New South Wales

New South Wales | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

State | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname(s): The First State The Premier State | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto(s): Orta Recens Quam Pura Nites (Newly Risen, How Brightly You Shine) | |||||||||||||||||||||

Location of New South Wales in Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates: 32°S 147°E / 32°S 147°ECoordinates: 32°S 147°E / 32°S 147°E | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Country | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Crown colony as Colony of New South Wales | 26 January 1788 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Responsible government | 6 June 1856 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Federation | 1 January 1901 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Australia Act | 3 March 1986 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Sydney | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Largest city | Sydney | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||||||||||

| • Type | Constitutional monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • Body | Government of New South Wales | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • Governor | Margaret Beazley | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • Premier | Gladys Berejiklian (Liberal) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament of New South Wales

Legislative Council (42 seats) Legislative Assembly (93 seats) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Judiciary |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Federal representation | Parliament of Australia

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | 809,952 km2 (312,724 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • Land | 801,150 km2 (309,330 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • Water | 8,802 km2 (3,398 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Area rank | 5th | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Highest elevation (Mount Kosciuszko) | 2,228 m (7,310 ft) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Population (September 2020)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| • Total | 8,166,369 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • Rank | 1st | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • Density | 10/km2 (26/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • Density rank | 3rd | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | New South Welshman[2][3] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC+10 (AEST) UTC+11 (AEDT) UTC+9:30 (ACST) (Broken Hill) UTC+10:30 (ACDT) (Broken Hill) UTC+10:30 (LHST) (Lord Howe Island) UTC+11:00 (LHDT) (Lord Howe Island) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal code | NSW | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | AU-NSW | ||||||||||||||||||||

| GSP year | 2019–20 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| GSP ($A million) | $624,923[4] (1st) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| GSP per capita | $76,876 (4th) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates[7] Emblems[8] | |||||||||||||||||||||

New South Wales (abbreviated as NSW) is a state on the east coast of Australia. It borders three other states, Queensland to the north, Victoria to the south, and South Australia to the west. Its coast borders the Coral and Tasman Seas to the east. The Australian Capital Territory is an enclave within the state. New South Wales' state capital is Sydney, which is also Australia's most populous city. In June 2020, the population of New South Wales was over 8.1 million,[1] making it Australia's most populous state. Just under two-thirds of the state's population, 5.3 million, live in the Greater Sydney area.[9] The demonym for inhabitants of New South Wales is New South Welshmen.[2][3]

The Colony of New South Wales was founded as a British penal colony in 1788. It originally comprised more than half of the Australian mainland with its western boundary set at 129th meridian east in 1825. The colony then also included the island territories of Van Diemen's Land, Lord Howe Island, and Norfolk Island. During the 19th century, most of the colony's area was detached to form separate British colonies that eventually became the various states and territories of Australia. However, the Swan River Colony was never administered as part of New South Wales.

Lord Howe Island remains part of New South Wales, while Norfolk Island has become a federal territory, as have the areas now known as the Australian Capital Territory and the Jervis Bay Territory.

History[]

Aboriginal Australians[]

The original inhabitants of New South Wales were the Aboriginal tribes who arrived in Australia about 40,000 to 60,000 years ago. Before European settlement there were an estimated 250,000 Aboriginal people in the region.[10]

The Wodi wodi people are the original custodians of the Illawarra region of South Sydney.[11] Speaking a variant of the Dharawal language, the Wodi Wodi peoples lived across a large stretch of land which was roughly surrounded by what is now known as Campbelltown, Shoalhaven River and Moss Vale.[11]

The Bundjalung people are the original custodians of parts of the northern coastal areas.[12]

There are other Aboriginal peoples whose traditional lands are within what is now New South Wales, including the Wiradjiri, Gamilaray, Yuin, Ngarigo, Gweagal, and Ngiyampaa peoples.

1788 British settlement[]

In 1770 Lieutenant James Cook charted the unmapped eastern coast of the continent of New Holland, now Australia, and claimed the entire coastline that he had just explored as British territory without having gained the consent of the Indigenous inhabitants.[13] Cook first named the land New Wales which was later amended to New South Wales (NSW).[14]

In January 1788 Arthur Phillip arrived in Botany Bay with the First Fleet of 11 vessels, which carried over a thousand settlers, including 736 convicts.[15] A few days after arrival at Botany Bay, the fleet moved to the more suitable Port Jackson, where Phillip established a settlement at the place he named Sydney Cove (in honour of the Secretary of State, Lord Sydney) on 26 January 1788.[16] This date later became Australia's national day, Australia Day. The colony was formally proclaimed by Governor Phillip on 7 February 1788 at Sydney. Phillip, as Governor of New South Wales, exercised nominal authority over all of Australia east of the 135th meridian east between the latitudes of 10°37'S and 43°39'S, an area which includes modern New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria and Tasmania.[17] He remained as governor until 1792.[18]

The settlement was initially planned to be a self-sufficient penal colony based on subsistence agriculture. Trade and ship building were banned in order to keep the convicts isolated. However, after the departure of governor Phillip, the colony's military officers began acquiring land and importing consumer goods obtained from visiting ships. Former convicts also farmed land granted to them and engaged in trade. Farms spread to the more fertile lands surrounding Paramatta, Windsor and Camden, and by 1803 the colony was self-sufficient in grain. Boat building developed in order to make travel easier and exploit the marine resources of the coastal settlements. Sealing and whaling became important industries.[19]

In March 1804, several hundred United Irish exiles in the Castle Hill area (now a suburb of Sydney) conspired to seize control of the colony and to capture ships for a return to Ireland.[20] Poorly armed, and with their leader Philip Cunningham captured,[21] the main body of insurgents were routed in an encounter loyalists--recalling the decisive rebel defeat in Ireland in 1798--celebrated as the Second Battle of Vinegar Hill. Fifteen were killed and nine executed.[22]

Lachlan Macquarie (governor 1810-1821) commissioned the construction of roads, wharves, churches and public buildings, sent explorers out from Sydney and employed a planner to design the street layout of Sydney.[23] A road across the Blue Mountains was completed in 1815, opening the way for large scale farming and grazing in the lightly-wooded pastures west of the Great Dividing Range.[24]

In 1825 Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) became a separate colony and the western border of New South Wales was extended to the 129th meridian east (now the West Australian border).[25]

From the 1820s squatters increasingly established unauthorised cattle and sheep runs beyond the official limits of the settled colony. In 1836 an annual licence was introduced in an attempt to control the pastoral industry, but booming wool prices and the high cost of land in the settled areas encouraged further squatting. The expansion of the pastoral industry led to violent episodes of conflict between settlers and traditional Aboriginal landowners, such as the Myall Creek massacre of 1838.[26] By 1844 wool accounted for half of the colony's exports and by 1850 most of the eastern third of New South Wales was controlled by fewer than 2,000 pastoralists.[27]

The transportation of convicts to New South Wales ended in 1840, and in 1842 a Legislative Council was introduced, with two-thirds of its members elected and one-third appointed by the governor. Former convicts were granted the vote, but a property qualification meant that only one in five adult males were enfranchised.[28]

By 1850 the settler population of New South Wales had grown to 180,000, not including the 70,000 living in the area which became the separate colony of Victoria in 1851.[29]

1850s to 1890s[]

In 1856 New South Wales achieved responsible government with the introduction of a bicameral parliament comprising a directly elected Legislative Assembly and a nominated Legislative Council. The property qualification for voters had been reduced in 1851, and by 1856 95 per cent of adult males in Sydney, and 55 per cent in the colony as a whole, were eligible to vote. Full adult male suffrage was introduced in 1858. In 1859 Queensland became a separate colony.[30]

In 1861 the NSW parliament legislated land reforms intended to encourage family farms and mixed farming and grazing ventures. The amount of land under cultivation subsequently grew from 246,000 acres in 1861 to 800,000 acres in the 1880s. Wool production also continued to grow, and by the 1880s New South Wales produced almost half of Australia's wool. Coal had been discovered in the early years of settlement and gold in 1851, and by the 1890s wool, gold and coal were the main exports of the colony.[31]

The NSW economy also became more diversified. From the 1860s, New South Wales had more people employed in manufacturing than any other Australian colony. The NSW government also invested heavily in infrastructure such as railways, telegraph, roads, ports, water and sewerage. By 1889 it was possibly to travel by train from Brisbane to Adelaide via Sydney and Melbourne. The extension of the rail network inland also encouraged regional industries and the development of the wheat belt.[32]

In the 1880s trade unions grew and were extended to lower skilled workers. In 1890 a strike in the shipping industry spread to wharves, railways, mines and shearing sheds. The defeat of the strike was one of the factors leading the Trades and Labor Council to form a political party. The Labor Electoral League won a quarter of seats in the NSW elections of 1891 and held the balance of power between the Free Trade Party and the Protectionist Party.[33][34]

1901 Federation of Australia[]

A Federal Council of Australasia was formed in 1885 but New South Wales declined to join. A major obstacle to the federation of the Australian colonies was the protectionist policies of Victoria which conflicted with the free trade policies dominant in New South Wales. Nevertheless, the NSW premier Henry Parkes was a strong advocate of federation and his Tenterfield Oration in 1889 was pivotal in gathering support for the cause. Parkes also struck a deal with Edmund Barton, leader of the NSW Protectionist Party, whereby they would work together for federation and leave the question of a protective tariff for a future Australian government to decide.[35]

In early 1893 the first citizens' Federation League was established in the Riverina region of New South Wales and many other leagues were soon formed in the colony. The leagues organised a conference in Corowa in July 1893 which developed a plan for federation. The new NSW premier, George Reid, endorsed the "Corowa plan" and in 1895 convinced the majority of other premiers to adopt it. A constitutional convention held sessions in 1897 and 1898 which resulted in a proposed constitution for a Commonwealth of federated states. However, a referendum on the constitution failed to gain the required majority in New South Wales after that colony's Labor party campaigned against it and premier Reid gave it such qualified support that he earned the nickname "yes-no Reid".[36]

The premiers of the other colonies agreed to a number of concessions to New South Wales (particularly that the future Commonwealth capital would be located in NSW), and in 1899 further referendums were held in all the colonies except Western Australia. All resulted in yes votes, with the yes vote in New South Wales meeting the required majority. The imperial parliament passed the necessary enabling legislation in 1900 and Western Australia subsequently voted to join the new federation. The Commonwealth of Australia was inaugurated on 1 January 1901, and Barton was sworn in as Australia's first prime minister.[37]

1901 to 1945[]

The first post-federation NSW governments were Progressive or Liberal Reform and implemented a range of social reforms with Labor support. Women won the right to vote in NSW elections in 1902, but were ineligible to stand for parliament until 1918. Labor increased its parliamentary representation in every election from 1904 before coming to power in 1910 with a majority of one seat.[38][39]

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 saw more NSW volunteers for service than the federal authorities could handle, leading to unrest in camps as recruits waited for transfer overseas. In 1916 NSW premier William Holman and a number of his supporters were expelled from the Labor party over their support for military conscription. Holman subsequently formed a Nationalist government which remained in power until 1920. Despite a huge victory for Holman's pro-conscription Nationalists in the elections of March 1917, a second referendum on conscription held in December that year was defeated in New South Wales and nationally.[40]

Following the war, NSW governments embarked on large public works programs including road building, the extension and electrification of the rail network and construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The works were largely funded by loans from London, leading to a debt crisis after the onset of the Great Depression in 1929. New South Wales was hit harder by the depression than other states, and by 1932 one third of union members in the state were unemployed, compared with 20 per cent nationally.[41]

Labor won the November 1930 NSW elections and Jack Lang became premier for the second time. In 1931 Lang proposed a plan to deal with the depression which included a suspension of interest payments to British creditors, diverting the money to unemployment relief. The Commonwealth and state premiers rejected the plan and later that year Lang's supporters in the Commonwealth parliament brought down James Scullin's federal Labor government. The NSW Lang government subsequently defaulted on overseas interest payments and was dismissed from office in May 1932 by the governor, Sir Phillip Game.[42][43]

The following elections were won comfortably by the United Australia Party in coalition with the Country Party. Bertram Stevens became premier, remaining in office until 1939, when he was replaced by Alexander Mair.[44]

A contemporary study by sociologist A. P. Elkin found that the population of New South Wales responded to the outbreak of war in 1939 with pessimism and apathy. This changed with the threat of invasion by Japan, which entered the war in December 1941. In May 1942 three Japanese midget submarines entered Sydney harbour and sank a naval ship, killing 29 men aboard. The following month Sydney and Newcastle were shelled by Japanese warships. American troops began arriving in the state in large numbers. Manufacturing, steelmaking, shipbuilding and rail transport all grew with the war effort and unemployment virtually disappeared.[45]

A Labor government led by William McKell was elected in May 1941. The McKell government benefited from full employment, budget surpluses and a co-operative relationship with John Curtin's federal Labor government. McKell became the first Labor leader to serve a full term and to be re-elected for a second. The Labor party was to govern New South Wales until 1965.[46]

Post-war period[]

The Labor government introduced two-weeks paid leave for most NSW workers in 1944, and the 40 hour working week was implemented by 1947. The post-war economic boom brought full employment and rising living standards, and the government engaged in large spending programs on housing, dams, electricity generation and other infrastructure. In 1954 the government announced a plan for the construction of an opera house on Bennelong Point. The design competition was won by Jørn Utzon. Controversy over the cost of the Sydney Opera House and construction delays became a political issue and was a factor in the eventual defeat of Labor in 1965 by the conservative Liberal Party and Country Party coalition led by Robert Askin.[47]

The Askin government promoted private development, law and order issues and greater state support for non-government schools. However, Askin, a former bookmaker, became increasingly associated with illegal bookmaking, gambling and police corruption.[48]

In the late 1960s a secessionist movement in the New England region of the state led to a 1967 referendum on the issue which was narrowly defeated. The new state would have consisted of much of northern NSW including Newcastle.[49]

Askin's resignation in 1975 was followed by a number of short lived premierships by Liberal Party leaders. When a general election came in 1976 the ALP under Neville Wran came to power.[50] Wran was able to transform this narrow one seat victory into landslide wins (known as Wranslides) in 1978 and 1981.[51]

After winning a comfortable though reduced majority in 1984, Wran resigned as premier and left parliament. His replacement Barrie Unsworth struggled to emerge from Wran's shadow and lost a 1988 election against a resurgent Liberal Party led by Nick Greiner. The Greiner government embarked on an efficiency program involving public sector cost-cutting, the corporatisation of government agencies and the privatisation of some government services. An Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) was created.[52] Greiner called a snap election in 1991 which the Liberals were expected to win. However the ALP polled extremely well and the Liberals lost their majority and needed the support of independents to retain power.

In 1992 Greiner was investigated by ICAC for possible corruption over the offer of a public service position to a former Liberal MP. Greiner resigned but was later cleared of corruption. His replacement as Liberal leader and Premier was John Fahey, whose government narrowly lost the 1995 election to the ALP under Bob Carr, who was to become the longest serving premier of the state.[53]

The Carr government (1995-2005) largely continued its predecessors' focus on the efficient delivery of government services such as health, education, transport and electricity. There was an increasing emphasis on public-private partnerships to deliver infrastructure such as freeways, tunnels and rail links. The Carr government gained popularity for its successful organisation of international events, especially the 2000 Sydney Olympics, but Carr himself was critical of the federal government over its high immigration intake, arguing that a disproportionate number of new migrants were settling in Sydney, putting undue pressure on state infrastructure.[54]

Carr unexpectedly resigned from office in 2005 and was replaced by Morris Iemma, who remained premier after being re-elected in the March 2007 state election, until he was replaced by Nathan Rees in September 2008.[55] Rees was subsequently replaced by Kristina Keneally in December 2009, who became the first female premier of New South Wales.[56] Keneally's government was defeated at the 2011 state election and Barry O'Farrell became Premier on 28 March. On 17 April 2014 O'Farrell stood down as Premier after misleading an ICAC investigation concerning a gift of a bottle of wine.[57] The Liberal Party then elected Treasurer Mike Baird as party leader and Premier. Baird resigned as Premier on 23 January 2017, and was replaced by Gladys Berejiklian.[58]

Geography and ecology[]

New South Wales is bordered on the north by Queensland, on the west by South Australia, on the south by Victoria and on the east by the Coral and Tasman Seas. The Australian Capital Territory and the Jervis Bay Territory form a separately administered entity that is bordered entirely by New South Wales. The state can be divided geographically into four areas. New South Wales's three largest cities, Sydney, Newcastle and Wollongong, lie near the centre of a narrow coastal strip extending from cool temperate areas on the far south coast to subtropical areas near the Queensland border.

The Illawarra region is centred on the city of Wollongong, with the Shoalhaven, Eurobodalla and the Sapphire Coast to the south. The Central Coast lies between Sydney and Newcastle, with the Mid North Coast and Northern Rivers regions reaching northwards to the Queensland border. Tourism is important to the economies of coastal towns such as Coffs Harbour, Lismore, Nowra and Port Macquarie, but the region also produces seafood, beef, dairy, fruit, sugar cane and timber.

The Great Dividing Range extends from Victoria in the south through New South Wales to Queensland, parallel to the narrow coastal plain. This area includes the Snowy Mountains, the Northern, Central and Southern Tablelands, the Southern Highlands and the South West Slopes. Whilst not particularly steep, many peaks of the range rise above 1,000 metres (3,281 ft), with the highest Mount Kosciuszko at 2,229 m (7,313 ft). Skiing in Australia began in this region at Kiandra around 1861. The relatively short ski season underwrites the tourist industry in the Snowy Mountains. Agriculture, particularly the wool industry, is important throughout the highlands. Major centres include Armidale, Bathurst, Bowral, Goulburn, Inverell, Orange, Queanbeyan and Tamworth.

There are numerous forests in New South Wales, with such tree species as Red Gum Eucalyptus and Crow Ash (Flindersia australis), being represented.[59] Forest floors have a diverse set of understory shrubs and fungi. One of the widespread fungi is Witch's Butter (Tremella mesenterica).[60]

The western slopes and plains fill a significant portion of the state's area and have a much sparser population than areas nearer the coast. Agriculture is central to the economy of the western slopes, particularly the Riverina region and Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area in the state's south-west. Regional cities such as Albury, Dubbo, Griffith and Wagga Wagga and towns such as Deniliquin, Leeton and Parkes exist primarily to service these agricultural regions. The western slopes descend slowly to the western plains that comprise almost two-thirds of the state and are largely arid or semi-arid. The mining town of Broken Hill is the largest centre in this area.[61]

One possible definition of the centre for New South Wales is located 33 kilometres (21 mi) west-north-west of Tottenham.[62]

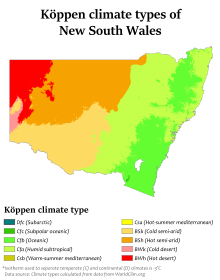

Climate[]

A little more than half of the state has an arid to semi arid climate, where the rainfall averages from 150 to 500 millimetres (5.9 to 19.7 in) a year throughout most of this climate zone. Summer temperatures can be very hot, while winter nights can be quite cold in this region. Rainfall varies throughout the state. The far north-west receives the least, less than 180 mm (7 in) annually, while the east receives between 700 to 1,400 mm (28 to 55 in) of rain.[63]

The climate along the flat, coastal plain east of the range varies from oceanic in the south to humid subtropical in the northern half of the state, right above Wollongong. Rainfall is highest in this area; however, it still varies from around 800 millimetres (31 in) to as high as 3,000 millimetres (120 in) in the wettest areas, for example Dorrigo. In the state's south, on the westward side of the Great Dividing Range, rainfall is heaviest in winter due to cold fronts which move across southern Australia, while in the north, around Lismore, rain is heaviest in summer from tropical systems and occasionally even cyclones.[63] During late winter, the coastal plain is relatively dry due to Foehn winds that originate from the Great Dividing Range;[64] the mountain range block the moist, westerly cold fronts that arrive from the Southern Ocean, whereby providing generally clear conditions on the leeward side.[65][66]

The climate in the southern half of the state is generally warm to hot in summer and cool in the winter. The seasons are more defined in the southern half of the state, especially as one moves inland towards South West Slopes, Central West and the Riverina region. The climate in the northeast region of the state, or the North Coast, bordering Queensland, is hot and humid in the summer and mild in winter. The Northern Tablelands, which are also on the North coast, have relatively mild summers and cold winters, due to their high elevation on the Great Dividing Range.

Peaks along the Great Dividing Range vary from 500 metres (1,640 ft) to over 2,000 metres (6,562 ft) above sea level. Temperatures can be cool to cold in winter with frequent frosts and snowfall, and are rarely hot in summer due to the elevation. Lithgow has a climate typical of the range, as do the regional cities of Orange, Cooma, Oberon and Armidale. Such places fall within the subtropical highland (Cwb) variety. Rainfall is moderate in this area, ranging from 600 to 800 mm (24 to 31 in).

Snowfall is common in the higher parts of the range, sometimes occurring as far north as the Queensland border. On the highest peaks of the Snowy Mountains, the climate can be subpolar oceanic and even alpine on the higher peaks with very cold temperatures and heavy snow. The Blue Mountains, Southern Tablelands and Central Tablelands, which are situated on the Great Dividing Range, have mild to warm summers and cold winters, although not as severe as those in the Snowy Mountains.[63]

The highest maximum temperature recorded was 49.7 °C (121 °F) at Menindee in the west of the state on 10 January 1939. The lowest minimum temperature was −23 °C (−9 °F) at Charlotte Pass in the Snowy Mountains on 29 June 1994. This is also the lowest temperature recorded in the whole of Australia excluding the Antarctic Territory.[67]

| hideClimate data for New South Wales | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 49.7 (121.5) |

48.5 (119.3) |

45.0 (113.0) |

40.0 (104.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.7 (89.1) |

37.8 (100.0) |

39.6 (103.3) |

43.9 (111.0) |

46.8 (116.2) |

48.9 (120.0) |

49.7 (121.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.6 (21.9) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

−19.6 (−3.3) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−16.7 (1.9) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−23.0 (−9.4) |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[68] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[]

The estimated population of New South Wales at the end of September 2018 was 8,223,700 people, representing approximately 32.96% of nationwide population.[1]

In June 2017 Sydney was home to almost two-thirds (65.3%) of the NSW population.[9]

Cities and towns[]

| NSW rank | Statistical Area Level 2 | Population (30 June 2014)[69] |

10-year growth rate | Population density (people/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Greater Sydney | 4,940,628 | 15.7 | 397.4 |

| 2 | Newcastle and Lake Macquarie | 368,131 | 9.0 | 423.1 |

| 3 | Illawarra | 296,845 | 9.3 | 192.9 |

| 4 | Hunter Valley excluding Newcastle | 264,087 | 16.2 | 12.3 |

| 5 | Richmond Tweed | 242,116 | 8.9 | 23.6 |

| 6 | Capital region | 220,944 | 10.9 | 4.3 |

| 7 | Mid North Coast | 212,787 | 9.2 | 11.3 |

| 8 | Central West | 209,850 | 7.9 | 3.0 |

| 9 | New England and North West | 186,262 | 5.3 | 1.9 |

| 10 | Riverina | 158,144 | 4.7 | 2.8 |

| 11 | Southern Highlands and Shoalhaven | 146,388 | 10.4 | 21.8 |

| 12 | Coffs Harbour-Grafton | 136,418 | 7.6 | 10.3 |

| 13 | Far West and Orana | 119,742 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| 14 | Murray | 116,130 | 4.0 | 1.2 |

| New South Wales | 7,518,472 | 10.4 | 13.0 |

| NSW rank | Significant Urban Area | Population (30 June 2018)[70] |

Australia rank | 10-year growth rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sydney | 4,835,206 | 1 | 19.3 |

| 2 | Newcastle – Maitland | 486,704 | 7 | 11.3 |

| 3 | Central Coast | 333,627 | 9 | 19.5 |

| 4 | Wollongong | 302,739 | 11 | 11.2 |

| 5 | Albury - Wodonga | 93,603 | 20 | 14.9 |

| 6 | Coffs Harbour | 71,822 | 25 | 11.8 |

| 7 | Wagga Wagga | 56,442 | 28 | 6.7 |

| 8 | Port Macquarie | 47,973 | 33 | 15.6 |

| 9 | Tamworth | 42,872 | 34 | 10.9 |

| 10 | Orange | 40,493 | 36 | 12.9 |

| 11 | Bowral – Mittagong | 39,887 | 37 | 13.5 |

| 12 | Dubbo | 38,392 | 39 | 12.2 |

| 13 | Nowra – Bomaderry | 37,420 | 42 | 14 |

| 14 | Bathurst | 33,801 | 43 | 15.0 |

| 15 | Lismore | 28,720 | 49 | -0.9 |

| 16 | 28,051 | 50 | 13.2 | |

| 17 | Taree | 26,448 | 55 | 2.3 |

| 18 | Ballina | 26,381 | 55 | 10.1 |

| 19 | Morisset – Cooranbong | 25,309 | 57 | 15.1 |

| 20 | Armidale | 24,504 | 58 | 7.0 |

| 21 | Goulburn | 23,835 | 59 | 12 |

| 22 | Forster – Tuncurry | 21,159 | 65 | 7.3 |

| 23 | Griffith | 20,251 | 66 | 11.5 |

| 24 | St Georges Basin – Sanctuary Point | 19,251 | 68 | 19.1 |

| 25 | Grafton | 19,078 | 69 | 3.5 |

| 26 | Camden Haven | 17,835 | 73 | 12.4 |

| 27 | Broken Hill | 17,734 | 74 | −9.5 |

| 28 | Batemans Bay | 16,485 | 78 | 4.4 |

| 29 | Singleton | 16,346 | 79 | -0.6 |

| 30 | Ulladulla | 16,213 | 81 | 11.8 |

| 31 | Kempsey | 15,309 | 84 | 5.8 |

| 32 | Lithgow | 12,973 | 93 | 4.8 |

| 33 | Mudgee | 12,410 | 95 | 21.5 |

| 34 | Muswellbrook | 12,364 | 96 | 5.0 |

| 35 | Parkes | 11,224 | 98 | 2.1 |

| New South Wales | 7,480,228 | N/A | 17.6 | |

Ancestry and immigration[]

| Birthplace[N 1] | Population |

|---|---|

| Australia | 4,899,090 |

| China | 234,508 |

| England | 226,564 |

| India | 143,459 |

| New Zealand | 117,136 |

| Philippines | 86,749 |

| Vietnam | 84,130 |

| Lebanon | 57,381 |

| South Korea | 51,816 |

| Italy | 49,476 |

| South Africa | 43,058 |

| Hong Kong | 42,347 |

At the 2016 census, the most commonly nominated ancestries were:[N 2][72][71]

At the 2016 census, there were 2,581,138 people living in New South Wales that were born overseas, accounting for 34.5% of the population. Only 45.4% of the population had both parents born in Australia.[72][71]

2.9% of the population, or 216,176 people, identified as Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders) in 2016.[N 5][72][71]

Language[]

26.5% of people in New South Wales speak a language other than English at home with Mandarin (3.2%), Arabic (2.7%), Cantonese (1.9%), Vietnamese (1.4%) and Greek (1.1%) the most widely spoken.[72][71]

Religion[]

In the 2016 census, the most commonly reported religions and Christian denominations were Roman Catholicism (24.7%), Anglicanism (15.5%) and Islam (3.6%). 25.1% of the population described themselves as having no religion.[74]

Government[]

Executive authority is vested in the Governor of New South Wales, who represents and is appointed by Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia. The current Governor is Margaret Beazley. The Governor commissions as Premier the leader of the parliamentary political party that can command a simple majority of votes in the Legislative Assembly. The Premier then recommends the appointment of other Members of the two Houses to the Ministry, under the principle of responsible or Westminster government. As in other Westminster systems, there is no constitutional requirement in NSW for the Government to be formed from the Parliament—merely convention. The Premier is Gladys Berejiklian of the Liberal Party.[56]

Constitution[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The form of the Government of New South Wales is prescribed in its Constitution, dating from 1856 and currently the Constitution Act 1902 (NSW).[75] Since 1901 New South Wales has been a state of the Commonwealth of Australia, and the Australian Constitution regulates its relationship with the Commonwealth.

In 2006, the Constitution Amendment Pledge of Loyalty Act 2006 No 6,[76] was enacted to amend the NSW Constitution Act 1902 to require Members of the New South Wales Parliament and its Ministers to take a pledge of loyalty to Australia and to the people of New South Wales instead of swearing allegiance to Elizabeth II her heirs and successors, and to revise the oaths taken by Executive Councillors. The Pledge of Loyalty Act was officially assented to by the Queen on 3 April 2006. The option to swear allegiance to the Queen was restored as an alternative option in June 2012.

Under the Australian Constitution, New South Wales ceded certain legislative and judicial powers to the Commonwealth, but retained independence in all other areas. The New South Wales Constitution says: "The Legislature shall, subject to the provisions of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, have power to make laws for the peace, welfare, and good government of New South Wales in all cases whatsoever".[77]

Parliament[]

The first "responsible" self-government of New South Wales was formed on 6 June 1856 with Sir Stuart Alexander Donaldson appointed by Governor Sir William Denison as its first Colonial Secretary which in those days accounted also as the Premier.[78] The Parliament of New South Wales is composed of the Sovereign and two houses: the Legislative Assembly (lower house), and the Legislative Council (upper house). Elections are held every four years on the fourth Saturday of March, the most recent being on 23 March 2019. At each election one member is elected to the Legislative Assembly from each of 93 electoral districts and half of the 42 members of the Legislative Council are elected by a statewide electorate.

Local government[]

New South Wales is divided into 128 local government areas. There is also the Unincorporated Far West Region which is not part of any local government area, in the sparsely inhabited Far West, and Lord Howe Island, which is also unincorporated but self-governed by the Lord Howe Island Board.

Emergency services[]

New South Wales is policed by the New South Wales Police Force, a statutory authority. Established in 1862, the New South Wales Police Force investigates Summary and Indictable offences throughout the State of New South Wales. The state has two fire services: the volunteer based New South Wales Rural Fire Service, which is responsible for the majority of the state, and the Fire and Rescue NSW, a government agency responsible for protecting urban areas. There is some overlap in due to suburbanisation. Ambulance services are provided through the New South Wales Ambulance. Rescue services (i.e. vertical, road crash, confinement) are a joint effort by all emergency services, with Ambulance Rescue, Police Rescue Squad and Fire Rescue Units contributing. Volunteer rescue organisations include Marine Rescue New South Wales, State Emergency Service (SES), Surf Life Saving New South Wales and Volunteer Rescue Association (VRA).

Education[]

Primary and Secondary[]

The NSW school system comprises a kindergarten to year 12 system with primary schooling up to year 6 and secondary schooling between years 7 and 12. Schooling is compulsory from before 6 years old until the age of 17 (unless Year 10 is completed earlier).[79] Between 1990 and 2010, schooling was only compulsory in NSW until age 15.[80]

Primary and secondary schools include government and non-government schools. Government schools are further classified as comprehensive and selective schools. Non-government schools include Catholic schools, other denominational schools, and non-denominational independent schools.

Typically, a primary school provides education from kindergarten level to year 6. A secondary school, usually called a "high school", provides education from years 7 to 12. Secondary colleges are secondary schools which only cater for years 11 and 12.

The NSW Education Standards Authority classifies the 13 years of primary and secondary schooling into six stages, beginning with Early Stage 1 (Kindergarten) and ending with Stage 6 (years 11 and 12).[81][82]

Record of School Achievement[]

A Record of School Achievement (RoSA) is awarded by the NSW Education Standards Authority to students who have completed at least Year 10 but leave school without completing the Higher School Certificate.[83] The RoSA was introduced in 2012 to replace the former School Certificate.

Higher School Certificate[]

The Higher School Certificate (HSC) is the usual Year 12 leaving certificate in NSW. Most students complete the HSC prior to entering the workforce or going on to study at university or TAFE (although the HSC itself can be completed at TAFE). The HSC must be completed for a student to get an Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (formerly Universities Admission Index), which determines the student's rank against fellow students who completed the Higher School Certificate.

Tertiary[]

Eleven universities primarily operate in New South Wales. Sydney is home to Australia's first university, the University of Sydney founded in 1850. Other universities include the University of New South Wales, Macquarie University, University of Technology, Sydney and Western Sydney University. The Australian Catholic University has two of its six campuses in Sydney, and the private University of Notre Dame Australia also operates a secondary campus in the city.

Outside Sydney, the leading universities are the University of Newcastle and the University of Wollongong. Armidale is home to the University of New England, and Charles Sturt University. Southern Cross University has campuses spread across cities in the state's north coast.

The public universities are state government agencies, however they are largely regulated by the federal government, which also administers their public funding. Admission to NSW universities is arranged together with universities in the Australian Capital Territory by another government agency, the Universities Admission Centre.

Primarily vocational training is provided up the level of advanced diplomas is provided by the state government's ten Technical and Further Education (TAFE) institutes. These institutes run courses in more than130 campuses throughout the state.

Economy[]

Since the 1970s, New South Wales has undergone an increasingly rapid economic and social transformation.[citation needed] Old industries such as steel and shipbuilding have largely disappeared; although agriculture remains important, its share of the state's income is smaller than ever before.[citation needed]

New industries including information technology and financial services are largely centred in Sydney and have risen to take their place, with many companies having their Australian headquarters in Sydney CBD.[citation needed] In addition, the Macquarie Park area of Sydney has attracted the Australian headquarters of many information technology firms.

Coal and related products are the state's biggest export. Its value to the state's economy is over A$5 billion, accounting for about 19% of all exports from NSW.[84]

Tourism has also become important, with Sydney as its centre, also stimulating growth on the North Coast, around Coffs Harbour and Byron Bay.[citation needed] Tourism is worth over $25.1 billion to the New South Wales economy and employs 7.1% of the workforce.[85] In 2007, then-Premier of New South Wales Morris Iemma established Events New South Wales to "market Sydney and NSW as a leading global events destination". In July 2011 Events NSW merged with three key state authorities including Tourism NSW to establish Destination NSW (DNSW).[86]

New South Wales had a Gross State Product in 2018–19 (equivalent to Gross Domestic Product) of $614.4 billion which equalled $76,361 per capita.[4]

On 9 October 2007 NSW announced plans to build a 1,000 MW bank of wind powered turbines. The output of these is anticipated to be able to power up to 400,000 homes. The cost of this project will be $1.8 billion for 500 turbines.[87] On 28 August 2008 the New South Wales cabinet voted to privatise electricity retail, causing 1,500 electrical workers to strike after a large anti-privatisation campaign.[88]

The NSW business community is represented by the NSW Business Chamber which has 30,000 members.

Agriculture[]

Agriculture is spread throughout the eastern two-thirds of New South Wales. Cattle, sheep and pigs are the predominant types of livestock produced in NSW and they have been present since their importation during the earliest days of European settlement. Economically the state is the most important state in Australia, with about one-third of the country's sheep, one-fifth of its cattle, and one-third of its small number of pigs. New South Wales produces a large share of Australia's hay, fruit, legumes, lucerne, maize, nuts, wool, wheat, oats, oilseeds (about 51%), poultry, rice (about 99%),[89] vegetables, fishing including oyster farming, and forestry including wood chips.[90] Bananas and sugar are grown chiefly in the Clarence, Richmond and Tweed River areas.

Wools are produced on the Northern Tablelands as well as prime lambs and beef cattle. The cotton industry is centred in the Namoi Valley in northwestern New South Wales. On the central slopes there are many orchards, with the principal fruits grown being apples, cherries and pears. However, the fruit industry is threatened by the Queensland fruit fly (Bactrocera tyroni) which causes more than $28.5 million a year in damage to Australian crops, primarily in Queensland and northern New South Wales.[91]

About 40,200 hectares of vineyards lie across the eastern region of the state, with excellent wines produced in the Hunter Valley, with the Riverina being the largest wine producer in New South Wales.[92] Australia's largest and most valuable Thoroughbred horse breeding area is centred on Scone in the Hunter Valley.[93] The Hunter Valley is the home of the world-famous Coolmore,[94] Darley and Kia-Ora Thoroughbred horse studs.

About half of Australia's timber production is in New South Wales. Large areas of the state are now being replanted with eucalyptus forests.

Riparian water rights[]

Under the Water Management Act 2000, updated riparian water rights were given to those within NSW with livestock. This change was named "The Domestic Stock Right" which gives "an owner or occupier of a landholding is entitled to take water from a river, estuary or lake which fronts their land or from an aquifer which is underlying their land for domestic consumption and stock watering without the need for an access licence."[95]

Transport[]

Passage through New South Wales is vital for cross-continent transport. Rail and road traffic from Brisbane (Queensland) to Perth (Western Australia), or to Melbourne (Victoria) must pass through New South Wales.

Railways[]

The majority of railways in New South Wales are currently operated by the state government. Some lines began as branch-lines of railways starting in other states. For instance, Balranald near the Victorian border was connected by a rail line coming up from Victoria and into New South Wales. Another line beginning in Adelaide crossed over the border and stopped at Broken Hill.

Railways management are conducted by Sydney Trains and NSW TrainLink[96] which maintain rolling stock. Sydney Trains operates trains within Sydney while NSW TrainLink operates outside Sydney, intercity, country and interstate services.

Both Sydney Trains and NSW TrainLink have their main terminus at Sydney's Central station. NSW TrainLink regional and long-distance services consist of XPT services to Grafton, Casino, Brisbane, Melbourne and Dubbo, as well as Xplorer services to Canberra, Griffith, Broken Hill, Armidale and Moree. NSW TrainLink intercity trains operate on the Blue Mountains Line, Central Cost & Newcastle Line, South Coast Line, Southern Highlands Line and Hunter Line.

Roads[]

Major roads are the concern of both federal and state governments. The latter maintains these through Transport for NSW, formerly the Department of Roads and Maritime Services, and the Roads and Traffic Authority, and before that, the Department of Main Roads (DMR).

The main roads in New South Wales are

- Hume Highway linking Sydney to Melbourne, Victoria;

- Princes Highway linking Sydney to Melbourne via the Tasman Sea coast;

- Pacific Highway linking Sydney to Brisbane, Queensland via the Pacific coast;

- New England Highway running from the Pacific Highway, at Newcastle to Brisbane by an inland route;

- Federal Highway running from the Hume Highway south of Goulburn to Canberra, Australian Capital Territory;

- Sturt Highway running from the Hume Highway near Gundagai to Adelaide, South Australia;

- Newell Highway linking rural Victoria with Queensland, passing through the centre of New South Wales;

- Great Western Highway linking Sydney with Bathurst. As Route 32 it continues west as the Mitchell Highway then as the Barrier Highway to Adelaide via Broken Hill.

Other roads are usually the concern of the TfNSW and/or the local government authority.

Air[]

Kingsford Smith Airport (commonly Sydney Airport, and locally referred to as Mascot Airport or just 'Mascot'), located in the southern Sydney suburb of Mascot is the major airport for not just the state but the whole nation. It is a hub for Australia's national airline Qantas.

Other airlines serving regional New South Wales include:[97]

- FlyPelican[98]

- Jetstar[99]

- Regional Express (also known as Rex);[100]

- Virgin Australia[101] (formerly known as Virgin Blue Airlines).

- Corporate Air[102]

Ferries[]

Transdev Sydney Ferries operates Sydney Ferries services within Sydney Harbour and the Parramatta River, while Newcastle Transport has a ferry service within Newcastle.[103] All other ferry services are privately operated.[104]

Spirit of Tasmania ran a commercial ferry service between Sydney and Devonport, Tasmania. This service was terminated in 2006.[105]

Private boat services operated between South Australia, Victoria and New South Wales along the Murray and Darling Rivers but these only exist now as the occasional tourist paddle-wheeler service.[106]

National parks[]

New South Wales has more than 780 national parks and reserves covering more than 8% of the state.[107] These parks range from rainforests, waterfalls, rugged bush to marine wonderlands and outback deserts, including World Heritage sites.[108]

The Royal National Park on the southern outskirts of Sydney became Australia's first National Park when proclaimed on 26 April 1879. Originally named The National Park until 1955, this park was the second National Park to be established in the world after Yellowstone National Park in the U.S. Kosciuszko National Park is the largest park in state encompassing New South Wales' alpine region.[109]

The National Parks Association was formed in 1957 to create a system of national parks all over New South Wales which led to the formation of the National Parks and Wildlife Service in 1967.[110] This government agency is responsible for developing and maintaining the parks and reserve system, and conserving natural and cultural heritage, in the state of New South Wales. These parks preserve special habitats, plants and wildlife, such as the Wollemi National Park where the Wollemi Pine grows and areas sacred to Australian Aboriginals such as Mutawintji National Park in western New South Wales.

Sport[]

Throughout Australian history, New South Wales sporting teams have been very successful in domestic competitions and provided numerous players for the Australian national teams.

The largest sporting competition in the state is the National Rugby League, which is based in Sydney and expanded from the New South Wales Rugby League. The state is represented by the New South Wales Blues in the State of Origin series. Sydney is the spiritual home of Australian rugby league, and the state and hosts 10 of the 16 NRL teams; eight of these are based in the Sydney metropolitan area, namely the Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs, Cronulla Sharks, Manly Sea Eagles, Parramatta Eels, Penrith Panthers, South Sydney Rabbitohs, Sydney Roosters and Wests Tigers. The St George Illawarra Dragons are based in Wollongong, while the Newcastle Knights are located in Newcastle.

The state is represented by four teams in soccer's A-League: Sydney FC (2005–06, 2009–10, 2016–17 champions), Western Sydney Wanderers (2014 Asian champions), Central Coast Mariners (2012–13 champions) and Newcastle United Jets (2007–08 A League Champions).

Australian rules football has historically not been strong in New South Wales outside the Riverina region. However, the Sydney Swans relocated from South Melbourne in 1982 and their presence and success since the late 1990s has raised the profile of Australian rules football, especially after their AFL premiership in 2005. A second NSW AFL club, the Greater Western Sydney Giants, entered the competition in 2012.

The main summer sport is cricket and the Sydney Cricket Ground hosts the 'New Year' cricket Test match in January each year. The NSW Blues play in the One-Day Cup and Sheffield Shield competitions. Sydney Sixers and Sydney Thunder both play in the Big Bash League.

Other teams in major national competitions include the Sydney Kings and Hawks in the National Basketball League, Sydney Uni Flames in the Women's National Basketball League, New South Wales Waratahs in Super Rugby and New South Wales Swifts in Suncorp Super Netball.

Sydney was the host of the 1938 British Empire Games and 2000 Summer Olympics. The Stadium Australia hosts major events including the NRL Grand Final, State of Origin, rugby union and football internationals. It hosted the final of the 2003 Rugby World Cup and the 2015 AFC Asian Cup, as well as the 2006 FIFA World Cup qualifier between Australia and Uruguay, qualifying Australia for their first World Cup since 1974.

The annual Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race begins in Sydney Harbour on Boxing Day. Bathurst hosts the annual Bathurst 1000 as part of the Supercars Championship at Mount Panorama Circuit.

The popular equine sports of campdrafting and polocrosse were developed in New South Wales and competitions are now held across Australia. Polocrosse is now played in many overseas countries.

Major professional teams include:

- Australian rules football: Greater Western Sydney Giants, Sydney Swans

- Baseball: Sydney Blue Sox

- Basketball: Illawarra Hawks, Sydney Kings

- Cricket: New South Wales Blues, Sydney Sixers, Sydney Thunder

- Ice hockey: Newcastle Northstars, Sydney Bears, Sydney Ice Dogs

- Motor racing: Brad Jones Racing, Team Sydney

- Netball: New South Wales Swifts

- Rugby league:

- Representative: New South Wales Blues

- Clubs: Canterbury-Bankstown Bulldogs, Cronulla Sharks, Manly Sea Eagles, Newcastle Knights, Parramatta Eels, Penrith Panthers, South Sydney Rabbitohs, St George Illawarra Dragons, Sydney Roosters, Wests Tigers

- Rugby union: New South Wales Waratahs

- Soccer: Central Coast Mariners, Macarthur FC, Newcastle Jets, Sydney FC, Western Sydney Wanderers

Culture[]

As Australia's most populous state, New South Wales is home to a number of cultural institutions of importance to the nation. In music, New South Wales is home to the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, Australia's busiest and largest orchestra. Australia's largest opera company, Opera Australia, is headquartered in Sydney. Both of these organisations perform a subscription series at the Sydney Opera House. Other major musical bodies include the Australian Chamber Orchestra. Sydney is host to the Australian Ballet for its Sydney season (the ballet is headquartered in Melbourne). Apart from the Sydney Opera House, major musical performance venues include the City Recital Hall and the Sydney Town Hall.

New South Wales is home to several major museums and art galleries, including the Australian Museum, the Powerhouse Museum, the Museum of Sydney, the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Sydney is home to five Arts teaching organisations, which have all produced world-famous students: The National Art School, The College of Fine Arts, the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA), the Australian Film, Television & Radio School and the Conservatorium of Music (now part of the University of Sydney).

New South Wales is the setting and shooting location of many Australian films, including Mad Max 2, which was shot near the mining town of Broken Hill. The state has also attracted international productions, both as a setting, such as in Mission: Impossible 2, and as a stand-in for other locations, as seen in The Matrix franchise, The Great Gatsby and Unbroken.[113][114] 20th Century Fox operates Fox Studios Australia in Sydney. Screen NSW, which controls the state film industry, generates approximately $100 million into the New South Wales economy each year.[115]

Sister states[]

New South Wales in recent history has pursued bilateral partnerships with other federated states/provinces and metropolises through establishing a network of sister state relationships. The state currently has 7 sister states:[116]

- Guangdong, China (since 1979)

- Tokyo, Japan (since 1984)

- Ehime, Japan (since 1999)[117]

- North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany (since 1989)

- Seoul, South Korea (since 1991)

- Jakarta, Indonesia (since 1994)

- California, United States (since 1997)

See also[]

- Geology of New South Wales

- Index of Australia-related articles

- Outline of Australia

- Postage stamps and postal history of New South Wales

- Selection (Australian history)

- Squattocracy

Notes[]

- ^ In accordance with the Australian Bureau of Statistics source, England, Scotland, China and the Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau are listed separately

- ^ As a percentage of 6,969,686 persons who nominated their ancestry at the 2016 census.

- ^ The Australian Bureau of Statistics has stated that most who nominate "Australian" as their ancestry are part of the Anglo-Celtic group.[73]

- ^ Of any ancestry. Includes those identifying as Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

- ^ Of any ancestry. Includes those identifying as Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "National, state and territory population – September 2020". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The origin of the term 'cockroach'". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 13 June 2012. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jopson, Debra (23 May 2012). "Origin of the species: what a state we're in". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "5220.0 – Australian National Accounts: State Accounts, 2019–20". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 20 November 2020. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Floral Emblem of New South Wales". www.anbg.gov.auhi. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ "New South Wales". Parliament@Work. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "New South Wales". Geographical Names Register (GNR) of NSW. Geographical Names Board of New South Wales. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ "NSW State Flag & Emblems". NSW Government. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2016–17: Main Features". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 24 April 2018. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2018. Estimated resident population, 30 June 2017.

- ^ "Aboriginal settlement". About NSW. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b History of Aboriginal People of the Illawarra 1770 to 1970. Department of Environment and Conservation, NSW. 2005. p. 8.

- ^ Ross, Hannah; Farrow-Smith, Elloise; Herbert, Bronwyn (30 April 2019). "Byron Bay's Bundjalung people celebrate long-awaited land and sea native title determination". ABC News. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Beagleole, J. C. (1974). The Life of Captain James Cook. London: Adam and Charles Black. p. 249. ISBN 9780713613827.

- ^ Wharton, W.J.L (1893). "Preface". Captain Cook's Journal During the First Voyage Round the World. London: Eliot Stock – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Karskens, Grace (2013). "The early colonial presence, 1788-1822". In Bashford, Alison; MacIntyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 1, Indigenous and Colonial Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 91. ISBN 9781107011533.

- ^ Peter Hill (2008) p.141-150; Andrew Tink, Lord Sydney: The Life and Times of Tommy Townshend, Melbourne, Australian Scholarly Publishing, 2011.

- ^ "Governor Phillip's Instructions 25 April 1787 (UK)". Documenting a Democracy. National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 28 May 2006. Robert J. King, "Terra Australis, New Holland and New South Wales: the Treaty of Tordesillas and Australia", The Globe, no.47, 1998, pp.35–55.

- ^ Fletcher, B. H. (1967). Phillip, Arthur (1738–1814). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. pp. 326–333.

- ^ Karskens, Grace (2013). "The early colonial presence, 1788-1822". In Bashford, Alison; MacIntyre, Stuart (eds.). The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I, Indigenous and colonial Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–114. ISBN 9781107011533.

- ^ Whitaker, Anne-Maree (2009). "Castle Hill convict rebellion 1804". Dictionary of Sydney. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ "Castle Hill Rebellion". nma.gov.au. 30 June 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ Silver, Lynette Ramsay (1989). The Battle of Vinegar Hill: Australia's Irish Rebellion, 1804. Sydney, New South Wales: Doubleday. ISBN 0-86824-326-4.

- ^ Karskens, Grace (2013). pp. 115-17

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). A History of New South Wales. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 118–19. ISBN 9780521833844.

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). p. 2

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 19-21

- ^ Ford, Lisa; Roberts, David Andrew (2013). "Expansion, 1821-1850". The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I.

- ^ Hirst, John (2016). Australian History in 7 Questions. Victoria: Black Inc. pp. 51–54. ISBN 9781922231703.

- ^ Ford, Lisa; Roberts, David Andrew (2013). p.138

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 36, 55-57

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 57, 62, 64, 67

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 63, 76-77, 104

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 91-94

- ^ Hirst, John (2014). pp. 83-86

- ^ Irving, Helen (2013). "Making the federal Commonwealth". The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume I. pp. 249–51.

- ^ Irving, Helen (2013). pp. 257-62

- ^ Irving, Helen (2013). pp. 263-65

- ^ Croucher, John S. (2020). A Concise History of New South Wales. NSW: Woodslane Press. p. 128. ISBN 9781925868395.

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 110. 118-19

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 122-25

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 132, 142

- ^ Bongiorno, Frank (2013). "Search for a solution, 1923-39". The Cambridge History of Australia, Volume 2. pp. 79–81.

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 148-49

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 151, 157

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 157-58

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 161-62

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 156, 162, 168-75, 184-86

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 188, 193, 196-98

- ^ Rhodes, Campbell (27 October 2017). "Breaking up is hard to do: secession in Australia". Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "Parliament of New South Wales, Legislative Assembly election: Election of 1 May 1976". Australian Politics and Elections Archive 1856-2018. University of Western Australia. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ The Wran era. Bramston, Troy. Leichhardt, N.S.W.: Federation Press. 2006. p. 31. ISBN 1-86287-600-2. OCLC 225332582.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 231-34

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 234-238

- ^ Kingston, Beverley (2006). pp. 238, 241-46

- ^ Benson, Simon; Hildebrand, Joe (5 September 2008). "Nathan Rees new NSW premier after Morris Iemma quits". Courier Mail. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Keneally sworn in as state's first female premier". Herald Sun. Australia. 4 December 2009. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- ^ "NSW Premier Barry O'Farrell to resign over 'massive memory fail' at ICAC". ABC news. 17 April 2014.

- ^ Croucher, John S. (2020).p. 130

- ^ Joseph Henry Maiden. 1908. The Forest Flora of New South Wales, v. 3, Australian Government Printing Office.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan, Witch's Butter: Tremella mesenterica, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed; N. Stromberg Archived 21 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Australian Encyclopaedia, Vol. 7, Grolier Society.

- ^ "Geoscience Australia – Center of Australia, States and Territories". Archived from the original on 22 August 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Stormy Weather" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ Sharples, J.J. Mills, G.A., McRae, R.H.D., Weber, R.O. (2010) Elevated fire danger conditions associated with foehn-like winds in southeastern Australia. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology.

- ^ Rain Shadows by Don White. Australian Weather News. Willy Weather. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ And the outlook for winter is … wet by Kate Doyle from The New Daily. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "Rainfall and Temperature Records: National" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ "Official records for Australia in January". Daily Extremes. Bureau of Meteorology. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2013–14". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 31 March 2015. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2017–18". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 27 March 2019. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "2016 Community Profile". Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "2016 Census Community Profiles: New South Wales". Quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics; Commonwealth of Australia (January 1995). "Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Australia (Feature Article)". www.abs.gov.au. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics. "2016 Census Community Profiles: New South Wales - "General Community Profile" spreadsheet, tab "G14": Religious Affiliation by Sex". quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ "Constitution Act 1902". NSW Government. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "New South Wales Constitution Amendment (Pledge of Loyalty) Act 2006 No 6" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ Constitution Act 1902 (NSW), section 5.

- ^ Government Gazette June 1856

- ^ "EDUCATION ACT 1990 – SECT 21B Compulsory school-age". www.austlii.edu.au. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "Not so fast: minimum leaving age raised". www.abc.net.au. 27 January 2009. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "STAGES". www.abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "Schooling in NSW". educationstandards.nsw.edu.au. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "EDUCATION ACT 1990 – SECT 94 Record of School Achievement". www.austlii.edu.au. Archived from the original on 21 May 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ^ "Merchandise Exports" (PDF). Department of State and Regional Development. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2009.

- ^ Economic Contribution of Tourism to NSW 2012–13 – Destination NSW Archived 3 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. NSW Tourism Satellite Accounts, August 2007, cited at: Tourism New South Wales and there retrieved 2 May 2011

- ^ "About Us". Destination NSW. 11 October 2011. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ Australia to get 1,000 megawatt wind farm Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Susan Price (30 August 2008). "NSW power workers strike against privatisation". greenleft.org.au. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2008.

- ^ Agricultural Production Archived 7 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 7 March 2009.

- ^ Agriculture – Overview – Australia Archived 21 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lloyd, Annice C.; Hamacek, Edward L.; Kopittke, Rosemary A.; Peek, Thelma; Wyatt, Pauline M.; Neale, Christine J.; Eelkema, Marianne; Gu, Hainan (May 2010). "Area-wide management of fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in the Central Burnett district of Queensland, Australia". Crop Protection. 29 (5): 462–469. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2009.11.003. ISSN 0261-2194.

- ^ "From paddock to plate". Tourism New South Wales. New South Wales Government. 1 July 2003. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ^ SMH Travel – Scone Archived 25 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 7 March 2009.

- ^ "Australia | Stallions - Coolmore Ireland". Coolmore. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007.

- ^ "Domestic and stock rights". NSW Department of Primary Industries, Office of Water. 15 August 2014. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ^ "Transport for New South Wales". Transport for New South Wales. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ [1] NSW Rural and Regional Air Transport Operators Archived 11 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "FlyPelican". Archived from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Jetstar Archived 2 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine;

- ^ Rex Archived 2 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine;

- ^ "Virgin Australia". Virgin Australia. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ "Corporate Air". Corporate Air. Archived from the original on 31 October 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ "Stockton Ferry". Newcastlebuses.info. 26 August 2011. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ "List of Ferry Services". Transportnsw.info. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016.

- ^ "Spirit of Tasmania – Sydney Service". Spiritoftasmania.com.au. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ "Echuca Paddlesteamer". Archived from the original on 18 April 2012.

- ^ 2008 Guide to National Parks, p. 59, NSW NPWS.

- ^ Welcome to NSW National Parks Archived 6 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Office of Environment and Heritage, retrieved 2 May 2011

- ^ "Chisholm, Alec H.". The Australian Encyclopaedia. 6. Sydney: Halstead Press. 1963. p. 249. National Parks.

- ^ "Who We Are". National Parks Association of NSW. Archived from the original on 4 August 2007. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ^ "Broken Hill becomes first Australian city to join National Heritage List after decade-long campaign". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 20 January 2015. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ "National Heritage Places – City of Broken Hill". Department of the Environment. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Frater, Patrick (30 September 2013). "Angelina Jolie's 'Unbroken' Set to Shoot in Oz". Variety. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ^ Clifford, Catherine (14 December 2013). "Hollywood actor Angelina Jolie starts filming scenes for the movie 'Unbroken' in Werris Creek". ABC News. Archived from the original on 19 November 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ^ "Screen NSW Annual Report (2012–13)" (PDF). screen.nsw.gov.au. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ "Building international relationships". NSW Government. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ "International exchange activated with globalization". Ehime Prefecture. Archived from the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New South Wales. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for New South Wales. |

- Official NSW Website

- NSW Parliament

- Official NSW Tourism Website

- New South Wales at Curlie

Geographic data related to New South Wales at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to New South Wales at OpenStreetMap

- New South Wales

- States and territories of Australia

- States and territories established in 1788

- 1788 establishments in Australia