Ajanta Caves

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

The Ajanta Caves | |

| Location | Aurangabad District, Maharashtra State, India |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, vi |

| Reference | 242 |

| Inscription | 1983 (7th Session) |

| Area | 8,242 ha |

| Buffer zone | 78,676 ha |

| Coordinates | 20°33′12″N 75°42′01″E / 20.55333°N 75.70028°ECoordinates: 20°33′12″N 75°42′01″E / 20.55333°N 75.70028°E |

Location of Ajanta Caves in India | |

| Pilgrimage to |

| Buddha's Holy Sites |

|---|

|

| The Four Main Sites |

| Four Additional Sites |

| Other Sites |

|

| Later Sites |

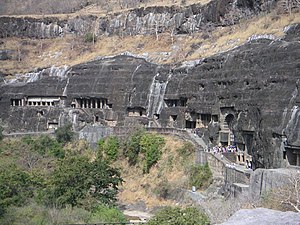

The Buddhist Caves in Ajanta are approximately 30 rock-cut Buddhist cave monuments dating from the 2nd century BCE to about 480 CE in the Aurangabad district of Maharashtra state in India.[1][note 1] The caves include paintings and rock-cut sculptures described as among the finest surviving examples of ancient Indian art, particularly expressive paintings that present emotions through gesture, pose and form.[3][4][5]

They are universally regarded as masterpieces of Buddhist religious art. The caves were built in two phases, the first starting around the 2nd century BCE and the second occurring from 400 to 650 CE, according to older accounts, or in a brief period of 460–480 CE according to later scholarship.[6] The site is a protected monument in the care of the Archaeological Survey of India,[7] and since 1983, the Ajanta Caves have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Ajanta Caves constitute ancient monasteries and worship-halls of different Buddhist traditions carved into a 75-metre (246 ft) wall of rock.[8][9] The caves also present paintings depicting the past lives [10] and rebirths of the Buddha, pictorial tales from Aryasura's Jatakamala, and rock-cut sculptures of Buddhist deities.[8][11][12] Textual records suggest that these caves served as a monsoon retreat for monks, as well as a resting site for merchants and pilgrims in ancient India.[8] While vivid colours and mural wall-painting were abundant in Indian history as evidenced by historical records, Caves 16, 17, 1 and 2 of Ajanta form the largest corpus of surviving ancient Indian wall-painting.[13]

The Ajanta Caves are mentioned in the memoirs of several medieval-era Chinese Buddhist travellers to India and by a Mughal-era official of Akbar era in the early 17th century.[14] They were covered by jungle until accidentally "discovered" and brought to Western attention in 1819 by a colonial British officer Captain John Smith on a tiger-hunting party.[15] The caves are in the rocky northern wall of the U-shaped gorge of the river Waghur,[16] in the Deccan plateau.[17][18] Within the gorge are a number of waterfalls, audible from outside the caves when the river is high.[19]

With the Ellora Caves, Ajanta is one of the major tourist attractions of Maharashtra. It is about 6 kilometres (3.7 miles) from Fardapur, 59 kilometres (37 miles) from the city of Jalgaon, Maharashtra, India, 104 kilometres (65 miles) from the city of Aurangabad, and 350 kilometres (220 miles) east-northeast of Mumbai.[8][20] Ajanta is 100 kilometres (62 miles) from the Ellora Caves, which contain Hindu, Jain and Buddhist caves, the last dating from a period similar to Ajanta. The Ajanta style is also found in the Ellora Caves and other sites such as the Elephanta Caves, Aurangabad Caves, Shivleni Caves and the cave temples of Karnataka.[21]

History[]

The Ajanta Caves are generally agreed to have been made in two distinct phases, the first during the 2nd century BCE to 1st century CE, and a second several centuries later.[22][23][24]

The caves consist of 36 identifiable foundations,[8] some of them discovered after the original numbering of the caves from 1 through 29. The later-identified caves have been suffixed with the letters of the alphabet, such as 15A, identified between originally numbered caves 15 and 16.[25] The cave numbering is a convention of convenience, and does not reflect the chronological order of their construction.[26]

Caves of the first (Satavahana) period[]

The earliest group consists of caves 9, 10, 12, 13 and 15A. The murals in these caves depict stories from the Jatakas.[26] Later caves reflect the artistic influence of the Gupta period,[26] but there are differing opinions on which century in which the early caves were built.[27][28] According to Walter Spink, they were made during the period 100 BCE to 100 CE, probably under the patronage of the Hindu Satavahana dynasty (230 BCE – c. 220 CE) who ruled the region.[29][30] Other datings prefer the period of the Maurya Empire (300 BCE to 100 BCE).[31] Of these, caves 9 and 10 are stupa containing worship halls of chaitya-griha form, and caves 12, 13, and 15A are vihāras (see the architecture section below for descriptions of these types).[25] The first Satavahana period caves lacked figurative sculpture, emphasizing the stupa instead.

According to Spink, once the Satavahana period caves were made, the site was not further developed for a considerable period until the mid-5th century.[32] However, the early caves were in use during this dormant period, and Buddhist pilgrims visited the site, according to the records left by Chinese pilgrim Faxian around 400 CE.[25]

Caves of the later, or Vākāṭaka, period[]

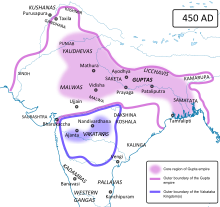

The second phase of construction at the Ajanta Caves site began in the 5th century. For a long time it was thought that the later caves were made over an extended period from the 4th to the 7th centuries CE,[33] but in recent decades a series of studies by the leading expert on the caves, Walter M. Spink, have argued that most of the work took place over the very brief period from 460 to 480 CE,[32] during the reign of Hindu Emperor Harishena of the Vākāṭaka dynasty.[34][35][36] This view has been criticised by some scholars,[37] but is now broadly accepted by most authors of general books on Indian art, for example, Huntington and Harle.

The second phase is attributed to the theistic Mahāyāna,[26] or Greater Vehicle tradition of Buddhism.[38][39] Caves of the second period are 1–8, 11, 14–29, some possibly extensions of earlier caves. Caves 19, 26, and 29 are chaitya-grihas, the rest viharas. The most elaborate caves were produced in this period, which included some refurbishing and repainting of the early caves.[40][26][41]

Spink states that it is possible to establish dating for this period with a very high level of precision; a fuller account of his chronology is given below.[42] Although debate continues, Spink's ideas are increasingly widely accepted, at least in their broad conclusions. The Archaeological Survey of India website still presents the traditional dating: "The second phase of paintings started around 5th–6th centuries A.D. and continued for the next two centuries".

According to Spink, the construction activity at the incomplete Ajanta Caves was abandoned by wealthy patrons in about 480 CE, a few years after the death of Harishena. However, states Spink, the caves appear to have been in use for a period of time as evidenced by the wear of the pivot holes in caves constructed close to 480 CE.[43] The second phase of constructions and decorations at Ajanta corresponds to the very apogee of Classical India, or India's golden age.[44] However, at that time, the Gupta Empire was already weakening from internal political issues and from the assaults of the Hūṇas, so that the Vakatakas were actually one of the most powerful empires in India.[45] Some of the Hūṇas, the Alchon Huns of Toramana, were precisely ruling the neighbouring area of Malwa, at the doorstep of the Western Deccan, at the time the Ajanta caves were made.[46] Through their control of vast areas of northwestern India, the Huns may actually have acted as a cultural bridge between the area of Gandhara and the Western Deccan, at the time when the Ajanta or Pitalkhora caves were being decorated with some designs of Gandharan inspiration, such as Buddhas dressed in robes with abundant folds.[47]

According to Richard Cohen, a description of the caves by 7th-century Chinese traveler Xuanzang and scattered medieval graffiti suggest that the Ajanta Caves were known and probably in use subsequently, but without a stable or steady Buddhist community presence.[14] The Ajanta caves are mentioned in the 17th-century text Ain-i-Akbari by Abu al-Fazl, as twenty four rock-cut cave temples each with remarkable idols.[14]

Colonial era[]

On 28 April 1819 a British officer named John Smith, of the 28th Cavalry, while hunting tigers discovered the entrance to Cave No. 10 when a local shepherd boy guided him to the location and the door. The caves were well known by locals already.[48] Captain Smith went to a nearby village and asked the villagers to come to the site with axes, spears, torches, and drums, to cut down the tangled jungle growth that made entering the cave difficult.[48] He then vandalised the wall by scratching his name and the date over the painting of a bodhisattva. Since he stood on a five-foot high pile of rubble collected over the years, the inscription is well above the eye-level gaze of an adult today.[49] A paper on the caves by William Erskine was read to the Bombay Literary Society in 1822.[50]

Within a few decades, the caves became famous for their exotic setting, impressive architecture, and above all their exceptional and unique paintings. A number of large projects to copy the paintings were made in the century after rediscovery. In 1848, the Royal Asiatic Society established the "Bombay Cave Temple Commission" to clear, tidy and record the most important rock-cut sites in the Bombay Presidency, with John Wilson as president. In 1861 this became the nucleus of the new Archaeological Survey of India.[51]

During the colonial era, the Ajanta site was in the territory of the princely state of the Hyderabad and not British India.[52] In the early 1920s, Mir Osman Ali Khan the last Nizam of Hyderabad appointed people to restore the artwork, converted the site into a museum and built a road to bring tourists to the site for a fee. These efforts resulted in early mismanagement, states Richard Cohen, and hastened the deterioration of the site. Post-independence, the state government of Maharashtra built arrival, transport, facilities, and better site management. The modern Visitor Center has good parking facilities and public conveniences and ASI operated buses run at regular intervals from Visitor Center to the caves.[52]

The Nizam's Director of Archaeology obtained the services of two experts from Italy, Professor Lorenzo Cecconi, assisted by Count Orsini, to restore the paintings in the caves.[53] The Director of Archaeology for the last Nizam of Hyderabad said of the work of Cecconi and Orsini:

The repairs to the caves and the cleaning and conservation of the frescoes have been carried out on such sound principles and in such a scientific manner that these matchless monuments have found a fresh lease of life for at least a couple of centuries.[54]

Despite these efforts, later neglect led to the paintings degrading in quality once again.[54]

Since 1983, Ajanta caves have been listed among the UNESCO World Heritage Sites of India. The Ajanta Caves, along with the Ellora Caves, have become the most popular tourist destination in Maharashtra, and are often crowded at holiday times, increasing the threat to the caves, especially the paintings.[55] In 2012, the Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation announced plans to add to the ASI visitor centre at the entrance complete replicas of caves 1, 2, 16 & 17 to reduce crowding in the originals, and enable visitors to receive a better visual idea of the paintings, which are dimly-lit and hard to read in the caves.[56]

Sites and monasteries[]

Sites[]

The caves are carved out of flood basalt rock of a cliff, part of the Deccan Traps formed by successive volcanic eruptions at the end of the Cretaceous geological period. The rock is layered horizontally, and somewhat variable in quality.[57] This variation within the rock layers required the artists to amend their carving methods and plans in places. The inhomogeneity in the rock has also led to cracks and collapses in the centuries that followed, as with the lost portico to cave 1. Excavation began by cutting a narrow tunnel at roof level, which was expanded downwards and outwards; as evidenced by some of the incomplete caves such as the partially-built vihara caves 21 through 24 and the abandoned incomplete cave 28.[58]

The sculpture artists likely worked at both excavating the rocks and making the intricate carvings of pillars, roof, and idols; further, the sculpture and painting work inside a cave were integrated parallel tasks.[59] A grand gateway to the site was carved, at the apex of the gorge's horseshoe between caves 15 and 16, as approached from the river, and it is decorated with elephants on either side and a nāga, or protective Naga (snake) deity.[60][61] Similar methods and application of artist talent is observed in other cave temples of India, such as those from Hinduism and Jainism. These include the Ellora Caves, Ghototkacha Caves, Elephanta Caves, Bagh Caves, Badami Caves, Aurangabad Caves[62] and Shivleni Caves.

The caves from the first period seem to have been paid for by a number of different patrons to gain merit, with several inscriptions recording the donation of particular portions of a single cave. The later caves were each commissioned as a complete unit by a single patron from the local rulers or their court elites, again for merit in Buddhist afterlife beliefs as evidenced by inscriptions such as those in Cave 17.[63] After the death of Harisena, smaller donors motivated by getting merit added small "shrinelets" between the caves or add statues to existing caves, and some two hundred of these "intrusive" additions were made in sculpture, with a further number of intrusive paintings, up to three hundred in cave 10 alone.[64]

Monasteries[]

The majority of the caves are vihara halls with symmetrical square plans. To each vihara hall are attached smaller square dormitory cells cut into the walls.[65] A vast majority of the caves were carved in the second period, wherein a shrine or sanctuary is appended at the rear of the cave, centred on a large statue of the Buddha, along with exuberantly detailed reliefs and deities near him as well as on the pillars and walls, all carved out of the natural rock.[66] This change reflects the shift from Hinayana to Mahāyāna Buddhism. These caves are often called monasteries.

The central square space of the interior of the viharas is defined by square columns forming a more-or-less square open area. Outside this are long rectangular aisles on each side, forming a kind of cloister. Along the side and rear walls are a number of small cells entered by a narrow doorway; these are roughly square, and have small niches on their back walls. Originally they had wooden doors.[67] The centre of the rear wall has a larger shrine-room behind, containing a large Buddha statue.

The viharas of the earlier period are much simpler, and lack shrines.[21][68] Spink places the change to a design with a shrine to the middle of the second period, with many caves being adapted to add a shrine in mid-excavation, or after the original phase.[69]

The plan of Cave 1 shows one of the largest viharas, but is fairly typical of the later group. Many others, such as Cave 16, lack the vestibule to the shrine, which leads straight off the main hall. Cave 6 is two viharas, one above the other, connected by internal stairs, with sanctuaries on both levels.[70]

Cave 12 plan: an early type of vihara (1st century BCE) without internal shrine

Cave 1 plan, a monastery known for its paintings[71]

Cave 6: a two-storey monastery with "Miracle of Sravasti" and "Temptation of Mara" painted[72]

Cave 16: a monastery featuring two side aisles[72]

Worship halls[]

The other type of main hall architecture is the narrower rectangular plan with high arched ceiling type chaitya-griha – literally, "the house of stupa". This hall is longitudinally divided into a nave and two narrower side aisles separated by a symmetrical row of pillars, with a stupa in the apse.[73][74] The stupa is surrounded by pillars and concentric walking space for circumambulation. Some of the caves have elaborate carved entrances, some with large windows over the door to admit light. There is often a colonnaded porch or verandah, with another space inside the doors running the width of the cave. The oldest worship halls at Ajanta were built in the 2nd to 1st century BCE, the newest ones in the late 5th century CE, and the architecture of both resembles the architecture of a Christian church, but without the crossing or chapel chevette.[75] The Ajanta Caves follow the Cathedral-style architecture found in still older rock-cut cave carvings of ancient India, such as the Lomas Rishi Cave of the Ajivikas near Gaya in Bihar dated to the 3rd century BCE.[76] These chaitya-griha are called worship or prayer halls.[77][78]

The four completed chaitya halls are caves 9 and 10 from the early period, and caves 19 and 26 from the later period of construction. All follow the typical form found elsewhere, with high ceilings and a central "nave" leading to the stupa, which is near the back, but allows walking behind it, as walking around stupas was (and remains) a common element of Buddhist worship (pradakshina). The later two have high ribbed roofs carved into the rock, which reflect timber forms,[79] and the earlier two are thought to have used actual timber ribs and are now smooth, the original wood presumed to have perished.[80] The two later halls have a rather unusual arrangement (also found in Cave 10 at Ellora) where the stupa is fronted by a large relief sculpture of the Buddha, standing in Cave 19 and seated in Cave 26.[21][68] Cave 29 is a late and very incomplete chaitya hall.[81]

The form of columns in the work of the first period is very plain and un-embellished, with both chaitya halls using simple octagonal columns, which were later painted with images of the Buddha, people and monks in robes. In the second period columns were far more varied and inventive, often changing profile over their height, and with elaborate carved capitals, often spreading wide. Many columns are carved over all their surface with floral motifs and Mahayana deities, some fluted and others carved with decoration all over, as in cave 1.[82][83]

Cave 10: a worship hall with Jataka tales-related art (1st century BCE)[84]

Cave 9: a worship hall with early paintings and animal friezes (1st century CE)[84]

Cave 19: known for its figures of the Buddha, Kubera and other arts (5th century CE)[84]

Cave 19: another view (5th century CE)

Paintings[]

The paintings in the Ajanta caves predominantly narrate the Jataka tales. These are Buddhist legends describing the previous births of the Buddha. These fables embed ancient morals and cultural lores that are also found in the fables and legends of Hindu and Jain texts. The Jataka tales are exemplified through the life example and sacrifices that the Buddha made in hundreds of his past incarnations, where he is depicted as having been reborn as an animal or human.[85][86][87]

Mural paintings survive from both the earlier and later groups of caves. Several fragments of murals preserved from the earlier caves (Caves 10 and 11) are effectively unique survivals of ancient painting in India from this period, and "show that by Sātavāhana times, if not earlier, the Indian painters had mastered an easy and fluent naturalistic style, dealing with large groups of people in a manner comparable to the reliefs of the Sāñcī toraņa crossbars".[88] Some connections with the art of Gandhara can also be noted, and there is evidence of a shared artistic idiom.[89]

Four of the later caves have large and relatively well-preserved mural paintings which, states James Harle, "have come to represent Indian mural painting to the non-specialist",[88] and represent "the great glories not only of Gupta but of all Indian art".[90] They fall into two stylistic groups, with the most famous in Caves 16 and 17, and apparently later paintings in Caves 1 and 2. The latter group were thought to be a century or later than the others, but the revised chronology proposed by Spink would place them in the 5th century as well, perhaps contemporary with it in a more progressive style, or one reflecting a team from a different region.[91] The Ajanta frescos are classical paintings and the work of confident artists, without cliches, rich and full. They are luxurious, sensuous and celebrate physical beauty, aspects that early Western observers felt were shockingly out of place in these caves presumed to be meant for religious worship and ascetic monastic life.[92]

The paintings are in "dry fresco", painted on top of a dry plaster surface rather than into wet plaster.[93] All the paintings appear to be the work of painters supported by discriminating connoisseurship and sophisticated patrons from an urban atmosphere. We know from literary sources that painting was widely practised and appreciated in the Gupta period. Unlike much Indian mural painting, compositions are not laid out in horizontal bands like a frieze, but show large scenes spreading in all directions from a single figure or group at the centre.[92] The ceilings are also painted with sophisticated and elaborate decorative motifs, many derived from sculpture.[91] The paintings in cave 1, which according to Spink was commissioned by Harisena himself, concentrate on those Jataka tales which show previous lives of the Buddha as a king, rather than as deer or elephant or another Jataka animal. The scenes depict the Buddha as about to renounce the royal life.[94]

In general the later caves seem to have been painted on finished areas as excavating work continued elsewhere in the cave, as shown in caves 2 and 16 in particular.[95] According to Spink's account of the chronology of the caves, the abandonment of work in 478 after a brief busy period accounts for the absence of painting in places including cave 4 and the shrine of cave 17, the later being plastered in preparation for paintings that were never done.[94]

Cave 2, showing the extensive paint loss of many areas. It was never finished by its artists, and shows Vidhura Jataka.[96]

Section of the mural in Cave 17, the 'coming of Sinhala'. The prince (Prince Vijaya) is seen in both groups of elephants and riders.

Hamsa jâtaka, cave 17: the Buddha as the golden goose in his previous life[99]

Cave 13

Spink's chronology and cave history[]

Walter Spink has over recent decades developed a very precise and circumstantial chronology for the second period of work on the site, which unlike earlier scholars, he places entirely in the 5th century. This is based on evidence such as the inscriptions and artistic style, dating of nearby cave temple sites, comparative chronology of the dynasties, combined with the many uncompleted elements of the caves.[100] He believes the earlier group of caves, which like other scholars he dates only approximately, to the period "between 100 BCE – 100 CE", were at some later point completely abandoned and remained so "for over three centuries". This changed during the Hindu emperor Harishena of the Vakataka Dynasty,[34] who reigned from 460 to his death in 477, who sponsored numerous new caves during his reign. Harisena's rule extended the Central Indian Vakataka Empire to include a stretch of the east coast of India; the Gupta Empire ruled northern India at the same period, and the Pallava dynasty much of the south.[32]

According to Spink, Harisena encouraged a group of associates, including his prime minister Varahadeva and Upendragupta, the sub-king in whose territory Ajanta was, to dig out new caves, which were individually commissioned, some containing inscriptions recording the donation. This activity began in many caves simultaneously about 462. This activity was mostly suspended in 468 because of threats from the neighbouring Asmaka kings. Thereafter work continued on only Caves 1, Harisena's own commission, and 17–20, commissioned by Upendragupta. In 472 the situation was such that work was suspended completely, in a period that Spink calls "the Hiatus", which lasted until about 475, by which time the Asmakas had replaced Upendragupta as the local rulers.[101]

Work was then resumed, but again disrupted by Harisena's death in 477, soon after which major excavation ceased, except at cave 26, which the Asmakas were sponsoring themselves. The Asmakas launched a revolt against Harisena's son, which brought about the end of the Vakataka Dynasty. In the years 478–480 CE major excavation by important patrons was replaced by a rash of "intrusions" – statues added to existing caves, and small shrines dotted about where there was space between them. These were commissioned by less powerful individuals, some monks, who had not previously been able to make additions to the large excavations of the rulers and courtiers. They were added to the facades, the return sides of the entrances, and to walls inside the caves.[102] According to Spink, "After 480, not a single image was ever made again at the site".[103] However, there exists a Rashtrakuta inscription outside of cave 26 dateable to end of seventh or early 8th century, suggesting the caves were not abandoned until then.

Spink does not use "circa" in his dates, but says that "one should allow a margin of error of one year or perhaps even two in all cases".[104]

Hindu and Buddhist sponsorship[]

The Ajanta Caves were built in a period when both the Buddha and the Hindu gods were simultaneously revered in Indian culture. According to Spink and other scholars, the royal Vakataka sponsors of the Ajanta Caves probably worshipped both Hindu and Buddhist gods.[34][105] This is evidenced by inscriptions in which these rulers, who are otherwise known as Hindu devotees, made Buddhist dedications to the caves.[105] According to Spink,

That one could worship both the Buddha and the Hindu gods may well account for Varahadeva's participation here, just as it can explain why the emperor Harisena himself could sponsor the remarkable Cave 1, even though most scholars agree that he was certainly a Hindu, like earlier Vakataka kings.

— Walter Spink, Ajanta: History and Development, Cave by Cave,[105]

A terracotta plaque of Mahishasuramardini, also known as Durga, was also found in a burnt-brick vihara monastery facing the caves on the right bank of the river Waghora that has been recently excavated.[106][107][108] This suggest that the deity was possibly under worship by the artisans.[106][107] According to Yuko Yokoschi and Walter Spink, the excavated artifacts of the 5th century near the site suggest that the Ajanta caves deployed a huge number of builders.[109][110]

Individual caves[]

Cave 1[]

Cave 1 was built on the eastern end of the horseshoe-shaped scarp and is now the first cave the visitor encounters. This cave, when first made, would have been a less prominent position, right at the end of the row. According to Spink, it is one of the last caves to have been excavated, when the best sites had been taken, and was never fully inaugurated for worship by the dedication of the Buddha image in the central shrine. This is shown by the absence of sooty deposits from butter lamps on the base of the shrine image, and the lack of damage to the paintings that would have happened if the garland-hooks around the shrine had been in use for any period of time. Spink states that the Vākāṭaka Emperor Harishena was the benefactor of the work, and this is reflected in the emphasis on imagery of royalty in the cave, with those Jataka tales being selected that tell of those previous lives of the Buddha in which he was royal.[111]

The cliff has a more steep slope here than at other caves, so to achieve a tall grand facade it was necessary to cut far back into the slope, giving a large courtyard in front of the facade. There was originally a columned portico in front of the present facade, which can be seen "half-intact in the 1880s" in pictures of the site, but this fell down completely and the remains, despite containing fine carvings, were carelessly thrown down the slope into the river, from where they have been lost.[112][113]

This cave (35.7 m × 27.6 m)[114] has one of the most elaborate carved façades, with relief sculptures on entablature and ridges, and most surfaces embellished with decorative carving. There are scenes carved from the life of the Buddha as well as a number of decorative motifs. A two-pillared portico, visible in the 19th-century photographs, has since perished. The cave has a frontcourt with cells fronted by pillared vestibules on either side. These have a high plinth level. The cave has a porch with simple cells on both ends. The absence of pillared vestibules on the ends suggests that the porch was not excavated in the latest phase of Ajanta when pillared vestibules had become customary. Most areas of the porch were once covered with murals, of which many fragments remain, especially on the ceiling. There are three doorways: a central doorway and two side doorways. Two square windows were carved between the doorways to brighten the interiors.[115]

Each wall of the hall inside is nearly 40 feet (12 m) long and 20 feet (6.1 m) high. Twelve pillars make a square colonnade inside supporting the ceiling, and creating spacious aisles along the walls. There is a shrine carved on the rear wall to house an impressive seated image of the Buddha, his hands being in the dharmachakrapravartana mudra. There are four cells on each of the left, rear, and the right walls, though due to rock fault there are none at the ends of the rear aisle.[116]

The paintings of Cave 1 cover the walls and the ceilings. They are in a fair state of preservation, although the full scheme was never completed. The scenes depicted are mostly didactic, devotional, and ornamental, with scenes from the Jataka stories of the Buddha's former lives as a bodhisattva, the life of the Gautama Buddha, and those of his veneration. The two most famous individual painted images at Ajanta are the two over-life-size figures of the protective bodhisattvas Padmapani and Vajrapani on either side of the entrance to the Buddha shrine on the wall of the rear aisle (see illustrations above).[117][118] Other significant frescos in Cave 1 include the Sibi, Sankhapala, Mahajanaka, Mahaummagga, and Champeyya Jataka tales. The cave-paintings also show the Temptation of Mara, the miracle of Sravasti where the Buddha simultaneously manifests in many forms, the story of Nanda, and the story of Siddhartha and Yasodhara.[87][119]

The Bodhisattva of compassion Padmapani with lotus[121][123]

Ajanta Cave 1 Group of foreigners on the ceiling

Cave 2[]

Cave 2, adjacent to Cave 1, is known for the paintings that have been preserved on its walls, ceilings, and pillars. It looks similar to Cave 1 and is in a better state of preservation. This cave is best known for its feminine focus, intricate rock carvings and paint artwork yet it is incomplete and lacks consistency.[126][127] One of the 5th-century frescos in this cave also shows children at a school, with those in the front rows paying attention to the teacher, while those in the back row are shown distracted and acting.[128]

Cave 2 (35.7 m × 21.6 m)[114] was started in the 460s, but mostly carved between 475 and 477 CE, probably sponsored and influenced by a woman closely related to emperor Harisena.[129] It has a porch quite different from Cave 1. Even the façade carvings seem to be different. The cave is supported by robust pillars, ornamented with designs. The front porch consists of cells supported by pillared vestibules on both ends.[130]

The hall has four colonnades which are supporting the ceiling and surrounding a square in the center of the hall. Each arm or colonnade of the square is parallel to the respective walls of the hall, making an aisle in between. The colonnades have rock-beams above and below them. The capitals are carved and painted with various decorative themes that include ornamental, human, animal, vegetative, and semi-divine motifs.[130] Major carvings include that of goddess Hariti. She is a Buddhist deity who originally was the demoness of smallpox and a child eater, who the Buddha converted into a guardian goddess of fertility, easy child birth and one who protects babies.[127][128]

The paintings on the ceilings and walls of Cave 2 have been widely published. They depict the Hamsa, Vidhurapandita, Ruru, Kshanti Jataka tales and the Purna Avadhana. Other frescos show the miracle of Sravasti, Ashtabhaya Avalokitesvara and the dream of Maya.[86][87] Just as the stories illustrated in cave 1 emphasise kingship, those in cave 2 show many noble and powerful women in prominent roles, leading to suggestions that the patron was an unknown woman.[58] The porch's rear wall has a doorway in the center, which allows entrance to the hall. On either side of the door is a square-shaped window to brighten the interior.

A scene from Vidurapandita Jataka: the birth of the Buddha[131]

The artworks of Cave 2 are known for their feminine focus, such as these two females[126]

The Miracle of Sravasti[132]

Cave 3[]

Cave 3 is merely a start of an excavation; according to Spink it was begun right at the end of the final period of work and soon abandoned.[133]

This is an incomplete monastery and only the preliminary excavations of pillared veranda exist. The cave was one of the last projects to start at the site. Its date could be ascribed to circa 477 CE[134][full citation needed], just before the sudden death of Emperor Harisena. The work stopped after the scooping out of a rough entrance of the hall.[citation needed]

Cave 4[]

Cave 4, a Vihara, was sponsored by Mathura, likely not a noble or courtly official, rather a wealthy devotee.[135] This is the largest vihara in the inaugural group, which suggests he had immense wealth and influence without being a state official. It is placed at a significantly higher level, possibly because the artists realized that the rock quality at the lower and same level of other caves was poor and they had a better chance of a major vihara at an upper location. Another likely possibility is that the planners wanted to carve into the rock another large cistern to the left courtside for more residents, mirroring the right, a plan implied by the height of the forward cells on the left side.[135]

The Archaeological Survey of India dates it to the 6th century CE.[114] Spink, in contrast, dates this cave's inauguration a century earlier, to about 463 CE, based on construction style and other inscriptions.[135] Cave 4 shows evidence of a dramatic collapse of its ceiling in the central hall, likely in the 6th century, something caused by the vastness of the cave and geological flaws in the rock. Later, the artists attempted to overcome this geological flaw by raising the height of the ceiling through deeper excavation of the embedded basalt lava.[136]

The cave has a squarish plan, houses a colossal image of the Buddha in preaching pose flanked by bodhisattvas and celestial nymphs hovering above. It consists, of a verandah, a hypostylar hall, sanctum with an antechamber and a series of unfinished cells. This monastery is the largest among the Ajanta caves and it measures nearly 970 square metres (10,400 sq ft) (35m × 28m).[114] The door frame is exquisitely sculpted flanking to the right is carved Bodhisattva as reliever of Eight Great Perils. The rear wall of the verandah contains the panel of litany of Avalokiteśvara. The cave's ceiling collapse likely affected its overall plan, caused it being left incomplete. Only the Buddha's statue and the major sculptures were completed, and except for what the sponsor considered most important elements all other elements inside the cave were never painted.[136]

Cave 5[]

Cave 5, an unfinished excavation was planned as a monastery (10.32 × 16.8 m). Cave 5 is devoid of sculpture and architectural elements except the door frame. The ornate carvings on the frame has female figures with mythical makara creatures found in ancient and medieval era Indian arts.[114] The cave's construction was likely initiated about 465 CE but abandoned because the rock has geological flaws. The construction was resumed in 475 CE after Asmakas restarted work at the Ajanta caves, but abandoned again as the artists and sponsor redesigned and focussed on an expanded Cave 6 that abuts Cave 5.[137]

Cave 6[]

Cave 6 is two-storey monastery (16.85 × 18.07 m). It consists of a sanctum, a hall on both levels. The lower level is pillared and has attached cells. The upper hall also has subsidiary cells. The sanctums on both level feature a Buddha in the teaching posture. Elsewhere, the Buddha is shown in different mudras. The lower level walls depict the Miracle of Sravasti and the Temptation of Mara legends.[114][138] Only the lower floor of cave 6 was finished. The unfinished upper floor of cave 6 has many private votive sculptures, and a shrine Buddha.[133]

The lower level of Cave 6 likely was the earliest excavation in the second stage of construction.[72] This stage marked the Mahayana theme and Vakataka renaissance period of Ajanta reconstruction that started about four centuries after the earlier Hinayana theme construction.[72][139] The upper storey was not envisioned in the beginning, it was added as an afterthought, likely around the time when the architects and artists abandoned further work on the geologically-flawed rock of Cave 5 immediately next to it. Both lower and upper Cave 6 show crude experimentation and construction errors.[140] The cave work was most likely in progress between 460 and 470 CE, and it is the first that shows attendant Bodhisattvas.[141] The upper cave construction probably began in 465, progressed swiftly, and much deeper into the rock than the lower level.[142]

The walls and sanctum's door frame of the both levels are intricately carved. These show themes such as makaras and other mythical creatures, apsaras, elephants in different stages of activity, females in waving or welcoming gesture. The upper level of Cave 6 is significant in that it shows a devotee in a kneeling posture at the Buddha's feet, an indication of devotional worship practices by the 5th century.[138][143] The colossal Buddha of the shrine has an elaborate throne back, but was hastily finished in 477/478 CE, when king Harisena died.[144] The shrine antechamber of the cave features an unfinished sculptural group of the Six Buddhas of the Past, of which only five statues were carved.[144] This idea may have been influenced from those in Bagh Caves of Madhya Pradesh.[145]

The most intact painting in Cave 6: Buddha seated in dharma-chakra-mudra[146]

Mahatma Buddha

Cave 7[]

Cave 7 is also a monastery (15.55 × 31.25 m) but a single storey. It consists of a sanctum, a hall with octagonal pillars, and eight small rooms for monks. The sanctum Buddha is shown in preaching posture. There are many art panels narrating Buddhist themes, including those of the Buddha with Nagamuchalinda and Miracle of Sravasti.[114]

Cave 7 has a grand facade with two porticos. The veranda has eight pillars of two types. One has an octagonal base with amalaka and lotus capital. The other lacks a distinctly shaped base, features an octagonal shaft instead with a plain capital.[149] The veranda opens into an antechamber. On the left side in this antechamber are seated or standing sculptures such as those of 25 carved seated Buddhas in various postures and facial expressions, while on the right side are 58 seated Buddha reliefs in different postures, all placed on lotus.[149] These Buddhas and others on the inner walls of the antechamber are a sculptural depiction of the Miracle of Sravasti in Buddhist theology.[150] The bottom row shows two Nagas (serpents with hoods) holding the blooming lotus stalk.[149] The antechamber leads to the sanctum through a door frame. On this frame are carved two females standing on makaras (mythical sea creatures). Inside the sanctum is the Buddha sitting on a lion throne in cross legged posture, surrounded by other Bodhisattva figures, two attendants with chauris[what language is this?] and flying apsaras above.[149]

Perhaps because of faults in the rock, Cave 7 was never taken very deep into the cliff. It consists only of the two porticos and a shrine room with antechamber, with no central hall. Some cells were fitted in.[151] The cave artwork likely underwent revisions and refurbishments over time. The first version was complete by about 469 CE, the myriad Buddhas added and painted a few years later between 476 and 478 CE.[152]

Cave 7 plan (Robert Gill sketch, 1850)[153]

Cave 7: Buddhas on the antechamber left wall (James Burgess sketch, 1880)[150]

Buddhas on the antechamber's right wall[150]

The shallow corridor before the shrine

Cave 8[]

Cave 8 is another unfinished monastery (15.24 × 24.64 m). For many decades in the 20th-century, this cave was used as a storage and generator room.[154] It is at the river level with easy access, relatively lower than other caves, and according to Archaeological Survey of India it is possibly one of the earliest monasteries. Much of its front is damaged, likely from a landslide.[114] The cave excavation proved difficult and probably abandoned after a geological fault consisting of a mineral layer proved disruptive to stable carvings.[154][155]

Spink, in contrast, states that Cave 8 is perhaps the earliest cave from the second period, its shrine an "afterthought". It may well be the oldest Mahayana monastery excavated in India, according to Spink.[151] The statue may have been loose rather than carved from the living rock, as it has now vanished. The cave was painted, but only traces remain.[151]

Cave 9[]

Caves 9 and 10 are the two chaitya or worship halls from the 2nd to 1st century BCE – the first period of construction, though both were reworked upon the end of the second period of construction in the 5th century CE.

Cave 9 (18.24 m × 8.04 m)[114] is smaller than Cave 10 (30.5 m × 12.2 m),[114] but more complex.[156] This has led Spink to the view that Cave 10 was perhaps originally of the 1st century BCE, and cave 9 about a hundred years later. The small "shrinelets" called caves 9A to 9D and 10A also date from the second period. These were commissioned by individuals.[157] Cave 9 arch has remnant profile that suggests that it likely had wooden fittings.[156]

The cave has a distinct apsidal shape, nave, aisle and an apse with an icon, architecture, and plan that reminds one of the cathedrals built in Europe many centuries later. The aisle has a row of 23 pillars. The ceiling is vaulted. The stupa is at the center of the apse, with a circumambulation path around it. The stupa sits on a high cylindrical base. On the left wall of the cave are votaries approaching the stupa, which suggests a devotional tradition.[158][159]

According to Spink, the paintings in this cave, including the intrusive standing Buddhas on the pillars, were added in the 5th century.[160] Above the pillars and also behind the stupa are colorful paintings of the Buddha with Padmapani and Vajrapani next to him, they wear jewels and necklaces, while yogis, citizens and Buddhist bhikshu are shown approaching the Buddha with garlands and offerings, with men wearing dhoti and turbans wrapped around their heads.[161] On the walls are friezes of Jataka tales, but likely from the Hinayana phase of early construction. Some of the panels and reliefs inside as well as outside Cave 10 do not make narrative sense, but are related to Buddhist legends. This lack of narrative flow may be because these were added by different monks and official donors in the 5th century wherever empty space was available.[159] This devotionalism and the worship hall character of this cave is the likely reason why four additional shrinelets 9A, 9B, 9C, and 9D were added between Cave 9 and 10.[159]

Buddha statue on the porch of Cave 9

The apsidal hall with plain hemispherical stupa at apse's center[161]

Pillar paintings

Cave 9: fresco with Buddhas in orange robes and protected by chatra umbrellas

Cave 10[]

Cave 10, a vast prayer hall or Chaitya, is dated to about the 1st century BCE, together with the nearby vihara cave No 12.[163][164] These two caves are thus among the earliest of the Ajanta complex.[163] It has a large central apsidal hall with a row of 39 octagonal pillars, a nave separating its aisle and stupa at the end for worship. The stupa has a pradakshina patha (circumambulatory path).[114][164]

This cave is significant because its scale confirms the influence of Buddhism in South Asia by the 1st century BCE and its continued though declining influence in India through the 5th century CE.[164] Further, the cave includes a number of inscriptions where parts of the cave are "gifts of prasada" by different individuals, which in turn suggests that the cave was sponsored as a community effort rather than a single king or one elite official.[164] Cave 10 is also historically important because in April 1819, a British Army officer John Smith saw its arch and introduced his discovery to the attention of the Western audience.[114]

- Chronology

Several others caves were also built in Western India around the same period under royal sponsorship.[163] It is thought that the chronology of these early Chaitya Caves is as follows: first Cave 9 at Kondivite Caves and then Cave 12 at the Bhaja Caves, which both predate Cave 10 of Ajanta.[165] Then, after Cave 10 of Ajanta, in chronological order: Cave 3 at Pitalkhora, Cave 1 at Kondana Caves, Cave 9 at Ajanta, which, with its more ornate designs, may have been built about a century later,[163] Cave 18 at Nasik Caves, and Cave 7 at Bedse Caves, to finally culminate with the "final perfection" of the Great Chaitya at Karla Caves.[165]

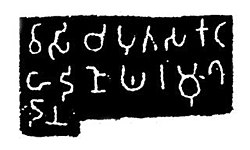

- Inscription

Cave 10 features a Sanskrit inscription in Brahmi script that is archaeologically important.[114] The inscription is the oldest of the Ajanta site, the Brahmi letters being paleographically dated to circa the 2nd century BCE.[166] It reads:[note 2]