Great Resignation

| Resignations in the United States | |

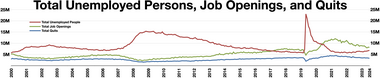

| Resignation rates plummeted in the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, but returned to pre-pandemic levels in July 2020 and began reaching record numbers in April 2021.[1] | |

The Great Resignation, also known as the Big Quit,[2][3] is an ongoing economic trend in which employees have voluntarily resigned from their jobs en masse, beginning in early 2021, primarily in the United States. Possible causes include wage stagnation amid rising cost of living, economic freedom provided by COVID-19 stimulus payments, long-lasting job dissatisfaction, and safety concerns of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some economists have described the Great Resignation as akin to a general strike.[4][5][6]

The term was coined by Anthony Klotz, a professor of management at Mays Business School at Texas A&M University, who predicted the mass exodus in May 2021.[7][8][9][10]

Background[]

In the twenty years preceding February 2021, roughly a year after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States resignation rate never surpassed 2.4% of the total workforce per month.[11] High quit rates indicate worker confidence in the ability to get higher paying jobs, which typically coincides with high economic stability, an abundance of people working,[12] and low unemployment rates.[13][14] Conversely, during periods of high unemployment, resignation rates tend to decrease as hire rates also decrease. For example, during the Great Recession, the U.S. quit rate decreased from 2.0% to 1.3% as the hire rate fell from 3.7% to 2.8%.[11]

Resignation rates in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic initially followed this pattern. In March and April 2020, a record 13.0 and 9.3 million workers (8.6% and 7.2%) were laid off, and the quit rate subsequently fell to a seven-year low of 1.6%.[11] Much of the layoffs and resignations were driven by women, who disproportionately work in industries that were affected most by the lockdowns, like service industries and childcare.[13][15][16]

As the pandemic has continued, however, workers have paradoxically quit their jobs in large numbers. This is despite continued labor shortages and high unemployment.[17][18]

Causes[]

The COVID-19 pandemic has allowed workers to rethink their careers, work conditions, and long-term goals.[12][19] As many workplaces attempted to bring their employees in-person, workers desired the freedom of remote work due to the COVID-19 pandemic as well as schedule flexibility, which was the primary reason to look for a new job of the majority of those studied by Bankrate in August 2021.[20] Additionally, many workers, particularly in younger cohorts, are seeking to gain a better work–life balance.[21] Millions of people are also suffering disabilities from long COVID, altering their ability or desire to work.[22]

Restaurants and hotels, industries that require in-person interactions, have been hit the hardest by waves of resignations.[23] COVID-19 stimulus payments and rises in unemployment benefits have allowed those who rely on low-wage jobs for survival to stay home, although places where unemployment benefits were rolled back did not see significant job creation as a result.[23][12][24] On the other hand, many workers who are dissatisfied with their jobs report that they cannot resign due to economic barriers, many of these workers being people of color.[25] Sekou Siby, president and CEO of the US nonprofit Restaurant Opportunities Center United, commented, "There's more competition across industries, so workers are feeling more empowered than ever before, but that doesn't mean everyone is able to leave their current jobs."[25]

According to a study conducted by Adobe, the exodus is being driven by Millennials and Generation Z, who are more likely to be dissatisfied with their work. More than half of Gen Z reported planning to seek a new job within the next year.[26] Harvard Business Review found that the cohort between 30 and 45 years old had the greatest increase in resignation rates.[27] Racial minority, low-wage, and frontline workers are also more dissatisfied with their work in the United States, according to the asset management firm Mercer.[28]

An IMF working paper by Carlo Pizzinelli and Ippei Shibata focused on causes of the loss in employment within the US and UK labor markets in comparison to pre-COVID-19 levels.[29] They identified job mismatch (that is, mismatch between the areas where people search for work and where the most vacancies are) as playing a "modest" role, being less significant than in the wake of the global financial crisis. The effect of the pandemic on women, sparking the so-called "She-cession", was deemed as accounting for some 16% of the total US employment shortfall but little to none of the shortfall in the UK. Meanwhile, the authors attribute 35% of the shortfall in both the UK and US to older workers (aged 55–74) withdrawing from the labor force.[29] On the other side, Harvard Business Review reported that resignation rates actually fell for those aged 60–70 years old (in comparison to 2020 rates).[27]

Impacts[]

United States[]

In April 2021, as COVID-19 vaccination rates increased, evidence began emerging that the Great Resignation was beginning in the United States. That month, a record 4.0 million Americans quit their jobs.[30][18] In June 2021, approximately 3.9 million American workers quit their jobs.[31] Resignations are consistently the most prevalent in the South, where 2.9% of the workforce voluntarily left their jobs in June, followed by the Midwest (2.8%) and the West (2.6%). The Northeast is the most stable region, with 2.0% of workers quitting in June.[32]

In October 2021, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that food service workers' quit rates rose to 6.8%, which is well above the industry average of 4.1% over the last 20 years and still higher than the industry's quit peaks of 5% in 2006 and 2019.[33] The retail industry had the second highest quit rates at 4.7%.[34] From the start of the pandemic to November 2021, approximately one in five healthcare workers quit their jobs.[35]

According to Microsoft's 2021 Work Trend Index, more than 40% of the global workforce were considering quitting their job in 2021.[36] According to a PricewaterhouseCoopers survey conducted in early August 2021, 65% of employees said they were looking for a new job and 88% of executives said their company was experiencing higher turnover than normal.[37] A Deloitte study published in Fortune magazine in October 2021 found that among Fortune 1000 companies, 73% of CEOs anticipated the work shortage would disrupt their businesses over the next 12 months, 57% believed attracting talent is among their company's biggest challenges, and 35% already expanded benefits to bolster employee retention.[38]

Wage growth has jumped; in December 2021, wage growth reached 4.5%, the highest since June 2001.[39][40] Some employers in the fast food industry, like McDonalds, are providing more benefits, like college scholarships and healthcare benefits, to buy back workers.[41] Public sector jobs have had higher worker retention as compared to private sector jobs, largely due to stronger benefits like paid family leave.[42]

Amidst the Great Resignation, a strike wave known as Striketober began, with over 100,000 American workers participating in or preparing for strike action.[6][43] While discussing Striketober, some economists described the Great Resignation as workers participating in a general strike against poor working conditions and low wages.[6]

Europe[]

A survey of 5,000 people in Belgium, France, the UK, Germany and the Netherlands by HR company SD Worx found that employees in Germany had the most COVID-19-related resignations, with 6.0% of the workers leaving their jobs. This was followed by the United Kingdom with 4.7%, the Netherlands with 2.9%, and France with 2.3%. Belgium had the least number of resignations with 1.9%.[44]

Some preliminary data show an increase in the number of quits in Italy, starting in the second quarter of 2021. The registered increase was not only in absolute terms, but also in terms of quit rate (computed as quits over employed population) and of quit share (computed as quits over total contract terminations).[45]

China[]

A similar social protest movement is occurring in China, referred to as tang ping (Chinese: 躺平; lit. 'lying flat'). It started roughly during the same time as the Great Resignation, in April 2021.[46] It is a rejection of societal pressures to overwork, such as in the 996 working hour system. Those who participate in tang ping instead choose to "lie down flat and get over the beatings" via a low-desire, more indifferent attitude towards life.

India[]

India has witnessed large scale resignations across many sectors of the economy.[47] The information technology sector in particular witnessed massive attrition, with over a million resignations in 2021.[48][49][50][51]

Australia[]

Australia is seeing an unprecedented number of workers leaving their jobs for better pay and working conditions.[52] In IT, salaries have increased well over 10% in many areas.[53]

See also[]

- COVID-19 pandemic

- COVID-19 recession

- American Rescue Plan Act of 2021

- Striketober

- Labor history of the United States

- Refusal of work

- Millennial socialism

- 2021 global supply chain crisis

- r/antiwork

References[]

- ^ "JOLTS". Economic Policy Institute. Archived from the original on 2021-11-12. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- ^ Curtis, Lisa. "Why The Big Quit Is Happening And Why Every Boss Should Embrace It". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2021-07-16. Retrieved 2021-07-16.

- ^ Rosenberg, Jacob. "Workers got fed up. Bosses got scared. This is how the Big Quit happened". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ Jacobson, Lindsey (2022-02-04). "The 'Great Resignation' is a reaction to 'brutal' U.S. capitalism: Robert Reich". CNBC. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ "Perspective | Are we witnessing a 'General Strike' in our own time?". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ a b c "'Striketober' is showing workers' rising power – but will it lead to lasting change?". The Guardian. 2021-10-23. Archived from the original on 2021-10-24. Retrieved 2021-10-24.

- ^ Cohen, Arianne (May 10, 2021). "How to Quit Your Job in the Great Post-Pandemic Resignation Boom". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on July 8, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

Ready to say adios to your job? You're not alone. "The great resignation is coming," says Anthony Klotz, an associate professor of management at Texas A&M University who's studied the exits of hundreds of workers.

- ^ "Transcript: The Great Resignation with Molly M. Anderson, Anthony C. Klotz, PhD & Elaine Welteroth". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2021-11-10. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- ^ Kaplan, Juliana. "The psychologist who coined the phrase 'Great Resignation' reveals how he saw it coming and where he sees it going. 'Who we are as an employee and as a worker is very central to who we are.'". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 2021-10-25. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- ^ Beilfuss, Lisa (December 30, 2021). "Covid Drove Workers to Quit. Here's Why From the Person Who Saw It Coming". Barron's.

- ^ a b c "JOLTS". Economic Policy Institute. Archived from the original on 2021-09-01. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ^ a b c HSU, ANDREA (June 24, 2021). "As The Pandemic Recedes, Millions Of Workers Are Saying 'I Quit'". NPR. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27.

- ^ a b "What the Increase in Quit Rates During a Recession Means for Women—and How to Counteract It - Ms. Magazine". msmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2021-08-18. Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ "For some, quitting a job during COVID-19 may make sense". Marketplace. 2020-09-16. Archived from the original on 2021-09-01. Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ "Gender Differences in Sectors of Employment". Women in the States. Archived from the original on 2021-09-01. Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ "Women have been hit hard by the coronavirus labor market: Their story is worse than industry-based data suggest". Economic Policy Institute. Archived from the original on 2021-09-29. Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ Horsley, Scott; Hsu, Andrea (4 June 2021). "Hiring Picked Up Last Month, But The Economy Still Needs More Workers". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2021-09-01. Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ a b "U.S. job openings, quits hit record highs in April". Reuters. 2021-06-08. Archived from the original on 2021-08-31. Retrieved 2021-08-31.

- ^ "Is the great resignation a great rethink?". The Seattle Times. 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ Reinicke, Carmen (2021-08-25). "The 'Great Resignation' is likely to continue, as 55% of Americans anticipate looking for a new job". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- ^ "What's fueling 'The Great Resignation' among younger generations?". Fortune. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- ^ Beilfuss, Lisa. "Where Are the Workers? Millions Are Sick With 'Long Covid.'". Barrons. Barrons. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Hotels And Restaurants That Survived Pandemic Face New Challenge: Staffing Shortages". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- ^ "Millions Lose Jobless Benefits Today. It Doesn't Mean They'll Be Rushing Back To Work". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved 2021-10-09.

- ^ a b Aviles, Gwen (December 4, 2021). "The so-called 'Great Resignation' isn't a reality for many workers of color". Insider Inc. Retrieved 2022-02-01.

- ^ Smart, Tim (August 26, 2021). "Study: Gen Z, Millennials Driving 'The Great Resignation'". USNews. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2021.

- ^ a b Cook, Ian (2021-09-15). "Who Is Driving the Great Resignation?". Harvard Business Review. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- ^ "the truth about what employees want" (PDF). Mercer. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Pizzinelli, Carlo; Ippei, Shibata (January 19, 2022). "Has COVID-19 Induced Labor Market Mismatch? Evidence from the US and the UK". www.imf.org. Retrieved 2022-02-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Liu, Jennifer (2021-06-09). "4 million people quit their jobs in April, sparked by confidence that they can find better work". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2021-06-30. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ Pressman, Aaron; Gardizy, Anissa (2021-06-27). "'A giant game of musical chairs': Waves of workers are changing jobs as the pandemic wanes". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 2021-06-28. Retrieved 2021-06-28.

- ^ "Table 4. Quits levels and rates by industry and region, seasonally adjusted". www.bls.gov. 2021-09-08. Archived from the original on 2021-09-10. Retrieved 2021-09-14.

- ^ Sozzi, Brian (15 October 2021). "The Great Resignation is ripping through the restaurant industry". Yahoo! Finance. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Lufkin, Bryan (28 October 2021). "What we're getting wrong about the 'Great Resignation'". BBC.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Yong, Ed (November 16, 2021). "Why Health-Care Workers Are Quitting in Droves". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ "The Work Trend Index: The Next Great Disruption Is Hybrid Work—Are We Ready?". Microsoft.com. Microsoft Corporation. 2021. Archived from the original on July 7, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

41% of employees are considering leaving their current employer this year and 46% say they're likely to move because they can now work remotely.

- ^ "PwC US Pulse Survey: Next in work". PricewaterhouseCoopers. PwC. Archived from the original on 2021-08-23. Retrieved 2021-08-23.

- ^ Lambert, Lance (21 October 2021). "The Great Resignation is no joke". Fortune. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ "Wage Growth Tracker". www.atlantafed.org. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ Rosenberg, Jacob. "Workers got fed up. Bosses got scared. This is how the Big Quit happened". Mother Jones. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ Reliey, Laura (2022). "Restaurant workers are quitting in droves, this is how they are being lured back". The Washington Post.

- ^ Institute, MissionSquare Research (2022-02-01). "Public Sector Benefits Can Offer a Hiring and Retention Advantage During the Great Resignation, According to MissionSquare Research Institute". GlobeNewswire News Room. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ Quinn, Bryan (October 15, 2021). "'Striketober' in US as organised labour makes a post-pandemic comeback". France 24. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ^ LLB Staff, Reporter (2021-08-11). "Pandemic fuels 'Great Resignation' in UK job market as workforce rethinks career priorities". LondonLovesBusiness. Archived from the original on 2021-08-19. Retrieved 2021-08-19.

- ^ Armillei, Francesco (2021-10-25). "Si apre la stagione delle grandi dimissioni?". lavoce-info. Archived from the original on 2021-11-09. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ^

- Kaplan, Juliana (3 November 2021). "The labor shortage is reshaping the economy and how people talk about work. Here's a glossary of all the new phrases that sum up workers' frustration with their deal, from 'lying flat' to 'antiwork.'". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- Siqi, Ji; Huifeng, He; Peach, Brian (24 October 2021). "What is 'lying flat', and why are Chinese officials standing up to it?". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- Tharoor, Ishaan (18 October 2021). "Analysis | The 'Great Resignation' goes global". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "The 'great attrition': It's a difficult time to be a boss". The New Indian Express. 21 November 2021.

- ^ "Employee attrition a big headache for IT companies. Can they tide over it?". Mint. 25 August 2021.

- ^ "Despite bonuses and salary hikes, India's IT sector will see over a million resignations this year". The Times of India. 28 October 2021.

- ^ Vanamali, Krishna Veera (21 October 2021). "What's behind record staff exits at Indian IT giants?". Business Standard.

- ^ "Attrition in IT sector to cross 1 million this year'". The Hindu. 27 September 2021.

- ^ "Australia is seeing a 'great reshuffle' not a 'great resignation' in workforce". The Conversation. 6 February 2022.

- ^ "The Great Resignation drives tech wages higher: Can startups keep up?". . 11 November 2021.

External links[]

- Economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

- 2021 in economics

- 2021 in international relations

- Economic history