Hiawatha Service

A Hiawatha Service train at Glenview in 2018 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service type | Inter-city rail | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Active | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Illinois/Wisconsin, United States | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Milwaukee Road corridor trains | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First service | May 1, 1971 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current operator(s) | Amtrak, in partnership with Illinois and Wisconsin Departments of Transportation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ridership | 2,297 daily 838,355 (total) (FY12)[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Route | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Start | Milwaukee, Wisconsin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stops | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| End | Chicago, Illinois | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance travelled | 86 mi (138 km) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Average journey time | 1 hour, 29 minutes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service frequency | Seven daily each way (Mon–Sat) Six daily each way (Sun) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Train number(s) | 329–344 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| On-board services | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class(es) | Coach | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Seating arrangements | Airline-style Coach seating (unreserved) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Catering facilities | None | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baggage facilities | Checked baggage available at Chicago and Milwaukee | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rolling stock | Horizon Fleet and Amfleet coaches | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | 79 mph maximum, 57 mph (92 km/h) average, including stops | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

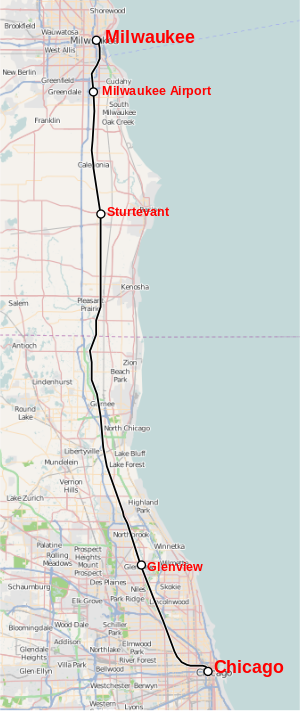

The Hiawatha Service, or simply Hiawatha, is an 86-mile (138 km) train route operated by Amtrak on the western shore of Lake Michigan between Chicago, Illinois and Milwaukee, Wisconsin. However, the name was historically applied to several different routes that extended across the Midwest and to the Pacific Ocean. As of 2007, fourteen trains (seven round-trips, six on Sunday) run daily between Chicago and Milwaukee,[2] making intermediate stops in Glenview, Illinois, Sturtevant, Wisconsin, and Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport. The line is partially supported by funds from the state governments of Wisconsin and Illinois.[3]

The service carried over 800,000 passengers in fiscal year 2011, a 4.7% increase over FY2010. Revenue during FY2011 totaled $14,953,873, a 6.1% increase over FY2010.[1] It is Amtrak's ninth-busiest route, and the railroad's busiest line in the Midwest.[1] Ridership has been steadily increasing, with 8 of the last 9 years showing ridership increases as of 2013.[4] Ridership per mile is also very high, exceeded only by the Northeast Regional and the Capitol Corridor. A one-way trip between Milwaukee and Chicago takes about 90 minutes. In the 1930s, the same trip took 75 minutes on the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad's Hiawatha.[5] In 2014, free Wi-Fi service was added to the Hiawatha Service.[6]

The route is augmented by Amtrak Thruway Motorcoach routes connecting Green Bay, Appleton, Oshkosh, and Fond du Lac with Milwaukee and Madison, Janesville, and Rockford with Chicago.

The Hiawatha Service is the shortest route on the Amtrak system since the 2019 extension of the New Haven–Springfield Shuttle.[7]

On April 24, 2020, the Hiawtha was temporarily replaced by bus service due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Partial service resumed in June 2020, and full service in May 2021.

History[]

Milwaukee Road[]

Historically, the Hiawathas were operated by the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (also known as the "Milwaukee Road"), and initially traveled from Chicago to the Twin Cities. The first Hiawatha trains ran in 1935. By 1948, there were five routes carrying the Hiawatha name: Chicago–Minneapolis, Chicago–Omaha, Chicago–Wausau–Minocqua, Chicago–Ontanogan, and Chicago-Minneapolis-Seattle.

The Hiawathas were among the world's fastest trains in the 1930s and 1940s, and these trains reached some of their peak speeds on this stretch, directly competing with trains from the Chicago and North Western Railway which ran on roughly parallel tracks. A 90-minute non-stop service between Chicago and Milwaukee was first introduced in the mid-1930s, and this later fell to 75 minutes for several years. A self-imposed 100 miles per hour (161 km/h) speed limit was routinely exceeded by locomotive engineers, until the Interstate Commerce Commission rules imposed a stricter limit of 90 mph (145 km/h) in the early 1950s. The train slowed to a schedule of 80 minutes, though an added stop in Glenview also contributed to a longer travel time. Ultimately, the speed limit fell to 79 mph (127 km/h) in 1968 because of signaling changes, and the scheduled duration went back to 90 minutes end-to-end.[8]

Amtrak[]

Under Amtrak, which assumed control of most intercity passenger rail service in the United States on May 1, 1971, the Hiawatha name survived in two forms. The first was a Chicago–Milwaukee–Minneapolis service, known simply as the Hiawatha. This would be renamed the Twin Cities Hiawatha, then extended to Seattle and renamed the North Coast Hiawatha. This service ended in 1979.[9]:30–31; 73

The second was a Chicago–Milwaukee corridor train known as the Hiawatha Service (as opposed to Hiawatha). Although Amtrak had retained Chicago–Milwaukee service during the transition, it did not name these trains until October 29, 1972. At this time both Hiawatha and Hiawatha Service could be found on the same timetable. On June 15, 1976, Amtrak introduced Turboliners to the route and the name Hiawatha Service left the timetable, not to return until 1989. The Chicago–Milwaukee trains were known simply as "Turboliners" (as were comparable trains on the Chicago–Detroit and Chicago – St. Louis corridors) until October 26, 1980, when Amtrak introduced individual names for each of the trains: The Badger, the LaSalle, the Nicollet, and the Radisson. This practice ended on October 29, 1989, when the name Hiawatha Service returned as an umbrella term for all Chicago–Milwaukee service.[10]

A resurfacing project on Interstate 94 led to a three-month trial of service west of Milwaukee to Watertown, Wisconsin beginning on April 13, 1998. Intermediate stops included Wauwatosa, Elm Grove, Pewaukee, and Oconomowoc. Amtrak extended four of the six daily Hiawathas over the route. The Canadian Pacific Railway, which owned the tracks through its American subsidiary Soo Line Railroad, estimated that the route would require between $15–33 million in capital investment before it could host the extended service permanently. Money was not forthcoming and service ended July 11. The three-month trial cost $1.4 million and carried 32,000 passengers.[11]:184[12][13]

Between 2000 and 2001, Amtrak considered extending one Hiawatha Service round-trip 70 miles (113 km) north from Milwaukee to Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. Potential stops included Elm Grove, Brookfield, Slinger, and Lomira. Travel time would be nearly two hours. Amtrak hoped to attract mail and express business along the route as part of its Network Growth Strategy, similar to the short-lived Lake Country Limited. Amtrak abandoned the idea in September 2001.[14]

In 2005, another station opened on the line, the Milwaukee Airport Railroad Station at Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport. The expansion was intended to facilitate travel to and from the airport, with shuttles running between the station and the main terminal. The new station also gave residents on the south side of Milwaukee easier access to the service, along with an alternative to the central station in downtown, which is now fully accessible after completion of the Marquette Interchange. The station was primarily funded and is maintained by the Wisconsin Department of Transportation.[citation needed]

It is proposed that the Hiawatha Service, along with the Empire Builder, would shift one stop north to North Glenview in Glenview, Illinois. This move would eliminate lengthy stops which block traffic on Glenview Road. This move would involve reconstruction of the North Glenview station to handle the additional traffic, and depends on commitments from Glenview, the Illinois General Assembly, and Metra.[15]

The route is coextensive with the far southern leg of the Empire Builder, Amtrak's long-distance service from Chicago to the Pacific Northwest. The Empire Builder stops at Glenview and Milwaukee, but normally does so in both cases only to receive passengers northbound and discharge passengers southbound.

COVID-19 pandemic[]

Train service was suspended on April 24, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, replaced with an Amtrak Thruway Motorcoach route between Milwaukee and Chicago.[16] To make up for the loss of service, the Empire Builder added stops at Sturtevant and Milwaukee Airport, and temporarily allowed local travel between Chicago and Milwaukee.

The Hiawatha returned on June 1, 2020, with a single round trip: a morning departure to Chicago and an evening return to Milwaukee. Three daily round trips and two weekend round trips returned on June 29. The Hiawatha had long run with a mix of reserved and unreserved seating, but Amtrak, IDOT, and WisDOT temporarily required reservations for passengers without multi-ride tickets in order to maintain social distancing. Amtrak also required facial coverings and stopped accepting cash. The Peak Fare Surcharge was suspended for these trains.[17]

On May 23, 2021, Hiawatha Service returned to its full pre-pandemic schedule. Thruway bus service to Green Bay also resumed that day.[18]

Future expansion[]

In 2009, Wisconsin applied for funding from an $8 billion pool allocated for rail projects under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, and the Chicago–Milwaukee–Madison–Minneapolis/St. Paul corridor was allocated $823 million.[19] $810 million of that was to support extending Amtrak services to Madison, which had not seen direct intercity service since 1971. Another $12 million would have been used to upgrade the line between Chicago and Milwaukee, and an additional $600,000 was granted to study future alignments to the Twin Cities.[20][21]

The Madison extension was initially planned to include stops in Brookfield, Oconomowoc, and Watertown,[19] but Oconomowoc and Brookfield were reluctant to move forward with station planning due to cost concerns. The Wisconsin Department of Transportation (WisDOT) dropped Oconomowoc from the planned route in August 2010,[22] and Brookfield was waiting to see the outcome of elections in November before making a decision on whether to build a station.[23] The nearby cities of Hartland and Wauwatosa had expressed interest in hosting stations. The extension was expected to begin service by 2013.

The project became a political issue in the 2010 Wisconsin gubernatorial election. Republican candidate Scott Walker promised he would stop the project and return the money the state received if elected.[24] When asked whether it would be realistic to stop work, Governor Doyle expressed pessimism and said in part:

This is about an interstate high-speed rail system in the United States. Just like the Interstate Highway System–that's a federal system. [...] Short of sitting down in front of the federal government and defying the federal government, I don't think it's realistic to say that this project would stop.[25]

At the end of October 2010, Wisconsin governor Jim Doyle and the federal government signed an agreement that bound the state to spend the federal funds granted to construct the route, regardless of the results of the 2010 gubernatorial election.[26] On November 4, two days after Scott Walker won the gubernatorial election, however, Doyle ordered work on the line to be temporarily halted,[27] and on November 9 said that he planned to leave the choice of whether or not to operate the train to Walker.[28]

On December 9, 2010, U.S. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood announced that much of the $810 million that Wisconsin was supposed to get would be redistributed to other states, including California, Florida, and Washington.

The project was awarded a $31.8 million federal grant in 2020.[29] The line was included in Amtrak's plans that year for expanding intermediate-distance services throughout the country.[30][31]

The cars currently in use will be replaced with Siemens Venture (or CALIDOT) railcars and cab control cars for Siemens Charger locomotives around 2022.

Corridor names[]

This table shows the names given to trains which operated over the Chicago-Milwaukee corridor under Amtrak. It excludes long-distance trains such as the Empire Builder and North Coast Hiawatha whose local stopping patterns were restricted. The Abraham Lincoln and Prairie State were Chicago-St. Louis services which Amtrak extended through Chicago to the north in the early 1970s.

| 1971-11-14 | 1972-10-29 | 1973-10-28 | 1975-11-30 | 1976-06-15 | 1980-10-26 | 1984-10-28 | 1985-04-28 | 1989-10-29 | Present |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham Lincoln | |||||||||

| Prairie State | |||||||||

| Hiawatha Service | Hiawatha Service | ||||||||

| Turboliner | |||||||||

| LaSalle | |||||||||

| Marquette | |||||||||

| Nicollet | |||||||||

| Radisson | |||||||||

| Badger | |||||||||

| Encore | |||||||||

Ridership[]

| Passenger volume | Change over previous year | Ticket Revenue | Change over previous year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007[32] | 595,336 | $10,230,272 | ||

| 2008[32] | 749,659 | $13,138,765 | ||

| 2009[32] | 738,231 | $13,300,511 | ||

| 2010[33] | 783,060 | $14,092,803 | ||

| 2011[33] | 819,493 | $14,953,873 | ||

| 2012[34] | 838,355 | $15,963,261 | ||

| 2013[35][note 1] | 778,469 | $16,287,184 | ||

| 2014[35] | 799,638 | $16,794,044 | ||

| 2015 | 799,271 | |||

| 2016[36] | 807,720 | |||

| 2017[37] | 829,000 | |||

| 2018[38] | 844,396 | |||

| 2019[39] | 882,189 | |||

| 2020[40] | 403,112 | - | - |

Due primarily to the route's popularity, its northern terminus, Milwaukee Intermodal Station, is Amtrak's 18th-busiest station nationwide and second-busiest in the Midwest.[41]

Notes:

- ^ The 2013 and subsequent numbers have been adjusted to account for multi-ride tickets.

Equipment[]

Two trainsets are required to operate the service. The usual Hiawatha train sets are formed of one Siemens SC-44 locomotive on the southward end, an EMD F40PH derived "cabbage car" on the northward end, and six Horizon Fleet 68-seat coaches. One car at the rear end in the direction of travel is designated a "quiet" car with limitations placed on cell phone usage and loud conservations. During winter months, an Amfleet coach is normally used on each end in lieu of a Horizon coach to serve as quiet cars.

On July 17, 2009, the State of Wisconsin announced it would purchase two new train sets from Spanish manufacturer Talgo in preparation for the enhanced-speed service that received funding in early 2010. However, Governor Scott Walker rejected the federal funding and cancelled the project. Talgo opened a manufacturing plant in Milwaukee to construct the trainsets for the Hiawatha Service, and the company hoped the plant would also build trains for future high-speed lines in the region.[42] The two sets built were stored in the former Talgo plant until May 2014, when Amtrak moved them to its maintenance facility near Indianapolis, Indiana. They will remain stored there pending their possible use on other Amtrak routes. The unpowered tilting trainsets are 14 cars long including a cab car, eleven coaches (five of which have restrooms), one bistro car, and one end car including a bicycle rack. The cars wear a red-and-white livery in homage to the University of Wisconsin. The trains would have initially been pulled by the same GE Genesis locomotives used at the time, which have a top speed of 110 mph.[43] The two trainsets have since been acquired by the Washington State DOT for the Cascades service, and as of 2021 were undergoing refurbishment at the Talgo facility in Milwaukee.[44]

In August 2019, the Federal Railroad Administration awarded WisDOT up to $25.2 million to purchase six new coaches and three new cab cars for the route, allowing the replacement of the NPCUs.[45]

Station stops[]

| State | Town/City | Station | Connections |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illinois | Chicago | Chicago Union Station | |

| Glenview | Glenview station | ||

| Wisconsin | Sturtevant | Sturtevant Amtrak Station | |

| Milwaukee | Milwaukee Airport Railroad Station | Airport shuttle to Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport | |

| Milwaukee Intermodal Station |

See also[]

References[]

Route map:

| ( • help)

|

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Amtrak Ridership Rolls Up Best-Ever Records" (PDF). Amtrak. October 10, 2012.

- ^ Wisconsin Department of Transportation (May 1, 2007). "Rail Transportation in Wisconsin". Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ^ "Amtrak Hiawatha Service breaks ridership record" (Press release). Wisconsin Department of Transportation. January 11, 2007. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- ^ Mulvany, Lydia (August 15, 2013). "Amtrak's Hiawatha route tops monthly ridership record". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ^ "Official Guide". September 1938.

- ^ Docter, Cary (February 10, 2014). "Free Wi-Fi now available on Amtrak's Hiawatha Service". Fox6 News Milwaukee.

- ^ "Amtrak System Timetable" (PDF). Amtrak. January 2018. Retrieved February 21, 2018.

- ^ Scribbins, Jim (2007) [1970]. The Hiawatha Story. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-5003-9. OCLC 191732983.

- ^ Goldberg, Bruce (1981). Amtrak--the first decade. Silver Spring, MD: Alan Books. OCLC 7925036.

- ^ James Sponholz. "Timeline of Hiawatha Corridor Timetables". Archived from the original on September 18, 2011. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- ^ Sanders, Craig (2006). Amtrak in the Heartland. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34705-3.

- ^ "Amtrak temporary service extension approved". Telegraph-Herald. February 28, 1998. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ Sandler, Larry (July 14, 1998). "Madison-Chicago rail link discussed". Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "AMTRAK DROPS FOND DU LAC PLAN". Capital Times – via HighBeam Research (subscription required). September 11, 2001. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ^ "Amtrak eyes moving Ill. station". Railway Track and Structures. November 11, 2009. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- ^ Varon, Roz (April 24, 2020). "Busses replace trains on Amtrak Hiawatha line between Chicago and Milwaukee during coronavirus pandemic". ABC7 Chicago. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ "Amtrak to restore Amtrak Hiawatha Service from Milwaukee to Chicago on June 1". The Milwaukee Independent. May 30, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ Teixeira, Gunner (May 25, 2021). "Amtrak Hiawatha returns to full-service bus routes". WFRV Local 5 - Green Bay, Appleton. Retrieved August 9, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fact Sheet: High Speed Intercity Passenger Rail Program: Minneapolis/St. Paul - Madison - Milwaukee - Chicago". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on January 21, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2010 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Wis to get $822 million for rail". Chicago Tribune. Associated Press. January 28, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ "Minnesota receives federal stimulus funds to study high-speed rail". Minnesota Department of Transportation. January 29, 2009. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ Sean Ryan (August 19, 2010). "WisDOT nixes Oconomowoc high-speed rail stop". The Business Journal of Milwaukee. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ^ "Brookfield station decision delayed until after election". The Business Journal of Milwaukee. September 24, 2010. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ^ "Walker would give back $810M for high-speed rail". Associated Press/WLUK-TV. August 16, 2010. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ^ "Madison high speed rail station Q+A". Learfield News. YouTube. July 1, 2010. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ^ "Wisconsin high-speed rail project "locked in"". Trains Magazine. November 2, 2010. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ "State halts work on high speed rail line". Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel. November 4, 2010. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ "Anti-rail Wisconsin Governor-elect will decide on fast-train plan". Trains Magazine. November 9, 2010. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ Weniger, Deanna (September 22, 2020). "Ramsey County commissioner announces $31.8 million federal grant for second Amtrak train". Twin Cities Pioneer Press. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ McMurtry, Ian (October 24, 2020). "Amtrak 2035: Does Amtrak Finally Have a Strong Plan Against Airlines?". Airline Geeks. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ Anderson, Eric (February 5, 2021). "Amtrak route restructure targets new corridors". Times Union. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Amtrak Fiscal Year 2009, October 2008–September 2009 (compared with Fiscal Years 2008 and 2007)" (PDF).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Amtrak (October 13, 2011). "Amtrak Ridership Rolls Up Best-Ever Records" (PDF) (Press release).

- ^ "Amtrak Fiscal Year 2013 Ridership and Revenue (10/01/12-9/30/13)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 24, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Amtrak (October 27, 2014). "Amtrak Ridership and Revenues Continue Strong Growth in FY 2014" (PDF) (Press release). Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- ^ name="Amtrak">"Amtrak Delivers Strong FY 2016 Financial Results". Retrieved November 21, 2016.

- ^ "Amtrak Route Ridership" (PDF). Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- ^ "Passenger traffic on Amtrak's Milwaukee to Chicago line hits new high".

- ^ "Amtrak FY19 Ridership" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ Luczak, Marybeth (November 23, 2020). "Amtrak Releases FY 2020 Data". Railway Age. New York: Simmons-Boardman Publishing Inc. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Amtrak national fact sheet FY2018

- ^ "Doyle enters Midwest pact to pursue high-speed rail funds". The Business Journal of Milwaukee. July 27, 2009. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ Kay Nolan (September 9, 2010). "Talgo trains to sport Badger colors, traditional locomotives". WisBusiness.com. Retrieved September 26, 2010.

- ^ Federal Railroad Administration (February 1, 2018). "Petition for Waiver of Compliance" (PDF). Federal Register. Government Publishing Office. 83 (22): 4728.

- ^ "U.S. Transportation Secretary Elaine L. Chao Announces $272 Million in 'State of Good Repair' Program Grants" (Press release). Federal Railroad Administration. August 21, 2019.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hiawatha Service. |

- Amtrak routes

- Passenger rail transportation in Wisconsin

- Passenger rail transportation in Illinois