Henry Beaufoy Merlin

Henry Beaufoy Merlin | |

|---|---|

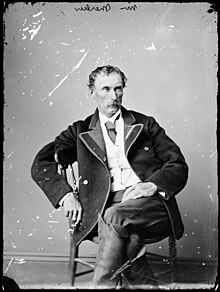

Portrait of Henry Beaufoy Merlin, 1872–1873, attributed to the American and Australian Photographic Company, State Library of New South Wales, ON 4 Box 30 No 68 | |

| Born | Henry Beaufoy Merlin Baptised 29 March 1830 |

| Died | 27 September 1873 |

| Occupation | Theatrical entrepreneur, illustrator, photographer |

| Years active | 1851–1873 |

| Known for | American and Australasian Photographic Company, Gold Rush and Holtermann Exposition photographs |

Henry Beaufoy Merlin (1830–1873) was an Australian photographer, showman, illusionist and illustrator.[2] In the 1850s he worked as a theatrical showman and performer in Sydney, Newcastle and Maitland. In 1863 he was the first person to introduce Pepper's ghost to Australia. After this, he took up photography and between 1869 and 1872 turned the American Australasian Photographic Company into one of the most respected studios in Australia. Between 1872 and 1873 he worked extensively documenting the goldfields and mining towns of New South Wales. In 1873, as an employee of Bernhardt Holtermann, he photographed Sydney and many rural New South Wales towns. He died on 27 September 1873.[3]

Early life[]

Merlin was born in Norfolk, England, the son of a chemist, Frederick Merlin, and his wife, Ann Harriet (nee Beaufoy). He was baptised in Wells-next-the-Sea in March 1830.[4] Merlin and his mother arrived in Sydney from London on 8 December 1848.[2]

In 1851 Ann Harriet married Henry John Forster.[5] The Sydney Morning Herald records that the bride's name was Anne Harriett Murlin, daughter of Benjamin Beaufoy.[6] After his mother's marriage to Foster, Merlin took to using a number of different names before finally settling on Beaufoy Merlin, leading to some confusion around his early history.[7]

Theatrical Showman[]

In May 1853, Henry Murlin took out a licence to establish a Marionette theatre, ‘executed with mechanical figures.’[8] Merlin opened in the old Olympic Circus building in Castlereagh Street and a month later went on the road with the ‘burlesque theatre’ holding a number of shows, including a performance of Bombastes Furioso by William Rhodes.[9]

By 1855 Merlin had set up an amateur theatre in Maitland where he started referring to himself as Henry B. Muriel. Around the middle of 1856 Merlin opened a ‘beautiful little’ theatre in High Street named the ‘Queen's Theatre’ which accommodated 300 people.[3] The Following year, after the Maitland theatre burned to the ground, he moved to Newcastle where he worked as a manager, actor and painter of scenery for ‘The Newcastle Theatre.’[10]

After a few shows, Merlin left Newcastle and, in May 1857, he applied for a license to exhibit panoramas in Sydney. A year later he was still in Sydney and in June 1858, he opened a new exhibition at the Lyceum Theatre, Sydney.[11]

Merlin's Indian panorama, painted by himself and a Mr. Guy, seems to have involved a series of scrolling panoramic scenes and projections over which a narrator would recount tales, offer scientific snippets, sing songs and offer humorous vignettes.[12] Within a few weeks of its, opening Merlin added a new scene to the production titled The Storming of Delhi, from the Cashmere [sic.] Gate, presumably highlighting events from the Indian rebellion the year before.[13] At the end of November 1858 Merlin sold the ‘Indian Panorama’.</ref>[14]

While details of Merlin's general movements are sketchy, over the next few years but in 1863 he was back in England. In January Henry Beaufoy Merlin married Louisa Eleanor Foster at the church of St Mary in Bow, Middlesex, and it was under this name he and Louisa moved back to Australia.[15][16] By July Merlin was settled in Melbourne where he embarked on a new theatrical enterprise which projected a spectral illusion onto a stage.[17]

This spectral illusion, popularly known as Pepper's ghost, used a series of angled sheets of glass to project a ghost onto the stage alongside the actors. A provisional patent had been lodged in England by John Henry Pepper and Henry Dircks in February 1863, and this may have been why it was possible for Merlin to lodge one here in Australia.[18][19]

Merlin's consortium was the first to successfully perform the trick for the theatre here in Australia and the first play they chose was a popular drama entitled The Castle Spectre. It was well received according to contemporary accounts.[20]

In late September he was presenting ‘The Ghost’ in Castlemaine, Victoria, but with no theatrical accompaniment. Instead, the illusion was presented by Merlin himself a part of a lecture on spiritualism.[21] When a presentation of ‘The Ghost’ arrived at the Victoria Theatre in Adelaide in October 1863, it was Woollaston and a Mr. Solomon who were being credited as the main instigators.[22]

Photographer 1865–1872[]

On 21 January 1865, H. Merlin, opened the ‘Kyneton Photographic Studio’ in Piper Street, Kyneton, a small town in northern Victoria. The studio was completed at considerable expense and advertised instantaneous portraits, landscape and stereoscopic views, enlargements from carte de visites in crayon and in oil as well as an operating room, ‘constructed on the principle recently designed by Mr Matheson of the Crystal Palace, and until the present occasion, never introduced to this colony.[23]

Importantly, Merlin was already advertising his services to take photographs of public buildings and private residences, ‘at moderate terms and on the shortest notice’, as this would become one of the features of American and Australasian Photographic Company.[23] However it seems Merlin had dangerously extended his credit to set up the studio and without enough customers was, by May 1865, filing for insolvency. In particular, he pointed out how ‘he had been deprived by the owner of the use of certain necessary implements he had on hire for the purpose of carrying on his business.’[24][25]

By December 1865 the insolvency proceedings had been resolved and, with no more creditors, Merlin appears to have moved to Ballarat where his mother, now a widow, was also living.[26] Included in a description of the Ballarat District Exhibition for 1866, photographs by Roberts and Merlin of Ballarat are mentioned alongside Mrs. Forster's wax flowers and fruits which were described as being, ‘so beautiful that it is difficult to wish for anything better.’[27]

By February 1869 his contemporaries were touting him as a successful travelling landscape photographer and he was working on an album of landscapes for His Excellency the Governor of Victoria as well as taking photographs for the Prince of Wales who was to visit Sydney in the same year.[28]

In June 1869, he was at Emerald Hill giving a ‘highly-interesting and instructive lecture The Pilgrim's Progress, illustrated with beautiful dissolving views.’ His experiences over this period must have convinced him that there was money to be made taking landscape and architectural views but the failure of his studio in Kyneton and his prior experience as a travelling showman seems to have encouraged him to set up a different kind of photographic business.[12] On 21 June 1869, he formed the American and Australasian [sometimes recorded as Australian] Photographic Company (AAPC).

A company called the American and Australian Photographic Company has been formed, for the purpose of carrying out photographic operations on an extensive scale. The company have an office in the city, but the headquarters of the landscape department is at Emerald Hill. The company commenced business on Monday.[29]

Initially, the office in Melbourne was located at 73 Little Collins Street but it seems Merlin opened a second office, at 4 Barrack Street, Sydney, in September 1869.[30] Although the AAPC offices were located in the city, much of the business was being done in country areas. The AAPC business model adopted a new methodology to increase efficiency and mitigate the costs of travelling to country towns. And this seems in part shaped by the many years Merlin had spent promoting his theatrical events.[31]

Firstly, advertisements in local papers would alert the residents that a representative of the company would be arriving. Once there, the photographer would take a photograph of every house and building. The negatives would then be sent back to head office where they could be stored. As orders came in, either through the AAPC photographer or AACP representatives in the town, prints were made and sent to the purchaser.[32]

This approach appears to have been set in place almost from the inception of the company. In September 1869, the company arrived in Beechworth where advertisements in the Oven and Murray Advertiser stated the town's residences would be photographed.[33]

As the year drew to a close, Merlin still appears to have been handling the bulk of the photography work.[34] The AAPC advertisements from this period also make it clear he was making his way towards Sydney through Emerald Hill (June), Beechworth (September), Shepparton (October) and Wangaratta (November). In December, he was at the El Dorado Goldfields where he photographed the turning of the sod for the Devon Company's first mine shaft.[35]

By February 1870 he was in New South Wales visiting Yass where he made good on his advertised promises to photograph every house. Not only were the pictures done rapidly but they were also done with, with more than usual excellence.[36] Although the photographs were for sale at the time they were taken the company representatives did not press their sale while on location. Instead, the negatives were stored at the head offices in Melbourne and Sydney and prints put on display there. From here they could be ordered as required.[36] Agents were also employed by the company to sell photographs on commission.[3]

The Australian Eclipse Expedition 1871[]

In October, Merlin left Sydney to take photographs of Wollongong and Kiama leaving Charles Bayliss in charge of the ‘supervision of the Landscape Department’ and attending to all orders, weather permitting.[37] This arrangement may have been a way to shore up the company before Merlin's final adventure for 1871. On 27 November, Merlin left Sydney on the steamship Governor Blackall as a part of the Australian Solar Eclipse Expedition bound for North Queensland. Accompanying him on board were a ‘who's who’ of Australia's natural historians and scientists all of whom were travelling to Cape Sidmouth to view the solar eclipse on 12 December. Unfortunately, after they had set up their instruments on Eclipse Island the day proved too overcast and, even though he continued to expose the plates Merlin described their trip had been in vain.[38]

On the return journey, Merlin experimented with taking a series of coastline views of the Whitsunday Passage and succeeded in recording a considerable portion of it. These he thought would prove useful to the mariner as they reproduced the ‘elevations, depressions, projections, &c, with an accuracy impossible in hand-drawings.’[39] Merlin arrived back in Sydney on Christmas Eve, ‘in time to hear the joyous Christmas bells ring out.’[40]

The Gold Rush Photographs[]

The new year initially seemed to be business as usual for the AAPC, with operators at work in Wagga Wagga and Gympie.[41][42] But on 5 February he announced he was retiring from management of the New South Wales branch of the Company. He was replaced by Mr. Carlisle who continued to use photographic staff from the company.[43]

He then packed up his camera and equipment and headed off to the newly discovered goldfields at Hill End, Tambaroora and Gulgong near Bathurst, New South Wales. This arrangement does not mean Merlin left the company, in fact he continued to supply Carlisle with negatives of Hill End to print.[44]

Merlin's photographs of shops, hotels, theatres, mines and batteries were supplemented by more traditional portraits of the townsfolk taken in the AAPC studio set up in Tambaroora and the temporary one set up at Hill End.[45] The earlier work of the AACP photographers, including Merlin, had focused on landscape views. While these sometimes-included people in the streets and outside their houses this feature became even more obvious in Merlin's goldfield photos. Here people seem to have been actively encouraged to pose in front of their cottage, mine or shop and, thus, most of these 1872 views include owners, families and managers posed in front of their buildings.[46]

Contemporary newspapers cite Merlin as the photographer responsible for the 1872 landscape views taken on theNew South Wales Goldfields[47] and these photographs remain his most lasting legacy.[3] By 4 May he had spent time at both Hill End and Tambaroora and had taken over 100 views some of which made their way to the Metropolitan Intercolonial Exhibition in Sydney.[48] Less than a week later the Evening News was effusive in its praise of Merlin's images of Hawkins Hill and twenty large views, one dozen lesser views, and sixty smaller photographs of every scene of interest as well as the principle machinery at work. The whole series made up a valuable portrayal of the extensive mining operations at the locations.[49] The Evening News also made it clear how unique Merlin's enterprise was,

.. these splendid photographs, will, we hope, reimburse the spirited artist for the great difficulties undergone and expense he incurred is carrying out his object in so mountainous and broken a country. So far as we are aware nothing of the like nature has ever before been successfully accomplished in similar circumstances.’[49]

While many of the shots were taken of the buildings and streets others taken in the goldfields themselves required a great deal more effort. One of these, depicting the mines at Hawkins Hill, was reproduced in the Town and Country Journal on 18 May 1872, where the journalist, possibly Merlin himself, describes how the photograph was only possible after erecting a series of stages in the highest trees above the thousand foot deep gully. The camera and photographer then climbed up to the stage to photograph the mines nearly two miles away on the other side of the gully.[50]

Holtermann Exposition[]

By 1872 The Star of Hope Gold Mining Company was mining one of the richest veins of gold in Hawkins Hill and this had made its manager, Bernard Holtermann, very wealthy.[51] Merlin and Holtermann's relationship came to the fore when the largest piece of reef-gold in the world was discovered in the Star of Hope mine on 19 October 1872.[52] Holtermann approached Merlin, who photographed it before it was sent to the crusher and took several photographs of Holtermann and his partner Beyer. Then on 30 October, Merlin wrote a long biographical article praising Holtermann's hard work and persistence, which had kept the mine running in the years before they struck gold.[53] In November, he photographed the cakes of pure gold made from crushing the huge piece of reef gold.[54]

By the end of December, Holtermann had left the Hill End to set himself up in his new home on the North Shore of Sydney. It was also around this time that Merlin seems to have inspired Holtermann to start a new project.[55] On 1 January 1873 a number of advertisements appeared in papers across the country describing Holtermann's new and ambitious scheme to promote Australia's industrial resources and to seek submissions from interested parties before the proposed opening in eight months time.[56]

Holtermann engaged Merlin to take panoramas and views of all the towns and gold-fields in the colonies which would then be used to create albums of each town and gold-field, containing statistical information and other valuable matter. These photographs were to be presented as large transparent pictures using a new process invented by Merlin.[57] As the year progressed Holtermann remained continued to support Merlin in his photographic endeavours. In March, the Governor of New South Wales, Hercules Robinson, visited Hill End and Merlin captured the banners strung across the street to welcome him.[58]

In April, Merlin was in Bathurst photographing the town for Holtermann.[59] And, on 5 July, the Town and Country Journal posted an article by the ‘Photographic Artist of Holtermann's Exhibition,’ presumably Merlin, which extolled the beauty of the countryside, and the described the 102 main buildings in the town as well as the character of its inhabitants.[60] By the end of July, he was back in Sydney, taking more photographs for the exhibition and working on a series of large three-foot transparent photographs, hundreds of which were intended for Holtermann's Exposition.[61] The positive transparencies were created by enlarging his original negatives and their size was noted by those that saw the early examples produced by Merlin.[62]

One reason for the coverage in the news may have been due to a deputation of the New South Wales Commissioners for the International Exhibition, who were meeting with the Colonial Secretary to discuss setting up a permanent exhibition building in London. This proposal fell through, even though it was potentially a good fit for Holtermann's Exposition collection.[63] Being of German origin, Holtermann may have been looking to display at the Vienna Exhibition but when this opened in September 1873 there were no displays from New South Wales.[64] Regardless of these setbacks, Merlin worked with his normal diligence preparing his collections for the Exposition without knowing when they would finally open.[65] His primary focus continued to be the work for Holtermann but he also found time to write journalistic articles for the papers. In August 1873 he produced a series of articles on the recent discoveries made by the expedition of HMS Basilisk to New Guinea.[66]

At the same time, he continued with his photographic work and his image of the French warship Atalante at Fitzroy Dock on Cockatoo Island, Sydney, is one Merlin himself acknowledged as among his best works.[67] Soon after this, Merlin left Sydney to photograph the townships of Orange and Dubbo. His account of this journey, which appeared in the Town and Country Journal, praised the people and the climate and reads almost like a caption for one of the proposed album of views for Holtermann's Exposition.[68]

Death[]

On 27 September 1873 Merlin died after a very short illness at his home in Little Abercrombie Street, Leichhardt, Sydney.[69] The cause was an ‘inflammation of the lungs supervening upon the epidemic (a kind of influenza) which has lately been so general in Sydney.’[70]

The Evening News, which recorded his death, also gave an insight into the character of this highly motivated and successful man:

Mr. Merlin had won the esteem of a wide circle of friends by his kindness of heart, and singularly unpretentious, straight-forward, and genial character. Energetic, temperate, and active to a remarkable degree, his unexpected decease [sic.] will surprise as well as grieve all to whom he was known. As a photographic artist, he was almost without rival, while his talents as a writer were of a superior kind, although the want of leisure greatly interfered with his literary tastes.[71]

Legacy[]

Whilst Merlin was well known as a photographer at the time of his death,[72] it was not until 1951 that the extent of his photographic achievement, and that of his assistant, Charles Bayliss, was realised with the discovery of approximately 3,000 glass photographic negatives neatly packed in cedar and metal boxes.[73] The find was subsequently titled the Holtermann collection in honour of Bernhardt Holtermann, who had financed the enterprise of taking the photographs.

After Merlin's death his wife and children returned to England.[74] Merlin's mother found herself in financial distress following his death, and funds were collected to assist her.[75]

Merlin's lasting legacy is the Holtermann Collection. As Keast Burke put it "Australia must forever owe a deep debt of gratitude to Beaufoy Merlin, for his photography proved to be the true historian of that time and place—incomparable, authentic[,] unchallengeable."[74] In 2013 the Holtermann collection of photographs was listed on the UNESCO memory of the world.[76]

References[]

- ^ 1841 England Census

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bradshaw, Richard (2005). "Merlin, Henry Beaufoy (1830–1873)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Supplementary. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 6 June 2014 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Geoff Barker, Henry Beaufoy Merlin Showman and Photographer, 2018

- ^ England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538–1975

- ^ Bradshaw also notes that Merlin's step-father, Henry Forster, had sometimes appeared in reports ar ‘Foster’. Richard Bradshaw, ‘Henry Beaufoy Merlin’ Archived 6 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2005

- ^ Unknown, ‘Family Notices’, The Sydney Morning Herald, (12 March 1851), 3. and R. Bradshaw, ‘The Merlin of the South’, Australasian Drama Studies, no 7, Oct 1985, 87.

- ^ R. Bradshaw, ‘The Merlin of the South’, Australasian Drama Studies, no 7, Oct 1985, 87.

- ^ These shows, popular in London, were a mixture of technology, farce and music incorporating live actors, puppets, panoramas, magic lantern shows and song. Geoff Barker, Henry Beaufoy Merlin Showman and Photographer, 2018

- ^ Unknown, ‘Classified Advertising’, The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, (1 June 1853), 3.

- ^ Unknown, ‘Newcastle’, The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, (3 February 18573), 2.

- ^ Unknown, ‘Sydney’, Bell's Life in Victoria and Sporting Chronicle, (19 June 1858), 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Henry Beaufoy Merlin Showman and Photographer, 2018

- ^ Unknown, ‘Advertising’, Empire, (21 June 1858), 1.

- ^ for notes on the auctioneer Robert Muriel sharing the same last name being used by Merlin -see Henry Beaufoy Merlin Showman and Photographer, 2018

- ^ R. Bradshaw, ‘The Merlin of the South’, Australasian Drama Studies, no 7, Oct 1985, 121.

- ^ Richard Bradshaw, ‘Henry Beaufoy Merlin’ Archived 6 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2005

- ^ Unknown, ‘Parliamentary Intelligence’, The McIvor Times and Rodney Advertiser, (14 August 1863), 3.

- ^ Professor Pepper, The True Story of the Ghost, Cassell and Co., London, 1890, 4.

- ^ for more on the possible sources of Merlin's knowledge of the illusion and challenges to the patent see Henry Beaufoy Merlin Showman and Photographer, 2018

- ^ Unknown, ‘News and Notes’, The Star, (10 August 1863), 2.

- ^ Unknown, ‘The Ghost Again’, Mount Alexander Mail, (29 September 1863), 2.

- ^ Unknown, ‘Topics of the Day’, The South Australian Advertiser, (17 October 1863), 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b H Merlin, ‘Advertising’, The Kyneton Observer, (26 January 1865), 3.

- ^ Unknown, ‘New Insolvents’, The Age, (6 May 1865), 7.

- ^ for comments on the deficiency sought by creditors and Merlin's wealth see Henry Beaufoy Merlin Showman and Photographer, 2018

- ^ Although she was travelling under the name of Mrs Forster her husband had died in 1856. R. Bradshaw, ‘The Merlin of the South’, Australasian Drama Studies, no 7, Oct 1985, 106.

- ^ Unknown, ‘Ballarat District Exhibition’, The Ballarat Star, (3 September 1866), 4.

- ^ Unknown, ‘Landscape Photography’, Border Watch, (17 February 1869), 2.

- ^ ‘Fire’, Hamilton Spectator and Grange District Advertiser, (23 June 1869), 3.

- ^ On 16 September 1869 an advertisement for the American and Australasian Photographic Company records the sole main office as being 73 Little Collins Street. A second advertisement from 28 September adds a second city office at 4 Barrack Street Sydney. Unknown, ‘Advertising’, The Record, (16 September 1869), 7 and ‘Advertising’, Ovens and Murray Advertiser, (28 September 1869), 3.

- ^ For comments on this model and the employing other photographers including Charles Bayliss see Henry Beaufoy Merlin Showman and Photographer, 2018

- ^ Unknown, The Benalla Ensign and Farmer's and Squatter's Journal, (8 October 1869), 2.

- ^ ‘Advertising’, Ovens and Murray Advertiser, (25 September 1869), 2.

- ^ Merlin is the photographer mentioned in the advertisements but it is presumed that Charles Bayliss was also travelling with him. see Henry Beaufoy Merlin Showman and Photographer, 2018

- ^ ‘El Dorado’, Ovens and Murray Advertiser, (7 December 1869), 4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b ‘Extracts’, The Queanbeyan Age, (24 February 1870), 2.

- ^ ‘Advertising’, The Sydney Morning Herald, (17 October 1871), 1.

- ^ Although the party decided on 6 December to land at Island No. 6 Claremont Group as shallow waters would make the landing with all their scientific equipment at Cape Sidmouth too difficult. ‘The Eclipse Expedition’, Australian Town and Country Journal, (6 January 1872), 25.

- ^ Beaufoy Merlin, ‘The Eclipse Expedition’, Australian Town and Country Journal, (6 January 1872), 25.

- ^ Beaufoy Merlin, ‘The Eclipse Expedition’, Evening News, (2 January 1872), 3.

- ^ ‘Advertising’, The Sydney Morning Herald, (5 February 1872), 1.

- ^ ‘Local and General News’, Gympie Times and Mary River Mining Gazette, (24 January 1872), 2.

- ^ ‘Advertising’, Wagga Wagga Advertiser and Riverine Reporter, (20 January 1872), 3.

- ^ ‘Advertising’, The Sydney Morning Herald, (8 May 1872), 1.

- ^ Unknown, ‘Bathurst’, Freeman's Journal, (26 October 1872), 10.

- ^ Henry Beaufoy Merlin, Australian Showman and Photographer Archived 2 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine, State Library of New South Wales, 2018

- ^ Keast Burke in his 1953 article stated that when Merlin travelled to Sydney around 1869 Bayliss had been left in charge of his studio in Victoria. This may have possibly been the case but by early 1871 Bayliss was working for Merlin in Sydney. Burke also mentions that it was Holtermann that brought Bayliss back to Sydney and there is some merit in thinking this may have been the case if Bayliss had returned to Victoria sometime after Merlin left the business in February 1872. Confusingly, Keast Burke also published a correction in the Australian Photo Review, 1 July 1853, in which he states, ‘Contrary to first indication, it now appears that Charles Baylis did not remain behind in Melbourne for very long, or if at all. Fresh evidence has come to light showing that Bayliss accompanied Merlin to Gulgong and Hill End as his cameraman and photographed many of the sequences. In the face of this new evidence, it is only possible in a few instances to state with accuracy whether an exposure was made by one or the other photographer.’ Unfortunately, Burke does not cite the source of this new evidence and given contemporary newspapers only mention Merlin as the photographer it seems appropriate to assume this was the case until the ‘new evidence’ cited by Burke is found. Keast Burke, ‘Charles Bayliss’, Australian Photo Review, (1 July 1953) Vol. 60 No. 7, 396 and ‘Correction’, Australian Photo Review, (1 September 1953). Vol. 60 No. 9, 543.

- ^ ‘Metropolitan’, Empire, (4 May 1872), 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b ‘Photographs of Hill End and Hawkins’ Hill’, Evening News, (7 May 1872), 2

- ^ ‘Saturday, 16 November’, The Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser, (16 November 1872), 4

- ^ "Mr Bernard Otto Holtermann (1838–1885)". Former Members of the Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ The largest specimen of reef gold in the world, Hill End Archived 2 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine State Library of New South Wales, ON 4 Box 13 No [1]

- ^ ‘Hawkins’ Hill’, Australian Town and Country Journal, (18 May 1872), 16.

- ^ ‘Correspondence’, The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, (16 November 1872), 628.

- ^ Holtermann, ‘Biographical Note’, Holtermann Papers, State Library of New South Wales, ZML MSS 968 item 1

- ^ Beaufoy Merlin, ‘Advertising’, The Sydney Morning Herald, (3 January 1873), 1

- ^ ‘Intercolonial News’, The Queenslander, (18 January 1873), 9.

- ^ Clarke Street decorated for visit of Governor Sir Hercules Robinson, 11 March 1873, Hill End, State Library of New South Wales, ON 4 Box 9 No 18824

- ^ Unknown, ‘From Our Correspondents’, Empire, (5 April 1873), 2.

- ^ The article also reproduced a wood-cut view of Summer Street, Bathurst, from a negative still held by the State Library of New South Wales. Merlin [attrib.], ‘Rough Notes by the Photographic Artist of Holtermann's Exhibition’, Australian Town and Country Journal, (5 July 1873), 19.

- ^ Unknown, ‘Notes of the Week’, The Sydney Morning Herald, (2 August 1873), 5.

- ^ Unknown, ‘Holtermann's Exhibition’, Empire, (23 July 1873), 2.

- ^ Unknown, ‘Social’, Empire, (9 August 1873), 5.

- ^ Unknown, ‘Exposition’, Australian Town and Country Journal, (27 September 1873), 10.

- ^ Geoff Barker Henry Beaufoy Merlin Showman and Photographer, 2018

- ^ Merlin, ‘Recent Discoveries in New Guinea’, Empire, (14 August 1873), 4.

- ^ Merlin, "The French Ironclad", Australian Town and Country Journal, (23 August 1873), 242.

- ^ Merlin, ‘From Orange to Dubbo’, Australian Town and Country Journal, (27 September 1873), 10.

- ^ Richard Bradshaw, ‘Henry Beaufoy Merlin’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2005, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/merlin-henry-beaufoy-13096/text23693 Archived 6 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Unknown, ‘The Death of Mr. Merlin’, Evening News, (29 September 1873), 2.

- ^ ’Unknown, ‘The Death of Mr. Merlin’, Evening News, (29 September 1873), 2.

- ^ "Hill End and Tambaroora". Australian Town and Country Journal. VIII (196). New South Wales, Australia. 4 October 1873. p. 9 – via National Library of Australia. Merlin Obituary

- ^ "Old Photographs Tell Story Of Gold Rush". The Sydney Morning Herald (35, 940). New South Wales, Australia. 28 February 1953. p. 2 – via National Library of Australia. Discovery of Merlin and Bayliss Photographs.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holtermann & Burke 1973, p. 36-47.

- ^ "THE VOLUNTEER ENCAMPMENT". The Empire (8092). New South Wales, Australia. 5 May 1874. p. 2 – via National Library of Australia. Merlin's Mother ill and in financial distress.

- ^ The UNESCO Memory of the World Program, The Australian Register, The Holteramnn Collection Archived 28 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Beaufoy Merlin. |

- Richard Bradshaw, 'Merlin, Henry Beaufoy (1830–1873)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 2005. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- Holtermann, Bernhardt Otto; Burke, Keast (1973). Gold and silver : photographs of Australian goldfields from the Holtermann Collection. Ringwood, Vic. Harmondsworth, Eng.: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-003752-4.

- The UNESCO Memory of the World Program, The Australian Register, The Holteramnn Collection

- Holtermann Collection, blog post, State Library of New South Wales.

- The Holtermann Photographic Collection, story post, State Library of New South Wales.

- Holtermann Collection, State Library of New South Wales.

- Alan, Davies, Holtermann and the A&A Photographic Company, blog post, State Library of New South Wales, 2010.

- Holtermann on Holterman, 18-page manuscript about Bernhardt Otto Holtermann, c.1975, blog post, State Library of New South Wales, 2011.

- Geoff Barker Henry Beaufoy Merlin: Australian showman and photographer, blog post, State Library of New South Wales, 2018.

- "AUSTRALIAN PHOTOGRAPHS". The Argus (9, 163). Victoria, Australia. 27 October 1875. p. 6 – via National Library of Australia.

- The Argus, Wednesday 27 October 1875. Largest Photographic Views in the World. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- "PERSEVERANCE REWARDED.—MR. J. O. HOLTERMAN". The Empire (6429). New South Wales, Australia. 13 November 1872. p. 4 – via National Library of Australia.

- Empire, Wednesday 13 November 1872. Article by Beaufoy Merlin on B. O. Holtermann. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- "Intercolonial News". The Queenslander. VII (363). Queensland, Australia. 18 January 1873. p. 9 – via National Library of Australia.

- The Queenslander Saturday 18 January 1873. Proposed Inter-Colonial Exhibition. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- "SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 1872". The Argus (8, 009). Victoria, Australia. 10 February 1872. p. 5 – via National Library of Australia.

- The Argus Saturday 10 February 1872. Merlin accompanies "Australian Eclipse" Exhibition. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- Australian photographers

- 1830s births

- 1873 deaths

- English emigrants to colonial Australia

- People from Wells-next-the-Sea

- Australian gold rushes