Gavaksha

In Indian architecture, gavaksha or chandrashala (kudu in Tamil, also nāsī)[1] are the terms most often used to describe the motif centred on an ogee, circular or horseshoe arch that decorates many examples of Indian rock-cut architecture and later Indian structural temples and other buildings. In its original form, the arch is shaped like the cross-section of a barrel vault. It is called a chaitya arch when used on the facade of a chaitya hall, around the single large window.[2] In later forms it develops well beyond this type, and becomes a very flexible unit, "the most common motif of Hindu temple architecture".[3] Gavākṣha (or gavaksa) is a Sanskrit word which means "bull's or cow's eye". In Hindu temples, their role is envisioned as symbolically radiating the light and splendour of the central icon in its sanctum. Alternatively, they are described as providing a window for the deity to gaze out into the world.[4]

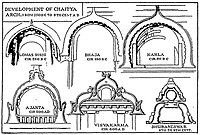

Like the whole of the classic chaitya, the form originated in the shape of the wooden thatched roofs of buildings, none of which have survived; the earliest version replicating such roofs in stone is at the entrance to the non-Buddhist Lomas Rishi Cave, one of the man-made Barabar Caves in Bihar.[5]

The "chaitya arch" around the large window above the entrance frequently appears repeated as a small motif in decoration, and evolved versions continue into Hindu decoration, long after actual chaityas had ceased to be built.[6] In these cases it can become an elaborate cartouche-like frame, spreading rather wide, around a circular or semi-circular medallion, which may contain a sculpture of a figure or head. An early stage is shown in the entrance to Cave 9 at the Ajanta Caves, where the chaitya arch window frame is repeated several times as a decorative motif. Here, and in many similar early examples, the interior of the arch in the motif contains low relief lattice imitating receding roof timbers (purlins).

First stage[]

The arched gable-end form seen at the Lomas Rishi Cave and other sites appears as a feature of both sacred and secular buildings represented in reliefs from early Buddhist sites in India, and was evidently widely used for roofs made from plant materials in ancient Indian architecture.[7] Simple versions of similar structures remain in use today by the Toda people of the Nilgiri Hills.[8]

The rock-cut Lomas Rishi Cave was excavated during the reign of Ashoka in the Maurya Empire in the 3rd century BC, for the Ajivikas, a non-Buddhist religious and philosophical group of the period. A band below the arch contains a lattice in relief, presumably representing the ceiling of a thatched roof. Below that is a curved relief of a line of elephants. The entrance leads into the side of the hall, so unlike most later window frame examples, the arch bears no great relationship to the space it leads into. The immediately neighbouring cave in the same rock face has a plain undecorated recess at the entrance, which originally may have held a porch of similar design in plant materials.[9]

Early rock-cut chaitya halls use the same ogee shape for the main window needed to illuminate the interior, and often also have small relief window motifs as decoration. In these the inside of the arch has a series of square-ended projections representing the joists, and inside that a curving lattice in low relief that represents the receding roof timbers of the inside of a notional building. At the bottom, a small area, more or less semi-circular, represents the far wall of the structure, and may be plain (e.g. Bhaja Caves over side galleries), show a different lattice pattern (e.g. Bhaja Caves main front), Pandavleni Caves cave 18, above), or a decorative motif (e.g. Cave 9, Ajanta, Pandavleni Caves cave 18, over doorway). Often the areas around these window or gable motifs have bands of latticework, apparently representing lattice railings, similar to those shown edging the balconies and loggias of the fort-palace in the relief of Kusinagara in the War over the Buddha's Relics, South Gate, Stupa no. 1, Sanchi. This is especially the case at the Bedse Caves,[10] in an early example of what James Fergusson noted in the nineteenth century: "Everywhere ... in India architectural decoration is made up of small models of large buildings".[11]

At the entrance to Cave 19 at Ajanta, four horizontal zones of the decoration use repeated "chaitya arch" motifs on an otherwise plain band (two on the projecting porch, and two above). There is a head inside each arch. Early examples include Ellora Caves 10, Ajanta Caves 9 and 19 and Varaha Cave Temple at Mamallapuram.[12]

Conjectural reconstruction of the main gate of Kusinagara circa 500 BCE adapted from this relief at Sanchi.

Interior of a rock-cut chaitya hall, Bhaja Caves, the ribs in wood

Chaitya arch motif in a vihara at Bedse Caves

Side wall inside the chaitya at Bedse Caves

Development of the Chaitya Arch from Lomas Rishi Cave, from a book by Percy Brown.

Scene on the Bodh Gaya railings (replica), representing a building

Exterior of chaitya hall, Cave 9, Ajanta Caves, 1st century BCE. The chaitya arch window frame is repeated several times as a decorative motif.

Chaitya arch motif in a vihara at Ajanta

Entrance to Cave 19, Ajanta Caves, late 5th century, also with four zones using the "chaitya arch" motif

Modern hut of the Toda people

Later development[]

By around 650, the time of the last rock-cut chaitya hall, Cave 10 at Ellora, the window on the facade has developed considerably. The main window is smaller, and now bears no relation to the roof inside (which still has the traditional ribs). It has only two of the traditional projections imitating purlin beam-ends, and a wide decorative frame that spreads over several times the width of the actual window opening. Two doors to the sides have pediments with "split and superimposed" blind gavakshas, also with wide frames. This was to be the style of gavaksha that had already been widely adopted for the decoration of Hindu and Jain temples, and is seen in simplified form in the Buddhist Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya, and the Hindu Dashavatara Temple, Deogarh.[13]

Also in the 7th century, the sukanasa developed. This is a very large developed gavaksha motif fixed on the outside of the temple tower over its entrance, normally standing vertical, although the tower slopes inwards.[14]

By the end of the 7th century, and perhaps earlier, the entire faces of large shikhara towers or other surfaces could be taken up by grids of interlocking gavaksha motifs, often called "gavaksha mesh" or honeycomb.[15] Early examples include the Buddhist shikhara tower at the Mahabodhi Temple, Bodh Gaya, where the motifs cover most of the surface but do not actually interlock. This is of the 6th century at the latest, but perhaps restoring a design of as early as the 2nd or 3rd century.[16] Cave 15 at Ellora, complete by 730 if not before, and perhaps begun as a Buddhist excavation, may be one of the earliest examples of the full style.[17] The motif spread to South India, for example the 7th and 8th century temples at Pattadakal in Karnataka.

Gop Temple in Gujarat, probably from the 6th century, is the largest and finest of a group of early temples in a distinct local style. The bare castle-like appearance of the central square tower today probably does not reflect the original design, as the upper parts of the structure around it are missing. Above the plain walls the sloping top includes three large gavakshas on each face, two below and one above, which are unusual in actually being open, rather than in shallow relief, like almost all later gavakshas. Originally statues stood behind them, of which very little now remains.[18]

Gavakshas are prominent in some temples of the 8th century group on the Dieng plateau in central Java, among the earliest monumental Hindu temples in modern Indonesia.[19]

Nāsīs of the south[]

Adam Hardy distinguishes between the gavaksha, which he largely restricts to the Nagara architecture of the north, and its cousin in the Dravidian architecture of the south, the nāsī ("kudu" in Tamil). He allows an early period of "gradual differentiation" as the nāsī evolves from the gavaksha, the first to appear. In a detailed analysis of the parts of the motif, he points to several differences of form. Among other characteristics of the nāsī, the motif has no frame at the base, the interior of the window is often blank (perhaps originally painted), and there is often a kirtimukha head at the top of the motif. In general, the form is less linear, and more heavily ornamented.[20]

North roof of Gop Surya temple, Gujarat, c. late 6th / early 7th century

Two chaitya arch motifs on top of each other. Hindu temple, Osian, Jodhpur, 8th century.

Gavaksha at Nalanda

Sukanasa with Shiva Nataraja and small gavaksha motifs, Jambulingeshwara Temple, Pattadakal, 7th-8th century.[21]

The decoration of the 9th-century Kasivisvanatha temple at Pattadakal includes gavakshas in several forms

Elaborated gavakshas at the early 9th-century Jain Cave 32 at Ellora

"Honeycomb" of gavakshas on the shikhara of the Vamana Temple, Khajuraho, 1050-75

Candi Bima temple, Dieng temples, Java, 8th century

Bhima Ratha (Five Rathas), Mahabalipuram

Notes[]

- ^ properly: candraśālās, gavākṣa, kūḍu. Harle, 49, 166, 276. Harle restricts use of candraśālā to examples from the Gupta period, when contemporary texts use that term.

- ^ "Glossary of Indian Art". Retrieved 2015-05-18.

- ^ Harle, 48

- ^ Elgood (2000), 103

- ^ Harle, 48; Michell, 217–218

- ^ Harle, 48

- ^ Hardy, 38; Harle, 43–48

- ^ Gowans, Alan. The Art Bulletin, vol. 38, no. 2, 1956, pp. 127–129, [www.jstor.org/stable/3047649 JSTOR] (Review of Zimmer)

- ^ Harle, 48; Michell, 217–218

- ^ Harle, 48, 54

- ^ Quoted in Hardy, 18

- ^ Harle, 276

- ^ Harle, 112, 132, 201; Hardy, 40

- ^ Kramrisch, 240–241; Harle, 140

- ^ Harle, 134, 140

- ^ Harle, 201

- ^ Harle, 134

- ^ Harle, 136–138

- ^ Michell (1988), 160–161

- ^ Hardy, 101–103

- ^ Michell, 105

References[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chaitya arch motifs. |

- Elgood, Heather, Hinduism and the Religious Arts, 2000, A&C Black, ISBN 0304707392, 9780304707393, google books

- Hardy, Adam, Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation : the Karṇāṭa Drāviḍa Tradition, 7th to 13th Centuries, 1995, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 8170173124, 9788170173120, google books

- Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

- Kramrisch, Stella, The Hindu Temple, Volume 1, 1996 (originally 1946), ISBN 8120802225, 9788120802223, google books

- Michell, George, The Penguin Guide to the Monuments of India, Volume 1: Buddhist, Jain, Hindu, 1989, Penguin Books, ISBN 0140081445

- Hindu temple architecture

- Buddhist architecture

- Ornaments (architecture)