Monarchy of Australia

| Queen of Australia | |

|---|---|

Federal | |

Coat of Arms of Australia | |

| Incumbent | |

The Queen wearing the insignia of the Sovereign of the Order of Australia | |

| Elizabeth II since 6 February 1952 | |

| Details | |

| Style | Her Majesty |

| Heir apparent | Charles, Prince of Wales |

| Residence | Government House, Canberra |

Politics of Australia |

|---|

|

|

Constitution |

|

The monarchy of Australia is the institution in which a person serves as Australia's sovereign and head of state, on a hereditary basis. The Australian monarchy is a constitutional monarchy, modelled on the Westminster system of parliamentary government, while incorporating features unique to the Constitution of Australia.

The present monarch is Elizabeth II, styled Queen of Australia,[1] who has reigned since 6 February 1952. She is represented in Australia as a whole by the Governor-General, in accordance with the Australian Constitution[2] and letters patent from the Queen,[3][4][5] and in each of the Australian states, according to the state constitutions, by a governor, assisted by a lieutenant-governor. The monarch appoints the Governor-General and the governors, on the advice of the respective executive governments; State and Federal. These are now almost the only constitutional functions of the monarch with regard to Australia.[6]

Australian constitutional law provides that the monarch of the United Kingdom is also the monarch in Australia.[7] This is understood today to constitute a separate Australian monarchy, the monarch acting with regard to Australian affairs exclusively upon the advice of Australian ministers. Australia is thus one of the Commonwealth realms, sixteen independent countries that share the same person as monarch and head of state.

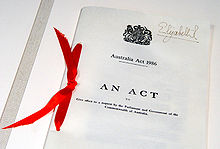

International and domestic aspects[]

Key features of Australia's system of government include its basis in a combination of "written" and "unwritten rules", and its heads of state, comprising the Sovereign, the State Governors, and the Governor-General.[8] The monarch of Australia is the same person as the monarch of the 15 other Commonwealth realms within the 54-member Commonwealth of Nations; however, each realm is independent of the others, with the monarchy having a separate character in each.[9][10] Effective with the Australia Act 1986, no British government can advise the monarch on any matters pertinent to Australia. On all matters of the Australian Commonwealth, the monarch is advised by Australian federal ministers of the Crown,[11] Likewise, on all matters relating to any Australian state, the monarch is advised by the ministers of the Crown of that state. In 1999 the High Court of Australia held in Sue v Hill that, at least since the Australia Act 1986, Britain has been a foreign power in regard to Australia's domestic and foreign affairs; it followed that a British citizen was a citizen of a foreign power and incapable of being a member of the Australian Parliament, pursuant to Section 44(i) of the Australian Constitution.[10][12] In 2001 the High Court held that, until the United Kingdom became a foreign power, all British subjects were subjects of the Queen in right of the United Kingdom and thus could not be classified as aliens within the meaning of Section 51(xix) of the constitution.[13][14][15]

Title[]

The sovereign's Australian title is currently Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God Queen of Australia and Her other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth.[1]

Prior to 1953, the title had simply been the same as that in the United Kingdom. A change in the title resulted from occasional discussion and an eventual meeting of Commonwealth representatives in London in December 1952, at which Canada's preferred format for the monarch's title was Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God, Queen of [Realm] and of Her other realms and territories, Head of the Commonwealth, Defender of the Faith.[16] Australia, however, wished to have the United Kingdom mentioned as well.[17] Thus, the resolution was a title that included the United Kingdom but, for the first time, also separately mentioned Australia and the other Commonwealth realms. The passage of a new Royal Style and Titles Act by the Parliament of Australia put these recommendations into law.[18]

It was proposed by the Cabinet headed by Gough Whitlam that the title be amended to "denote the precedence of Australia, the equality of the United Kingdom and each other sovereign nation under the Crown, and the separation of Church and State." A new Royal Titles and Styles Bill that removed specific reference to the monarch's role as Queen of the United Kingdom was passed by the federal parliament, but the Governor-General, Sir Paul Hasluck, reserved Royal Assent "for Her Majesty's pleasure" (similarly to Governor-General Sir William McKell's actions with the 1953 Royal Titles and Styles Bill). Queen Elizabeth II signed her assent at Government House, Canberra, on 19 October 1973.[1]

Finance[]

In 2018, a trip by the Prince of Wales to the Commonwealth country of Vanuatu, escorted by Australian Minister for Foreign Affairs Julie Bishop in between a tour of Queensland and the Northern Territory, was paid for by Australian taxpayers.[19]

In October 2011, the cost of a 10-day royal visit to Australia was put at $5.85 million.[20]

Personification of the state[]

The monarch is also the locus of oaths of allegiance; many employees of the Crown are required by law to recite this oath before taking their posts, such as all members of the Commonwealth parliament, all members of the state and territorial parliaments, as well as all magistrates, judges, police officers and justices of the peace. This is in reciprocation to the sovereign's Coronation Oath, wherein he or she promises "to govern the Peoples of... Australia... according to their respective laws and customs".[21] New appointees to the Federal Cabinet currently also swear an oath that includes allegiance to the monarch before taking their post.[22] However, as this oath is not written in law, it has not always been observed and depends on the form chosen by the prime minister of the time, suggested to the Governor-General. In December 2007, Kevin Rudd did not swear allegiance to the sovereign when sworn in by the Governor-General, making him the first prime minister not to do so;[citation needed] however, he (like all other members of parliament) did swear allegiance to the Queen, as required by law, when sworn in by the Governor-General as newly elected parliamentarians. Similarly, the Oath of Citizenship contained a statement of allegiance to the reigning monarch until 1994, when a pledge of allegiance to "Australia" and its values was introduced. The High Court found, in 2002, though, that allegiance to the Queen of Australia was the "fundamental criterion of membership" in the Australian body politic, from a constitutional, rather than statutory, point of view.[15]

Head of state[]

Key features of Australia's system of government include its basis on a combination of "written" and "unwritten rules", and its heads of state, comprising the Sovereign and the State Governors, and the Governor-General.[8] The constitution does not mention the term "head of state". The Constitution defines the Governor-General as the monarch's representative.[23] According to the Australian Parliamentary Library, Australia's head of state is the monarch, and its head of government is the prime minister, with powers limited by both law and convention for government to be carried on democratically.[24] The federal constitution provides that the monarch is part of the Parliament and is empowered to appoint the Governor-General as the monarch's representative, while the executive power of the Commonwealth which is vested in the monarch is exercisable by the Governor-General as the monarch's representative. The few functions which the monarch does perform (such as appointing the Governor-General) are done on advice from the prime minister.[25]

A review of the political situation in Australia from the 1970s to the present shows that, while the position of the monarch as head of state has not been altered, some Australians have argued in favour of changing the constitution into a form of republican government that would, they propose, be better suited to the Commonwealth of Australia than the current monarchy.[26] While current official sources use the description "head of state" for the monarch, in the lead up to the republic referendum in 1999, Sir David Smith proposed an alternative explanation, that Australia already has a head of state in the person of the Governor-General, who since 1965 has invariably been an Australian citizen. This view has some support within the group Australians for Constitutional Monarchy.[27] It is designed to counter the objections by republicans, such as the Australian Republic Movement, that no Australian can become, or can be involved in choosing, the Australian head of state.[28] The leading textbook on Australian constitutional law formulates the position thus: "The Queen, as represented in Australia by the Governor-General, is Australia's head of state."[29]

Constitutional role and royal prerogative[]

We have a very good system now in terms of political stability... one of the reasons why we have had this wonderful stability is because of the constitutional linkages from Crown to Governor-General to Prime Minister at the Federal level, and Crown to Governor to Premiers at the State level. There are checks and balances in the system, and that is why we never had civil wars, that is why we never had huge political upheavals except in '32 and '75. So the system as it is has worked very well.[30]

— Governor-General Michael Jeffery, 2003

Foreign affairs[]

The royal prerogative also extends to foreign affairs: the Governor-General-in-Council negotiates and ratifies treaties, alliances, and international agreements.[31] As with other uses of the royal prerogative, no parliamentary approval is required.[32]

Parliament[]

The sovereign, along with the Senate and the House of Representatives, being one of the three components of parliament, is called the Queen-in-Parliament. The authority of the Crown therein is embodied in the mace (House of Representatives) and Black Rod (Senate), which both bear a crown at their apex. The monarch and viceroy do not, however, participate in the legislative process save for the granting of Royal Assent by the Governor-General. Further, the constitution outlines that the Governor-General alone is responsible for summoning, proroguing, and dissolving parliament.[33]

All laws in Australia, except in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) Legislative Assembly, are enacted only with the granting of Royal Assent, done by the Governor-General, relevant state governor, or Administrator in the case of the Northern Territory (NT), with the Great Seal of Australia or the appropriate state or territory seal. Laws passed by the ACT and NT legislatures, unlike their state counterparts, are subject to the oversight of the government of Australia and can be disallowed by the Australian Parliament. The Governor-General may reserve a bill "for the Queen's pleasure"; that is withhold his consent to the bill and present it to the sovereign for her personal decision. Under the constitution, the sovereign also has the power to disallow a bill within one year of the Governor-General having granted Royal Assent.[34]

Courts[]

In the United Kingdom, the sovereign is deemed the fount of justice.[35][36] However, he or she does not personally rule in judicial cases,[35] meaning that judicial functions are normally performed only in the monarch's name. Criminal offences are legally deemed to be offences against the sovereign and proceedings for indictable offences are brought in the sovereign's name in the form of The Queen [or King] against [Name] (sometimes also referred to as the Crown against [Name]).[37][38] Hence, the common law holds that the sovereign "can do no wrong"; the monarch cannot be prosecuted in his or her own courts for criminal offences. Civil lawsuits against the Crown in its public capacity (that is, lawsuits against the government) are permitted; however, lawsuits against the monarch personally are not cognisable. In international cases, as a sovereign and under established principles of international law, the Queen of Australia is not subject to suit in foreign courts without her express consent. The prerogative of mercy lies with the monarch, and is exercised in the state jurisdictions by the governors.[39]

Cultural role[]

Royal presence and duties[]

Official duties involve the sovereign representing the state at home or abroad, or other royal family members participating in a government-organised ceremony either in Australia or elsewhere.[40] The sovereign and/or his or her family have participated in events such as various centennials and bicentennials; Australia Day; the openings of Olympic and other games; award ceremonies; D-Day commemorations; anniversaries of the monarch's accession; and the like. Other royals have participated in Australian ceremonies or undertaken duties abroad, such as Prince Charles at the Anzac Day ceremonies at Gallipoli, or when the Queen, Prince Charles, and Princess Anne participated in Australian ceremonies for the anniversary of D-Day in France in 2004. On 22 February 2009, Princess Anne represented the Queen at the National Bushfires Memorial Service in Melbourne.[41][42] The Queen also showed her support for the people of Australia by making a personal statement about the bushfires[43] and by also making a private donation to the Australian Red Cross Appeal.[44] The Duke of Edinburgh was the first to sign a book of condolences at the Australian High Commission in London.[44]

Religious role[]

Until its new constitution went into force in 1962, the Anglican Church of Australia was part of the Church of England. Its titular head was consequently the monarch, in his or her capacity as Supreme Governor of the Church of England.[45] However, unlike in England, Anglicanism was never established as a state religion in Australia.[46]

Vice-regal residences[]

The Governor-General has two official residences, Government House in Canberra, commonly known as "Yarralumla", and Admiralty House in Sydney. The Australian monarch stays there when visiting Canberra, as do visiting heads of state.[47]

Australian Defence Force[]

Section 68 of the Australian Constitution says: "The command in chief of the naval and military forces of the Commonwealth is vested in the Governor-General as the Queen's representative." In practice, however, the Governor-General does not play any part in the ADF's command structure other than following the advice of the Minister for Defence in the normal form of executive government.[48]

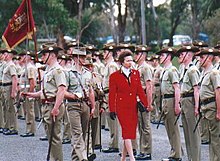

Australian naval vessels bear the prefix Her Majesty's Australian Ship (HMAS) and many regiments carry the "royal" prefix.[49] Members of the Royal Family have presided over military ceremonies, including Trooping the Colours, inspections of the troops, and anniversaries of key battles. When the Queen is in Canberra, she lays a wreath at the Australian War Memorial. In 2003, the Queen acted in her capacity as Australian monarch when she dedicated the Australian War Memorial in Hyde Park, London.[1]

Some members of the Royal Family are Colonels-in-Chief of Australian regiments, including: the Royal Regiment of Australian Artillery; Royal Australian Army Medical Corps; the Royal Australian Armoured Corps and the Royal Australian Corps of Signals, amongst many others. The Queen's late husband, the Duke of Edinburgh, was an Admiral of the Fleet.[50]

History[]

The development of a distinctly Australian monarchy came about through a complex set of incremental events, beginning in 1770, when Captain James Cook, in the name of, and under instruction from, King George III, claimed the east coast of Australia.[51] Colonies were eventually founded across the continent,[52][53] all of them ruled by the monarch of the United Kingdom, upon the advice of his or her British ministers, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, in particular. After Queen Victoria's granting of Royal Assent to the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act on 9 July 1900, which brought about Federation in 1901, whereupon the six colonies became the states of Australia, the relationship between the state governments and the Crown remained as it was pre-1901: References in the constitution to "the Queen" meant the government of the United Kingdom (in the formation of which Australians had no say)[11] and the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865 – by which colonial laws deemed repugnant to imperial (British) law in force in the colony were rendered void and inoperative – remained in force in both the federal and state spheres;[54] and all the governors, both of the Commonwealth and the states, remained appointees of the British monarch on the advice of the British Cabinet,[55] a situation that continued even after Australia was recognised as a Dominion of the British Empire in 1907.[56]

In response to calls from some Dominions for a re-evaluation in their status under the Crown after their sacrifice and performance in the First World War,[29]: 110 a series of Imperial Conferences was held in London, from 1917 on, which resulted in the Balfour Declaration of 1926, which provided that the United Kingdom and the Dominions were to be considered as "autonomous communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate to one another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the Crown." The Royal and Parliamentary Titles Act, 1927, an Act of the Westminster Parliament, was the first indication of a shift in the law, before the Imperial Conference of 1930 established that the Australian Cabinet could advise the sovereign directly on the choice of Governor-General, which ensured the independence of the office.[57] The Crown was further separated amongst its dominions by the Statute of Westminster 1931,[58] and, though it was not adopted by Australia until 1942 (retroactive to 3 September 1939).[59]

The Curtin Labor Government appointed Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, as Governor-General during the Second World War. Curtin hoped the appointment might influence the British to despatch men and equipment to the Pacific War, and the selection of the brother of King George VI reaffirmed the important role of the Crown to the Australian nation at that time.[60] The Queen became the first reigning monarch to visit Australia in 1954, greeted by huge crowds across the nation. Her son Prince Charles attended school in Australia in 1967.[61] Her grandson Prince Harry undertook a portion of his gap-year living and working in Australia in 2003.[62]

The sovereign did not possess a title unique to Australia until the Australian parliament enacted the Royal Styles and Titles Act in 1953,[18] after the accession of Elizabeth to the throne, and giving her the title of Queen of the United Kingdom, Australia and Her other Realms and Territories. Still, Elizabeth remained both as a queen who reigned in Australia both as Queen of Australia (in the federal jurisdiction) and Queen of the United Kingdom (in each of the states), as a result of the states not wishing to have the Statute of Westminster apply to them, believing that the status quo better protected their sovereign interests against an expansionist federal government, which left the Colonial Laws Validity Act in effect. Thus, the British government could still – at least in theory, if not with some difficulty in practice – legislate for the Australian states, and the viceroys in the states were appointed by and represented the sovereign of the United Kingdom, not that of Australia;[63] as late as 1976, the British ministry advised the Queen to reject Colin Hannah as the nominee of the Queensland Cabinet for governor,[64] and court cases from Australian states could be appealed directly to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, thereby bypassing the Australian High Court. It was with the passage of the Australia Act in 1986, which repealed the Colonial Laws Validity Act and abolished appeals of state cases to London, that the final vestiges of the British monarchy in Australia were removed, leaving a distinct Australian monarchy for the nation. The view in the Republic Advisory Committee's report in 1993 was that if, in 1901, Victoria, as Queen-Empress, symbolised the British Empire of which all Australians were subjects, all of the powers vested in the monarch under Australia's Constitution were now exercised on the advice of the Australian government.[11]

The 1999 Australian republic referendum was defeated by 54.4% of the populace, despite polls showing that the majority supported becoming a republic.[65] It is believed the proposed model of the republic (not having a directly elected president) was unsatisfactory to most Australians.[66] The referendum followed the recommendation of a 1998 Constitutional Convention called to discuss the issue of Australia becoming a republic. Still, nearly another ten years later, Kevin Rudd was appointed as Prime Minister, whereafter he affirmed that a republic was still a part of his party's platform, and stated his belief that the debate on constitutional change should continue.[67]

The previous Prime Minister, Julia Gillard re-affirmed her party's platform about a possible future republic. She stated that she would like to see Australia become a republic, with an appropriate time being when there is a change in monarch. A statement unaligned to this position was recorded on 21 October 2011 at a reception in the presence of the Queen at Parliament House in Canberra when Gillard stated that the monarch is "a vital constitutional part of Australian democracy and would only ever be welcomed as a beloved and respected friend."[68] The then Opposition Leader, Tony Abbott, a former head of Australians for Constitutional Monarchy stated on 21 October 2011, "Your Majesty, while 11 prime ministers and no less than 17 opposition leaders have come and gone, for 60 years you have been a presence in our national story and given the vagaries of public life, I'm confident that this will not be the final tally of the politicians that you have outlasted."[69]

A Morgan poll taken in October 2011 found that support for constitutional change was at its lowest for 20 years. Of those surveyed 34% were pro-republic as opposed to 55% pro-monarchist, preferring to maintain the current constitutional arrangements.[70] A peer-reviewed study published in the Australian Journal of Political Science in 2016 found that there had been a significant improvement to support for monarchy in Australia after a twenty-year rapid decline following the 1992 annus horribilis.[71]

A poll in November 2018 found support for the monarchy has climbed to a record high.[72] A YouGov poll in July 2020 found that 62 percent of respondents supporting replacing the monarch with an Australian head of state.[73]

List of monarchs of Australia[]

| No. | Portrait | Regnal name (Birth–Death) Royal dynasty |

Reign over Australia | Full name | Consort | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

George III (1738–1820) House of Hanover |

29 April 1770 | 29 January 1820 | George William Frederick | Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz |

| Governors of New South Wales: Arthur Phillip, John Hunter, Philip King, William Bligh, Lachlan Macquarie | ||||||

| 2 |

|

George IV (1762–1830) House of Hanover |

29 January 1820 | 26 June 1830 | George Augustus Frederick | Caroline of Brunswick |

| Governors of New South Wales: Sir Thomas Brisbane, Sir Ralph Darling | ||||||

| 3 |

|

William IV (1765–1837) House of Hanover |

26 June 1830 | 20 June 1837 | William Henry | Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen |

| Governor of New South Wales: Sir Richard Bourke Governor of Western Australia: Sir James Stirling Governor of South Australia: Sir John Hindmarsh | ||||||

| 4 |

|

Victoria (1819–1901) House of Hanover |

20 June 1837 | 22 January 1901 | Alexandrina Victoria | Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

| Governors of New South Wales: Sir George Gipps, Sir Charles FitzRoy, Sir William Denison, Sir John Young, Somerset Lowry-Corry, 4th Earl Belmore, Sir Hercules Robinson, Lord Augustus Loftus, Charles Wynn-Carington, 3rd Baron Carrington, Victor Child Villiers, 7th Earl of Jersey, Sir Robert Duff, Henry Brand, 2nd Viscount Hampden, William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp Governors of Western Australia: Sir James Stirling, John Hutt, Sir Andrew Clarke, Charles Fitzgerald, Sir Arthur Kennedy, John Hampton, Sir Benjamin Pine, Sir Frederick Weld, Sir William Robinson, Sir Harry Ord, Sir Frederick Broome, Sir Gerard Smith Governors of South Australia: George Gawler, Sir George Grey, Frederick Robe, Sir Henry Young, Sir Richard MacDonnell, Sir Dominick Daly, Sir James Fergusson, Sir Anthony Musgrave, Sir William Jervois, Sir William Robinson, Algernon Keith-Falconer, 9th Earl of Kintore, Sir Thomas Buxton, Hallam Tennyson, 2nd Baron Tennyson Governors of Victoria: Sir Charles Hotham, Sir Henry Barkly, Sir Charles Darling, John Manners-Sutton, 3rd Viscount Canterbury, Sir Sir George Bowen, George Phipps, 2nd Marquess of Normanby, Sir Henry Loch, John Hope, 7th Earl of Hopetoun, Thomas Brassey, 1st Earl Brassey Governors of Tasmania: Sir Henry Young, Sir Thomas Browne, Sir Charles Du Cane, Sir Frederick Weld, Sir John Lefroy, Sir George Strahan, Sir Robert Hamilton, Jenico Preston, 14th Viscount Gormanston Governors of Queensland: Sir George Bowen, Samuel Blackall, George Phipps, 2nd Marquess of Normanby, Sir William Cairns, Sir Arthur Kennedy, Sir Anthony Musgrave, Sir Henry Norman, Charles Cochrane-Baillie, 2nd Baron Lamington Governor-general: John Hope, 7th Earl of Hopetoun Prime minister: Edmund Barton | ||||||

| 5 |

|

Edward VII (1841–1910) House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

22 January 1901 | 6 May 1910 | Albert Edward | Alexandra of Denmark |

| Governors-general: John Hope, 7th Earl of Hopetoun, Hallam Tennyson, 2nd Baron Tennyson, Henry Northcote, 1st Baron Northcote, William Ward, 2nd Earl of Dudley Prime ministers: Sir Edmund Barton, Alfred Deakin, Chris Watson, George Reid, Alfred Deakin, Andrew Fisher, Alfred Deakin | ||||||

| 6 |

|

George V (1865–1936) House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha until 1917 House of Windsor after 1917 |

6 May 1910 | 20 January 1936 | George Frederick Ernest Albert | Mary of Teck |

| Governors-general: William Ward, 2nd Earl of Dudley, Thomas Denman, 3rd Baron Denman, Sir Ronald Ferguson, Henry Forster, 1st Baron Forster, John Baird, 1st Baron Stonehaven. Sir Isaac Isaacs Prime ministers: Andrew Fisher, Joseph Cook, Andrew Fisher, Billy Hughes, Stanley Bruce, James Scullin, Joseph Lyons | ||||||

| 7 |

|

Edward VIII (1894–1972) House of Windsor |

20 January 1936 | 11 December 1936 | Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David | none |

| Governors-general: Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs, Alexander Hore-Ruthven, 1st Earl of Gowrie Prime ministers: Joseph Lyons | ||||||

| 8 |

|

George VI (1895–1952) House of Windsor |

11 December 1936 | 6 February 1952 | Albert Frederick Arthur George | Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon |

| Governors-general: Alexander Hore-Ruthven, 1st Earl of Gowrie, Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, Sir William McKell Prime ministers: Joseph Lyons, Sir Earle Page, Robert Menzies, Arthur Fadden, John Curtin, Frank Forde, Ben Chifley, Sir Robert Menzies | ||||||

| 9 |

|

Elizabeth II (1926–) House of Windsor |

6 February 1952 | Incumbent | Elizabeth Alexandra Mary | Philip Mountbatten |

| Governors-general: Sir William McKell, Sir William Slim, William Morrison, 1st Viscount Dunrossil, William Sidney, 1st Viscount De L'Isle, Richard Casey, Baron Casey, Sir Paul Hasluck, Sir John Kerr, Sir Zelman Cowen, Sir Ninian Stephen, William Hayden, Sir William Deane, Peter Hollingworth, Michael Jeffery, Dame Quentin Bryce, Sir Peter Cosgrove, David Hurley Prime ministers: Sir Robert Menzies, Harold Holt, John McEwen, John Gorton, William McMahon, Gough Whitlam, Malcolm Fraser, Bob Hawke, Paul Keating, John Howard, Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard, Kevin Rudd, Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull, Scott Morrison | ||||||

Timeline of monarchs since Federation[]

See also[]

- Succession to the Australian throne

- States headed by Elizabeth II

- Prime Ministers of Queen Elizabeth II

- List of Commonwealth visits made by Queen Elizabeth II

- List of Australian organisations with royal patronage

- Peerage of the Commonwealth of Australia

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Royal Style and Titles Act 1973 (Cth)". Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ Constitution section 2.

- ^ Letters Patent Relating to the Office of Governor‑General of the Commonwealth of Australia, 21 August 1984 "Office of Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia – 21/08/1984". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia: Letters Patent Relating to the Office of Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia: Amendment of Letters Patent Archived 20 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Williams, George; Brennan, Sean; Lynch, Andrew (2014). Blackshield and Williams Australian Constitutional Law and Theory (6 ed.). Annandale, NSW: Federation Press. pp. 352–65. ISBN 978-1-86287-918-8.

- ^ This is the effect of covering clause 2 of "Commonwealth of Australia Act 1900 (UK)". Federal Register of Legislation. "The provisions of this Act referring to the Queen shall extend to Her Majesty's heirs and successors in the sovereignty of the United Kingdom". The act contains the Constitution of Australia.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Government and Politics in Australia, 10th edition, by Alan Fenna and others, P.Ed Australia, 2013. Chapter 2, headnote, p.12 and Note 2 p.29.

- ^ Trepanier, Peter (2004). "Some Visual Aspects of the Monarchical Tradition" (PDF). Canadian Parliamentary Review. Ottawa: Commonwealth Parliamentary Association. 27 (2): 28. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sue v Hill [1999] HCA 30, (1999) 199 CLR 462 (23 June 1999), High Court (Australia).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Report of the Republic Advisory Committee, Commonwealth Government Printer, Canberra, 1993, p29-30

- ^ Twomey, Anne (2000). "Sue v Hill – The Evolution of Australian Independence". In Stone, Adrienne; Williams, George (eds.). The High Court at the crossroads: essays in constitutional law. New South Wales, Australia: Federation Press. ISBN 978-1-86287-371-1.

- ^ Constitution (Cth) s 51.

- ^ Re Patterson; Ex parte Taylor [2001] HCA 51, (2001) 207 CLR 391, High Court (Australia).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Prince, P. "We are Australian-The Constitution and Deportation of Australian-born Children". Research Paper no. 3 2003/04. Australian Parliamentary Library. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016.

- ^ Documents on Canadian External Relations; Volume No. 15 – 2; Chapter 1, Part 2, Royal Style and Titles

- ^ Documents on Canadian External Relations; Volume No. 18 – 2; Chapter 1, Part 2, Royal Style and Titles Archived 16 September 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b Royal Style and Titles Act 1953 (Cth).

- ^ Davidson, Helen (7 April 2018). "Royal visit flight costs could top $100,000 for Australian taxpayers". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ "Royal rates: What you'll pay for Will and Kate's Aussie adventure". 6 March 2014.

- ^ The Form and Order of Service that is to be performed and the Ceremonies that are to be observed in the Coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in the Abbey Church of St. Peter, Westminster, on Tuesday, the second day of June 1953 Archived 7 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Oremus.org (11 April 1994).

- ^ "Oaths and affirmations made by the executive and members of federal parliament since 1901". Parliament of Australia. 3 June 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ^ Constitution (Cth) s 2. Section 2 refers to "the Queen" (at the time, Queen Victoria) and covering clause 2 requires that to be interpreted as referring eventually to whoever of her "heirs and successors" is "in the sovereignty", i.e. is the monarch, of the United Kingdom.

- ^ Parliament House, Info Sheet 20 The Australian system of government Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Constitution (2012) Overview by the Attorney-General's Department and Australian Government Solicitor "The Constitution". Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Alan Fenna; Jane Robbins; John Summers (5 September 2013). Government Politics in Australia. Pearson Higher Education AU. pp. 21–23. ISBN 978-1-4860-0138-5.

- ^ Australia's Head of State, Australians for Constitutional Monarchy, Accessed=1 March 2016 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ [url=http://www.republic.org.au Australian Republic Movement website]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams, George; Brennan, Sean & Lynch, Andrew (2014). Blackshield and Williams Australian Constitutional Law and Theory (6 ed.). Leichhardt, NSW: Federation Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-86287-918-8.

- ^ Governor General of the Commonwealth of Australia: Transcript – World Today with Major General Jeffery – 23 June 2003 Archived 2 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade: Negotiating and Implementing Treaties Archived 31 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade: Treaties, the Constitution and the National Interest Archived 31 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Australian Constitution section 5 Archived 11 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Australian Constitution s 59 Archived 11 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gibbs, Harry; ''The Crown and the High Court – Celebrating the 100th birthday of the High Court of Australia''; 17 October 2003 Archived 27 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Norepublic.com.au (17 October 2003).

- ^ The Queen as Fount of Justice. Royal.gov.uk (17 December 2013). Archived 17 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Essenberg v The Queen B55/1999 [2000] HCATrans 386, High Court (Australia).

- ^ The Queen v Tang [2008] HCA 39, (2008) 237 CLR 1, High Court (Australia).

- ^ Section 475(1) Crimes Act 1900 (ACT); ss 474B and 474C Crimes Act 1900 and s 26 Criminal Appeal Act 1912 (NSW); s 433A Criminal Code (Northern Territory); ss 669A, 672A Criminal Code 1899 (Queensland); s 369 Criminal Law Consolidation Act 1935 (South Australia); ss 398, 419 Criminal Code (Tasmania); s 584 Crimes Act 1958 (Victoria); s 21 Criminal Code and Part 19 Sentencing Act 1995 (Western Australia)

- ^ Buckingham Palace: Guidelines and Procedures for the Acceptance, Classification, Retention and Disposal of Gifts to Members of the Royal Family. Royal.gov.uk (22 August 2012). Archived 14 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bushfires memorial echoes grief and hope – "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Princess Anne in bushfire tribute – "Princess Anne in bushfire tribute". 22 February 2009. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- ^ The Queen's message following the fires in Australia. Royal.gov.uk. Archived 15 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Princess Royal to visit areas affected by the Victorian bushfires. Royal.gov.uk. Archived 24 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Church of England Australia was organised on the basis that it was part of the Church of England, not merely 'in communion with', or 'in connection with', the Church of England. Thus any changes to doctrine or practice in England were to be applied in Australia, unless the local situation made the change inapplicable. ... A new national constitution was agreed in 1961 and came into force on 1 January 1962. This created a new church, the Church of England in Australia, and severed the legal nexus with the Church of England." Outline of the Structure of the Anglican Church of Australia, p. 5.

- ^ Part 2 – The Anglican Church in Australia Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Anglican Church of Australia. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ "The Governor-General's Official residences". . Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Raspal Khosa (2004). Australian Defence Almanac 2004–05. Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra. Page 4.

- ^ "RAR; the Royal Australian Regiment; a history". Archived from the original on 9 September 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Mlahanas.de.

- ^ Queen and Commonwealth: Australia: History. Royal.gov.uk (22 August 2012). Archived 11 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Day, D; Claiming a Continent; Harper Collins, 1997; p.38

- ^ B. Hunter (ed) The Statesman's Year Book, MacMillan Press, p.102 ff.

- ^ Craig, John; Australian Politics: A Source Book; second ed.; p.43

- ^ W.J. Hudson and M.P. Sharp, Australian Independence, pp. 4, 90

- ^ E.M. Andrews, The ANZAC Illusion, p.21

- ^ David Smith, Head of State, Macleay Press 2005, p.24

- ^ Statute of Westminster 1931 (c. 4) s. 4 Archived 4 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine; cf McInn, W.G.; A Constitutional History of Australia; p.152

- ^ Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942 (Cth) s 3 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Craig, John; Australian Politics: A Source Book; p.43

- ^ Biography – first Duke of Gloucester – Australian Dictionary of Biography. Adbonline.anu.edu.au.

- ^ Magnay, Jacquelin (27 January 2011). "Prince Charles says 'Pommy' insults were character building". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ "Prince Harry arrives for gap year in Australia". BBC News. 23 September 2003.

- ^ Craig; p.43

- ^ Chipp, Don; An Individual View; p.144

- ^ Newspoll polls 1995–2002, The Australian Archived 15 June 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Paul Keating: republicanism, People and power, Power, people and politics in the post-war period, History Year 9, NSW | Online Education Home Schooling Skwirk Australia Archived 15 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Skwirk.com (1 January 2001).

- ^ Kevin Rudd reaffirms support for republic | PerthNow Archived 11 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. News.com.au (6 April 2008).

- ^ Speech by Prime Minister of Australia, Julia Gillard, 21 October 2011, Parliament House

- ^ Address to a Reception for Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Parliament House – Office of Tony Abbott, Leader of the Opposition, 21 October 2011

- ^ "Republic floats away as royal reign lingers" by Judith Ireland, The Canberra Times, 22 October 2011.

- ^ Mansillo, Luke (25 January 2016). "Loyal to the Crown: shifting public opinion towards the monarchy in Australia". Australian Journal of Political Science. 51 (2): 213–235. doi:10.1080/10361146.2015.1123674.

- ^ "Monarchy support at highest level: Poll".

- ^ Wood, Miranda (12 July 2020). "Poll finds majority want an Australian head of state". The Sunday Telegraph. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

References[]

- ^ National Archives of Australia: King George VI (1936–52)

- ^ National Museum of Australia: Royal Romance

- ^ National Archives of Australia: Royal Visit 1954

- ^ National Archives of Australia: Royal Visit 1963

- ^ National Archives of Australia: Prince Charles

- ^ Australian Government: Royal Visits to Australia

- ^ National Archives of Australia: Royalty and Australian Society

- ^ Yahoo News: Prince Edward to visit Vic fire victims[dead link]

- ^ ABC News: Royal couple set for busy Aust schedule

- ^ Queen, Howard honour war dead

- ^ World leaders hail D-Day veterans

Bibliography[]

- Hill, David (2016). Australia and the Monarchy. Random House. ISBN 978-0857987549.

- Smith, David (2005). Head of State: the Governor-General, the Monarchy, the Republic and the Dismissal. Paddington, NSW: Macleay Press. ISBN 978-1876492151.

- Twomey, Anne (2006). The Chameleon Crown: the Queen and her Australian Governors. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press. ISBN 9781862876293.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Australian monarchy. |

- Commonwealth realms

- Australian constitutional law

- Monarchy in Australia