Fundamental theorem of arithmetic

In number theory, the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, also called the unique factorization theorem, states that every integer greater than 1 can be represented uniquely as a product of prime numbers, up to the order of the factors.[3][4][5] For example,

The theorem says two things about this example: first, that 1200 can be represented as a product of primes, and second, that no matter how this is done, there will always be exactly four 2s, one 3, two 5s, and no other primes in the product.

The requirement that the factors be prime is necessary: factorizations containing composite numbers may not be unique (for example, ).

This theorem is one of the main reasons why 1 is not considered a prime number: if 1 were prime, then factorization into primes would not be unique; for example,

Euclid's original version[]

Book VII, propositions 30, 31 and 32, and Book IX, proposition 14 of Euclid's Elements are essentially the statement and proof of the fundamental theorem.

If two numbers by multiplying one another make some number, and any prime number measure the product, it will also measure one of the original numbers.

— Euclid, Elements Book VII, Proposition 30

(In modern terminology: if a prime p divides the product ab, then p divides either a or b or both.) Proposition 30 is referred to as Euclid's lemma, and it is the key in the proof of the fundamental theorem of arithmetic.

Any composite number is measured by some prime number.

— Euclid, Elements Book VII, Proposition 31

(In modern terminology: every integer greater than one is divided evenly by some prime number.) Proposition 31 is proved directly by infinite descent.

Any number either is prime or is measured by some prime number.

— Euclid, Elements Book VII, Proposition 32

Proposition 32 is derived from proposition 31, and proves that the decomposition is possible.

If a number be the least that is measured by prime numbers, it will not be measured by any other prime number except those originally measuring it.

— Euclid, Elements Book IX, Proposition 14

(In modern terminology: a least common multiple of several prime numbers is not a multiple of any other prime number.) Book IX, proposition 14 is derived from Book VII, proposition 30, and proves partially that the decomposition is unique – a point critically noted by André Weil.[6] Indeed, in this proposition the exponents are all equal to one, so nothing is said for the general case.

Article 16 of Gauss' Disquisitiones Arithmeticae is an early modern statement and proof employing modular arithmetic.[1]

Applications[]

Canonical representation of a positive integer[]

Every positive integer n > 1 can be represented in exactly one way as a product of prime powers:

where p1 < p2 < ... < pk are primes and the ni are positive integers. This representation is commonly extended to all positive integers, including 1, by the convention that the empty product is equal to 1 (the empty product corresponds to k = 0).

This representation is called the canonical representation[7] of n, or the standard form[8][9] of n. For example,

- 999 = 33×37,

- 1000 = 23×53,

- 1001 = 7×11×13.

Factors p0 = 1 may be inserted without changing the value of n (for example, 1000 = 23×30×53). In fact, any positive integer can be uniquely represented as an infinite product taken over all the positive prime numbers:

where a finite number of the ni are positive integers, and the rest are zero. Allowing negative exponents provides a canonical form for positive rational numbers.

Arithmetic operations[]

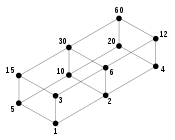

The canonical representations of the product, greatest common divisor (GCD), and least common multiple (LCM) of two numbers a and b can be expressed simply in terms of the canonical representations of a and b themselves:

However, integer factorization, especially of large numbers, is much more difficult than computing products, GCDs, or LCMs. So these formulas have limited use in practice.

Arithmetic functions[]

Many arithmetic functions are defined using the canonical representation. In particular, the values of additive and multiplicative functions are determined by their values on the powers of prime numbers.

Proof[]

The proof uses Euclid's lemma (Elements VII, 30): If a prime p divides the product ab of two integers a and b, then p must divide at least one of those integers a and b.

Existence[]

It must be shown that every integer greater than 1 is either prime or a product of primes. First, 2 is prime. Then, by strong induction, assume this is true for all numbers greater than 1 and less than n. If n is prime, there is nothing more to prove. Otherwise, there are integers a and b, where n = ab, and 1 < a ≤ b < n. By the induction hypothesis, a = p1p2...pj and b = q1q2...qk are products of primes. But then n = ab = p1p2...pjq1q2...qk is a product of primes.

Uniqueness[]

Suppose, to the contrary, there is an integer that has two distinct prime factorizations. Let n be the least such integer and write n = p1 p2 ... pj = q1 q2 ... qk, where each pi and qi is prime. (Note j and k are both at least 2.) We see p1 divides q1 q2 ... qk, so p1 divides some qi by Euclid's lemma. Without loss of generality, say p1 divides q1. Since p1 and q1 are both prime, it follows that p1 = q1. Returning to our factorizations of n, we may cancel these two terms to conclude p2 ... pj = q2 ... qk. We now have two distinct prime factorizations of some integer strictly smaller than n, which contradicts the minimality of n.

Uniqueness without Euclid's lemma[]

The fundamental theorem of arithmetic can also be proved without using Euclid's lemma.[10] The proof that follows is inspired by Euclid's original version of the Euclidean algorithm.

Assume that is the smallest positive integer which is the product of prime numbers in two different ways. Incidentally, this implies that , if it exists, must be a composite number greater than . Now, say

Every must be distinct from every Otherwise, if say then there would exist some positive integer that is smaller than s and has two distinct prime factorizations. One may also suppose that by exchanging the two factorizations, if needed.

Setting and one has It follows that

As the positive integers less than s have been supposed to have a unique prime factorization, must occur in the factorization of either or Q. The latter case is impossible, as Q, being smaller than s, must have a unique prime factorization, and differs from every The former case is also impossible, as, if is a divisor of it must be also a divisor of which is impossible as and are distinct primes.

Therefore, there cannot exist a smallest integer with more than a single distinct prime factorization. Every positive integer must either be a prime number itself, which would factor uniquely, or a composite that also factors uniquely into primes, or in the case of the integer , not factor into any prime.

Generalizations[]

The first generalization of the theorem is found in Gauss's second monograph (1832) on biquadratic reciprocity. This paper introduced what is now called the ring of Gaussian integers, the set of all complex numbers a + bi where a and b are integers. It is now denoted by He showed that this ring has the four units ±1 and ±i, that the non-zero, non-unit numbers fall into two classes, primes and composites, and that (except for order), the composites have unique factorization as a product of primes.[11]

Similarly, in 1844 while working on cubic reciprocity, Eisenstein introduced the ring , where is a cube root of unity. This is the ring of Eisenstein integers, and he proved it has the six units and that it has unique factorization.

However, it was also discovered that unique factorization does not always hold. An example is given by . In this ring one has[12]

Examples like this caused the notion of "prime" to be modified. In it can be proven that if any of the factors above can be represented as a product, for example, 2 = ab, then one of a or b must be a unit. This is the traditional definition of "prime". It can also be proven that none of these factors obeys Euclid's lemma; for example, 2 divides neither (1 + √−5) nor (1 − √−5) even though it divides their product 6. In algebraic number theory 2 is called irreducible in (only divisible by itself or a unit) but not prime in (if it divides a product it must divide one of the factors). The mention of is required because 2 is prime and irreducible in Using these definitions it can be proven that in any integral domain a prime must be irreducible. Euclid's classical lemma can be rephrased as "in the ring of integers every irreducible is prime". This is also true in and but not in

The rings in which factorization into irreducibles is essentially unique are called unique factorization domains. Important examples are polynomial rings over the integers or over a field, Euclidean domains and principal ideal domains.

In 1843 Kummer introduced the concept of ideal number, which was developed further by Dedekind (1876) into the modern theory of ideals, special subsets of rings. Multiplication is defined for ideals, and the rings in which they have unique factorization are called Dedekind domains.

There is a version of unique factorization for ordinals, though it requires some additional conditions to ensure uniqueness.

See also[]

- Integer factorization – Decomposition of an integer into a product

- Prime signature – Multiset of prime exponents in a prime factorization

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gauss & Clarke (1986, Art. 16)

- ^ Gauss & Clarke (1986, Art. 131)

- ^ Long (1972, p. 44)

- ^ Pettofrezzo & Byrkit (1970, p. 53)

- ^ Hardy & Wright (2008, Thm 2)

- ^ Weil (2007, p. 5): "Even in Euclid, we fail to find a general statement about the uniqueness of the factorization of an integer into primes; surely he may have been aware of it, but all he has is a statement (Eucl.IX.I4) about the l.c.m. of any number of given primes."

- ^ Long (1972, p. 45)

- ^ Pettofrezzo & Byrkit (1970, p. 55)

- ^ Hardy & Wright (2008, § 1.2)

- ^ Dawson, John W. (2015). Why Prove it Again? Alternative Proofs in Mathematical Practice. Springer. p. 45. ISBN 9783319173689.

- ^ Gauss, BQ, §§ 31–34

- ^ Hardy & Wright (2008, § 14.6)

References[]

The Disquisitiones Arithmeticae has been translated from Latin into English and German. The German edition includes all of his papers on number theory: all the proofs of quadratic reciprocity, the determination of the sign of the Gauss sum, the investigations into biquadratic reciprocity, and unpublished notes.

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich; Clarke, Arthur A. (translator into English) (1986), Disquisitiones Arithemeticae (Second, corrected edition), New York: Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-96254-2

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich; Maser, H. (translator into German) (1965), Untersuchungen über hohere Arithmetik (Disquisitiones Arithemeticae & other papers on number theory) (Second edition), New York: Chelsea, ISBN 0-8284-0191-8

The two monographs Gauss published on biquadratic reciprocity have consecutively numbered sections: the first contains §§ 1–23 and the second §§ 24–76. Footnotes referencing these are of the form "Gauss, BQ, § n". Footnotes referencing the Disquisitiones Arithmeticae are of the form "Gauss, DA, Art. n".

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1828), Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum, Commentatio prima, Göttingen: Comment. Soc. regiae sci, Göttingen 6

- Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1832), Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum, Commentatio secunda, Göttingen: Comment. Soc. regiae sci, Göttingen 7

These are in Gauss's Werke, Vol II, pp. 65–92 and 93–148; German translations are pp. 511–533 and 534–586 of the German edition of the Disquisitiones.

- Baker, Alan (1984), A Concise Introduction to the Theory of Numbers, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-28654-1

- Euclid (1956), The thirteen books of the Elements, 2 (Books III-IX), Translated by Thomas Little Heath (Second Edition Unabridged ed.), New York: Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-60089-5

- Hardy, G. H.; Wright, E. M. (2008) [1938]. An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers. Revised by D. R. Heath-Brown and J. H. Silverman. Foreword by Andrew Wiles. (6th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921986-5. MR 2445243. Zbl 1159.11001.

- A. Kornilowicz; P. Rudnicki (2004), "Fundamental theorem of arithmetic", , 12 (2): 179–185

- Long, Calvin T. (1972), Elementary Introduction to Number Theory (2nd ed.), Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company, LCCN 77-171950.

- Pettofrezzo, Anthony J.; Byrkit, Donald R. (1970), Elements of Number Theory, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, LCCN 77-81766.

- Riesel, Hans (1994), Prime Numbers and Computer Methods for Factorization (second edition), Boston: Birkhäuser, ISBN 0-8176-3743-5

- Weil, André (2007) [1984]. Number Theory: An Approach through History from Hammurapi to Legendre. Modern Birkhäuser Classics. Boston, MA: Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-0-817-64565-6.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Abnormal number". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic". MathWorld.

External links[]

- Why isn’t the fundamental theorem of arithmetic obvious?

- GCD and the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic at cut-the-knot.

- PlanetMath: Proof of fundamental theorem of arithmetic

- Fermat's Last Theorem Blog: Unique Factorization, a blog that covers the history of Fermat's Last Theorem from Diophantus of Alexandria to the proof by Andrew Wiles.

- "Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic" by Hector Zenil, Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.

- Grime, James. "1 and Prime Numbers". Numberphile. Brady Haran.

- Theorems about prime numbers

- Uniqueness theorems

![\mathbb {Z} [i].](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/03900897cdf515bbbc52879377653a871b9efc06)

![\mathbb {Z} [\omega ]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7ae955a9a0d0f342fc73aaafe28af604d23267f7)

![\mathbb {Z} [{\sqrt {-5}}]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a37499ef27234d8a67a65932184280bb17301312)

![\mathbb {Z} [i]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9ffa94e9e2e6d9e5e5373d5fafb954b902743fde)

![\mathbb {Z} [\omega ],](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0645ae396d9c6f03fd33508a10a838bd30741db0)

![\mathbb {Z} [{\sqrt {-5}}].](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/b61cb2c7c704f5007aa548b630b3a05fa032f621)