Gay Liberation Front

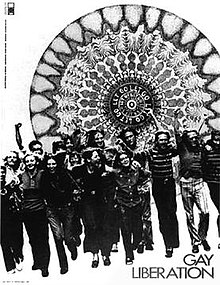

Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was the name of a number of gay liberation groups, the first of which was formed in New York City in 1969, immediately after the Stonewall riots.[1]

United States[]

The United States Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was formed in the aftermath of the Stonewall Riots. The riots are considered by many to be the prime catalyst for the gay liberation movement and the modern fight for LGBT rights in the United States.[2][3]

On 28 June 1969 in Greenwich Village, New York, the New York City police raided the Stonewall Inn, a well known gay bar, located on Christopher Street. Police raids of the Stonewall, and other lesbian and gay bars, were a routine practice at the time, with regular payoffs to dirty cops and organized crime figures an expected part of staying in business.[4] The Stonewall Inn was made up of two former horse stables which had been renovated into one building in 1930. Like all gay bars of the era, it was subject to countless police raids, as LGBT activities and fraternization were still largely illegal. But this time, when the police began arresting patrons, the customers began pelting them with coins, and later, bottles and rocks. The lesbian and gay crowd also freed staff members who had been put into police vans, and the outnumbered officers retreated inside the bar. Soon, the Tactical Patrol Force (TPF), originally trained to deal with war protests, were called in to control the mob, which was now using a parking meter as a battering ram. As the patrol force advanced, the crowd did not disperse, but instead doubled back and re-formed behind the riot police, throwing rocks, shouting "Gay Power!", dancing, and taunting their opposition. For the next several nights, the crowd would return in ever increasing numbers, handing out leaflets and rallying themselves. Soon the word "Stonewall" came to represent fighting for equality in the gay community.[citation needed] And in commemoration, Gay Pride marches are held every year on the anniversary of the riots.

In early July 1969, due in large part to the Stonewall riots in June of that year, discussions in the gay community led to the formation of the Gay Liberation Front. According to scholar Henry Abelove, it was named GLF "in a provocative allusion to the Algerian National Liberation Front and the Vietnamese National Liberation Front.[5]"[6] One of the GLF's first acts was to organize a march to continue the momentum of the Stonewall uprising, and to demand an end to the persecution of homosexuals. The GLF had a broad political platform, denouncing racism and declaring support for various Third World struggles and the Black Panther Party. They took an anti-capitalist stance and attacked the nuclear family and traditional gender roles.

On October 31, 1969, sixty members of the GLF, the Committee for Homosexual Freedom (CHF), and the Gay Guerilla Theatre group staged a protest outside the offices of the San Francisco Examiner in response to a series of news articles disparaging people in San Francisco's gay bars and clubs.[7][8][9][10] The peaceful protest against the Examiner turned tumultuous and was later called "Friday of the Purple Hand" and "Bloody Friday of the Purple Hand".[10][11][12][13][14][15] Examiner employees "dumped a barrel of printers' ink on the crowd from the roof of the newspaper building", according to glbtq.com.[16] Some reports state that it was a barrel of ink poured from the roof of the building.[17] The protesters "used the ink to scrawl slogans on the building walls" and slap purple hand prints "throughout downtown [San Francisco]" resulting in "one of the most visible demonstrations of gay power" according to the Bay Area Reporter.[10][12][15] According to Larry LittleJohn, then president of Society for Individual Rights, "At that point, the tactical squad arrived – not to get the employees who dumped the ink, but to arrest the demonstrators. Somebody could have been hurt if that ink had gotten into their eyes, but the police were knocking people to the ground."[10] The accounts of police brutality include women being thrown to the ground and protesters' teeth being knocked out.[10][18] Inspired by Black Hand extortion methods of Camorra gangsters and the Mafia,[19] some gay and lesbian activists attempted to institute "purple hand" as a warning to stop anti-gay attacks, but with little success.[citation needed] In Turkey, the LGBT rights organization MorEl Eskişehir LGBTT Oluşumu (Purple Hand Eskişehir LGBT Formation), also bears the name of this symbol.[20]

In 1970, several GLF women, such as Martha Shelley, Lois Hart, Karla Jay,[21] and Michela Griffo went on to form the Lavender Menace, a lesbian activist organization.

In 1970, the drag queen caucus of the GLF, including Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, formed the group Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), which focused on providing support for gay prisoners, housing for homeless gay youth and street people, especially other young "street queens".[4][22]

In 1970 "The U.S. Mission" had a permit to use a campground in the Sequoia National Forest. Once it was learned that the group was sponsored by the GLF, the Sequoia National Forest supervisor cancelled the permit, and the campground was closed for the period.[23]

United Kingdom[]

... if we are to succeed in transforming our society we must persuade others of the merits of our ideas, and there is no way we can achieve this if we cannot even persuade those most affected by our oppression to join us in fighting for justice.

We do not intend to ask for anything. We intend to stand firm and assert our basic rights. If this involves violence, it will not be we who initiate this, but those who attempt to stand in our way to freedom.

—GLF Manifesto, 1971[24]

The UK Gay Liberation Front existed between 1970–1973.[25]

Its first meeting was held in the basement of the London School of Economics on 13 October 1970. Bob Mellors and Aubrey Walter had seen the effect of the GLF in the United States and created a parallel movement based on revolutionary politics.[26]

By 1971, the UK GLF was recognized as a political movement in the national press, holding weekly meetings of 200 to 300 people.[27] The GLF Manifesto was published, and a series of high-profile direct actions, were carried out, such as the disruption of the launch of the Church-based morality campaign, Festival of Light.[28]

The disruption of the opening of the 1971 Festival of Light was the best organised GLF action. The first meeting of the Festival of Light was organised by Mary Whitehouse at Methodist Central Hall. Amongst GLF members taking part in this protest were the "Radical Feminists", a group of gender non-conforming males in drag, who invaded and spontaneously kissed each other;[29] others released mice, sounded horns, and unveiled banners, and a contingent dressed as workmen obtained access to the basement and shut off the lights.[30]

Easter 1972 saw the Gay Lib annual conference held in the Guild of Students building at the University of Birmingham.[31]

By 1974, internal disagreements had led to the movement's splintering. Organizations that spun off from the movement included the London Lesbian and Gay Switchboard, Gay News, and Icebreakers. The GLF Information Service continued for a few further years providing gay related resources.[26] GLF branches had been set up in some provincial British towns (e.g., Birmingham, Bradford, Bristol, Leeds, and Leicester) and some survived for a few years longer. The Leicester Gay Liberation Front founded by Jeff Martin was noted for its involvement in the setting up of the local "Gayline", which is still active today and has received funding from the National Lottery. They also carried out a high-profile campaign against the local paper, the Leicester Mercury, which refused to advertise Gayline's services at the time.[32][33]

The papers of the GLF are among the Hall-Carpenter Archives at the London School of Economics.[34]

Several members of the GLF, including Peter Tatchell, continued campaigning beyond the 1970s under the organisation of OutRage!, which was founded in 1990 and dissolved in 2011, using similar tactics to the GLF (such as "zaps"[35] and performance protest[36]) to attract a significant level of media interest and controversy.[citation needed] It was at this point that a divide emerged within the gay activist movement, mainly due to a difference in ideologies,[37] after which a number of groups including Organization for Lesbian and Gay Alliance (OLGA), the Lesbian Avengers, Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, Dykes And Faggots Together (DAFT), Queer Nation, Stonewall (which focused on lobbying tactics) and OutRage! co-existed.[37]

These groups were very influential following the HIV/AIDS pandemic of the 1980s and 1990s and the violence against lesbians and gay men that followed.[37]

Canada[]

The first gay liberation groups identifying with the Gay Liberation Front movement in Canada were in Montreal, Quebec. The Front de libération homosexual (FLH) was formed in November 1970, in response to a call for organised activist groups in the city by the publication .[38] Another factor in the group's formation was police actions against gay establishments in the city after the suspension of civil liberties by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in the fall of 1970.[38] This group was short-lived; they were disbanded after over forty members were charged for failure to procure a liquor license at one of the group's events in 1972.[38]

A Vancouver, British Columbia group calling itself the Vancouver Gay Liberation Front emerged in 1971, mostly out of meetings from a local commune, called Pink Cheeks. The group gained support from The Georgia Straight, a left-leaning newspaper, and opened a drop-in centre and published a newsletter.[38] The group struggled to maintain a core group of members, and competition from other local groups, such as the Canadian Gay Activists Alliance (CGAA) and the Gay Alliance Toward Equality (GATE), soon led to its demise.[39]

See also[]

- Gay Activists Alliance

- Gay Left, UK gay collective and journal

- Hall-Carpenter archives

- List of LGBT rights organizations

- Notable members of the GLF in London: Sam Green, Angela Mason, Mary Susan McIntosh, Bob Mellors, Peter Tatchell, Alan Wakeman

- Notable members of the GLF in the USA: Arthur Bell, Arthur Evans, Tom Brougham, N. A. Diaman, Jim Fouratt, Harry Hay, Brenda Howard, Karla Jay, Marsha P. Johnson, Charles Pitts, Sylvia Rivera, Martha Shelley, Jim Toy, Dan C. Tsang, Allen Young

- OutRage!

- Socialism and LGBT rights

- Stonewall riots

- Stonewall UK

Footnotes[]

- ^ "Gay Liberation Front at Alternate U. - NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project". Nyclgbtsites.org.

- ^ National Park Service (2008). "Workforce Diversity: The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". US Department of Interior. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ^ "Obama inaugural speech references Stonewall gay-rights riots". North Jersey Media Group Inc. January 21, 2013. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shepard, Benjamin Heim and Ronald Hayduk (2002) From ACT UP to the WTO: Urban Protest and Community Building in the Era of Globalization. Verso. pp.156-160 ISBN 978-1859-8435-67

- ^ Bernadicou, August. "Martha Shelley". August Nation. The LGBTQ History Project. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Abelove, Henry (June 26, 2015). "How Stonewall Obscures the Real History of Gay Liberation". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ^ Teal, Donn (1971). The Gay Militants: How Gay Liberation Began in America, 1969-1971. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 52–58. ISBN 0312112793.

- ^ Gould, Robert E. (24 February 1974). "What We Don't Know About Homosexuality". New York Times Magazine. ISBN 9780231084376. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ Laurence, Leo E. (October 31 – November 6, 1969). "Gays Penetrate Examiner". Berkeley Tribe. 1 (17). p. 4. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Alwood, Edward (1996). Straight News: Gays, Lesbians, and the News Media. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08436-6. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ Bell, Arthur (28 March 1974). "Has The Gay Movement Gone Establishment?". The Village Voice. ISBN 9780231084376. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Van Buskirk, Jim (2004). "Gay Media Comes of Age". Bay Area Reporter. Archived from the original on July 5, 2015. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ Stryker, Susan; Buskirk, Jim Van (November 15–30, 1969). "Friday of the Purple Hand". San Francisco Free Press. ISBN 9780811811873. Retrieved January 1, 2008. (courtesy: the Gay Lesbian Historical Society.

- ^ Martin, Del (December 1969). "The Police Beat: Crime in the Streets" (PDF). Vector (San Francisco). 5 (12): 9. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b ""Gay Power" Politics". GLBTQ, Inc. 30 March 2006. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ "glbtq >> social sciences >> San Francisco". Archived from the original on 2015-07-05. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- ^ Montanarelli, Lisa; Harrison, =Ann (2005). Strange But True San Francisco: Tales of the City by the Bay. Globe Pequot. ISBN 0-7627-3681-X. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ Alwood, Edward (24 April 1974). "Newspaper Series Surprises Activists". The Advocate. ISBN 9780231084376. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ Nash, Jay Robert (1993). World Encyclopedia of Organized Crime. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80535-9.

- ^ "MorEl Eskişehir LGBTT Oluşumu". Moreleskisehir.blogspot.com. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ Bernadicou, August. "Martha Shelley". August Nation. The LGBTQ History Project. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Feinberg, Leslie (September 24, 2006). "Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries". Workers World Party. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

Stonewall combatants Sylvia Rivera and Marsha "Pay It No Mind" Johnson ... Both were self-identified drag queens.

- ^ "Gay Group Loses Campground Use", Lodi News Sentinel, 26 June 1970.

- ^ "Gay Liberation Front: Manifesto. London". 1978 [1971].

- ^ Stuart Weather. "A brief history of the Gay Liberation Front, 1970-73". libcom.org. Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lucas 1998, pp. 2–3

- ^ Brittain, Victoria (28 August 1971). "An Alternative to Sexual Shame: Impact of the new militancy among homosexual groups". The Times. p. 12.

- ^ "Gay Liberation Front (GLF)". Database of Archives of Non-Government Organisations. January 4, 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-20.

- ^ Power, Lisa (1995). No Bath But Plenty Of Bubbles: An Oral History Of The Gay Liberation Front 1970-7. Cassell.

- ^ Gingell, Basil (10 September 1971). "Uproar at Central Hall as demonstrators threaten to halt Festival of Light". The Times. p. 14.

- ^ "Gay Birmingham Remembered - The Gay Birmingham History Project". . Retrieved 3 October 2012.

Birmingham hosted the Gay Liberation Front annual conference in 1972, at the chaplaincy at Birmingham University Guild of Students.

- ^ Peace News John Birdsall page 2 (13 January 1978)

- ^ Gay News (1978) Demonstrators protest at ad ban on help-line edition number 135

- ^ "Calmview: Collection Browser". archives.lse.ac.uk. LSE Library Services. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Willett, p. 86

- ^ Tatchell, Peter. "Peter Tatchell: The Art of Activism". petertatchell.net. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Robinson, Lucy (2007). Gay men and the left in post-war Britain: How the personal got political. Manchester University Press. pp. 174–176. ISBN 9781847792334. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Warner, Tom (2002). Never going back : a history of queer activism in Canada. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780802084606.

- ^ Rothon, Robert (October 23, 2008). "Vancouver's Gay Liberation Front". Daily Xtra.

References[]

- Canfield, William J. "We Raise our Voices". Gay & Lesbian Pride & Politics.

- Diaman, N. A. (1995). "Gay Liberation Front". Archived from the original on 2007-06-11.

- Kissack, Terence (1995). Freaking Fag Revolutionaries: New York's Gay Liberation Front. Radical History Review 62.

- Lucas, Ian (1998), OutRage!: an oral history, Cassell, ISBN 978-0-304-33358-5

- Power, Lisa (1995). No Bath But Plenty Of Bubbles: An Oral History Of The Gay Liberation Front 1970-7. Cassell. p. 340 pages. ISBN 0-304-33205-4.

- Walter, Aubrey (1980). Come together : the years of gay liberation (1970-73). Gay Men's Press. p. 218 pages. ISBN 0-907040-04-7.

- Wright, Lionel (July 1999). "The Stonewall Riots – 1969". Socialism Today #40.

- Kafka, Tina (2006). Gay Rights. Thomson Gale Farmington Hills, MI.

External links[]

- Gay Liberation Front - first newspaper, photos

- Gay Liberation Front - DC, 1970-1972

- Leicester Gay Liberation Front

- Photographs of New York GLF meetings, actions and members by Diana Davies at the New York Public Library Digital Collections

- Resources on the Politics of Homosexuality in the UK from a socialist perspective

- Then and now

- Gay Liberation Front members

- LGBT political advocacy groups in the United States

- History of LGBT civil rights in the United States

- LGBT history in New York City

- LGBT history in the United Kingdom

- Far-left politics in the United States

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- LGBT political advocacy groups in Canada

- LGBT political advocacy groups in the United Kingdom

- Organizations established in 1969

- 1969 establishments in New York (state)