History of Indigenous Australians

The history of Indigenous Australians began at least 65,000 years ago when humans first populated the Australian continental landmasses.[1] This article covers the history of Aboriginal Australian and Torres Strait Islander peoples, two broadly defined groups which each include other sub-groups defined by language and culture.

The origin of the first humans to populate the southern continent and the pieces of land which became islands as ice receded and sea levels rose remains a matter of conjecture and debate. Some anthropologists believe they could have arrived as a result of the earliest human migrations out of Africa. Although they likely migrated to the territory later named Australia through Southeast Asia, Aboriginal Australians are not demonstrably related to any known Asian or Melanesian population, although Torres Strait Islander people do have a genetic link to some Melanesian populations. There is evidence of genetic and linguistic interchange between Australians in the far north and the Austronesian peoples of modern-day New Guinea and the islands, but this may be the result of recent trade and intermarriage.[2]

Estimates of the number of people living in Australia at the time that colonisation began in 1788, who belonged to a range of diverse groups, vary from 300,000 to a million,[3] and upper estimates place the total population as high as 1.25 million.[4] A cumulative population of 1.6 billion people has been estimated to have lived in Australia over 65,000 years prior to British colonisation.[5] The regions of heaviest Aboriginal population were the same temperate coastal regions that are currently the most heavily populated, the Murray River valley in particular. In the early 1900s it was commonly believed that the Aboriginal population of Australia was leading toward extinction. The population shrank from those present when colonisation began in New South Wales in 1788, to 50,000 in 1930. This drastic reduction in numbers has been attributed to outbreaks of smallpox and other diseases to which the Indigenous peoples had no immunity,[6][7] but other sources have described the extent of frontier clashes and in some cases, deliberate killings of Aboriginal peoples.[8]

Post-colonisation, the coastal Indigenous populations were soon absorbed, exterminated,[9] depleted or forced from their lands; the traditional aspects of Aboriginal life which remained persisted most strongly in areas such as the Great Sandy Desert where European settlement has been sparse. Although the Aboriginal Tasmanians were almost driven to extinction (and once thought to be so), other Aboriginal Australian peoples maintained successful communities throughout Australia.

Migration to Australia[]

It is believed that early human migration to Australia was achieved when it formed part of the Sahul continent, connected to the island of New Guinea via a land bridge.[10] This would have nevertheless required crossing the sea at the so-called Wallace Line.[11] It is also possible that people came by island-hopping via an island chain between Sulawesi and New Guinea, reaching North Western Australia via Timor.[12]

A 2021 study which mapped likely migration routes suggests that the populating of the Sahul took 5,000–6,000 years to reach Tasmania (then part of the continent),[13] with a rate of one kilometre per year,[14] after making landfall in the Kimberley region of Western Australia around 60,000 years ago.[13] The total human population could have been as high as 6.4 million, with 3 million in the area of modern Australia.[14] The modelling suggests that the path of population movement may have followed two main routes down from contemporary New Guinea, with the so-called "southern route" going into Kimberley, Pilbara and Arnhem Land, and then to the Great Sandy Desert before moving towards the centre in Lake Eyre and further on to the southeast of the continent. It also leads through another path to the southwestern parts, such as Margaret River and the Nullarbor Plain. The "northern route" meanwhile crosses over the current location of the Torres Strait and then divides into one path connecting to Arnhem Land and another leading down the East Coast.[15] The routes are similar to current highways and stock routes in Australia. [13]

Madjedbebe is the oldest known site showing the presence of humans in Australia, with evidence suggesting that it was first occupied by humans possibly by 65,000 ± 6,000 years ago and at least by 50,000 years ago.[16][17] The rock shelters at Madjedbebe (about 50 kilometres (31 mi) inland from the present coast)[18] and at (70 kilometres (43 mi) further south) show evidence of used pieces of ochre used by artists 60,000 years ago. Near Penrith, stone tools have been found in Cranebrook Terraces gravel sediments having dates of 45,000 to 50,000 years BP.[19][20] A 48,000 BCE date is based on a few sites in northern Australia dated using thermoluminescence. Charles Dortch dated finds on Rottnest Island, Western Australia at 70,000 years BP in 1994.[21][needs update] There is also evidence of a change in fire régimes in Australia, drawn from reef deposits in Queensland, between 70–100,000 years ago,[22] and the integration of human genomic evidence from various parts of the world also supports a date of before 60,000 years for the arrival of Australian Aboriginal people in the continent.[23][24][25]

Humans reached Tasmania approximately 40,000 years ago by migrating across a land bridge from the mainland that existed during the last glacial maximum. After the seas rose about 12,000 years ago and covered the land bridge, the inhabitants there were isolated from the mainland until the arrival of European settlers.[26]

Short-statured Aboriginal tribes inhabited the rainforests of North Queensland, of which the best known group is probably the Tjapukai of the Cairns area.[27] These rainforest people, collectively referred to as Barrineans, were once considered to be a relic of an earlier wave of Negrito migration to the Australian continent,[28] but this "Aboriginal pygmy" theory has been discredited.[29]

Mungo Man, found near Lake Mungo in New South Wales, is the oldest human yet found in Australia. Although the exact age of Mungo Man is in dispute, the best consensus is that he is at least 40,000 years old. Stone tools also found at Lake Mungo have been estimated, based on stratigraphic association, to be about 50,000 years old. Since Lake Mungo is in south-eastern Australia, many archaeologists have concluded that humans must have arrived in north-west Australia at least several thousand years earlier.

Changes around 4,000 years ago[]

The dingo reached Australia about 4,000 years ago, and around the same time there were changes in language, with the Pama-Nyungan language family spreading over most of the mainland, and stone tool technology, with the use of smaller tools. Human contact has thus been inferred, and genetic data of two kinds have been proposed to support a gene flow from India to Australia: firstly, signs of South Asian components in Aboriginal Australian genomes, reported on the basis of genome-wide SNP data; and secondly, the existence of a Y chromosome (male) lineage, designated haplogroup C∗, with the most recent common ancestor around 5,000 years ago.[30]

A 2013 study by researchers at the Max Planck Institute led by Irina Pugach, the result of large-scale genotyping, indicated that Aboriginal Australians, the indigenous peoples of New Guinea and the Mamanwa, an indigenous people of the southern Philippines are closely related, having diverged from a common origin approximately 36,000 years ago. The same study shows that Aboriginal genomes consist of up to 11% Indian DNA which is uniformly spread through Northern Australia, indicating a substantial gene flow between Indian populations and Northern Australia occurred around 4,230 years ago. Changes in tool technology and food processing appear in the archaeological record around this time, suggesting there may have been migration from India.[31][32]

However, a 2016 study in Current Biology by Anders Bergström et al. excluded the Y chromosome as providing evidence for recent gene flow from India into Australia. The study authors sequenced 13 Aboriginal Australian Y chromosomes using recent advances in gene sequencing technology, investigating their divergence times from Y chromosomes in other continents, including comparing the haplogroup C chromosomes. The authors concluded that, although this does not disprove the presence of any Holocene gene flow or non-genetic influences from South Asia at that time, and the appearance of the dingo does provide strong evidence for external contacts, the evidence overall is consistent with a complete lack of gene flow, and points to indigenous origins for the technological and linguistic changes. Gene flow across the island-dotted 150-kilometre (93 mi)-wide Torres Strait, is both geographically plausible and demonstrated by the data, although at this point it could not be determined from this study when within the last 10,000 years it may have occurred – newer analytical techniques have the potential to address such questions.[30]

Early history[]

Geography[]

When the north-west of Australia, which is closest to Asia, was first occupied, the region consisted of open tropical forests and woodlands. After around 10,000 years of stable climatic conditions, by which time the Aboriginal people had settled the entire continent, temperatures began cooling and winds became stronger, leading to the beginning of an ice age. By the glacial maximum, 25,000 to 15,000 years ago, the sea level had dropped to around 140 metres below its present level. Australia was connected to New Guinea and the Kimberley region of Western Australia was separated from Southeast Asia (Wallacea) by a strait only approximately 90 km wide.[33] Rainfall was 40% to 50% lower than modern levels, depending on region, while the lower CO2 levels (half pre-industrial levels) meant that vegetation required twice as much water for photosynthesis.[34]

The Kimberley, including the adjacent exposed continental Sahul Shelf, was covered by vast grasslands dominated by flowering plants of the family Poaceae, with woodlands and semi-arid scrub covering the shelf joining New Guinea to Australia.[35] Southeast of the Kimberley, from the Gulf of Carpentaria to northern Tasmania the land, including the western and southern margins of the now exposed continental shelves, was covered largely by extreme deserts and sand dunes. It is believed that during this period no more than 15% of Australia supported trees of any kind. While some tree cover remained in the southeast of Australia, the vegetation of the wetter coastal areas in this region was semi-arid savanna, while some tropical rainforests survived in isolated coastal areas of Queensland.

Tasmania was covered primarily by cold steppe and alpine grasslands, with snow pines at lower altitudes. There is evidence that there may have been a significant reduction in Australian Aboriginal populations during this time, and there would seem to have been scattered "refugia" in which the modern vegetation types and Aboriginal populations were able to survive. Corridors between these refugia seem to be routes by which people kept in contact.[36][37][38] With the end of the ice age, strong rains returned, until around 5,500 years ago, when the wet season cycle in the north ended, bringing with it a megadrought that lasted 1,500 years. The return of reliable rains around 4,000 years BP gave Australia its current climate.[35]

Following the Ice Age, Aboriginal people around the coast, from Arnhem Land, the Kimberley and the southwest of Western Australia, all tell stories of former territories that were drowned beneath the sea with the rising coastlines after the Ice Age. It was this event that isolated the Tasmanian Aboriginal people on their island, and probably led to the extinction of Aboriginal cultures on the Bass Strait Islands and Kangaroo Island in South Australia.[39] In the interior, the end of the Ice Age may have led to the recolonisation of the desert and semi-desert areas by Aboriginal people of the Northern Territory. This in part may have been responsible for the spread of languages of the Pama–Nyungan language family and secondarily responsible for the spread of male initiation rites involving circumcision. There has been a long history of contact between Papuan peoples of the Western Province, Torres Strait Islanders and the Aboriginal people in Cape York.[39]

The Aboriginal Australians lived through great climatic changes and adapted successfully to their changing physical environment. There is much ongoing debate about the degree to which they modified the environment. One controversy revolves around the role of indigenous people in the extinction of the marsupial megafauna (also see Australian megafauna). Some argue that natural climate change killed the megafauna. Others claim that, because the megafauna were large and slow, they were easy prey for human hunters. A third possibility is that human modification of the environment, particularly through the use of fire, indirectly led to their extinction.[citation needed]

Oral history demonstrates "the continuity of culture of Indigenous Australians" for at least 10,000 years. This is shown by correlation of oral history stories with verifiable incidents including known changes in sea levels and their associated large changes in location of ocean shorelines; oral records of megafauna; and comets.[40][41]

Ecology[]

The introduction of the dingo, possibly as early as 3500 BCE, showed that contact with South East Asian peoples continued, as the closest genetic connection to the dingo seems to be the wild dogs of Thailand. This contact was not just one-way, as the presence of kangaroo ticks on these dogs demonstrates. Dingoes began and evolved in Asia. The earliest known dingo-like fossils are from Ban Chiang in north-east Thailand (dated at 5500 years BP) and from north Vietnam (5000 years BP). According to skull morphology, these fossils occupy a place between Asian wolves (prime candidates were the pale footed (or Indian) wolf Canis lupus pallipes and the Arabian wolf Canis lupus arabs) and modern dingoes in Australia and Thailand.[42]

Most scientists presently believe that it was the arrival of the Australian Aboriginal people on the continent and their introduction of fire-stick farming that was responsible for these extinctions.[43] Fossil research published in 2017 indicates that Aboriginal people and megafauna coexisted for "at least 17,000 years". Aboriginal Australians used fire for a variety of purposes: to encourage the growth of edible plants and fodder for prey; to reduce the risk of catastrophic bushfires; to make travel easier; to eliminate pests; for ceremonial purposes; for warfare and just to "clean up country." There is disagreement, however, about the extent to which this burning led to large-scale changes in vegetation patterns.[44]

Food[]

Aboriginal Australians were limited to the range of foods occurring naturally in their area, but they knew exactly when, where and how to find everything edible. Anthropologists and nutrition experts who have studied the tribal diet in Arnhem Land found it to be well-balanced, with most of the nutrients modern dietitians recommend. But food was not obtained without effort. In some areas both men and women had to spend from half to two-thirds of each day hunting or foraging for food. Each day, the women of the group went into successive parts of one countryside with wooden digging sticks and plaited dilly bags or wooden coolamons. Larger animals and birds, such as kangaroos and emus, were speared or disabled with a thrown club, boomerang, or stone. Many Indigenous hunting devices were used to get within striking distance of prey. The men were excellent trackers and stalkers, approaching their prey running where there was cover, or 'freezing' and crawling when in the open. They were careful to stay downwind and sometimes covered themselves with mud to disguise their smell.

Fish were sometimes taken by hand by stirring up the muddy bottom of a pool until they rose to the surface, or by placing the crushed leaves of poisonous plants in the water to stupefy them. Fish spears, nets, wicker or stone traps were also used in different areas. Lines with hooks made from bone, shell, wood or spines were used along the north and east coasts. Dugong, turtle and large fish were harpooned, the harpooner launching himself bodily from the canoe to give added weight to the thrust. Both Torres Strait Island populations and mainland aborigines were agriculturalists who supplemented their diet through the acquisition of wild foods.[45] Aboriginal Australians along the coast and rivers were also expert fishermen. Some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people relied on the dingo as a companion animal, using it to assist with hunting and for warmth on cold nights.

In present-day Victoria, for example, there were two separate communities with an economy based on eel-farming in complex and extensive irrigated pond systems; one on the Murray River in the state's north, the other in the south-west near Hamilton in the territory of the Djab Wurrung, which traded with other groups from as far away as the Melbourne area (see Gunditjmara). A primary tool used in hunting is the spear, launched by a woomera or spear-thrower in some locales. Boomerangs were also used by some mainland Indigenous Australians. The non-returnable boomerang (known more correctly as a Throwing Stick), more powerful than the returning kind, could be used to injure or even kill a kangaroo.

On mainland Australia no animal other than the dingo and the Short-finned eel were domesticated, however domestic pigs and cassowaries were utilised by Torres Strait Islanders.[46] The typical Aboriginal diet included a wide variety of foods, such as pig, kangaroo, emu, wombats, goanna, snakes, birds, many insects such as honey ants, Bogong moths and witchetty grubs. Many varieties of plant foods such as taro, coconuts, nuts, fruits and berries were also eaten.

Banana cultivation is now known to have been present among Torres Strait Islanders.[47]

Culture[]

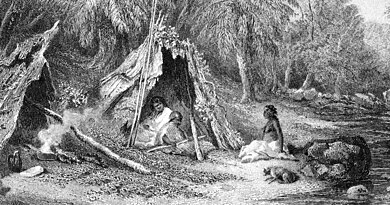

Permanent villages were the norm for most Torres Strait Island communities. In some areas mainland Aboriginal Australians also lived in semi-permanent villages, most usually in less arid areas where fishing and agriculture[48] could provide for a settled existence, with places like Budj Bim in particular growing to comparatvely large settlements. Most Indigenous communities were semi-nomadic, moving in a regular cycle over a defined territory, following seasonal food sources and returning to the same places at the same time each year. From the examination of middens, archaeologists have shown that some localities were visited annually by Indigenous communities for thousands of years. In the more arid areas Aboriginal Australians were nomadic, ranging over wide areas in search of scarce food resources. There is evidence of substantial change in indigenous culture over time. Rock painting at several locations in northern Australia has been shown to consist of a sequence of different styles linked to different historical periods. There is also prominent rock paintings found in the Sydney basin area which date to around 5,000 years.

Harry Lourandos has been the leading proponent of the theory that a period of agricultural intensification occurred between 3000 and 1000 BCE. Intensification involved an increase in human manipulation of the environment (for example, the construction of eel traps in Victoria), population growth, an increase in trade between groups, a more elaborate social structure, and other cultural changes. A shift in stone tool technology, involving the development of smaller and more intricate points and scrapers, occurred around this time. This was probably also associated with the introduction to the mainland of the Australian dingo.

Many Indigenous communities also have a very complex kinship structure and in some places strict rules about marriage. In traditional societies, men are required to marry women of a specific moiety. The system is still alive in many Central Australian communities. To enable men and women to find suitable partners, many groups would come together for annual gatherings (commonly known as corroborees) at which goods were traded, news exchanged, and marriages arranged amid appropriate ceremonies. This practice both reinforced clan relationships and prevented inbreeding in a society based on small semi-nomadic groups.

1770–1850s: impact of British colonisation[]

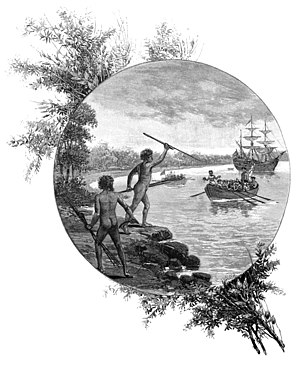

The first contact between British explorers and Indigenous Australians came in 1770, when Lieutenant James Cook interacted with the Guugu Yimithirr people around contemporary Cooktown. Cook wrote that he had claimed the east coast of Australia for what was then the Kingdom of Great Britain and named it New South Wales, while on Possession Island off the west coast of Cape York Peninsula.[49] However, it seems that no such claim was made when Cook was in Australia.[50] Cook's orders were to look for "a Continent or Land of great extent" and "with the Consent of the Natives to take possession of Convenient situations in the Country in the name of the King".[51] The British government did not view Aboriginal Australians as the owners of the land as they did not practise farming.[52] British colonisation of Australia began at Port Jackson in 1788 with the arrival of Governor Phillip and the First Fleet.[53] The Governor was instructed to "by every possible means to open an intercourse with the natives, and to conciliate their affections, enjoining all our subjects to live in amity and kindness with them" and to punish those aiming to "wantonly destroy them".[54]

The immediate reaction of the Eora, who were first to witness it, to colonisation was at first surprise and then aggression.[55] Following this the Eora generally avoided the British for the next two years.[56] They were offended by the British entering their lands and taking advantage of their resources without asking permission, as was customary in Aboriginal society.[54] Some contacts did however occur, with both the Eora and the Tharawal at Botany Bay, including exchanges of gifts.[56] Out of the 17 encounters during the first month, only two involved the Eora entering British settlements.[56] After a year, Phillip decided to capture Indigenous people to teach them English and make them intermediaries, resulting in the kidnappings of Arabanoo and Bennelong, with Phillip getting speared by latter's companion.[54] Bennelong would eventually travel to England with Phillip and Yemmerrawanne in 1793.[57] A Kuringgai man Bungaree also made voyages with Europeans.[57] Following the lethal spearing of a huntsman, possibly by Pemulwuy, Phillip ordered 10 men (but not women or children) in Botany Bay to be captured and beheaded.[58] None were however found.[58]

The first apparent consequence of British settlement appeared in April 1789 when a disease, which was probably smallpox, struck the Aborigines about Port Jackson.[59] Before the epidemic, the First Fleet had equalled the population of the Eora; after it the settler population was equal to all Indigenous people on the Cumberland Plain; and by 1820, their population of 30,000 was as much of the entire Indigenous populace of New South Wales.[60] A generation after colonization, the Eora, Dharug and Kuringgai had been greatly reduced and were mainly living in the outskirts of European society, though some Indigenous people did continue to live in the coastal regions around Sydney further on, as well as around Georges River and Botany Bay.[61] Further inland, Indigenous peoples were warned of the British invasion after the Cumberland Plain had been taken by 1815, and this information preceded them by hundreds of kilometres.[62] However, by the second generation of contact, many groups in south-eastern Australia were gone.[63] The greatest cause of death was disease, followed by settler and inter-Indigenous killings.[63] This population loss was further exacerbated by an extremely low birth rate.[64] An estimated decline of 80 percent in the population meant that traditional kinship systems and ceremonial obligations became hard to maintain and family and social relations were torn.[65] The survivors came to live on the fringes of European society, living in tents and shacks around towns and riverbanks in poor health.[66]

Aboriginal Tasmanians first came to contact with Europeans when the Baudin expedition to Australia arrived at Adventure Bay in 1802.[67] The French explorers were more friendly to the Indigenous than the British further north.[67] Already earlier, in 1800, European whalers had been to the Bass Strait islands, were they had used kidnapped aboriginal women.[67] The local Indigenous also sold women to the sailors.[68] Later the descendants of these women would be the last survivors of Tasmanian Indigenous people.[63]

Assimilation[]

The assimilation policy was first started by Governor Macquarie, who established in 1814 the Native Institution in Blacktown "to effect the Civilization of the Aborigines of New South Wales, and to render their Habits more domesticated and industrious" by enrolling children in a residential school.[69] By 1817, 17 were enrolled, one of whom, a girl called Maria, won the first prize in a school exam ahead of European children in 1819.[69] The institution was however closed soon after following Macquarie's replacement for spending.[70] Macquerie also had attempted to settle 16 Kuringgai at George's Head with land, pre-fabricated huts and other supplies, but the families had soon sold the farms and left.[70]

Christian missions were also started at Lake Macquarie in 1827, at Wellington Valley in 1832, and in Port Phillip and Moreton Bay around 1840.[70] These involved learning Indigenous languages, with the Gospel of Luke translated into Awabakal in 1831 by a missionary and Biraban, as well as offering food and sanctuary on the frontier.[71] However, when supplies ran out, the Indigenous would often leave for pastoral stations in search of work.[71] Some missionaries would take children without consent to be taught in dormitories.[72]

The government had started blanket distribution in the 1830s, but ended this in 1844 as a cost-saving measure.[74] It also created Indigenous paramilitary units, called the Australian native police, with these being establish in Port Phillip in 1842, New South Wales in 1848, and in Queensland 1859.[75] Exceptional among these, the Port Phillip force had police powers over white people as well.[76] The forces killed hundreds of (or in the case of Queensland, up to a thousand) Indigenous people.[77]

In 1833, A committee of the British House of Commons, led by Fowell Buxton demanded better treatment of the Indigenous, referring to them as 'original owners', leading the British government in 1838 to create the office of the Protector of Aborigines.[78] However, this effort ended by 1857.[78] Nevertheless, the humanitarian effort did produce the Waste Land Act of 1848, which gave indigenous people certain rights and reserves on the land.[79]

There was also some assimilation of settlers into Indigenous cultures. Living with Indigenous people was William Buckley, an escaped convict, who was with the Wautharong people near Melbourne for thirty-two years, before being found in 1835. Eliza Fraser was a Scottish woman who was aboard a ship that wrecked at an island off the coast of Queensland, Australia, on 22 May 1836, and who was taken in by the Badtjala (Butchella) people. James Morrill was an English sailor aboard the vessel Peruvian which became shipwrecked off the coast of north-eastern Australia in 1846, was taken in by a local clan of Aboriginal Australians. He adopted their language and customs and lived as a member of their society for 17 years. Indigenous peoples also adopted the European dog widely.[80]

Conflict[]

On the mainland, prolonged conflict followed the frontier of European settlement.[81] A minimum of 40,000 Indigenous Australians and between 2,000 and 2,500 settlers died in the wars. However, recent scholarship on the frontier wars in what is now the state of Queensland indicates that Indigenous fatalities may have been significantly higher. Indeed, while battles and massacres occurred in a number of locations across Australia, they were particularly bloody in Queensland, owing to its comparatively larger pre-contact Indigenous population. It is estimated that up to 3,000 white people were killed by Aboriginal Australians in the frontier violence.[82] Some Indigenous people also allied with the colonists against other Indigenous people.[83] Colonization accelerated fighting between Indigenous groups by causing them to leave their traditional lands as well as by causing deaths by disease which were attributed to enemy sorcery.[84] Indigenous gun ownership was banned in New South Wales in 1840, but this was overturned by the British government as inequality before the law.[85]

In 1790, an Aboriginal leader Pemulwuy in Sydney resisted the Europeans,[86] waging a guerrilla-style warfare on the settlers in a series of wars known as the Hawkesbury and Nepean Wars, which spanned 26 years, from 1790 to 1816.[87] After his death in 1802, his son Tedbury continued the campaign until 1810.[60] The campaign led to the banning of Aboriginal groups of more than six and forbid them from carrying weapons closer to two kilometers from settlements.[60] Beyond the Cumberland Plain, violence erupted first at Bathurst against the Wiradjuri, with martial law declared in 1822 and the 40th Regiment responding.[88] This became known as the Bathurst War.

In Van Diemen's Land, conflict arrived in 1824 after major expansion of settler and sheep numbers, with Indigenous warriors responding by killing 24 Europeans by 1826.[88] In 1828, martial law was declared and bounty parties of settlers took vengeance.[89] On the Indigenous side, Musquito led the Oyster Bay tribe against the settlers.[75] Tarenorerer was another leader. The Black War, fought largely as a guerrilla war by both sides, claimed the lives of 600 to 900 Aboriginal people and more than 200 European colonists, nearly annihilating the island's indigenous population.[90][91] The near-destruction of the Aboriginal Tasmanians, and the frequent incidence of mass killings, has sparked debate among historians over whether the Black War should be defined as an act of genocide.[92]

In Swan River Colony, conflict occurred near Perth, with the government offering the use of the armoury for the settlers.[83] A punitive party was led against the Pindjarup in 1834.[83]

Diseases[]

Deadly infectious diseases like smallpox, influenza and tuberculosis were always major causes of Aboriginal deaths.[93] Smallpox alone killed more than 50% of the Aboriginal population.[7] Other diseases included dysentery, scarlet fever, typhus, measles, whooping cough and influenza.[94] Sexually transmitted infections were also introduced by colonialism.[94] Health decline was also caused by increasing use of flour and sugar instead of more diverse traditional diets, resulting in malnutrition.[95] Alcohol was also first introduced by colonialism, leading to alcoholism.[96]

In April 1789, a major outbreak of smallpox killed large numbers of Indigenous Australians between Hawkesbury River, Broken Bay, and Port Hacking. Based on information recorded in the journals of some members of the First Fleet, it has been surmised that the Aborigines of the Sydney region had never encountered the disease before and lacked immunity to it. Unable to understand or counter the sickness, they often fled, leaving the sick with some food and water to fend for themselves. As the clans fled, the epidemic spread further along the coast and into the hinterland. This had a disastrous effect on Aboriginal society; with many of the productive hunters and gatherers dead, those who survived the initial outbreak began to starve.[citation needed]

Some have suggested that Makasar fishermen accidentally brought smallpox to Australia's north and the virus travelled south.[97] However, given that the spread of the disease depends on high population densities, and the fact that those who succumbed were soon incapable of walking, such an outbreak was unlikely to have spread across the desert trade routes.[98] A more likely source of the disease was the "variolas matter" Surgeon John White brought with him on the First Fleet, although it is unknown how this may have been spread.[98] It has also been speculated that the vials were either accidentally or intentionally released as a "biological weapon".[99] In 2014, writing in Journal of Australian Studies, Christopher Warren concluded that British marines were most likely to have spread smallpox, possibly without informing Governor Phillip, but conceded in his conclusion that "today's evidence only provides for a balancing of probabilities and this is all that can be attempted."[100]: 79, 68–86

Economy and environment[]

In 1822, the British government rediced duties on Australian wool, leading to an expansion of sheep numbers, followed by increased immigration.[101] The sheep flourished in the arid western plains.[102] The settlers created an ecological revolution, as their cattle ate away local grasses and trampled waterholes, with precious food staples like murnong diminished, and with new weeds spreading.[103] Meat sources like kangaroo and the Australian brushturkey were replaced by cattle.[104] In response, Indigenous peoples would appropriate settler resources, such as taking sheep and raising their own flocks.[104] New economic products also disrupted traditional lifestyles, as for example in the case of the steel axe, which replaced the traditional stone one, resulting in a loss of authority to the older men who traditionally had access to them.[105] The new axes would be given to younger people by settlers and missionaries in exchange for work, also diminishing old trading networks.[105]

Following the loss of lands, Indigenous people 'came in' to pastoral station, missions and towns, often forced by lack of food.[106] Tobacco, tea and sugar were also important in attracting Indigenous people to settlers.[107] After some handouts, work was demanded by the settlers in return for rations, leading to Indigenous employment in cutting timber, herding and shearing sheep, and in stock work.[108] They were also working as fishermen, water carriers, domestic servants, boatmen and whalers.[109] However, European work ethic was not part of their culture, as working beyond the amount necessary for future benefits was seen as not important.[110] Their pay was also unequal to that of settlers, being mostly rations or less than half the wage.[110] Women had previously been the main providers in Indigenous families, but their roles were diminished as men became the main recipients of wages and rations, while women could at most find European-style domestic work or prostitution, leading some to live with European men who had access to resources.[111]

1850s–1940s: northern colonization, racism, and resistance[]

By 1850, southern Australia had been settled by the British, except for the Great Victoria Desert, Nullarbor Plain, Simpson Desert, and Channel Country.[112] European explorers had started to venture into these areas, as well as the Top End and Cape York Peninsula.[112] By 1862 they had crossed the continent and entered Kimberley and Pilbara, while consolidating colonial claims in the process.[112] Indigenous reaction to them ranged from assistance to hostility.[112] Any new lands were claimed, mapped and opened to pastoralists, with North Queensland settled in the 1860s, Central Australia and the Northern Territory in the 1870s, Kimberley in the 1880s, and the Wunaamin Miliwundi Ranges after 1900.[112][113] This again led to violent confrontation with the Indigenous peoples.[112] However, because of the dryness and remoteness of the new frontier, settlement and economic development were slower.[114] The European population therefore remained small and consequently more fearful, with few police protecting the Indigenous population.[114] It is estimated that in North Queensland 15 percent of the first wave of pastoralists were killed in Indigenous attacks, while 10 times more of the other side met the same fate.[115] In the Gulf Country, over 400 violent Indigenous deaths were recorded 1872 to 1903.[116]

In the earlier settled southern parts of Australia, only 20,000 Indigenous individuals (10 percent of the total at the beginning of colonization), remained by the 1920s, with half being of mixed ancestry.[117] There about 7000 in New South Wales, 5000 in southern Queensland, 2500 in south-west Western Australia, 1000 in southern South Australia, 500 in Victoria, and under 200 in Tasmania (mostly on Cape Barren Island).[117] One fifth lived in reserves, while most of the rest were in camps around country towns, with small numbers owning farms or living in towns or capital cities.[117] In the country as a whole, there were about 60,000 Indigenous people in 1930.[118]

The Defence Act of 1903 only allowed those of "European origin or descent" to enlist in military service.[119] However, in 1914 around 800 Aboriginal people answered the call to arms to fight in World War I.[120] As the war continued, these restrictions were relaxed as more recruits were needed.[citation needed] Many enlisted by claiming they were Māori or Indian.[121] During World War II, after the threat of Japanese invasion of Australia, Indigenous enlistment was accepted.[122] Up to 3000 individuals of mixed descent served in the military, including Reg Saunders, the first indigenous officer.[123] The Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion, Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit, and the Snake Bay Patrol were also established. Another 3000 civilians worked in labour corps.[123]

Employment, wagelessness and resistance[]

Nevertheless, Indigenous workers in the north were able to find jobs better than in south since there was no cheap convict labour available, though they were not paid in wages and were abused.[124] There was a widely held belief that white people could not work in Northern Australia.[125] Pearl hunting employed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workers, though many were coerced into it.[126] By the 1880s, the introduction of diving suits had reduced Indigenous workers to deckhands.[127] Otherwise Indigenous people congregated at settlements such as Broome (servicing luggers) or Darwin (where 20 percent of the Northern Territory's Indigenous workers were employed).[125] However, in Darwin the Indigenous workers were kept locked up at night.[128] Most of the Indigenous workers in North Queensland, the Northern Territory, and the Kimberley were employed by the cattle industry.[128] Wage payment varied by state. In Queensland, wages were paid from 1901 onwards, being set at a third of white wages in 1911, two-thirds in 1918, and equal in 1930.[129] However, some of the wages were deposited on trust accounts, from which they could be stolen.[129] In the Northern Territory, there was no requirement to pay a wage.[129] Overall, up to the Second World War about half of the Indigenous stockmen received wages, and if so, they were well below the white level.[130] There was also physical abuse of the workers, sometimes including by the police.[131]

On 4 February 1939, Jack Patten led a strike at Cummeragunja Station in New South Wales. The people of Cummeragunja were protesting their harsh treatment under what was a draconian system. A once successful farming enterprise was taken from their control, and residents were forced to subsist on meagre rations. Approximately 200 people left their homes, taking part in the Cummeragunja walk-off, and the majority crossed the border into Victoria, never to return home.[132] Following the rising threat from Empire of Japan, the Australian Army came to the north in the early 1940s, bringing new people and ideas while employing Indigenous workers in defence projects.[133] They were paid a wage and mixed with the regular troops.[133] This led the Northern Territory administration to investigate and recommend paying wages, though it was never enforced.[133] Following meetings held by the white communist Don McLeod in 1942, Indigenous groups in Pilbara decided to go on strike, which they did after the end of the war in the 1946 Pilbara strike.[134] In 1949, they finally won a wage double the size of their original demand, and were encouraged to start their own co-operative based on the mining they had been doing while on strike.[135] Along the war, this event also helped reduce the abuse of Indigenous workers.[136]

Racism and the early civil rights movement[]

As scientific racism developed from Darwinism (with Charles Darwin himself having claimed after visiting New South Wales that the death of "the Aboriginal" was a consequence of natural selection), the popular view of Indigenous Australians started to see them as inferior.[137] Indigenous Australians were considered in the global scientific community as the world's most primitive humans, leading to trade of human remains and relics.[138] This was especially true of Indigenous Tasmanians, with 120 books and articles written by scholars around the world by the late 19th century.[139] Some Indigenous people were also toured and exhibited around the world as spectacles.[140] However, in the 1930s, physical anthropology was taken over by cultural anthropology, which focused cultural difference over inferiority.[141] Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, the father of modern social anthropology, published his Social Organization of Australian Tribes in 1931.[142]

By 1900 most white Australians held racist views of the Indigenous peoples, and the Constitution of Australia of that year did not count them alongside other Australians in the census.[143] Racist treatment was also encoded in special Acts governing Indigenous peoples separately from the rest of society.[144] Racism also manifested itself in everyday discrimination, which was termed the 'colour bar' or the 'caste barrier'.[145] This affected life in most settled parts of Australia, though not that much in the capital cities.[145] For example, from the 1890s to 1949, the New South Wales government removed Indigenous children from state schools if non-Indigenous parents objected to their presence, placing them instead to reserve schools with worse education.[145] The same policy was in place in Western Australia, as well, where only one percent of Indigenous children attended state schools.[145] Indigenous residents of New South Wales were also not permitted to buy or drink alcohol.[145] These kinds of restrictions did not apply in Victoria, with a smaller Indigenous population and an assimilationist policy.[145] Furthermore, Indigenous people were often excluded from organisations, businesses, and sports or recreational facilities, such as pools.[145] Employment and housing was difficult to find for them.[145]

Women's groups, such as the Australian Federation of Women Voters and the National Council of Women of Australia, became advocates for Indigenous issues in the 1920s.[146] The first Indigenous political organisation was the , established in 1924, with 11 branches and over 500 Indigenous members in a year.[147] It had been partly inspired by Marcus Garvey.[147] In 1926, the Native Union in Western Australia was founded.[148] White advocate groups emerged in the 1930s.[146] Other Indigenous organisations included the set up in 1934, the Australian Aborigines' League in 1934, and the Aborigines Progressive Association in 1937.[148] The latter marked Invasion Day on the 150th anniversary of the First Fleet's landing.[148]

Reserves and protection boards[]

The only known treaty between Indigenous and European Australians was Batman's Treaty, signed by Billibellary. His son, Simon Wonga, and other Kulin nation leaders requested land in 1859 for cultivation, and were granted 1820 hectares in the Acheron River by the Victorian government.[149] In 1860, the same government established Aboriginal reserves in Coranderrk, Framlingham, Lake Condah, Ebenezer, Ramahyuck, as well as Lake Tyers.[150] Corranderrk was notably successful, becoming practically self-sufficient and winning the first prize for their hops at the Melbourne International Exhibition.[151] Nevertheless, the inhabitants were refused to be given individual land titles or be paid wages.[152] In South Australia, Raukkan and Poonindie were also set up as communities for Indigenous peoples.[153] In New South Wales, such communities included Maloga, Brungle, Warangesda, and Cummeragunja.[154]

However, the reserve system also gave authorities power over Indigenous people, with the Aboriginal Protection Board exercising control over work and wages, adult movement, and child removal in Victoria from 1869 onwards.[155] With the Half-Caste Act of 1886, the Victorian government started removing those with partial European ancestry from the reserves, with the claimed aim to "merge the half-caste population into the general community", which was also followed in New South Wales with the Aborigines Protection Act 1909.[156] This had deleterious consequences for the viability of the communities, leading to their decline.[156] The Queensland Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act of 1897 became a model for Indigenous legislation in Western Australia (1905), South Australia (1911), and the Northern Territory (1911), which gave the authorities power over anyone deemed 'Aboriginal' in regards to placing them or their children in reserves, denying voting rights or the ability to buy alcohol, as well as prohibiting interracial sexual relations (requiring a ministerial permission for interracial marriage).[157]

The reserves were subsequently mostly reduced, closed and sold off by the 1920s.[158] Meanwhile, the Protection Boards became more powerful in 1915 in New South Wales after new legislation gave them the power to remove children of mixed ancestry without parental or court approval.[159] Later research shows that the authorities aimed to reunite white families without doing so foe Indigenous ones.[159] Overall Indigenous communities in south-eastern Australia became increasingly under government control, with a dependence on weekly rations instead of agricultural work.[160] The 1897 Queensland Act and its subsequent amendments gave reserve superintendents the right to search people and their dwellings or belongings, to confiscate their property and read their mail, as well as to expel them to other reserves, among other powers.[144] The inhabitants had to work 32 hours a week without pay, and were subject to verbal abuse, while their traditions were prohibited.[144]

1940s–present: political activism and equality[]

World War II led to improvements and new opportunities in Indigenous lives through employment in the services and war time industries.[161] After the war, full employment continued, with 96 percent of New South Wales' Indigenous population being employed in 1948.[161] The Commonwealth Child Endowment, as well as the Invalid and Old Age Pensions, were expanded to Indigenous people outside of reserves during the war, though full inclusiveness only followed by 1966.[161] The 1940s also saw individuals given the ability to apply for freedom from Aboriginal Acts, though onerous conditions kept the numbers relatively low.[162] The Nationality and Citizenship Act of 1948 also gave citizenship to any Indigenous people born in Australia.[162] In 1949, the right to vote in federal elections was extended to Indigenous Australians who had served in the armed forces, or were enrolled to vote in state elections.

The postwar era also saw the increased removal of children under assimilationist policies, with between 10 and 33 percent of Aboriginal children being removed from their families between 1910 and 1970.[163] The number may have been over 70,000 across 70 years.[163] By 1961, the Aboriginal population had risen to 106,000.[164] This went hand-in-hand with urbanization, with the population in capital cities increasing by the 1960s with 12,000 in Sydney, 5000 in Brisbane and 2000 in Melbourne.[164]

In 1962, the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders started advocating for wage equality, successfully pressuring the Australian Council of Trade Unions to join the cause.[165] As a result, in 1965 the Australian Industrial Relations Commission declared that there should be no discrimination in Australian industrial relations law.[166] However, after this pastoralists began to mechanize their operations with fencing and helicopters, as well as stating to employ white Australians.[167] By 1971, Indigenous labour had reduced by 30 percent in some places.[167] Unemployment rose massively during the rest of the decade, with Indigenous people being pushed off pastoral properties and gathering in northern towns such as Katherine, Tennant Creek, Halls Creek, Fitzroy Crossing, Broome and Derby.[168]

Indigenous people generally had very poor economic opportunities, with 81 percent of workers being unskilled, 18 percent semi-skilled, and just 1 percent skilled in New South Wales in the mid-'60s.[169] Health differences to the general population were massive, with many times worse infant mortality rates and child health, especially in the Northern Territory.[170] Issues of malnutrition, poverty and poor sanitation led to health effects on children potentially affecting school success.[171] The lack of skills in New South Wales was accompanied with only 4 percent having finished secondary or apprentice training.[172] Heavy drinking was also widespread.[173]

Notable Indigenous individuals during the post-war era included activist Douglas Nicholls, artist Albert Namatjira, opera singer Harold Blair, and actor Robert Tudawali.[174] Many Indigenous people were also successful in sports, with 30 national and 5 commonwealth boxing champions by 1980.[175] Lionel Rose had become the world bantamweight champion in 1968.[175] In tennis, Evonne Goolagong Cawley won 11 Grand Slams in the 1970s.[175] Notable players in rugby and Australian rules football included Polly Farmer, Arthur Beetson, Mark Ella, Glen Ella, Gary Ella.[176]

In 1984, a group of Pintupi people who were living a traditional hunter-gatherer desert-dwelling life were tracked down in the Gibson Desert in Western Australia and brought into a settlement. They are believed to have been the last uncontacted tribe in Australia.[177]

Activism[]

In the 1950s, new political activism for Indigenous rights emerged with 'advancement leagues', which were biracial coalitions.[178] These included the Aboriginal-Australian Fellowship in Sydney and the Victorian Aborigines Advancement League.[178] Similar leagues existed in Perth and Brisbane.[179] A national federation for them was established in 1958 in the form of the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.[179] Conflict over white and Indigenous power within the organisations led to their decline by the 1970s.[180]

Following the Sharpeville massacre, racial issues became a bigger part of student politics, with an educational assistance program called ABSCHOL established by the National Union of Students.[178] In 1965, Charles Perkins organised the Freedom Ride with University of Sydney students, inspired by the American Freedom Riders.[181] The reaction by locals was often violent.[181]

Equality before the law[]

All Indigenous Australians were given the right to vote in Commonwealth elections in Australia by the Menzies government in 1962.[182] The first federal election in which all Aboriginal Australians could vote was held in November 1963. The right to vote in state elections was granted in Western Australia in 1962 and Queensland was the last state to do so in 1965.

The 1967 referendum, passed with a 90% majority, allowed Indigenous Australians to be included in the Commonwealth parliament's power to make special laws for specific races, and to be included in counts to determine electoral representation. This has been the largest affirmative vote in the history of Australia's referenda.

Land rights and self-determination[]

In 1971, Yolngu people at Yirrkala sought an injunction against Nabalco to cease mining on their traditional land. In the resulting historic and controversial Gove land rights case, Justice Blackburn ruled that Australia had been terra nullius before European settlement, and that no concept of Native title existed in Australian law. Although the Yolngu people were defeated in this action, the effect was to highlight the absurdity of the law, which led first to the Woodward Commission, and then to the Aboriginal Land Rights Act.

In 1972, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established on the steps of Parliament House in Canberra, in response to the sentiment among Indigenous Australians that they were "strangers in their own country". A Tent Embassy still exists on the same site.

In 1975, the Whitlam government drafted the Aboriginal Land Rights Act, which aimed to restore traditional lands to Indigenous people. After the dismissal of the Whitlam government by the Governor-General, a reduced-scope version of the Act (known as the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976) was introduced by the coalition government led by Malcolm Fraser. While its application was limited to the Northern Territory, it did grant "inalienable" freehold title to some traditional lands.

A 1987 federal government report described the history of the "Aboriginal Homelands Movement" or "Return to Country movement" as "a concerted attempt by Aboriginal people in the 'remote' areas of Australia to leave government settlements, reserves, missions and non-Aboriginal townships and to re-occupy their traditional country".[183]

In 1992, the Australian High Court handed down its decision in the Mabo Case, declaring the previous legal concept of terra nullius to be invalid. This decision legally recognised certain land claims of Indigenous Australians in Australia prior to British Settlement. Legislation was subsequently enacted and later amended to recognise Native Title claims over land in Australia.

Later debates over history and contemporary status[]

In 1998, as the result of an inquiry into the forced removal of Indigenous children (see Stolen generation) from their families, a National Sorry Day was instituted, to acknowledge the wrong that had been done to Indigenous families. Many politicians, from both sides of the house, participated, with the notable exception of the Prime Minister, John Howard.

In 1999 a referendum was held to change the Australian Constitution to include a preamble that, amongst other topics, recognised the occupation of Australia by Indigenous Australians prior to British Settlement. This referendum was defeated, though the recognition of Indigenous Australians in the preamble was not a major issue in the referendum discussion, and the preamble question attracted minor attention compared to the question of becoming a republic.

In 2004, the Australian Government abolished The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), which had been Australia's top Indigenous organisation. The Commonwealth cited corruption and, in particular, made allegations concerning the misuse of public funds by ATSIC's chairman, Geoff Clark, as the principal reason. Indigenous specific programmes have been mainstreamed, that is, reintegrated and transferred to departments and agencies serving the general population. The Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination was established within the then Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs, and now with the Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs to co-ordinate a "whole of government" effort. Funding was withdrawn from remote homelands (outstations).[184]

In 2008, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd made a formal apology for the Stolen Generations.

See also[]

- Aboriginal Australian identity

- Aboriginal History (journal)

- Aboriginal history of Western Australia

- Aboriginal reserve

- Aboriginal land rights in Australia

- Aboriginal South Australians

- Aboriginal Tasmanians

- Aboriginal Victorians

- Australian archaeology

- Bringing them home report (1997)

- Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? (2014 book)

- Farmers or Hunter-Gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate (2021 book)

- History of Indigenous Australian self-determination

- History wars

- List of Aboriginal missions in New South Wales

- List of Indigenous Australian firsts

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

- Native title in Australia

- Stolen Generations

References[]

- ^ Clarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; Marwick, Ben; et al. (2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago" (PDF). Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C. doi:10.1038/nature22968. hdl:2440/107043. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28726833. S2CID 205257212.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel. London: Random House. pp. 314–316.

- ^ "Colonisation: Initial invasion and colonisation (1788 to 1890)". Working with Indigenous Australians. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ Evans, R. (2007). A History of Queensland. Cambridge UK: Cambridge U. Press. pp. 10–12. ISBN 978-0-521-54539-6.

- ^ Gordon Briscoe; Len Smith, eds. (2002), "2. How many people had lived in Australia before it was annexed by the English in 1788?", The Aboriginal Population Revisited: 70,000 years to the present, Canberra, Aboriginal Studies Press

- ^ D. Hopkins, Princes and Peasants, Chicago, 1983, p. 207; Judy Campbell, Invisible Invaders: Smallpox and Other Diseases in Aboriginal Australia 1780–1880, Melbourne, 2002, pp. 10, 39–50

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smallpox Through History. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009.

- ^ Pascoe, Bruce (2007). Convincing Ground: Learning to Fall in Love with Your Country. Aboriginal Studies Press. ISBN 978-0-85575-549-2.

- ^ Calla Wahlquist (2018). "Evidence of 250 massacres of Indigenous Australians mapped". Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Crabtree, Stefani; Williams, Alan N; Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; White, Devin; Saltré, Frédérik; Ulm, Sean (30 April 2021). "We mapped the 'super-highways' the First Australians used to cross the ancient land". The Conversation. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Russell, Lynette; Bird, Michael; Roberts, Richard 'Bert'. "Fifty years ago, at Lake Mungo, the true scale of Aboriginal Australians' epic story was revealed". The Conversation. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ Lourandos, Harry. Continent of Hunter-Gatherers: New Perspectives in Australian Prehistory (Cambridge University Press, 1997) p.81

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Morse, Dana (30 April 2021). "Researchers demystify the secrets of ancient Aboriginal migration across Australia". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Williams, Alan N.; Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; Saltré, Frédérik; Norman, Kasih; Ulm, Sean. "The First Australians grew to a population of millions, much more than previous estimates". The Conversation. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ Crabtree, Stefani A.; White, Devin A.; Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; Saltré, Frédérik; Williams, Alan N.; Beaman, Robin J.; Bird, Michael I.; Ulm, Sean (29 April 2021). "Landscape rules predict optimal superhighways for the first peopling of Sahul". Nature Human Behaviour: 1–11. doi:10.1038/s41562-021-01106-8. ISSN 2397-3374. PMID 33927367. S2CID 233458467.

- ^ Clarkson, Chris; Smith, Mike; Marwick, Ben; Fullagar, Richard; Wallis, Lynley A.; Faulkner, Patrick; Manne, Tiina; Hayes, Elspeth; Roberts, Richard G.; Jacobs, Zenobia; Carah, Xavier; Lowe, Kelsey M.; Matthews, Jacqueline; Florin, S. Anna (June 2015). "The archaeology, chronology and stratigraphy of Madjedbebe (Malakunanja II): A site in northern Australia with early occupation". Journal of Human Evolution. 83: 46–64. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.03.014. PMID 25957653. "The stone artefacts and stratigraphic details support previous claims for human occupation 50–60 ka and show that human occupation during this time differed from later periods"

- ^ Roberts, Richard G.; Jones, Rhys; Smith, M. A. (May 1990). "Thermoluminescence dating of a 50,000-year-old human occupation site in northern Australia". Nature. 345 (6271): 153–156. Bibcode:1990Natur.345..153R. doi:10.1038/345153a0. ISSN 0028-0836. S2CID 4282148.

- ^ Monroe, M. H. (28 April 2016). "Malakunanja II Arnhem land". Australia: The Land Where Time Began. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ Attenbrow, Val (2010). Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records. Sydney: UNSW Press. pp. 152–153. ISBN 978-1-74223-116-7. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Stockton, Eugene D.; Nanson, Gerald C. (April 2004). "Cranebrook Terrace Revisited". Archaeology in Oceania. 39 (1): 59–60. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.2004.tb00560.x. JSTOR 40387277.

- ^ Dortch, C.E.; Hesp, Patrick A. (1994). "Rottnest Island artifacts and palaeosols in the context of Greater Swan Region prehistory". Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia. Perth: Royal Society of Western Australia. 77: 23–32. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- ^ Flannery, Tim "The Future Eaters"

- ^ Oppenheimer, Stephen, (2004),"Out of Eden: The Peopling of the World"(Constable and Robinson; New Ed)

- ^ http://[www.bradshawfoundation.com/journey/]

- ^ Oppenheimer, Stephen "The Real Eve: Modern Man's Journey Out of Africa"(Carroll & Graf Publishers)(ISBN 0-7867-1334-8)

- ^ Mulvaney, J. and Kamminga, J., (1999), Prehistory of Australia. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington.

- ^ Tindale's Catalogue of Australian Aboriginal Tribes: Tjapukai (QLD) Archived 26 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Keith Windschuttle and Tim Gillin (June 2002). "The extinction of the Australian pygmies". Quadrant, Sydney Line. Archived from the original on 8 December 2002. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ "Colin Groves: 'Australia for the Australians'". Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bergström, Anders; Nagle, Nano; Chen, Yuan; McCarthy, Shane; Pollard, Martin O.; Ayub, Qasim; Wilcox, Stephen; Wilcox, Leah; Oorschot, Roland A.H. van; McAllister, Peter; Williams, Lesley; Xue, Yali; Mitchell, R. John; Tyler-Smith, Chris (21 March 2016). "Deep Roots for Aboriginal Australian Y Chromosomes". Current Biology. 26 (6): 809–813. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.028. PMC 4819516. PMID 26923783.

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

- ^ Irina Pugach; Frederick Delfin; Ellen Gunnarsdóttir; Manfred Kayser; Mark Stoneking (14 January 2013). "Genome-wide data substantiate Holocene gene flow from India to Australia". PNAS. 110 (5): 1803–1808. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1803P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211927110. PMC 3562786. PMID 23319617.

- ^ Aboriginal genes suggest Indian migration Archived 20 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine Australian Geographic 15 January 2013

- ^ Coukell, Allan (May 2001). "Could mysterious figures lurking in Australian rock art be the world's oldest shamans?". New Scientist. p. 34.

- ^ J.G. Luly et.al Last Glacial Maximum habitat change and its effects on the grey-headed flying fox James Cook University, Townsville, Queensland

- ^ Jump up to: a b McGowan, Hamish; Marx, Samuel; Moss, Patrick; Hammond, Andrew (28 November 2012). "Evidence of ENSO mega-drought triggered collapse of prehistory Aboriginal society in northwest Australia: ENSO MEGA-DROUGHT". Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (22). doi:10.1029/2012GL053916.

- ^ Dodson, J.R. (September 2001). "Holocene vegetation change in the mediterranean-type climate regions of Australia". The Holocene. 11 (6): 673–680. Bibcode:2001Holoc..11..673D. doi:10.1191/09596830195690. S2CID 128689357.

- ^ Jonathan Adams Australasia during The Last 150,000 Years Archived 26 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine Environmental Sciences Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- ^ M.H.Monroe Last Glacial Maximum in Australia Australia: The Land Where Time Began: A biography of the Australian continent

- ^ Jump up to: a b Flood, Josephine (1994), "Archaeology of the Dreamtime" (Angus & Robertson; 2Rev Ed)(ISBN 0-207-18448-8)

- ^ McOwan, Johannah (26 November 2014). "Indigenous stories accurately tell of sea level rises, land mass reductions over 10,000 years, research suggests". ABC Online. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ Reid, Nick; Nunn, Patrick D. (12 January 2015). "Ancient Aboriginal stories preserve history of a rise in sea level". The Conversation. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Corbett, Laurie (1995), "The Dingo: in Australia and Asia"

- ^ Flannery, Tim "The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australian Lands and People" (Grove Press)(ISBN 0-8021-3943-4)

- ^ Westaway, Michael; Olley, Jon; Grun, Rainer (12 January 2017). "Aboriginal Australians co-existed with the megafauna for at least 17,000 years". The Conversation. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ Gammage, Bill (October 2011). The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Allen & Unwin. pp. 281–304. ISBN 978-1-74237-748-3.

- ^ Davies, S. J. J. F. (2002). Ratites and Tinamous. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854996-2

- ^ "Indigenous Australians 'farmed bananas 2,000 years ago'". BBC News. 12 August 2020.

- ^ Gammage, Bill (October 2011). The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Allen & Unwin. pp. 281–304. ISBN 978-1-74237-748-3.

- ^ Beaglehole, J.C. (1955). The Journals of Captain James Cook, Vol.1. Cambridge: Hakluyt Society. p. 387. ISBN 978-0851157443.

- ^ Cameron-Ash, M. (2018). Lying for the Admiralty. Rosenberg. pp. 180–184. ISBN 9780648043966.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Frost, Alan (2012). The First Fleet: the real story. Collingwood: Black Inc. ISBN 9781863955614.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Frost, Alan (1994). Botany Bay Mirages. Melbourne University Press. pp. 190–210. ISBN 9780522844979.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Radford, Ron (2010). "Portrait of Nannultera, a young Poonindie cricketer". Collection highlights: National Gallery of Australia. National Gallery of Australia. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ "The War for the land: A Short History of Aboriginal-European relations in Cairns". Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ "The Statistics of Frontier Conflict". Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Kohen, J. L. (2005). "Pemulwuy (1750–1802)". Pemulwuy (c. 1750 – 1802). Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ^ Connor, John (2002). The Australian frontier wars, 1788–1838. Sydney: UNSW Press. ISBN 978-0-86840-756-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Clements 2014, p. 1

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 143

- ^ Clements 2014, p. 4

- ^ "Invisible Invaders". Archived from the original on 4 September 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Judy Campbell, Invisible Invaders. Melbourne University Press. 1998. ISBN 9780522849394.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Smallpox epidemic". National Museum Australia. Defining moments. Retrieved 1 March 2019. (Includes further citations)

- ^ Mear, Craig (June 2008). "The origin of the smallpox outbreak in Sydney in 1789". Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society. Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Warren, Christopher (March 2014). "Smallpox at Sydney Cover - who, when and why?" (PDF). Journal of Australian Studies. 38 (1). doi:10.1080/14443058.2013.849750. S2CID 143644513. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Van Dyk, Robyn (24 April 2008). "Aboriginal ANZACS". Australian War Memorial.

- ^ "Lest We Forget". Message Stick. Season 9. Episode 10. 23 April 2007.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 207. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ http://www.koorihistory.com/jack-patten/ Koori History: Remembering Jack Patten

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. pp. 104–106. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.

- ^ Broome, Richard (5 November 2019). Aboriginal Australians: A history since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-76087-262-5.