J. Bruce Ismay

J. Bruce Ismay | |

|---|---|

Ismay in 1912 | |

| Born | Joseph Bruce Ismay 12 December 1862 Crosby, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 17 October 1937 (aged 74) Mayfair, London, England |

| Occupation | Chairman and Managing director of White Star Line |

| Title | Ship-owner |

| Spouse(s) | Julia Florence Schieffelin

(m. 1888) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

Joseph Bruce Ismay (/ɪzˈmeɪ/; 12 December 1862[1]– 17 October 1937) was an English businessman who served as chairman and managing director of the White Star Line.[2] In 1912, he came to international attention as the highest-ranking White Star official to survive the sinking of the company's new flagship RMS Titanic, for which he was subject to severe criticism.

Early life[]

Ismay was born in Crosby, Lancashire. He was the son of Thomas Henry Ismay (7 January 1837 – 23 November 1899) and Margaret Bruce (13 April 1837 – 9 April 1907), daughter of ship-owner Luke Bruce.[1] Thomas Ismay was the senior partner in Ismay, Imrie and Company and the founder of the White Star Line.[a][3] The younger Ismay was educated at Elstree School and Harrow,[4] then tutored in France for a year. He was apprenticed at his father's office for 4 years, after which he toured the world. He then went to New York City as the company representative, eventually rising to the rank of agent.[5] Bruce was one of the founding team of Liverpool Ramblers football club in 1882.[6]

On 4 December 1888, Ismay married Julia Florence Schieffelin (5 March 1867 – 31 December 1963), daughter of George Richard Schieffelin and Julia Matilda Delaplaine of New York, with whom he had five children:[7]

- Margaret Bruce Ismay (29 December 1889 – 15 May 1967), who married George Ronald Hamilton Cheape (1881–1957) in 1912

- Henry Bruce Ismay (3 April 1891 – 1 October 1891)

- Thomas Bruce Ismay (18 February 1894 – 27 April 1954), who married Jane Margaret Seymour

- Evelyn Constance Ismay (17 July 1897 – 9 August 1940), who married Basil Sanderson (1894–1971) in 1927

- George Bruce Ismay (6 June 1902 – 30 April 1943), who married Florence Victoria Edrington in 1926.[8]

In 1891, Ismay returned with his family to the United Kingdom and became a partner in his father's firm, Ismay, Imrie and Company. In 1899, Thomas Ismay died, and Bruce Ismay became head of the family business. Ismay had a head for business, and the White Star Line flourished under his leadership. In addition to running his ship business, Ismay also served as a director of several other companies. In 1901, he was approached by Americans who wished to build an international shipping conglomerate, to which he agreed to sell his firm to the International Mercantile Marine Company.[3]

Chairman of the White Star Line[]

After the death of his father on 23 November 1899,[9][10] Bruce Ismay succeeded him as the chairman of the White Star Line. He decided to build four ocean liners to surpass the RMS Oceanic built by his father: the ships were dubbed the Big Four: RMS Celtic, RMS Cedric, RMS Baltic, and RMS Adriatic. These vessels were designed more for size and luxury than for speed.[11]

In 1902, Ismay oversaw the sale of the White Star Line to J.P. Morgan & Co., which was organising the formation of International Mercantile Marine Company, an Atlantic shipping combine which absorbed several major American and British lines. IMM was a holding company that controlled subsidiary operating corporations. Morgan hoped to dominate transatlantic shipping through interlocking directorates and contractual arrangements with the railroads, but that proved impossible because of the unscheduled nature of sea transport, American antitrust legislation, and an agreement with the British government.[12] White Star Line became one of the IMM operating companies and, in February 1904, Ismay became president of the IMM, with the support of Morgan.[13]

RMS Titanic[]

In 1907, Ismay met Lord Pirrie of the Harland & Wolff shipyard to discuss White Star's answer to the RMS Lusitania and the RMS Mauretania,[b] the recently unveiled marvels of their chief competitor, Cunard Line. Ismay's new type of ship would not be as fast as their competitors, but it would have huge steerage capacity and luxury unparalleled in the history of ocean-going steamships. The latter feature was largely meant to attract the wealthy and the prosperous middle class. Three ships of the Olympic class were planned and built. They were in order RMS Olympic, RMS Titanic and RMS (later HMHS) Britannic. In a highly controversial move, during construction of the first two Olympic-class liners, Ismay authorised the projected number of lifeboats reduced from 48 to 16, the latter being the minimum allowed by the Board of Trade, based on the RMS Olympic's tonnage.[15][16]

Ismay occasionally accompanied his ships on their maiden voyages, and this was the case with the Titanic.[3] During the voyage, Ismay talked with either (or possibly both) chief engineer Joseph Bell or Captain Edward J. Smith about a possible test of speed if time permitted.[17] After the ship collided with an iceberg 400 miles south of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland on the night of 14 April 1912, it became clear that it would sink long before any rescue ships could arrive. Ismay stepped aboard Collapsible C, which was launched less than 20 minutes before the ship went down.[18] He later testified that as the ship was in her final moments, he turned away, unable to watch. Collapsible C was picked up by the Carpathia about 3–4 hours later.

After being picked up by the Carpathia, Ismay was led to the cabin belonging to the ship's doctor, Frank Mcgee. He gave Captain Rostron a message to send to White Star's New York office:

"Deeply regret advise you Titanic sank this morning fifteenth after collision iceberg, resulting serious loss life further particulars later". Bruce Ismay.

Ismay did not leave Dr. Mcgee's cabin for the entire journey, ate nothing solid, and was kept under the influence of opiates.[19][20] Another survivor, 17-year-old Jack Thayer, visited Ismay to try to console him, despite having just lost his father in the sinking.

[Ismay] was staring straight ahead, shaking like a leaf. Even when I spoke to him, he paid absolutely no attention. I have never seen a man so completely wrecked.[21]

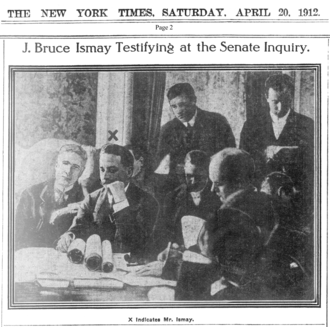

When he arrived in New York, Ismay was hosted by Philip Franklin, vice president of the company. He also received a summons to appear before a Senate committee headed by Republican Senator William Alden Smith. Ismay later testified at the Titanic disaster inquiry hearings held by both the U.S. Senate (chaired by Senator William Alden Smith) the following day, and the British Board of Trade (chaired by Lord Mersey) a few weeks later.

Criticism[]

After the disaster, Ismay was savaged by both the American and the British press for deserting the ship while women and children were still on board. Some papers called him the "Coward of the Titanic" or "J. Brute Ismay", and suggested that the White Star flag be changed to a yellow liver. Some ran negative cartoons depicting him deserting the ship. The writer Ben Hecht, then a young newspaperman in Chicago, wrote a scathing poem contrasting the actions of Captain Smith and Ismay. The final verse reads: "To hold your place in the ghastly face / of death on the sea at night / is a seaman's job, but to flee with the mob / is an owner's noble right."[22]

Some maintain Ismay followed the "women and children first" principle, having assisted many women and children himself. Ismay's actions were defended in the official British inquiry, which found "Mr. Ismay, after rendering assistance to many passengers, found "C" collapsible, the last boat on the starboard side, actually being lowered. No other people were there at the time. There was room for him and he jumped in. Had he not jumped in he would merely have added one more life—namely, his own—to the number of those lost."[23]

Ismay had boarded Collapsible C with first-class passenger William Carter; both said they did so after there were no more women and children near that particular lifeboat.[24] Carter's own behaviour and reliability, however, were criticised by Mrs. Lucile Carter, who sued him for divorce in 1914; she testified Carter had left her and their children to fend for themselves after the collision and accused him of "cruel and barbarous treatment and indignities to the person".[25] London society ostracised Ismay and labelled him a coward. On 30 June 1913, Ismay resigned as president of International Mercantile Marine and chairman of the White Star Line, to be succeeded by Harold Sanderson.[26]

Ismay announced during the United States Inquiry that all the vessels of the International Mercantile Marine Company would be equipped with lifeboats in sufficient numbers for all passengers.[27] Following the inquiry, Ismay and the surviving officers of the ship returned to England aboard RMS Adriatic.

Titanic controversy[]

During the congressional investigations, some passengers testified that during the voyage they heard Ismay pressuring Captain Smith to increase the speed of the Titanic in order to arrive in New York ahead of schedule and generate some free press about the new liner. The book The White Star Line: An Illustrated History (2000) by Paul Louden-Brown states that this was unlikely, and that Ismay's record does not support the notion that he had any motive to do so.[28]

Writing on the BBC News magazine website, Rosie Waites reports that Ismay was widely vilified in the United States after the sinking of the Titanic, due to the hostility shown in the yellow press controlled by William Randolph Hearst, who had fallen out with Ismay. Waites writes "Ismay was almost universally condemned in America, where the Hearst syndicated press ran a vitriolic campaign against him, labelling him 'J. Brute Ismay'. It published lists of all those who died but in the column of those saved it had just one name – Ismay's."[29]

Following from the Hearst press depiction of Ismay, Waites writes that every subsequent film about the Titanic has depicted Ismay as a villain, starting with the 1943 Nazi propaganda film Titanic; the 1996 miniseries Titanic; James Cameron's Titanic; and Julian Fellowes' TV miniseries Titanic, where he is portrayed as a racist who orders a group of non-British crew members locked below to drown.[29] Louden-Brown, consultant to the Cameron film, has stated that he thought the antagonistic characterisation of Ismay was unfair and he tried to challenge this. Louden-Brown said "Apart from being told, under no circumstances are we prepared to adjust the script, one thing they also said is 'this is what the public expect to see'."[29] The 1958 film A Night to Remember did not blame Ismay for the disaster, but also presented him in an unfavourable and cowardly light, while a Titanic-themed episode of the science fiction television series Voyagers! portrayed Ismay dressing as a woman in order to sneak into a lifeboat.

Lord Mersey, who led the 1912 British inquiry into the sinking of the Titanic, concluded that Ismay had helped many other passengers before finding a place for himself on the last lifeboat to leave the starboard side.[29]

Later life[]

Though cleared of blame by the official British inquiry, Ismay never recovered from the Titanic disaster. Already emotionally repressed and insecure before his voyage on Titanic,[30] the tragedy sent him into a state of deep depression from which he never truly emerged.[31] He kept a low profile afterwards. He lived part of the year in a large cottage, Costelloe Lodge, near Casla in Connemara, County Galway, Ireland. Paul Louden-Brown, in his history of the White Star Line, writes that Ismay continued to be active in business, and that much of his work was for The Liverpool & London Steamship Protection & Indemnity Association Limited, an insurance company founded by his father. According to Louden-Brown:

Hundreds of thousands of pounds were paid out in insurance claims to the relatives of the Titanic's victims; the misery created by the disaster and its aftermath dealt with by Ismay and his directors with great fortitude, this, despite the fact that he could easily have shirked his responsibilities and resigned from the board. He stuck with the difficult task and during his twenty-five-year chairmanship hardly a page of the company's minutes does not contain some mention of the Titanic disaster.[28]

Ismay maintained an interest in maritime affairs. He inaugurated a cadet ship called Mersey used to train officers for Britain's Merchant Navy, donated £11,000 to start a fund for lost seamen, and in 1919 gave £25,000 (approximately equivalent to £1,173,000 in 2019)[32] to set up a fund to recognise the contribution of merchant mariners in the First World War.[33]

After the tragedy, Ismay's wife Florence ensured the subject of Titanic was never again discussed within the family. His granddaughter, historian and author Pauline Matarasso, likened her grandfather to a "corpse" in his later years:

Having had the misfortune (one might say the misjudgement) to survive – a fact he recognised despairingly within hours – he withdrew into a silence in which his wife made herself complicit – imposing it on the family circle and thus ensuring that the subject of the Titanic was as effectively frozen as the bodies recovered from the sea.[34]

In his personal life, Ismay became a man of solitary habits, spending his summers at his Connemara cottage and indulging in a love of trout and salmon fishing. When in London, he would attend concerts by himself at St George's Hall or visit a cinema, at other times wandering through the London parks and engaging transients in conversation.[35] A family friend observed the spectre of Titanic was never far from Ismay's thoughts, saying that he continually "tormented himself with useless speculation as to how the disaster could possibly have been avoided."[36] At a Christmastime family gathering in 1936, less than a year before Ismay's death, one of his grandsons by his daughter Evelyn, who had learned Ismay had been involved in maritime shipping, enquired if his grandfather had ever been shipwrecked. Ismay finally broke his quarter-century silence on the tragedy that had blighted his life, replying, "Yes, I was once in a ship which was believed to be unsinkable."[36]

Death[]

Ismay's health declined in the 1930s, following a diagnosis of diabetes,[24] which worsened in early 1936, when the illness resulted in the amputation of his right leg below the knee. He was subsequently largely confined to a wheelchair.[37] On the morning of 14 October 1937, he collapsed in his bedroom at his residence in Mayfair, London, after suffering a massive stroke, which left him unconscious, blind and mute.[37] Three days later, on 17 October, J. Bruce Ismay died at the age of 74.[2]

Ismay's funeral was held at St Paul's, Knightsbridge, on 21 October 1937,[38] and he is buried in Putney Vale Cemetery, London.[39] He left a very considerable personal estate, which excluding property was valued at £693,305 (approximately equivalent to £41,520,000 in 2019).[32] After his death, his wife Florence renounced her British subject status in order to restore her American citizenship on 14 November 1949. Julia Florence Ismay, née Schieffelin, died 31 December 1963, aged 96, in Kensington, London.

Portrayals[]

- Ernst Fritz Fürbringer (1943) (Titanic)

- Lowell Gilmore (1955) (You Are There: The Sinking of the Titanic (TV episode, 22 May 1955)

- Frank Lawton (1958) (A Night to Remember)

- Ian Holm (1979) (S.O.S. Titanic) (TV film)

- Sam Chew, Jr. (1982) (Voyagers!) (Voyagers of the Titanic)

- Roger Rees (1996) (Titanic) (TV miniseries/2 parts)

- Jonathan Hyde (1997) (Titanic) (Film)

- David Garrison (1997) (Titanic) (Broadway musical)

- David Haines (2006) (Titanic) (Broadway musical – Canadian premiere)

- Eric Braeden (1999) (The Titanic Chronicles) (TV documentary)

- Ken Marschall (2003) (Ghosts of the Abyss) (Documentary)

- Christopher Wright (2005) (Titanic: Birth of a Legend) (TV documentary)

- Mark Tandy (2008) (The Unsinkable Titanic) (TV documentary)

- Christopher Villiers (2011) (The Curiosity: What Sank Titanic?) (TV series)

- James Wilby (2012) (Titanic) (TV series/4 episodes)

- Gray O'Brien (2012) (Titanic: Blood and Steel) (TV series/12 episodes)

- Julien Ball (2012) (Iceberg – Right Ahead!) (London stage play)

- Michael Maloney (2012) (Sherlock Holmes: The Adventure of the Perfidious Mariner) (audio play)

- Derek Mahon ("After the Titanic") (poem)

See also[]

- Passengers of the RMS Titanic

Notes[]

- ^ Oceanic Steam Navigation Company was generally known as White Star Line, which was the name of the company purchased by Thomas Ismay.

- ^ The duo themselves were designed to compete with the SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse and SS Deutschland owned respectively by the Norddeutscher Lloyd and the Hamburg America Line, the two German top shipping companies.

- ^ Gravestone inscriptions:

They that go down to the sea

in ships and occupy their

business in great waters

these men see the works of the

Lord and His wonders in the deep.

To the glory of God and in memory of

Bruce Ismay died October 17th 1937

his wife Julia Florence Ismay

died December 31st 1963

References[]

Citations

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mr Joseph Bruce Ismay". Encyclopedia Titanica. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "J. Bruce Ismay, 74, Titanic Survivor. Ex-Head of White Star Line Who Retired After Sea Tragedy Dies in London". The New York Times. 19 October 1937. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

Joseph Bruce Ismay, former chairman of the White Star Line and a survivor of the Titanic disaster in 1912, died here last night. He was 74 years old.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Histoire de la White Star Line". Le Site du Titanic (in French). Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ^ Wilson, Frances (2011). How to Survive the Titanic or the Sinking of J. Bruce Ismay. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-1-4088-2111-4.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 144.

- ^ "An Introduction". liverpoolramblersafc.com. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Married in early December". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2009 – via Encyclopedia Titanica.

- ^ Reading Room Manchester (30 April 1943). "Commonwealth War Graves Commission". Cwgc.org. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ "Thomas Henry Ismay: The man and his background". The Ismay Family. 2004. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ^ "Thomas Henry Ismay dead". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2009 – via Encyclopedia Titanica.

- ^ Chirnside 2004, p. 11.

- ^ John J. Clark, and Margaret T. Clark, "The International Mercantile Marine Company: A Financial Analysis," American Neptune 1997 57(2): 137–154.

- ^ "Griscom is no longer head of the Ship Combine". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2009 – via Encyclopedia Titanica.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ismay's Lifeboat Orders, Made No Distinction Between Men and Women, Says, Behr (and) In the Boat With Ismay, W.E. Carter Says They Got in When No Women Were There". The New York Times. 20 April 1912. p. 2.

- ^ 3 November 2008 Channel 4 documentary The Unsinkable Titanic.

- ^ "Les canots de sauvetage". Le Site du Titanic (in French). Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Piouffre 2009, pp. 111–112.

- ^ "Composition du Radeau Pliable C". Le Site du Titanic (in French). Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ^ Piouffre 2009, p. 207.

- ^ Piouffre 2009, p. 209.

- ^ Wilson, Frances (15 March 2012). How to Survive the Titanic or the Sinking of J. Bruce Ismay. ISBN 9781408828151.

- ^ Lord, Walter (1986). The Night Lives On. New York: William Morrow and Company. pp. 211–12. ISBN 978-0-688-04939-3.

- ^ "Shipping casualties (loss of the steamship Titanic). Report of a formal investigation into the circumstances attending the foundering on 15th April, 1912, of the British steamship Titanic, of Liverpool, after striking ice in or near latitude 410 46' N., Longitude 500 14' W., North Atlantic Ocean, whereby loss of life ensued." Cd. 6532, p. 40.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stewart, Linda (5 April 2011). "Did Joseph Bruce Ismay dress as a woman to flee Titanic?". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Lord, Walter (1986). The Night Lives On. New York: William Morrow and Company. pp. 216–217. ISBN 978-0-688-04939-3.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew 2012, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Piouffre 2009, p. 257.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Louden-Brown, Paul (10 January 2001). "Ismay and the Titanic". Titanic Historical Society. Archived from the original on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Waites, Rosie (5 April 2012). "Five Titanic myths spread by films". BBC News. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew 2012, pp. 198–202.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew 2012, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b United Kingdom Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth "consistent series" supplied in Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2018). "What Was the U.K. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "Titanic 15 April 1912". titanictown.plus.com. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew 2012, p. 7.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew 2012, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wilson, Andrew 2012, p. 216.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wilson, Andrew 2012, p. 218.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew 2012, p. 219.

- ^ Kerrigan, Michael (1998). Who Lies Where – A guide to famous graves. London: Fourth Estate Limited. p. 285. ISBN 978-1-85702-258-2.

Sources

- Chirnside, Mark (2004). The Olympic-Class Ships. Stroud, England: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2868-0.

- Piouffre, Gérard (2009). Le Titanic ne répond plus (in French). Larousse. ISBN 978-2-263-02799-4.

- Wilson, Andrew (2012). Shadow of the Titanic: the extraordinary stories of those who survived. Atria Books. ISBN 978-1451671568.

Further reading[]

- Gardiner, Robin (2002). History of the White Star Line. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-2809-8.

- Oldham, Wilton J. (1961). "The Ismay Line: The White Star Line, and the Ismay family story". The Journal of Commerce. Liverpool.

- Wilson, Frances (2012). How to Survive the Titanic, or the Sinking of J. Bruce Ismay. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0062094551.

External links[]

- 1862 births

- 1937 deaths

- People educated at Elstree School

- People educated at Harrow School

- RMS Titanic's crew and passengers

- British racehorse owners and breeders

- People from Crosby, Merseyside

- Burials at Putney Vale Cemetery

- Businesspeople from Liverpool

- British businesspeople in shipping

- Deaths from cerebrovascular disease

- Liverpool Ramblers F.C. players

- Directors of the London and North Western Railway

- White Star Line

- RMS Titanic survivors

- English footballers