Hastert Rule

The Hastert Rule, also known as the "majority of the majority" rule, is an informal governing principle used in the United States by Republican Speakers of the House of Representatives since the mid-1990s to maintain their speakerships[1] and limit the power of the minority party to bring bills up for a vote on the floor of the House.[2] Under the doctrine, the Speaker will not allow a floor vote on a bill unless a majority of the majority party supports the bill.[3]

Under House rules, the Speaker schedules floor votes on pending legislation. The Hastert Rule says that the Speaker will not schedule a floor vote on any bill that does not have majority support within their party—even if the majority of the members of the House would vote to pass it. The rule keeps the minority party from passing bills with the assistance of a minority of majority party members. In the House, 218 votes are needed to pass a bill; if 200 Democrats are the minority and 235 Republicans are the majority, the Hastert Rule would not allow 200 Democrats and 100 Republicans together to pass a bill, because 100 Republican votes is short of a majority of the majority party, so the Speaker would not allow a vote to take place.[4]

The Hastert Rule is an informal rule and the Speaker is not bound by it; they may break it at their discretion. Speakers have at times broken the Hastert Rule and allowed votes to be scheduled on legislation that lacked majority support within the Speaker's own party. Hastert described the rule as being "kind of a misnomer" in that it "never really existed" as a rule.

Origins[]

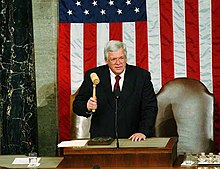

The Hastert Rule's introduction is credited to former House Speaker Dennis Hastert; however, Newt Gingrich, who directly preceded Hastert as Speaker (1995–1999), followed the same rule.[5] The notion of the rule arose out of a debate in 2006 over whether Hastert should bring an immigration reform bill to the House floor after it had been passed by the Senate. “It was pretty obvious at that point that it didn’t have the votes to move it out, especially in the Judiciary Committee,” he said later. “It was pretty well stacked with people who weren’t willing to move.”[6]

Speakers' views and use of the policy[]

- Tip O'Neill (Speaker from 1977–1987): According to John Feehery, a Hastert aide and speechwriter who coined the term "majority of the majority," O'Neill let the Republicans "run the floor" because he didn't have the votes and because he believed that if he gave President Ronald Reagan "enough rope, he would end up strangling himself."[7]

- Tom Foley: (1989–1995): In 2004, Foley said, "I think you don't want to bring bills to the floor that a majority of your party is opposed to routinely but sometimes when a great issue is at stake, I think you need to do that."[8]

- Newt Gingrich (1995–1999): Although the majority-of-the-majority rule had not been articulated at the time, Gingrich followed it in practice.[5]

- Dennis Hastert (1999–2007): In 2003 Hastert said, "On occasion, a particular issue might excite a majority made up mostly of the minority. Campaign finance is a particularly good example of this phenomenon. [But] the job of speaker is not to expedite legislation that runs counter to the wishes of the majority of his majority."[9] During his speakership, he broke the Hastert Rule a dozen times.[10] In mid-2013 he said, "If you start to rely on the minority to get the majority of your votes, then all of a sudden you’re not running the shop anymore."[11] Later that year, Hastert said, "The Hastert Rule never really existed. It's a non-entity as far as I'm concerned." Reflecting on his time as speaker, he said, "This wasn’t a rule. I was speaking philosophically at the time.... The Hastert Rule is kind of a misnomer."[12]

- Nancy Pelosi (2007–2011, 2019–present): In 2003 Pelosi, then the House Minority Leader under Speaker Hastert, decried the Hastert Rule as a partisan attempt to marginalize elected members of the Democratic Party in Congress.[1] In May 2007 Pelosi said, "I'm the Speaker of the House...I have to take into consideration something broader than the majority of the majority in the Democratic Caucus."[13] She also said at that time, "I would encourage my colleagues not to be proposing resolutions that say 'the majority of the majority does this or that.' We have to talk it out, see what is possible to get a job done. And as I say, we do that together."[13] Pelosi's former chief of staff, George Crawford, expanded upon this saying, "On the larger issue of the 'majority of the majority,' she has talked about that for quite a while. She does want the minority party to engage in the legislative process... That's the kind of Speakership she wants."[13] However, when Pelosi became speaker for the second time, she succeeded in obtaining a rules package that would require a majority of the majority to remove her from power. In other words, Republicans could not unite with a minority of Democrats to vacate her from the Speakership.[14]

- John Boehner (2011–2015):

Speaker John Boehner violated the Hastert Rule at least six times.

Speaker John Boehner violated the Hastert Rule at least six times.- In December 2012 Boehner told his caucus in a conference call, "I'm not interested in passing something with mostly Democrat votes" and that did not have the support of the majority of the Republican caucus.[15][16] Nonetheless, Boehner allowed a vote on January 1, 2013 on the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (also known as the "fiscal cliff bill") with only 85 out of 241 Republicans in favor (a support level of only 35%) and the bill passed with the support of 90% of Democrats (172 out of 191).[17][18] The bill's passage marked the first time in more than ten years that a measure passed a Republican-controlled House when opposed by a majority of House Republicans.[19] In response, former House Speaker Hastert criticized Boehner for not adhering to the "majority of the majority" governing principle by saying, "Maybe you can do it once, maybe you can do it twice, but when you start making deals when you have to get Democrats to pass the legislation, you are not in power anymore."[20][21]

- Two weeks later, on January 15, 2013, Boehner allowed a vote on aid to victims of Hurricane Sandy to take place without the support of a majority of the Republican caucus.[22] The vote passed with 241 votes, but only 49 of the votes were from Republicans or a mere 21% of the majority.[23] Since then some notable Republicans have publicly questioned whether the "majority of the majority" rule is still viable or have proposed jettisoning it altogether.[23][24][25]

- In spite of all the criticism, on February 28, 2013 Boehner brought a third bill for a vote on the floor of the house which did not have support of majority of Republicans. The bill, an extension of the Violence Against Women Act, received the vote of only 38% of the Republicans in the House of Representatives.[26]

- On April 9, 2013, the "rule" was violated a fourth time, on a bill about federal acquisition of historic sites. The bill was passed with more than two thirds of the House vote but without a majority of the GOP caucus.[27] Shortly thereafter, Boehner said, "Listen: It was never a rule to begin with. And certainly my prerogative – my intention is to always pass bills with strong Republican support."[28]

- On October 16, 2013, Boehner again violated the rule by allowing a floor vote to reopen the government and raise the debt ceiling. The House voted 285 to 144 less than three hours after the Senate overwhelmingly passed the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2014. The "yea" votes consisted of 198 Democrats and only 87 Republicans, less than 40% of the conference.[29]

- On February 11, 2014, Boehner broke the rule by allowing a floor vote on a "clean" debt ceiling bill. The bill passed the house 221-201, with only 28 Republicans voting "yea" along with 193 Democrats.[30]

- Paul Ryan (2015–2019): Paul Ryan promised his caucus that he would apply the Hastert rule to immigration bills proposed during his tenure as Speaker, although conflicting reports have also interpreted his statements as a more blanket application of the rule.[31][32] Throughout his speakership, Ryan did not violate the majority-of-the-majority rule.[citation needed]

Commentary[]

Commentators' views about the Hastert Rule are generally negative. The New York Times reported in 2016 that the rule "has come to be seen as a structural barrier to compromise."[33]

George Crawford, writing in The Hill, observes that the rule restricts legislative proposals to those approved by the majority of the Speaker's caucus. When combined with a systematic effort to marginalize the influence of the minority power, it can lead to a breakdown of the legislative process, radicalization of the members of the minority party, and legislation that does not reflect the broadest view and area of agreement.[2]

It also all but ensures that the Speaker will keep their job.[5]

Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute, an expert on Congress, opposes the rule, arguing that it is a major reason why bills passed on a bipartisan basis in the Senate are often not later introduced in the House.[4] Ornstein notes that the speaker is the leader of their party but is also "a constitutional officer" who is "ratified by the whole House" and as such has a duty to put the House ahead of their party at crucial times.[9]

Ezra Klein, while at The Washington Post, wrote that the Hastert Rule is "more of an aspiration" than a rule and that codifying it as a formal rule would be detrimental to House Republicans, as it would prevent them from voting against bills that the Republican caucus wanted passed but that a majority of Republicans wanted to oppose for ideological or political reasons.[34]

Matthew Yglesias, writing in Slate, has contended that the rule, while flawed, is better than the alternatives and that the dynamic prior to its adoption was "a weird kind of super-empowerment of the Rules committee that allowed it to arbitrarily bottle up proposals."[35]

Senator Angus King of Maine, an independent, as well as commentators such as Rex Huppke of The Chicago Tribune and Eric Black of MinnPost have blamed the Hastert Rule for the government shutdown of October 2013.[36][37] Huppke added facetiously, "Here's the fun part: the Hastert Rule isn't an official rule, or an official anything. It's just a made-up concept, like bipartisanship or polite discourse."[38]

CNBC's Ben White has called the Hastert Rule "perhaps the most over-hyped phenomena in politics," since Republican speakers "have regularly violated the rule when it was in their interest to do so."[39]

Discharge petition[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (February 2014) |

A discharge petition signed by 218 members (or more) from any party is the only way to force consideration of a bill that does not have the support of the Speaker. However, discharge petitions are rarely successful, as a member of the majority party defying their party's leadership by signing a discharge petition can expect retribution from the leadership.

See also[]

- Condorcet paradox

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ball, Molly (July 21, 2013). "Even the Aide Who Coined the Hastert Rule Says the Hastert Rule Isn't Working". The Atlantic.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crawford, George (September 19, 2007). "The 'majority of the majority' doctrine". The Hill.

- ^ Sherman, Jake; Allen, Jonathan (July 30, 2011). "Boehner seeks 'majority of the majority'". Politico.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Welna, David (December 2, 2012). "The 3 Unofficial GOP Rules That Are Making A Deficit Deal Even Harder". NPR.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Feehery, John (August 1, 2011). "Majority of the majority". The Hill.

- ^ Meckler, Laura (January 30, 2014). "Former Speaker Hastert Calls for Immigration Overhaul". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Feehery, John (January 16, 2013). "Rules Are Made to Be Broken". The Feehery Theory.

- ^ "Congress Reaches Deal on Intelligence Bill". PBS NewsHour. December 6, 2004.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Babington, Charles (November 27, 2004). "Hastert Launches a Partisan Policy". The Washington Post.

- ^ Noah, Timothy (Sep 27, 2013). "The absurdity of the Hastert Rule". MSNBC. Retrieved Oct 3, 2013.

- ^ Strong, Jonathan (July 3, 2013). "Immigration and the Hastert Rule". National Review.

- ^ Clift, Eleanor (October 3, 2013). "Denny Hastert Disses the 'Hastert Rule': It 'Never Really Existed'". The Daily Beast.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Davis, Susan (May 29, 2007). "Pelosi Brings End to 'Hastert Rule'". Roll Call. Archived from the original on 2015-06-22.

- ^ Chaffetz, Jason (22 June 2019). "Why Nancy Pelosi will not be fired until at least 2021". Fox News.

- ^ Sherman, Jake; Bresnahan, John (December 27, 2012). "Fiscal cliff action shifts to Senate". Politico.

- ^ Newhauser, Daniel; Shiner, Meredith (December 27, 2012). "Boehner 'Not Interested' in Bill That Most of GOP Would Reject". Roll Call.

- ^ Hook, Janet; Boles, Corey; Hughes, Siobhan (January 2, 2013). "Congress Passes Cliff Deal". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Tomasky, Michael (January 2, 2013). "The End of the Hastert Rule". The Daily Beast.

- ^ Tumulty, Karen; Wallsten, Peter (January 2, 2013). "Has the 'fiscal cliff' fight changed how Washington works?". The Washington Post.

- ^ Johnson, Luke (January 3, 2013). "Dennis Hastert Warns John Boehner About Leadership After Fiscal Cliff Deal". The Huffington Post.

- ^ Robillard, Kevin (January 3, 2013). "Dennis Hastert warns Boehner on his 'rule'". Politico.

- ^ Goddard, Taegan (January 16, 2013). "Did Democrats finally find a way to bypass House Republicans?". The Week.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Newhauser, Daniel (January 16, 2013). "'Hastert Rule' Takes Body Blows With Sandy, Cliff Votes". Roll Call.

- ^ Yglesias, Matthew (January 17, 2013). "House GOP Considering New Strategy on Fiscal Issues: Surrender!". Slate.

- ^ Frum, David (January 16, 2013). "Speaker Boehner, Ditch the Hastert Rule". The Daily Beast.

- ^ Russert, Luke (February 28, 2013). "Boehner eschews Hastert rule for third time". NBC News.

- ^ Willis, Derek (April 11, 2013). "Tracking Hastert Rule Violations in the House". The New York Times.

- ^ Blake, Aaron (April 11, 2013). "Boehner on Hastert Rule: 'It was never a rule to begin with'". The Washington Post.

- ^ Everett, Burgess; Sherman, Jake; Raju, Manu (October 17, 2013). "Boehner taps Dems to push budget deal across finish line". Politico.

- ^ Cillizza, Chris (February 16, 2014). "Does John Boehner still want to be House speaker?". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Paul Ryan Pledges: No Immigration Reform under Obama". National Review. Retrieved 2017-07-21.

- ^ Evans, Garrett (2016-04-28). "House conservatives push for strong majority of majority rule". TheHill. Retrieved 2017-07-21.

- ^ Carl Hurse (May 2, 2016). "Now, Dennis Hastert Seems an Architect of Dysfunction as Speaker". New York Times. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ^ Klein, Ezra (June 18, 2013). "Is Boehner bluffing on the Hastert rule? Even he doesn't know". The Washington Post.

- ^ Yglesias, Matthew (January 2, 2013). "Boehner to Reid: "Go F—— Yourself"; Why Party Cartels Matter". Slate.

- ^ "King: 'Hastert rule' added to gridlock". Associated Press. October 17, 2013.

- ^ Black, Eric (October 2, 2013). "What's behind the shutdown? Put 'Hastert Rule' and Constitution on your list". MinnPost.

- ^ Huppke, Rex (October 17, 2013). "We'll miss the countdown to catastrophe". The Chicago Tribune.

- ^ White, Ben (November 25, 2013). "A winter of bitter discontent in DC? Maybe not". CNBC.

External links[]

- "House Votes Violating the "Hastert Rule"". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016.

- Political terminology of the United States

- Parliamentary procedure

- Terminology of the United States Congress

- 1999 introductions

- 106th United States Congress