George Dennick Wick

Colonel George D. Wick | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 19, 1854 |

| Died | April 15, 1912 (aged 58) Lost at sea (Titanic) |

| Occupation | Industrialist |

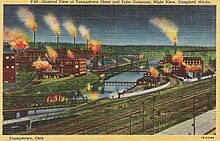

| Title | Founding President, Youngstown Sheet and Tube |

| Signature | |

| |

Colonel George Dennick Wick (February 19, 1854 – April 15, 1912) was an American industrialist who served as founding president of the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company, one of the nation's largest regional steel-manufacturing firms.[1] He perished in the Atlantic during the sinking of RMS Titanic.[2]

Early life and career[]

Wick was born in Youngstown, Ohio, United States, where his family was established in the sectors of real estate and banking.[3] Nineteenth-century Youngstown was a center of coal mining and iron production; and Wick, a resourceful entrepreneur, launched several ventures with business partner James A. Campbell,[3] who later served as director of the American Iron and Steel Institute.[4]

In 1895, Wick and Campbell organized the Mahoning Valley Iron Company, with Wick as president. Five years later, the two men resigned from the firm when it was taken over by the Republic Iron and Steel Company,[5] and their next project would come in response to major changes that occurred in the community's industrial sector. Youngstown's industrial leaders began to convert from iron to steel manufacturing at the turn of the century, a period that also saw a wave of consolidations that placed much of the community's industry in the hands of national corporations.[6] To the rising concern of many area industrialists, U.S. Steel, shortly after its establishment in 1901, absorbed Youngstown's premier steel producer, the National Steel Company.[6]

During the previous year, however, Wick and Campbell pooled resources with other local investors who wanted to maintain significant levels of local ownership within the city's manufacturing sector.[6] The group established the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company with $600,000 in capital[3] and eventually turned it into one of the nation's most important steel producers.[7] Wick, who emerged as the steel company's first president in 1900, appointed Campbell as secretary. Two years later, Campbell rose to the position of vice president; and in 1904, he began his long tenure as president of Youngstown Sheet and Tube.[8] Wick, meanwhile, was forced to take an extended leave of absence because of health problems, though he returned to the company a few years before his death.[5]

Death on Titanic[]

Wick embarked on a European tour in 1912, in an effort to restore his health. He was joined by his wife, Mary Hitchcock Wick; his daughter, Mary Natalie Wick; a cousin, Caroline Bonnell; and Caroline's English aunt, Elizabeth Bonnell.[3] On April 10, 1912, the group boarded RMS Titanic, at Southampton, England. The new luxury liner was bound for New York, with 2,224 passengers and crew aboard.[9]

At 11:40 p.m., on April 14, one of the ship's lookouts rang a bell to signal that an object lay directly in the ship's path. The vessel turned to avoid a collision, but the submerged portion of an iceberg gouged its bulkhead and bilges.[9] In the confusion that followed, Wick was last seen on the deck of the sinking ocean liner, waving to relatives as they were helped into lifeboats.[10] Caroline Bonnell, who boarded one of the first lifeboats dispatched from the ship, told reporters what happened later: "There was a big wave. The sea was calm, otherwise, and I asked a sailor what it was. He said, 'the Titanic has sunk!'"[11] Wick's body was never recovered.[12]

Following official confirmation that George D. Wick was lost at sea, Youngstown's municipal government declared that all local factories, businesses, and schools should observe five minutes of silence at 11 a.m. on April 24, 1912, to honor the industrialist's memory.[12] Meanwhile, the Wick family's pew at the city's First Presbyterian Church was roped off, and flags throughout the community were flown at half mast.[3] A memorial monument was later erected for Wick at Youngstown's Oak Hill Cemetery.[12]

Legacy[]

The steel company Wick helped to organize flourished for many decades. In 1923, Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company purchased plants in the Chicago area whose output represented about one-third of the company's total national production capacity. Following a slump in the 1960s, however, owners attempted to revamp the company's Youngstown operations with profits generated from newer plants in Illinois and Indiana. This strategy was abandoned after Youngstown Sheet and Tube was taken over by New Orleans-based Lykes Industries, which closed Youngstown's steel plants in the 1970s.[13]

Notes[]

- ^ Jenkins, Janie S (April 15, 1977). "Col. Wick Lost Life in Sinking—Tragedy of the Titanic Left Its Mark on City". Youngstown Vindicator. p. 8.

- ^ Feagler, Linda (April 2005). "Fate-filled Voyage". Ohio Magazine. p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e Klein, Miriam R (January 1998). "Ill-Fated Voyage Of Titanic Claimed Area Industrialist". The Metro Monthly. p. 6.

- ^ Fuechtmann (1989), p. 12.

- ^ a b OhioPix Accessed 2007-03-27[dead link]

- ^ a b c Blue et al. (1995), p. 94.

- ^ Fuechtmann (1989), p. 16.

- ^ "Death Ends J. A. Campbell's Career; Sudden Attack Is Fatal to Sheet & Tube's Builder". The Youngstown Vindicator. September 21, 1933. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Titanic Sank 20 Years Ago: Worst Sea Disaster in History Recalled—Four Youngstowners on Board". The Youngstown Daily Vindicator. April 14, 1932.

- ^ "Miss Bonnell's Graphic Story Of The Rescue of Survivors". The Youngstown Daily Vindicator. April 19, 1912.

- ^ "Tells of Women Pulling Oars; Youngstown Woman Relates Story of Escape from Sinking Titanic". The Cleveland Plain Dealer. April 19, 1912. p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Catastrophe at Sea Stunned City 25 Years Ago Tonight". The Youngstown Daily Vindicator. April 14, 1937.

- ^ Fuechtmann (1989), pp. 41–43.

References[]

- Blue, Frederick J.; et al. (1995). Mahoning Memories: A History of Youngstown and Mahoning County. Virginia Beach, VA: The Donning Company, p. 94. ISBN 0-89865-944-2.

- Fuechtmann, Thomas G. (1989). Steeples and Stacks: Religion and Steel Crisis in Youngstown. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- 1854 births

- 1912 deaths

- American manufacturing businesspeople

- Deaths on the RMS Titanic

- Businesspeople from Youngstown, Ohio

- American steel industry businesspeople

- 19th-century American businesspeople