Energy in Australia

Energy in Australia is the production in Australia of energy and electricity, for consumption or export. Energy policy of Australia describes the politics of Australia as it relates to energy.

Australia is a net energy exporter, and was the fourth-highest coal producer in the world in 2009.

Historically–and until recent times–energy in Australia was sourced largely from coal and natural gas,[1] but due to the increasing effects of global warming and human-induced climate change on the global environment, there has been a shift towards renewable energy such as solar power and wind power both in Australia and abroad.[2][3] In 2020, renewable energy accounted for 27.7% of the total amount of electricity generated in Australia.[4]

Overview[]

| Year | Oil | Coal | Natural Gas | Renewables | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009-10 | 2,058 (34.6%) | 2,229 (37.5%) | 1,372 (23.1%) | 286 (4.8%) | 5,945 |

| 2010-11 | 2,195 (36.0%) | 2,129 (34.9%) | 1,516 (24.8%) | 260 (4.3%) | 6,100 |

| 2011-12 | 2,411 (38.9%) | 2,118 (34.2%) | 1,399 (22.6%) | 265 (4.3%) | 6,194 |

| 2012-13 | 2,221 (37.7%) | 1,946 (33.1%) | 1,386 (23.6%) | 330 (5.6%) | 5,884 |

| 2013-14 | 2,237.8 (38.4%) | 1,845.6 (31.7%) | 1,401.9 (24.0%) | 345.7 (5.9%) | 5,831.1 |

| 2014-15 | 2,237.4 (37.8%) | 1,907.8 (32.2%) | 1,431.0 (24.2%) | 343.3 (5.8%) | 5,919.6 |

| 2015-16 | 2,243.3 (37.0%) | 1,956.1 (32.2%) | 1,504.9 (24.8%) | 361.6 (6.0%) | 6,065.9 |

| 2016-17 | 2,315.4 (37.7%) | 1,936.9 (31.5%) | 1,515.0 (24.7%) | 378.7 (6.2%) | 6,145.8 |

| 2017-18 | 2,387.8 (38.7%) | 1,847.2 (29.9%) | 1,554.6 (25.2%) | 382.1 (6.2%) | 6,171.7 |

| 2018-19 | 2,402.1 (38.8%) | 1,801.6 (29.1%) | 1,592.7 (25.7%) | 399.6 (6.4%) | 6,196.0 |

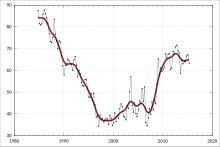

In 2009, Australia had the highest per capita CO2 emissions in the world. At that time, Maplecroft's CO2 Energy Emissions Index (CEEI) showed that Australia releases 20.58 tons of CO2 per person per year, more than any other country.[6] However, emissions have since been reduced. From 1990 to 2017, emissions per capita fell by one-third, with most of that drop occurring in the more recent years. Additionally, the emissions intensity of the economy fell by 58.4 percent during the same time period. These are the lowest values in 27 years.[7]

The energy sector in Australia increased its carbon dioxide emissions by 8.2% from 2004 to 2010 on average.

Fuels[]

Coal[]

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global coal production increased 23% from 2005 to 2010 and 4.7% from 2009 to 2010. In Australia, coal production increased 12.9% between 2005 and 2010 and 5.3% between 2009 and 2010.[8]

In 2009, Australia was the fourth-highest coal producer in the world, producing 335 megatonnes (Mt) of anthracite (black coal) and 64 Mt of lignite (brown coal).[9] Australia was the biggest anthracite exporter, with 31% of global exports (262 Mt out of 836 Mt total). Lignite is not exported. 78% of its 2009 anthracite production was exported (262 Mt out of 335 Mt total). In this respect, Australia is an exception to most anthracite exporters. Australia's global anthracite export share was 14% of all production (836 Mt out of 5,990 Mt total).[10]

In 2015, Australia was the biggest net exporter of coal, with 33% of global exports (392 Mt out of 1,193 Mt total). It was still the fourth-highest anthracite producer with 6.6% of global production (509 Mt out of 7,709 Mt total). 77% of production was exported (392 Mt out of 509 Mt total).[11][12]

Newcastle, New South Wales, is the world’s largest coal-export port. The Hunter Valley region in New South Wales is the chief coal region. Most coal mining in Australia is open cut.

Oil[]

Australia's oil production peaked in 2000, after gradually increasing since 1980.[13] Net oil imports rose from 7% of total consumption in 2000 to 39% in 2006. Decreasing domestic oil production is the result of the decline of oil-producing basins and few new fields going online.[13]

Natural gas[]

Australia's natural-gas reserves are an estimated 3,921 billion cubic metres (bcm), of which 20% are considered commercially proven (783 bcm). The gas basins with the largest recoverable reserves are the Carnarvon and Browse basins in Western Australia; the Bonaparte Basin in the Northern Territory; the Gippsland and Otway basins in Victoria and the Cooper-Eromanga basin in South Australia and Queensland. In 2014–2015 Australia produced 66 bcm of natural gas, of which approximately 80% was produced in Western Australia and Queensland regions.[14] Australia also produces LNG; LNG exports in 2004 were 7.9 Mt (10.7 bcm), 6% of world LNG trade.[15] Australia also has large deposits of coal seam methane (CSM), most of which are located in the anthracite deposits of Queensland and New South Wales.[15]

On 19 August 2009, Chinese petroleum company PetroChina signed a A$50 billion deal with American multinational petroleum company ExxonMobil to purchase liquefied natural gas from the Gorgon field in Western Australia,[16][17] the largest contract signed to date between China and Australia. It ensures China a steady supply of LPG fuel for 20 years, forming China's largest supply of relatively clean energy.[18][19] The agreement was reached despite relations between Australia and China being at their lowest point in years after the Rio Tinto espionage case and the granting of an Australian visa to Rebiya Kadeer.[20]

Oil shale[]

Australia's oil shale resources are estimated at about 58 billion barrels, or 4,531 million tonnes of shale oil. The deposits are located in the eastern and southern states, with the greatest feasibility in the eastern Queensland deposits. Between 1862 and 1952, Australia mined four million tonnes of oil shale. The mining stopped when government support ceased. Since the 1970s, oil companies have been exploring possible reserves. From 2000 to 2004, the Stuart Oil Shale Project near Gladstone, Queensland produced over 1.5 million barrels of oil. The facility, in operable condition, is on care and maintenance and its operator (Queensland Energy Resources) is conducting research and design studies for the next phase of its oil-shale operations.[21] A campaign by environmentalists opposed to the exploitation of oil-shale reserves may also have been a factor in its closure.[22]

Uranium[]

Australia has many Uranium deposits.[23]

Electricity[]

Since 2005, wind power and rooftop solar have led to an increasing share of renewable energy in total electricity generation.[24] Due to its large size and the location of its population, Australia lacks a single grid.[25]

| Year | Black Coal | Natural Gas | Brown Coal | Oil | Other | Fossil Fuels |

Wind | Hydro | Solar | Bio Energy | Renew- ables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009-10 | 51.5% (124,478) | 15.0% (36,223) | 23.2% (55,968) | 1.1% (2,691) | 1.0% (2,496) | 91.8% | 2.0% (4,798) | 5.2% (12,522) | 0.1% (278) | 0.9% (2,113) | 8.2% |

| 2010-11 | 46.3% (116,949) | 19.4% (48,996) | 21.9% (55,298) | 1.2% (3,094) | 1.1% (2,716) | 89.9% | 2.3% (5,807) | 6.7% (16,807) | 0.3% (850) | 0.8% (2,102) | 10.1% |

| 2011-12 | 47.4% (120,302) | 19.3% (48,892) | 21.7% (55,060) | 1.2% (3,070) | 1.0% (2,500) | 90.6% | 2.4% (6,113) | 5.5% (14,083) | 0.6% (1,489) | 0.9% (2,343) | 9.4% |

| 2012-13 | 44.8% (111,491) | 20.5% (51,053) | 19.1% (47,555) | 1.8% (4,464) | 0.8% (1,945) | 86.9% | 2.9% (7,328) | 7.3% (18,270) | 1.5% (3,817) | 1.3% (3,151) | 13.1% |

| 2013-14 | 42.6% (105,772.4) | 21.9% (54,393.9) | 18.6% (46,076.2) | 2.0% (5,012.4) | - | 85.1% | 4.1% (10,252.0) | 7.4% (18,421.0) | 2.0% (4,857.5) | 1.4% (3,511.3) | 14.9% |

| 2014-15 | 42.7% (107,639) | 20.8% (52,463) | 20.2% (50,970) | 2.7% (6,799) | - | 86.3% | 4.5% (11,467) | 5.3% (13,445) | 2.4% (5,968) | 1.4% (3,608) | 13.7% |

| 2015-16 | 44.4% (114,295) | 19.6% (50,536) | 19.0% (48,796) | 2.2% (5,656) | - | 85.2% | 4.7% (12,199) | 6.0% (15,318) | 2.7% (6,838) | 1.5% (3,790) | 14.8% |

| 2016-17 | 45.8% (118,272) | 19.6% (50,460) | 16.9% (43,558) | 1.9% (4,904) | - | 84.3% | 4.9% (12,597) | 6.3% (16,285) | 3.1% (8,072) | 1.4% (3,501) | 15.7% |

| 2017-18 | 46.6% (121,702) | 20.6% (53,882) | 13.8% (36,008) | 1.9% (4,904) | - | 82.9% | 5.8% (15,174) | 6.1% (16,021) | 3.8% (9,930) | 1.3% (3,518) | 17.1% |

| 2018-19 | 45.4% (119,845) | 20.0% (52,775) | 13.1% (34,460) | 1.9% (4,923) | - | 80.3% | 6.7% (17,712) | 6.0% (15,967) | 5.6% (14,849) | 1.3% (3,496) | 19.7% |

Electricity supply[]

As of 2011, electricity producers in Australia were not building gas-fired power stations,[26] while the four major banks were unwilling to make loans for coal-fired power stations, according to EnergyAustralia (formerly TRUenergy).[27] In 2014, an oversupply of generation was expected to persist until 2024.[28] However, a report published in 2017 by the Australian Energy Market Operator projected that energy supply in 2018 and 2019 is expected to meet demands, with a risk of supply falling short at peak demand times.[29]

From 2003 to 2013 real electric prices for households increased by an average of 72%. Much of this increase in price has been attributed to over-investment in increasing distribution networks and capacity. Further price increases are predicted to be moderate over the next few years (2017 on) due to changes in the regulation of transmission and distribution networks as well as increased competition in electricity wholesale markets as supply and demand merge.[30]

Renewable energy[]

Renewable energy has potential in Australia, and the Climate Change Authority is reviewing the 20-percent Renewable Energy Target (RET). The production of 50 megawatts of wind power (power for nearly 21,000 homes annually) creates about 50 construction jobs and five staff positions.[31][32] In recent years, wind and solar power have been the fastest growing source of energy in Australia.[33] Geothermal energy is also growing, but at the present time, it only accounts for a small portion of energy in Australia.

Energy efficiency[]

Lower energy use could save A$25 billion, or A$840 per electricity customer, according to EnergyAustralia.[34]

Climate change[]

Australian total emissions in 2007 were 396 million tonnes of CO2. That year, the country was among the top polluter nations of the world per capita. Australian per-capita emissions of carbon dioxide in 2007 were 18.8 tons of CO2, compared to the EU average of 7.9 tons. The change in emissions from 1990 to 2007 was +52.5 percent, compared to the EU's -3.3 percent.[35] The per-capita carbon footprint in Australia was rated 12th in the world by PNAS in 2011.[36]

Due to climate change, Australia is expected to experience harsher extreme weather events, mainly bush-fires and floods during summer.[37] Rising sea levels are of particular concern for Australia, because most of the population lives in the coast (around 85%).[38]

Employment[]

When analysing employment data, the Australian Bureau of Statistics classifies the electricity and gas supply industry as part of the Electricity, Gas, Water and Waste Services Division.[39] That division is the smallest industry in Australia in terms of employment.[40]

In November 2017, the number of people employed in electricity supply, which includes electricity generation, transmission and distribution, was 64,200 (47,700 males, 16,600 females).[41] The number of people employed in gas supply was 11,200 (9,000 males, 2,200 females).[41] The total number of persons employed in electricity and gas supply industries was 75,400.[41] This represents about 0.67 percent of all employed persons in Australia.[a]

In 2016, the major occupations in this Division were truck drivers (9,900), electricians (7,700), electrical distribution trades workers (5,400), and electrical engineers (4,400).[42][a]

Employment in renewable energy activities[]

In 2015–16, annual direct full-time equivalent employment in renewable energy in Australia was estimated at 11,150. Employment in renewables peaked in 2011–12, probably due to the employment of construction workers to build renewable energy facilities. However, it decreased by 36 percent in 2014–15, and by a further 16 percent in 2015–16. The decline is attributed to a decrease in the number of roof-top solar photovoltaic systems being installed on houses. Once construction of renewable energy facilities is completed, and only ongoing maintenance is required, employment falls quite significantly.[43]

For most Australian states and territories the major contributor to employment in renewable energy is solar power. Employment in roof-top solar photovoltaic systems, including solar hot water systems, comprised half of all employment in renewable energy in 2015–16. Employment in large scale solar and wind power is driven primarily by installation activity, rather than ongoing operation and maintenance.[43]

In Western Australia, 93 percent of all jobs in renewable energy are in solar power. The proportion of employment in biomass is significantly greater in Queensland (42 percent), where the sugar industry makes great use of sugar cane to generate electricity for sugar milling and to feed into the grid. Most jobs in Tasmania’s renewable energy industry are in hydropower (87 percent).[43]

Jobs in the renewable energy industry are forecast to grow substantially by 2030, driven by growth in electricity demand and new renewable energy capacity.[44]: 16 Conversely, jobs associated with coal-fired power stations are forecast to decline as those plants age and close. Such job losses would disproportionately affect some regional areas, such as the Latrobe Valley in Victoria, Newcastle and the Hunter Valley in New South Wales, Gladstone and Rockhampton in Queensland, and Collie in Western Australia. However, it is expected that the number of jobs created in renewable energy will far exceed the number of jobs lost in coal-based generation.[44]: 35

Energy policy of Australia[]

Finkel Report[]

In June 2017 Alan Finkel released The Independent Review into the Future Security of the National Electricity Market (commonly referred to as the Finkel Report), which proposed an approach to increasing energy security and reliability through four outcomes. These would be: increased security, future reliability, rewarding consumers, and lower emissions. The report ultimately recommended a (CET) to provide incentives for growth in renewable energies.[45]

The reaction to the report by scientific experts in the field leaned more towards positive. Positive reactions to the Report were due to the national strategy plan that provides a CET for Australia, creating customer incentives, and takes politics out of energy policy to help meet the Paris Agreement. Additionally, the Finkel Report was commended for recognizing the current technologies available and including market forces in its solutions by the Australian Academy of Technology Engineering.[46]

National Energy Guarantee[]

On 17 October 2017, the Australian Government rejected Finkel's CET proposal, in favour of what it called the National Energy Guarantee (NEG), to reduce power prices and prevent blackouts. The strategy calls on electricity retailers to meet separate reliability and emissions requirements, rather than Dr Finkel’s CET recommendation. Under the plan, retailers have to provide a minimum amount of baseload power from coal, gas or hydro, while also providing a specified level of low emissions energy.[47] NEG has been criticised as turning away from renewable energy.[48] In October 2018, the Australian Government announced that it will not continue with the Guarantee.[49][50]

See also[]

- Fossil-fuel phase-out

- List of coal-fired power stations in Australia

- List of natural gas fired power stations in Australia

- Australian Renewable Energy Agency

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b These figures are rounded to the nearest 100 persons

References[]

- ^ "Australia Country Analysis Brief". 2002. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ "New Zealand says goodbye to coal power". antinuclear.net. 7 August 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "China starts moving away from coal based energy". Spokesman.com. 13 September 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Clean Energy Council Australia. "Clean Energy Australia Report 2021" (PDF). Clean Energy Australia. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Australian Energy Statistics | energy.gov.au". www.energy.gov.au. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ "The World's Biggest Polluters". The New Ecologist. 15 October 2009. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ Energy, Department of the Environment and (26 July 2017). "Department of the Environment and Energy". Department of the Environment and Energy. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ IEA Key World Energy Statistics 2011 October 2011

- ^ IEA Key energy statistics 2010 Pages: 15

- ^ IEA Key energy statistics 2010 Pages:15

- ^ IEA Key World Energy Statistics 2016 (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2016. p. 15.

- ^ "Key Coal Trends. Excerpt from: Coal information" (PDF). Information Energy Agency (IEA). 1 January 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Australia: Energy profile Archived 1 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine 26 June 2007, Energy Publisher accessdate 3 July 2011

- ^ "Australian Energy Statistics".

- ^ Jump up to: a b OECD/IEA, pp. 131–137

- ^ Stephen McDonell, 19 August 2009, Record gas deal between China and Australia – AM – Australian Broadcasting Corporation

- ^ Babs McHugh, 19 August 2009, Massive sale from Gorgon Gas Project – Australian Broadcasting Corporation

- ^ David McLennan, 20 August 2009, Australia to be 'global supplier of clean energy' – The Canberra Times

- ^ 20 August 2009, CNPC to import 2.25m tons of LNG annually from Australia – ChinaDaily (Source: Xinhua)

- ^ Peter Ryan, 19 August 2009, Deal means 2.2 million tonnes exported per year – AM – Australian Broadcasting Corporation

- ^ Shale oil. AIMR Report 2006 Geoscience Australia, accessdate=30 May 2007 [1] archivedate 13 February 2007

- ^ Climate-changing shale oil industry stopped Greenpeace Australia Pacific, 3 March 2005, accessdate 28 June 2007

- ^ https://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/uranium-resources/supply-of-uranium.aspx

- ^ "State of the energy market, 2020 | Australian Energy Regulator". www.aer.gov.au. Retrieved 11 July 2017. Comparable to previous years statistical calculation criteria, 2018, 2017, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, and 2010

- ^ http://www.genifoundation.org.au/images/Energy_Grid_Aust_2009_April_m.jpg

- ^ (22 May 2011).Carbon tax is delaying investment: McIndoe. Inside Business. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved on 12 March 2012.

- ^ Royce Millar & Adam Morton (21 May 2011). Big banks 'no' to coal plant. The Age. Fairfax Media. Retrieved on 12 March 2012.

- ^ Mark, David (8 August 2014). "Australia faces unprecedented oversupply of energy, no new energy generation needed for 10 years: report". ABC. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ "Energy Supply Outlook" (PDF). AEMO. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ Swoboda, Kai. "Energy prices—the story behind rising costs". Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ scheme (2012).Energy Council[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Wind Farm Investment, Employment and Carbon Abatement in Australia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ https://www.solarchoice.net.au/blog/australia-tipped-to-add-70000-home-batteries-in-2019-lead-global-demand/

- ^ "Australia's largest solar farm opens amid renewable target debate". The Guardian. 10 October 2012.

The Greenough River Solar project in Western Australia is expected to have enough capacity to power 3,000 homes.

- ^ Energy in Sweden 2010 Archived 16 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Table 1: Emissions of carbon dioxide in total, per capita and per GDP in EU and OECD countries, 2007

- ^ Which nations are really responsible for climate change - interactive map The Guardian 8 December 2011 (All goods and services consumed, source: Peters et al PNAS, 2011)

- ^ Head, Lesley; Adams, Michael; McGregor, Helen V.; Toole, Stephanie (1 March 2014). "Climate change and Australia". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 5 (2): 175–197. doi:10.1002/wcc.255. ISSN 1757-7799.

- ^ Energy, Department of the Environment and (2 June 2014). "Department of the Environment and Energy". Department of the Environment and Energy. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics; Statistics New Zealand (2006). Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification 2006 (ANZSIC) (PDF) (Report). Australian Bureau of Statistics. p. 200.

- ^ "Electricity, Gas, Water, Waste Services". Job Outlook. Retrieved 22 December 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017). 6291.0.55.003 - Labour Force, Australia, Detailed, Quarterly, Nov 2017, Table 06. Employed persons by Industry sub-division of main job (ANZSIC) and Sex (Report). Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ Department of Employment, Australian Government (2016). 4. Main Employing Occupations (Report). Department of Employment, Australian Government.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017). 4631.0 - Employment in Renewable Energy Activities, Australia, 2015-16 (Report). Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Climate Council of Australia (2016). Renewable Energy Jobs: Future Growth in Australia (PDF). Climate Council of Australia. ISBN 978-0-9945973-3-5.

- ^ Finkel, Alan. "Independent Review into the Future Security of the National Electricity Market" (PDF). Department of the Environment and Energy. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ SCIMEX (9 June 2017). "EXPERT REACTION: Finkel Report - Independent Review into the Future Security of the National Electricity Market". Scimex. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Government ditches chief scientist’s energy plan, but Alan Finkel backs the new one

- ^ "Australia rejects chief scientist's clean energy proposal". BBC. 17 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ Mills, Chanel (16 October 2017). "National Energy Guarantee". www.coagenergycouncil.gov.au. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ staff, The Guardian (8 September 2018). "Scott Morrison says national energy guarantee 'is dead'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- Energy in Australia