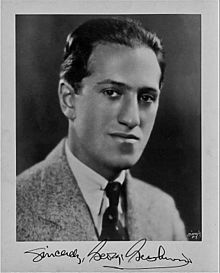

George Gershwin

George Gershwin | |

|---|---|

Gershwin in 1937 by Carl Van Vechten | |

| Born | September 26, 1898 Brooklyn, New York City, U.S. |

| Died | July 11, 1937 (aged 38) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Westchester Hills Cemetery |

| Occupation | Composer, pianist |

| Years active | 1916–1937 |

| Height | 5 ft 11 in (180 cm) |

| Relatives |

|

George Gershwin (/ˈɡɜːrʃ.wɪn/; born Jacob Gershwine;[1][2] September 26, 1898 – July 11, 1937) was an American composer and pianist,[3][4] whose compositions spanned both popular and classical genres. Among his best-known works are the orchestral compositions Rhapsody in Blue (1924) and An American in Paris (1928), the songs "Swanee" (1919) and "Fascinating Rhythm" (1924), the jazz standards "Embraceable You" (1928) and "I Got Rhythm" (1930), and the opera Porgy and Bess (1935), which included the hit "Summertime".

Gershwin studied piano under Charles Hambitzer and composition with Rubin Goldmark, Henry Cowell, and Joseph Brody. He began his career as a song plugger but soon started composing Broadway theater works with his brother Ira Gershwin and with Buddy DeSylva. He moved to Paris intending to study with Nadia Boulanger, but she refused him, afraid that rigorous classical study would ruin his jazz-influenced style. He subsequently composed An American in Paris, returned to New York City and wrote Porgy and Bess with Ira and DuBose Heyward. Initially a commercial failure, it came to be considered one of the most important American operas of the twentieth century and an American cultural classic.

Gershwin moved to Hollywood and composed numerous film scores. He died in 1937 of a malignant brain tumor.[5] His compositions have been adapted for use in film and television, with several becoming jazz standards recorded and covered in many variations.

Biography[]

Ancestors[]

Gershwin was of Ukrainian-Jewish ancestry.[6] His grandfather, Jakov Gershowitz, was born in Odessa and had served for 25 years as a mechanic for the Imperial Russian Army to earn the right of free travel and residence as a Jew, finally retiring near Saint Petersburg. His teenage son Moishe worked as a leather cutter for women's shoes. Moishe Gershowitz met and fell in love with Roza Bruskina, the teenage daughter of a furrier in Vilnius. She and her family moved to New York because of increasing anti-Jewish sentiment in Russia, changing her first name to Rose. Moishe, faced with compulsory military service if he remained in Russia, moved to America as soon as he could afford to. Once in New York, he changed his first name to Morris. Gershowitz lived with a maternal uncle in Brooklyn, working as a foreman in a women's shoe factory. He married Rose on July 21, 1895, and Gershowitz soon Americanized his name to Gershwine.[7][8][9] Their first child, Ira Gershwin, was born on December 6, 1896, after which the family moved into a second-floor apartment at 242 Snediker Avenue in the East New York neighborhood of Brooklyn.

Early life[]

On September 26, 1898, George was born in the Snediker Avenue apartment. His birth certificate identifies him as Jacob Gershwine, with the surname pronounced 'Gersh-vin' in the Russian and Yiddish immigrant community.[10][11] He was named after his grandfather, and, contrary to the American practice, had no middle name. He soon became known as George,[12] and changed the spelling of his surname to 'Gershwin' around the time he became a professional musician; other family members followed suit.[13] After Ira and George, another boy, Arthur Gershwin (1900–1981), and a girl, Frances Gershwin (1906–1999), were born into the family.

The family lived in many different residences, as their father changed dwellings with each new enterprise in which he became involved. They grew up mostly in the Yiddish Theater District. George and Ira frequented the local Yiddish theaters, with George occasionally appearing onstage as an extra.[14][15][16]

George lived a boyhood not unusual in New York tenements, which included running around with his friends, roller-skating and misbehaving in the streets. Until 1908, he cared nothing about music. Then, as a ten-year-old, he was intrigued upon hearing his friend Maxie Rosenzweig's violin recital.[17] The sound, and the way his friend played, captivated him. At about the same time, George's parents had bought a piano for his older brother Ira. To his parents' surprise, though, and to Ira's relief, it was George who spent more time playing it as he continued to enjoy it.[18]

Although his younger sister Frances was the first in the family to make a living through her musical talents, she married young and devoted herself to being a mother and housewife, thus precluding spending any serious time on musical endeavors. Having given up her performing career, she settled upon painting as a creative outlet, which had also been a hobby George briefly pursued. Arthur Gershwin followed in the paths of George and Ira, also becoming a composer of songs, musicals, and short piano works.

With a degree of frustration, George tried various piano teachers for about two years (circa 1911) before finally being introduced to Charles Hambitzer by Jack Miller (circa 1913), the pianist in the Beethoven Symphony Orchestra. Until his death in 1918, Hambitzer remained Gershwin's musical mentor, taught him conventional piano technique, introduced him to music of the European classical tradition, and encouraged him to attend orchestral concerts.[19]

Tin Pan Alley and Broadway, 1913–1923[]

In 1913, Gershwin left school at the age of 15 to work as a "song plugger" on New York City's Tin Pan Alley. He earned $15 a week for Jerome H. Remick and Company, a Detroit-based publishing firm with a branch office in New York.

His first published song was "When You Want 'Em, You Can't Get 'Em, When You've Got 'Em, You Don't Want 'Em" in 1916. It earned the 17-year-old 50 cents.[20]

In 1916, Gershwin started working for Aeolian Company and Standard Music Rolls in New York, recording and arranging. He produced dozens, if not hundreds, of rolls under his own and assumed names (pseudonyms attributed to Gershwin include Fred Murtha and Bert Wynn). He also recorded rolls of his own compositions for the Duo-Art and Welte-Mignon reproducing pianos. As well as recording piano rolls, Gershwin made a brief foray into vaudeville, accompanying both Nora Bayes and Louise Dresser on the piano.[21] His 1917 novelty ragtime, "Rialto Ripples", was a commercial success.[20]

In 1919 he scored his first big national hit with his song "Swanee," with words by Irving Caesar. Al Jolson, a Broadway star and former minstrel singer, heard Gershwin perform "Swanee" at a party and decided to sing it in one of his shows.[20]

In the late 1910s, Gershwin met songwriter and music director William Daly. The two collaborated on the Broadway musicals Piccadilly to Broadway (1920) and For Goodness' Sake (1922), and jointly composed the score for Our Nell (1923). This was the beginning of a long friendship. Daly was a frequent arranger, orchestrator and conductor of Gershwin's music, and Gershwin periodically turned to him for musical advice.[22]

Musical, Europe and classical music, 1924–1928[]

In 1924, Gershwin composed his first major work, Rhapsody in Blue, for orchestra and piano. It was orchestrated by Ferde Grofé and premiered by Paul Whiteman's Concert Band, in New York. It subsequently went on to be his most popular work, and established Gershwin's signature style and genius in blending vastly different musical styles, including jazz and classical, in revolutionary ways.

Since the early 1920s Gershwin had frequently worked with the lyricist Buddy DeSylva. Together they created the experimental one-act jazz opera Blue Monday, set in Harlem. It is widely regarded as a forerunner to the groundbreaking Porgy and Bess introduced in 1935. In 1924, George and Ira Gershwin collaborated on a stage musical comedy Lady Be Good, which included such future standards as "Fascinating Rhythm" and "Oh, Lady Be Good!".[23] They followed this with Oh, Kay! (1926),[24] Funny Face (1927) and Strike Up the Band (1927 and 1930). Gershwin allowed the song, with a modified title, to be used as a football fight song, "Strike Up The Band for UCLA".[25]

In the mid-1920s, Gershwin stayed in Paris for a short period, during which he applied to study composition with the noted Nadia Boulanger, who, along with several other prospective tutors such as Maurice Ravel, turned him down, afraid that rigorous classical study would ruin his jazz-influenced style.[26] Maurice Ravel's rejection letter to Gershwin told him, "Why become a second-rate Ravel when you're already a first-rate Gershwin?" While there, Gershwin wrote An American in Paris. This work received mixed reviews upon its first performance at Carnegie Hall on December 13, 1928, but it quickly became part of the standard repertoire in Europe and the United States.[27]

New York, 1929–1935[]

In 1929, the Gershwin brothers created Show Girl;[28] the following year brought Girl Crazy,[29] which introduced the standards "Embraceable You", sung to Ginger Rogers, and "I Got Rhythm". 1931's Of Thee I Sing became the first musical comedy to win the Pulitzer Prize for Drama; the winners were George S. Kaufman, Morrie Ryskind, and Ira Gershwin.[30]

Gershwin spent the summer of 1934 on Folly Island in South Carolina after he was invited to visit by the author of the novel Porgy, DuBose Heyward. He was inspired to write the music to his opera Porgy and Bess while on this working vacation.[31] Porgy and Bess was considered another American classic by the composer of Rhapsody in Blue — even if critics could not quite figure out how to evaluate it, or decide whether it was opera or simply an ambitious Broadway musical. "It crossed the barriers," per theater historian Robert Kimball. "It wasn't a musical work per se, and it wasn't a drama per se – it elicited response from both music and drama critics. But the work has sort of always been outside category."[32]

Last years, 1936–37[]

After the commercial failure of Porgy and Bess, Gershwin moved to Hollywood, California. In 1936, he was commissioned by RKO Pictures to write the music for the film Shall We Dance, starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Gershwin's extended score, which would marry ballet with jazz in a new way, runs over an hour. It took Gershwin several months to compose and orchestrate.

Gershwin had a ten-year affair with composer Kay Swift, whom he frequently consulted about his music. The two never married, although she eventually divorced her husband James Warburg in order to commit to the relationship. Swift's granddaughter, Katharine Weber, has suggested that the pair were not married because George's mother Rose was "unhappy that Kay Swift wasn't Jewish".[33] The Gershwins' 1926 musical Oh, Kay was named for her.[34] After Gershwin's death, Swift arranged some of his music, transcribed several of his recordings, and collaborated with his brother Ira on several projects.[35]

Illness and death[]

Early in 1937, Gershwin began to complain of blinding headaches and a recurring impression that he smelled burning rubber. On February 11, 1937, he performed his Piano Concerto in F in a special concert of his music with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra under the direction of French maestro Pierre Monteux.[36] Gershwin, normally a superb pianist in his own compositions, suffered coordination problems and blackouts during the performance. He was at the time working on other Hollywood film projects while living with Ira and his wife Leonore in their rented house in Beverly Hills. Leonore Gershwin began to be disturbed by George's mood swings and his seeming inability to eat without spilling food at the dinner table. She suspected mental illness and insisted he be moved out of their house to lyricist Yip Harburg's empty quarters nearby, where he was placed in the care of his valet, Paul Mueller. The headaches and olfactory hallucinations continued.

On the night of July 9, 1937, Gershwin collapsed in Harburg's house, where he had been working on the score of The Goldwyn Follies. He was rushed to Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Los Angeles,[37] and fell into a coma. Only then did his doctors come to believe that he was suffering from a brain tumor. Leonore called George's close friend Emil Mosbacher and explained the dire need to find a neurosurgeon. Mosbacher immediately called pioneering neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing in Boston, who, retired for several years by then, recommended Dr. Walter Dandy, who was on a boat fishing in Chesapeake Bay with the governor of Maryland. Mosbacher called the White House and had a Coast Guard cutter sent to find the governor's yacht and bring Dandy quickly to shore.[38] Mosbacher then chartered a plane and flew Dandy to Newark Airport, where he was to catch a plane to Los Angeles;[39] by that time, Gershwin's condition was critical and the need for surgery was immediate.[38] In the early hours of July 11, doctors at Cedars removed a large brain tumor, believed to have been a glioblastoma, but Gershwin died on the morning of July 11, 1937, at the age of 38.[40] The fact that he had suddenly collapsed and become comatose after he stood up on July 9 has been interpreted as brain herniation with Duret haemorrhages.[40]

Gershwin's friends and followers were shocked and devastated. John O'Hara remarked: "George Gershwin died on July 11, 1937, but I don't have to believe it if I don't want to."[41] He was interred at Westchester Hills Cemetery in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. A memorial concert was held at the Hollywood Bowl on September 8, 1937, at which Otto Klemperer conducted his own orchestration of the second of Gershwin's Three Preludes.[42]

Musical style and influence[]

Gershwin was influenced by French composers of the early twentieth century. In turn Maurice Ravel was impressed with Gershwin's abilities, commenting, "Personally I find jazz most interesting: the rhythms, the way the melodies are handled, the melodies themselves. I have heard of George Gershwin's works and I find them intriguing."[43] The orchestrations in Gershwin's symphonic works often seem similar to those of Ravel; likewise, Ravel's two piano concertos evince an influence of Gershwin.

George Gershwin asked to study with Ravel. When Ravel heard how much Gershwin earned, Ravel replied with words to the effect of, "You should give me lessons." (Some versions of this story feature Igor Stravinsky rather than Ravel as the composer; however Stravinsky confirmed that he originally heard the story from Ravel.)[44]

Gershwin's own Concerto in F was criticized for being related to the work of Claude Debussy, more so than to the expected jazz style. The comparison did not deter him from continuing to explore French styles. The title of An American in Paris reflects the very journey that he had consciously taken as a composer: "The opening part will be developed in typical French style, in the manner of Debussy and Les Six, though the tunes are original."[45]

Gershwin was intrigued by the works of Alban Berg, Dmitri Shostakovich, Igor Stravinsky, Darius Milhaud, and Arnold Schoenberg. He also asked Schoenberg for composition lessons. Schoenberg refused, saying "I would only make you a bad Schoenberg, and you're such a good Gershwin already."[46] (This quote is similar to one credited to Maurice Ravel during Gershwin's 1928 visit to France – "Why be a second-rate Ravel, when you are a first-rate Gershwin?") Gershwin was particularly impressed by the music of Berg, who gave him a score of the Lyric Suite. He attended the American premiere of Wozzeck, conducted by Leopold Stokowski in 1931, and was "thrilled and deeply impressed".[47]

Russian Joseph Schillinger's influence as Gershwin's teacher of composition (1932–1936) was substantial in providing him with a method of composition. There has been some disagreement about the nature of Schillinger's influence on Gershwin. After the posthumous success of Porgy and Bess, Schillinger claimed he had a large and direct influence in overseeing the creation of the opera; Ira completely denied that his brother had any such assistance for this work. A third account of Gershwin's musical relationship with his teacher was written by Gershwin's close friend Vernon Duke, also a Schillinger student, in an article for the Musical Quarterly in 1947.[48]

What set Gershwin apart was his ability to manipulate forms of music into his own unique voice. He took the jazz he discovered on Tin Pan Alley into the mainstream by splicing its rhythms and tonality with that of the popular songs of his era. Although George Gershwin would seldom make grand statements about his music, he believed that "true music must reflect the thought and aspirations of the people and time. My people are Americans. My time is today."[49]

In 2007, the Library of Congress named its Prize for Popular Song after George and Ira Gershwin. Recognizing the profound and positive effect of popular music on culture, the prize is given annually to a composer or performer whose lifetime contributions exemplify the standard of excellence associated with the Gershwins. On March 1, 2007, the first Gershwin Prize was awarded to Paul Simon.[50]

Recordings and film[]

Early in his career, under both his own name and pseudonyms, Gershwin recorded more than one hundred and forty player piano rolls which were a main source of his income. The majority were popular music of the period and a smaller proportion were of his own works. Once his musical theatre-writing income became substantial, his regular roll-recording career became superfluous. He did record additional rolls throughout the 1920s of his main hits for the Aeolian Company's reproducing piano, including a complete version of his Rhapsody in Blue.

Compared to the piano rolls, there are few accessible audio recordings of Gershwin's playing. His first recording was his own "Swanee" with the Fred Van Eps Trio in 1919. The recorded balance highlights the banjo playing of Van Eps, and the piano is overshadowed. The recording took place before "Swanee" became famous as an Al Jolson specialty in early 1920.

Gershwin recorded an abridged version of Rhapsody in Blue with Paul Whiteman and his orchestra for the Victor Talking Machine Company in 1924, soon after the world premiere. Gershwin and the same orchestra made an electrical recording of the abridged version for Victor in 1927. However, a dispute in the studio over interpretation angered Whiteman and he left. The conductor's baton was taken over by Victor's staff conductor Nathaniel Shilkret.[51]

Gershwin made a number of solo piano recordings of tunes from his musicals, some including the vocals of Fred and Adele Astaire, as well as his Three Preludes for piano. In 1929, Gershwin "supervised" the world premiere recording of An American in Paris with Nathaniel Shilkret and the Victor Symphony Orchestra. Gershwin's role in the recording was rather limited, particularly because Shilkret was conducting and had his own ideas about the music. When it was realized that no one had been hired to play the brief celeste solo, Gershwin was asked if he could and would play the instrument, and he agreed. Gershwin can be heard, rather briefly, on the recording during the slow section.

Gershwin appeared on several radio programs, including Rudy Vallee's, and played some of his compositions. This included the third movement of the Concerto in F with Vallee conducting the studio orchestra. Some of these performances were preserved on transcription discs and have been released on LP and CD.

In 1934, in an effort to earn money to finance his planned folk opera, Gershwin hosted his own radio program titled Music by Gershwin. The show was broadcast on the NBC Blue Network from February to May and again in September through the final show on December 23, 1934. He presented his own work as well as the work of other composers.[52] Recordings from this and other radio broadcasts include his Variations on I Got Rhythm, portions of the Concerto in F, and numerous songs from his musical comedies. He also recorded a run-through of his Second Rhapsody, conducting the orchestra and playing the piano solos. Gershwin recorded excerpts from Porgy and Bess with members of the original cast, conducting the orchestra from the keyboard; he even announced the selections and the names of the performers. In 1935 RCA Victor asked him to supervise recordings of highlights from Porgy and Bess; these were his last recordings.

A 74-second newsreel film clip of Gershwin playing I Got Rhythm has survived, filmed at the opening of the Manhattan Theater (now The Ed Sullivan Theater) in August 1931.[53] There are also silent home movies of Gershwin, some of them shot on Kodachrome color film stock, which have been featured in tributes to the composer. In addition, there is newsreel footage of Gershwin playing "Mademoiselle from New Rochelle" and "Strike Up the Band" on the piano during a Broadway rehearsal of the 1930 production of Strike Up the Band. In the mid-30s, "Strike Up The Band" was given to UCLA to be used as a football fight song, "Strike Up The Band for UCLA". The comedy team of Clark and McCullough are seen conversing with Gershwin, then singing as he plays.

In 1945, the film biography Rhapsody in Blue was made, starring Robert Alda as George Gershwin. The film contains many factual errors about Gershwin's life, but also features many examples of his music, including an almost complete performance of Rhapsody in Blue.

In 1965, Movietone Records released an album MTM 1009 featuring Gershwin's piano rolls of the titled George Gershwin plays RHAPSODY IN BLUE and his other favorite compositions. The B-side of the LP featured nine other recordings.

In 1975, Columbia Records released an album featuring Gershwin's piano rolls of Rhapsody In Blue, accompanied by the Columbia Jazz Band playing the original jazz band accompaniment, conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas. The B-side of the Columbia Masterworks release features Tilson Thomas leading the New York Philharmonic in An American In Paris.

In 1976, RCA Records, as part of its "Victrola Americana" line, released a collection of Gershwin recordings taken from 78s recorded in the 1920s and called the LP Gershwin plays Gershwin, Historic First Recordings (RCA Victrola AVM1-1740). Included were recordings of Rhapsody in Blue with the Paul Whiteman Orchestra and Gershwin on piano; An American in Paris, from 1927 with Gershwin on celesta; and Three Preludes, "Clap Yo' Hands" and Someone to Watch Over Me", among others. There are a total of ten recordings on the album. At the opening ceremony of the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, Rhapsody in Blue was performed in spectacular fashion by many pianists.

The soundtrack to Woody Allen's 1979 film Manhattan is composed entirely of Gershwin's compositions, including Rhapsody in Blue, "Love is Sweeping the Country", and "But Not for Me", performed by both the New York Philharmonic under Zubin Mehta and the Buffalo Philharmonic under Michael Tilson Thomas. The film begins with a monologue by Allen, in the role of a writer, describing a character in his book: "He adored New York City ... To him, no matter what the season was, this was still a town that existed in black and white and pulsated to the great tunes of George Gershwin."

In 1993, two audio CDs featuring piano rolls recorded by Gershwin[54] were issued by Nonesuch Records through the efforts of Artis Wodehouse, and entitled Gershwin Plays Gershwin: The Piano Rolls.[55]

In October 2009, it was reported by Rolling Stone that Brian Wilson was completing two unfinished compositions by George Gershwin,[56] released as Brian Wilson Reimagines Gershwin on August 17, 2010, consisting of ten George and Ira Gershwin songs, bookended by passages from Rhapsody in Blue, with two new songs completed from unfinished Gershwin fragments by Wilson and band member Scott Bennett.

Compositions[]

Orchestral

- Rhapsody in Blue for piano and orchestra (1924)

- Concerto in F for piano and orchestra (1925)

- An American in Paris for orchestra (1928)

- Dream Sequence/The Melting Pot for chorus and orchestra (1931)

- Second Rhapsody for piano and orchestra (1931), originally titled Rhapsody in Rivets

- Cuban Overture for orchestra (1932), originally entitled Rumba

- March from "Strike Up the Band" for orchestra (1934)

- Variations on "I Got Rhythm" for piano and orchestra (1934)

- Catfish Row for orchestra (1936), a suite based on music from Porgy and Bess

- Shall We Dance (1937), a movie score feature-length ballet

Solo piano

- Three Preludes (1926)

- George Gershwin's Song-book (1932), solo piano arrangements of 18 songs

Operas

- Blue Monday (1922), one-act opera

- Porgy and Bess (1935) at the Colonial Theatre in Boston[57]

London musicals

- Primrose (1924)

Broadway musicals

- George White's Scandals (1920–1924), featuring, at one point, the 1922 one-act opera Blue Monday

- Lady, Be Good (1924)

- Tip-Toes (1925)

- Tell Me More! (1925)

- Oh, Kay! (1926)

- Strike Up the Band (1927)

- Funny Face (1927)

- Rosalie (1928)

- Treasure Girl (1928)

- Show Girl (1929)

- Girl Crazy (1930)

- Of Thee I Sing (1931)

- Pardon My English (1933)

- Let 'Em Eat Cake (1933)

- My One and Only (1983), an original 1983 musical using previously written Gershwin songs

- Crazy for You (1992), a revised version of Girl Crazy

- Nice Work If You Can Get It (2012), a musical with a score by George and Ira Gershwin

- An American in Paris, a musical that ran on Broadway from April 2015 to October 2016

Films for which Gershwin wrote original scores

- Delicious (1931), an early version of the Second Rhapsody and one other musical sequence was used in this film, the rest were rejected by the studio

- Shall We Dance (1937), original orchestral score by Gershwin, no recordings available in modern stereo, some sections have never been recorded (Nominated- Academy Award for Best Original Song: They Can't Take That Away from Me)

- A Damsel in Distress (1937)

- The Goldwyn Follies (1938), posthumously released

- The Shocking Miss Pilgrim (1947), uses previously unpublished songs

Legacy[]

Estate[]

Gershwin died intestate, and his estate passed to his mother.[58] The estate continues to collect significant royalties from licensing the copyrights on his post-Rhapsody in Blue work.[citation needed] The estate supported the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (that extended the U.S. 75-year copyright protection an additional 20 years) because its 1923 cutoff date was shortly before Gershwin had begun to create his most popular works. The copyrights on all Gershwin's solo works expired at the end of 2007 in the European Union, based on its life-plus-70-years rule, and in the U.S. on January 1, 2020, on Gershwin's pre-1925 work.[59]

In 2005, The Guardian determined using "estimates of earnings accrued in a composer's lifetime" that George Gershwin was the wealthiest composer of all time.[60]

The George and Ira Gershwin Collection, much of which was donated by Ira and the Gershwin family estates, resides at the Library of Congress.[61]

In September 2013, a partnership between the estates of Ira and George Gershwin and the University of Michigan was created and will provide the university's School of Music, Theatre, and Dance access to Gershwin's entire body of work, which includes all of Gershwin's papers, compositional drafts, and scores.[62] This direct access to all of his works provides opportunities to musicians, composers, and scholars to analyze and reinterpret his work with the goal of accurately reflecting the composers' vision in order to preserve his legacy.[63] The first fascicles of The Gershwin Critical Edition, edited by Mark Clague, are expected in 2017; they will cover the 1924 jazz band version of Rhapsody in Blue, An American in Paris and Porgy and Bess.[64][needs update]

Awards and honors[]

- In 1937, Gershwin received his sole Academy Award nomination for Best Original Song at the 1937 Oscars for "They Can't Take That Away from Me", written with his brother Ira for the 1937 film Shall We Dance. The nomination was posthumous; Gershwin died two months after the film's release.[65]

- In 1985, the Congressional Gold Medal was awarded to George and Ira Gershwin. Only three other songwriters, George M. Cohan, Harry Chapin, and Irving Berlin, have received this award.[66][67]

- In 1998 a special Pulitzer Prize was posthumously awarded to Gershwin "commemorating the centennial year of his birth, for his distinguished and enduring contributions to American music."[68]

- The George and Ira Gershwin Lifetime Musical Achievement Award was established by UCLA to honor the brothers for their contribution to music and for their gift to UCLA of the fight song "Strike Up the Band for UCLA".

- In 2006, Gershwin was inducted into the Long Island Music Hall of Fame.[69]

Namesakes[]

- The Gershwin Theatre on Broadway is named after George and Ira.[70]

- The Gershwin Hotel in the Flatiron District of Manhattan in New York City was named after George and Ira.

- In Brooklyn, George Gershwin Junior High School 166 is named after him.[71]

- One of Holland America Line's ships, MS Koningsdam, has a Gershwin Deck (Deck 5)[72]

- The Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song

Biopic[]

- The 1945 biographical film Rhapsody in Blue starred Robert Alda as George Gershwin.

Portrayals in other media[]

- Since 1999, Hershey Felder has produced a one-man show with him portraying George Gershwin Alone, which has played over 3,000 performances and was winner of two 2007 Ovation Awards.[73] In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Felder launched a global live-streaming Hershey Felder Presents: Live from Florence featuring a performance of "Hershey Felder as George Gershwin Alone" in September 2020.[74]

- Paul Rudd portrays an imaginary friend based on George Gershwin, said to be his creator's favorite composer, in the 2015 series finale of the Irish sitcom Moone Boy, "Gershwin's Bucket List".

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jablonski 1987, pp. 24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pollack 2006, pp. fn707.

- ^ ObituaryVariety, July 14, 1937, page 70

- ^ "George Gershwin, Composer, is Dead; Master of Jazz Succumbs in Hollywood at 38 After Operation for Brain Tumor". The New York Times. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^ Carp L. George Gershwin-illustrious American composer: his fatal glioblastoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1979; 3: 473–478.

- ^ "Russian Heritage Museum: George Gershwin". russianheritagemuseum.com. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ Hyland 2003, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Pollack 2006, p. 3.

- ^ Jablonski 1987, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Jablonski 1987, pp. 24: "Morris Gershovitz moved his family...to Brooklyn, where he had found an unprepossessing two-story brick house at 242 Snedicker Avenue... In this house on September 26, 1898, Jacob Gershwine (as George's birth certificate reads) was delivered...The name change may have been Morris's idea; it is possible that by the time he married he had streamlined his name to "Gershvin," and so would the doctor have been informed. Gershwine in a Jewish community would still be pronounced Gershvin.

- ^ Pollack 2006, pp. fn707: "Gershwin's birth certificate reads, 'Jacob Gershwine'; [Frances Gershwin] suggests that Morris's brother, Aaron, first changed the family name, though the latter gave his name in the 1920 census as 'Gershvin.'"

- ^ Jablonski 1987, pp. 25: "Eight-year old George (no one in the family remembers calling him Jake or Jacob)..."

- ^ Jablonski 1987, pp. 10, 29–31.

- ^ Pollack 2006.

- ^ Andrew Rosenberg, Martin Dunford (2012). The Rough Guide to New York City. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-4053-9022-4.

- ^ "Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress: George Gershwin". Jewish Virtual Library. 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2013. As quoted by Abraham J. Karp (1991) From the Ends of the Earth: Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress, p. 351, ISBN 0-8478-1450-5.

- ^ Schwartz, Charles (1973). Gershwin, His Life and Music. New York, NY: Da Capo Press, Inc. p. 14. ISBN 0-306-80096-9.

- ^ Hyland 2003, p. 13.

- ^ Hyland 2003, p. 14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Venezia, Mike (1994). Getting to Know the World's Greatest Composers: George Gerswhin. Chicago IL: Childrens Press.

- ^ Slide, Anthony. The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1994. p. 111.

- ^ Pollack 2006, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Lady, Be Good at the Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved August 22, 2011

- ^ Oh, Kay! at the Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved August 22, 2011

- ^ Strike Up the Band at the Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved August 22, 2011

- ^ Jablonski 1987, pp. 155–170.

- ^ Jablonski 1987, pp. 178–180.

- ^ Show Girl at the Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved August 22, 2011

- ^ Girl Crazy at the Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved August 22, 2011

- ^ "Drama". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ "Gershwin on Folly: Summertime and the livin' was easy". FollyBeach.com. December 6, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Grigsby Bates, Karen. 70 Years of Gershwin's 'Porgy and Bess'" npr.org, October 10, 2005

- ^ Sidney Offit (September–October 2011). "Sins of Our Fathers (and Grandmothers)". Moment Magazine. Archived from the original on October 11, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ Hyland 2003, p. 108.

- ^ Kay Swift biography (Kay Swift Memorial Trust). kayswift.com. Retrieved December 28, 2007.

- ^ Pollack 2006, p. 353.

- ^ Jablonski, Edward. "George Gershwin; He Couldn't Be Saved" (Letter to Editor), The New York Times, October 25, 1998, Section 2; Page 4; Column 5

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jablonski, Edward. Gershwin. New York: Doubleday, 1987. p. 323.

- ^ Jablonski, Edward. Gershwin. New York: Doubleday, 1987. p. 324.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mezaki, Takahiro (2017). "George Gershwin's death and Duret haemorrhage". The Lancet. 390 (10095): 646. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31623-9. PMID 28816130.

- ^ "Broad Street". Broadstreetreview.com. February 27, 2007. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ Pollack 2006, p. 392.

- ^ Mawer & Cross 2000, p. 42.

- ^ Arthur Rubinstein, My Many Years; Merle Armitage, George Gershwin; Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft, Dialogues and a Diary, all quoted in Norman Lebrecht, The Book of Musical Anecdotes

- ^ Hyland 2003, p. 126.

- ^ Norman Lebrecht, The Book of Musical Anecdotes

- ^ Howard Pollack, George Gershwin: His Life and Work, p. 145. Retrieved June 20, 2016

- ^ Dukelsky, Vladimir (Vernon Duke), "Gershwin, Schillinger and Dukelsky: Some Reminiscences", The Musical Quarterly, Volume 33, 1947, 102–115 doi:10.1093/mq/XXXIII.1.102

- ^ "George Gershwin" Archived May 4, 2010, at the Wayback Machine balletmet.org, (Compiled February 2000). Retrieved April 20, 2010

- ^ "Paul Simon: The Library Of Congress Gershwin Prize For Popular Song", PBS article

- ^ Peyser 2007, p. 133.

- ^ Pollack 2006, p. 163.

- ^ Jablonski & Stewart 1973, p. 70.

- ^ George Gershwin and the player piano 1915–1927 Archived July 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. richard-dowling.com. Retrieved December 28, 2007.

- ^ Yanow, Scott." 'Gershwin Plays Gershwin: The Piano Rolls' Overview" allmusic.com. Retrieved August 22, 2011

- ^ "Brian Wilson Will Complete Unfinished Gershwin Compositions" rollingstone.com, October 2009

- ^ Jablonski & Stewart 1973, pp. 25, 227–229..

- ^ Pollack 2006, p. 7.

- ^ "1924 Copyrighted Works To Become Part Of The Public Domain", NPR, December 30, 2019

- ^ Scott, Kirsty.Gershwin leads composer rich list The Guardian, August 29, 2005. Retrieved December 28, 2007.

- ^ "George and Ira Gershwin collection, 1895-2008". The Library of Congress. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- ^ "U-M to become epicenter of research on music of George & Ira Gershwin". Michigan News. 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ^ "Toward a Go-To Gershwin Edition". New York Times. 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2013.

- ^ "The Gershwin Critical Edition – Senza Sordino". March 21, 2016. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^ "1937 Song" Archived December 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine oscars.org. Retrieved August 22, 2011

- ^ "In Performance at the White House:The Library of Congress:Gershwin Prize" pbs.org. Retrieved April 15, 2010

- ^ "Congressional Gold Medal Recipients (1776 to Present)" Office of the Clerk, US House of Representatives (clerk.house.gov). Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ^ "The 1998 Pulitzer Prize Winners: Special Awards and Citations". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "George Gershwin | Long Island Music Hall of Fame". www.limusichalloffame.org. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ^ "History of the Gershwin Theater" Archived March 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine gershwin-theater.com. Retrieved August 22, 2011

- ^ Richardson, Clem (October 23, 2009). "Tonya Lewis brings start power and true perfect to 'only-place-to-be' party". Daily News. New York. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- ^ "Koningsdam". www.hollandamerica.com. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ Favre, Jeff (November 4, 2019). "Self-Starter: Hershey Felder and George Gershwin Alone". backstage.com. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ "Hershey Felder as 'George Gershwin Alone'". Hershey Felder Presents. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

Citations[]

- Hyland, William G. (2003). George Gershwin : A New Biography. Praeger. ISBN 0-275-98111-8.

- Jablonski, Edward; Stewart, Lawrence D. (1973). The Gershwin Years: George and Ira (2nd ed.). Garden City, New Jersey: Doubleday. ISBN 0-306-80739-4.

- Jablonski, Edward (1987). Gershwin. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-19431-5.

- Kimball, Robert & Alfred Simon. The Gershwins (1973), Athenium, New York, ISBN 0-689-10569-X

- Mawer, Deborah; Cross, Jonathan, eds. (2000). The Cambridge Companion to Ravel. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64856-4.

- Peyser, Joan (2007). The Memory of All That:The Life of George Gershwin. Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-1-4234-1025-6.

- Pollack, Howard (2006). George Gershwin. His Life and Work. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24864-9.

- Rimler, Walter. A Gershwin Companion (1991), Popular Culture ISBN 1-56075-019-7

- Rimler, Walter George Gershwin : An Intimate Portrait (2009), University of Illinois Press, ISBN 0-252-03444-9

- Sloop, Gregory. "What Caused George Gershwin's Untimely Death?" Journal of Medical Biography 9 (February 2001): 28–30

Further reading[]

- Alpert, Hollis. The Life and Times of Porgy and Bess: The Story of an American Classic (1991). Nick Hern Books. ISBN 1-85459-054-5

- Feinstein, Michael. Nice Work If You Can Get It: My Life in Rhythm and Rhyme (1995), Hyperion Books. ISBN 0-7868-8220-4

- Jablonski, Edward. Gershwin Remembered (2003). Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-43-8

- Rosenberg, Deena Ruth. Fascinating Rhythm: The Collaboration of George and Ira Gershwin (1991). University of Michigan Press ISBN 978-0-472-08469-2

- Sheed, Wilfred. The House That George Built: With a Little Help from Irving, Cole, and a Crew of About Fifty (2007). Random House. ISBN 0-8129-7018-7

- Suriano, Gregory R. (Editor). Gershwin in His Time: A Biographical Scrapbook, 1919–1937 (1998). Diane Pub Co. ISBN 0-7567-5660-X

- Weber, Katharine. "The Memory Of All That: George Gershwin, Kay Swift, and My Family's Legacy of Infidelities" (2011). Crown Publishers, Inc./Broadway Books ISBN 978-0-307-39589-4

- Wyatt, Robert and John Andrew Johnson (Editors). The George Gershwin Reader (2004). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513019-7

Historiography[]

- Carnovale, Norbert. George Gershwin: a Bio-Bibliography (2000. ) Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-26003-2 ISBN 0-313-26003-6

- Muccigrosso, Robert, ed., Research Guide to American Historical Biography (1988) 5:2523-30

External links[]

| Archives at | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| How to use archival material |

Media related to George Gershwin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to George Gershwin at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to George Gershwin at Wikiquote

Quotations related to George Gershwin at Wikiquote- Official website

- Free scores by George Gershwin at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- George Gershwin at the Internet Broadway Database

- George Gershwin at IMDb

- George and Ira Gershwin Collection at the Library of Congress

- George Gershwin Bio at Jewish-American Hall of Fame

- George Gershwin Collection at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- The Gershwin Initiative at The University of Michigan

- George Gershwin oral histories at Oral History of American Music

- George Gershwin

- 1898 births

- 1937 deaths

- 20th-century American composers

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century classical composers

- 20th-century classical pianists

- 20th-century jazz composers

- American classical composers

- American classical pianists

- American film score composers

- American jazz composers

- American jazz pianists

- American jazz songwriters

- American male classical composers

- American male film score composers

- American male jazz composers

- American male jazz musicians

- American male pianists

- American musical theatre composers

- American opera composers

- American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- Broadway composers and lyricists

- Burials at Westchester Hills Cemetery

- Classical musicians from New York (state)

- Composers for piano

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Deaths from brain tumor

- Deaths from cancer in California

- Jazz-influenced classical composers

- Jazz musicians from New York (state)

- Jewish American classical composers

- Jewish American classical musicians

- Jewish American film score composers

- Jewish American jazz composers

- Jewish American songwriters

- Jewish classical composers

- Jewish classical pianists

- Jewish jazz musicians

- Jewish opera composers

- Male classical pianists

- Male musical theatre composers

- Male opera composers

- Musicians from Brooklyn

- People from Morningside Heights, Manhattan

- People from the East Village, Manhattan

- Porgy and Bess

- Pulitzer Prize winners

- Pupils of Henry Cowell

- Songwriters from New York (state)

- Vaudeville performers

- Victor Records artists