

|---|---|

| Location | 1 East 70th Street Manhattan, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°46′16″N 73°58′02″W / 40.7712°N 73.9673°WCoordinates: 40°46′16″N 73°58′02″W / 40.7712°N 73.9673°W |

| Type | Art[1] |

| Director | Ian Wardropper |

| Public transit access | Subway: Bus: M1, M2, M3, M4, M66, M72, M98, M101, M102, M103 |

| Website | www |

The Frick Collection is an art museum in New York City. Its permanent collection features Old Master paintings and European fine and decorative arts, including works by Bellini, Fragonard, Goya, Rembrandt, Turner, Velázquez, Vermeer, and many others. The museum was founded by the industrialist Henry Clay Frick (1849–1919), and its collection has more than doubled in size since opening to the public in 1935. The Frick also houses the Frick Art Reference Library, a premier art history research center established in 1920 by Helen Clay Frick (1888–1984).

History[]

The Frick Collection became a public institution when Henry Clay Frick bequeathed his art collection, as well as his Upper East Side residence at 1 East 70th Street, to the public for the enjoyment of future generations.

Frick started his substantial collection as soon as he began amassing his fortune. A considerable portion of his art collection is located in his former residence “Clayton” in Pittsburgh, which is today a part of the Frick Art & Historical Center. Another part was given by his daughter and heiress Helen to the Frick Fine Arts Building, which is on the campus of the University of Pittsburgh.

The family did not permanently move from Pittsburgh to New York until 1905. Henry Frick initially leased the Vanderbilt house at 640 Fifth Avenue, to which he moved a substantial portion of his collection. He had his permanent residence built between 1912 and 1914 by Thomas Hastings of Carrère and Hastings. He stayed in the house until his death in 1919. He willed the house and all of its contents, including the works of art, furniture, and decorative objects, as a public museum. His widow Adelaide Howard Childs Frick, however, retained the right of residence and continued living in the mansion with her daughter Helen. After Adelaide Frick died in 1931, the conversion of the house into a public museum started.

John Russell Pope altered and enlarged the building in the early 1930s to adapt it to use as a public institution. It opened to the public on December 16, 1935. Various additions to the architecture and landscape architecture of the museum site have been considered over the years including the placement of a prominent magnolia garden from the 1930s. As stated by the museum announcements: "As a result of a decision of the Board of Trustees in 1939, three magnolias were selected for the Fifth Avenue garden. The two trees on the lower tier are Saucer Magnolias (Magnolia soulangeana) and the species on the upper tier by the flagpole is a Star Magnolia (Magnolia stellata)."[2]

Further expansions of the museum took place in 1977 and in 2011. In 2014, the museum announced further expansion plans, but came up against community opposition because it would result in the loss of a garden. The Frick ultimately dropped those plans and is said to be considering other options.[3][4][5]

In March 2021, the Collection temporarily relocated to Frick Madison, at the Marcel Breuer-designed building at 945 Madison Avenue, during the renovation of its historic building.[6]

Collection[]

The Frick is one of the preeminent small art museums in the United States, with a high-quality collection of old master paintings and fine furniture housed in nineteen galleries of varying size within the former residence. Frick had intended the mansion to become a museum eventually, and a few of the paintings are still arranged according to Frick's design. Besides its permanent collection, the Frick has always organized small, focused temporary exhibitions.[7]

The collection features some of the best-known paintings by major European artists as well as numerous works of sculpture and porcelain. It also has 18th-century French furniture, Limoges enamel, and Oriental rugs.[1] After Frick's death, his daughter, Helen Clay Frick, and the Board of Trustees expanded the collection: nearly half of the collection's artworks have been acquired since 1919. Although the museum cannot lend the works of art that belonged to Frick, as stipulated in his will, The Frick Collection does lend artworks and objects acquired since his death.[7]

Included in the collection are Jean-Honoré Fragonard's masterpiece The Progress of Love, three paintings by Johannes Vermeer including Mistress and Maid, two paintings by Jacob van Ruisdael including Quay at Amsterdam,[8] and Piero della Francesca's St. John the Evangelist.

Temporary exhibits[]

When the Mauritshuis in The Hague was under reconstruction in 2013 some of its works, including Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring and Carel Fabritius's The Goldfinch, toured the United States and, in New York, were exhibited at the Frick.[9]

Frick Art Reference Library[]

The Frick Collection oversees the nearby Frick Art Reference Library. The collections held at the library focus on art of the Western tradition from the fourth century to the mid-twentieth century, and chiefly include information about paintings, drawings, sculpture, prints, and illuminated manuscripts. Archival materials augment its research collections. Prior to opening in 1924, Helen Clay Frick used the basement bowling alley as storage space for the library.[10] The library quickly became known as a prime resource for students.[11]

Management[]

Attendance[]

According to The Art Newspaper, the Frick Collection has a typical annual attendance of 275,000 to 300,000.[12][7]

Governance[]

In 2011, Ian Wardropper succeeded Anne Poulet, who had run the Frick Collection as director since 2003.[13] Poulet took the position after Samuel Sachs II stepped down after running the institution for six years. Poulet was the first female director of the Frick.[14] During her time at the Frick Collection, Poulet increased the museum’s small board of trustees, adding 10 new members. She also introduced the Director’s Circle, a group of 44 members who each give a minimum of $25,000 a year to the Frick Collection, although many have made significantly larger contributions.[14]

Funding[]

By 1997, the Frick Collection had an operating budget of $10 million and an endowment of $170 million.[15] Despite its large endowment, the institution still needs money to preserve the building.[7]

Education[]

In 2008, the Frick hired Rika Burnham as head of their education department. Burnham introduced several changes to the museum, including the introduction of monthly free entrance to the museum, called First Fridays.[16] First Fridays include gallery talks and activities for visitors.

Artworks[]

Featured artists include:

|

|

Selected highlights[]

Giovanni Bellini, St. Francis in Ecstasy, 1478

Titian, Portrait of a Man in a Red Cap, c. 1516

Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Thomas More, 1527

Hans Holbein the Younger, Thomas Cromwell, 1532 or 1533

Agnolo di Cosimo (Bronzino), Portrait of Ludovico Cappon, 1551

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Three Soldiers, 1568

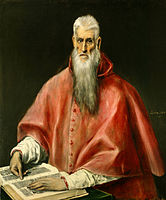

El Greco, Saint Jerome, c. 1590–1600

Rembrandt, The Polish Rider, 1655

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait, 1658

Jan Vermeer, Officer and Laughing Girl, 1657

Jan Vermeer, Girl Interrupted at Her Music, 1658–1661

Jan Vermeer, Mistress and Maid, 1667

François Boucher, The Four Seasons (Spring), 1755

François Boucher, The Four Seasons (Summer), 1755

François Boucher, The Four Seasons (Autumn), 1755

François Boucher, The Four Seasons (Winter), 1755

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Secret Meeting, 1771

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Progress of Love - Love Letters, 1771-1772

Francisco Goya, The Forge, 1817

John Constable, The White Horse, 1819

J.M.W. Turner, The Harbour of Dieppe, 1826

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Louise de Broglie, Countess d'Haussonville, 1845

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Mother and Children (La Promenade), 1875–76

James McNeill Whistler, Harmony in Pink and Grey (Portrait of Lady Meux), 1881

J.M.W. Turner, Cologne, the Arrival of a Packet Boat in the Evening, 1826

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Perseus and Andromeda, 1730–31

J.M.W. Turner, Mortlake Terrace Early Summer Morning, 1826

Hendrick van der Burgh, Drinkers before the Fireplace, 1660

Gentile Bellini, Doge Giovanni Mocenigo, 1478-1485

See also[]

References[]

Notes

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Frick Collection: About". ARTINFO. 2008. Archived from the original on October 5, 2008. Retrieved July 28, 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Frick online library. Description of architecture and landscape architecture. [1].

- ^ Pogebrin, Robin (June 9, 2014) "Frick Seeks to Expand Beyond Jewel-Box Spaces" The New York Times

- ^ Pogebrin, Robin (November 9, 2014) "Frick’s Plan for Expansion Faces Fight Over Loss of Garden" The New York Times

- ^ Pogebrin, Robin (June 3, 2015) "Frick Museum Abandons Contested Renovation Plan" The New York Times

- ^ Farago, Jason (February 25, 2021). "The Frick Savors the Opulence of Emptiness". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Carol Vogel (September 7, 1998), Director Tries Gentle Changes For the Frick New York Times.

- ^ "Jacob van Ruisdael". Frick Collection. Archived from the original on October 7, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2016.

- ^ Past Exhibition: Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Hals

- ^ Feuer, Alan (June 10, 2009). "In Frick's Basement, a Secret Masterpiece". The New York Times. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- ^ John Russell (November 10, 1984), Helen Clay Frick Dies At 96 New York Times.

- ^ Julia Halperin (January 11, 2014), Frick’s finch lays golden egg The Art Newspaper.

- ^ Kate Taylor and Carol Vogel (May 19, 2011), The Frick Collection Names a New Director New York Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Carol Vogel (September 22, 2010), Director of Frick Collection Will Retire in Fall of 2011 New York Times.

- ^ Carol Vogel (May 13, 1997), Frick Finds Its Director In Detroit New York Times.

- ^ "The Frick Launches Free Monthly Evening Series- First Fridays | The Frick Collection". www.frick.org. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

Further reading

- Bailey, Colin B. (2006). Building the Frick Collection: An Introduction to the House and its Collections. New York: Frick Collection, in association with Scala Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 1-85759-381-2. (Press Release, October 11, 2006, Retrieved November 8, 2013)

- Bernice Davidson, Susan Galassi. Art in the Frick Collection : Paintings, Sculpture, Decorative Arts. Harry N Abrams. 1996. ISBN 978-0810919723

- Scala Publishers. Frick Collection: Handbook of Paintings. Scala Arts & Heritage. 2006. ISBN 978-1857593280

- Bernice Davidson, Edgar Munhall, Nadia Tscherny. Paintings from the Frick Collection . Harry N. Abrams. 1991. ISBN 978-0810937109

- Colin B. Bailey. Fragonard's Progress of Love at The Frick Collection. GILES. 2011. ISBN 978-1904832607

- Joseph Focarino. The Frick Collection, An Illustrated Catalogue. Volume IX: Drawings, Prints, and Later Acquisitions. Frick Collection. 2003 ISBN 978-0691038360

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frick Collection. |

- Frick Collection

- 1935 establishments in New York (state)

- Art museums established in 1935

- Art museums in New York City

- Fifth Avenue

- Former private collections in the United States

- Frick Art Reference Library

- Historic house museums in New York City

- Museums in Manhattan

- Upper East Side