Historical materialism

This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations for an encyclopedic entry. (December 2018) |

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

|

Historical materialism, also known as the materialist conception of history, is a methodology used by scientific socialists and Marxist historiographers to understand human societies and their development through history, arguing that history is the result of material conditions rather than ideals. This was first articulated by Karl Marx (1818–1883) as the "materialist conception of history".[1] It is principally a theory of history which asserts that the material conditions of a society's mode of production, or in Marxist terms the union of a society's productive forces and relations of production, fundamentally determine society's organization and development. Historical materialism is a fundamental aspect of Marx and Engels' scientific socialism, arguing that applying a scientific analysis to the history of human society reveals fundamental contradictions within the capitalist system that will be resolved when the proletariat seizes state power and begins the process of implementing socialism.[2]

Historical materialism is materialist as it does not believe that history has been driven by individuals' consciousness or ideals, but rather subscribes to the philosophical monism that matter is the fundamental substance of nature and therefore the driving force in all of world history.[3] In contrast, idealists believe that human consciousness creates reality rather than the materialist conception that material reality creates human consciousness. This put Marx in direct conflict with groups like the liberals who believed that reality was governed by some set of ideals,[2] when he stated in The German Ideology: "Communism is for us not a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things. The conditions of this movement result from the premises now in existence".[2]

In seeking the causes of developments and changes in human society, historical materialism focuses on the means by which humans collectively produce the necessities of life. It posits that social classes and the relationship between them, along with the political structures and ways of thinking in society, are founded on and reflect contemporary economic activity.[4] Since Marx's time, the theory has been modified and expanded by some writers. It now has many Marxist and non-Marxist variants. Many Marxists contend that historical materialism is a scientific approach to the study of history.[5]

History and development[]

Origins[]

Attempts at analyzing history in a scientific, materialist manner originated in France during the Age of Enlightenment with thinkers such as the philosophes Montesquieu and Condorcet and the physiocrat Turgot.[6] Inspired by these earlier thinkers, especially Condorcet, the Utopian socialist Henri de Saint-Simon formulated his own materialist interpretation of history, similar to those later used in Marxism, analyzing historical epochs based on their level of technology and organization and dividing them between eras of slavery, serfdom, and finally wage labor.[7] According to the socialist leader Jean Jaurès, the French writer Antoine Barnave had priority in first developing the theory that economic forces are the driving factors in history.[8] Karl Marx never used the words "historical materialism" to describe his theory of history; the term first appears in Friedrich Engels' 1880 work Socialism: Utopian and Scientific,[9] to which Marx wrote an introduction for the French edition.[10] By 1892, Engels indicated that he accepted the broader usage of the term "historical materialism," writing the following in an introduction to an English edition of Socialism: Utopian and Scientific;

This book defends what we call "historical materialism", and the word materialism grates upon the ears of the immense majority of British readers. [...] I hope even British respectability will not be overshocked if I use, in English as well as in so many other languages, the term "historical materialism", to designate that view of the course of history which seeks the ultimate cause and the great moving power of all important historic events in the economic development of society, in the changes in the modes of production and exchange, in the consequent division of society into distinct classes, and in the struggles of these classes against one another.[11]

Marx's initial interest in materialism is evident in his doctoral thesis which compared the philosophical atomism of Democritus with the materialist philosophy of Epicurus[12][13] as well as his close reading of Adam Smith and other writers in classical political economy.

Marx and Engels first state and detail their materialist conception of history within the pages of The German Ideology, written in 1845. The book, which structural Marxists such as Louis Althusser[14] regard as Marx's first 'mature' work, is a lengthy polemic against Marx and Engels' fellow Young Hegelians and contemporaries Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer, and Max Stirner. Stirner's 1844 work The Unique and its Property had a particularly strong impact[15] on the worldview of Marx and Engels: Stirner's blistering critique of morality and whole-hearted embrace of egoism prompted the pair to formulate a conception of socialism along lines of self-interest rather than simple humanism alone, grounding that conception in the scientific study of history.[16]

Perhaps Marx's clearest formulation of historical materialism resides in the preface to his 1859 book A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy:

The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.[17]

Continued development[]

In a foreword to his essay Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (1886), three years after Marx's death, Engels claimed confidently that "the Marxist world outlook has found representatives far beyond the boundaries of Germany and Europe and in all the literary languages of the world."[18] Indeed, in the years after Marx and Engels' deaths, "historical materialism" was identified as a distinct philosophical doctrine and was subsequently elaborated upon and systematized by Orthodox Marxist and Marxist–Leninist thinkers such as Eduard Bernstein, Karl Kautsky, Georgi Plekhanov and Nikolai Bukharin. This occurred despite the fact that many of Marx's earlier works on historical materialism, including The German Ideology, remained unpublished until the 1930s.

In the early years of the 20th century, historical materialism was often treated by socialist writers as interchangeable with dialectical materialism, a formulation never used by Marx or Engels.[19] According to many Marxists influenced by Soviet Marxism, historical materialism is a specifically sociological method, while dialectical materialism refers to the more general, abstract philosophy underlying Marx and Engels' body of work. This view is based on Joseph Stalin's pamphlet Dialectical and Historical Materialism, as well as textbooks issued by the Institute of Marxism–Leninism of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[20]

The substantivist ethnographic approach of economic anthropologist and sociologist Karl Polanyi bears similarities to historical materialism. Polanyi distinguishes between the formal definition of economics as the logic of rational choice between limited resources and a substantive definition of economics as the way humans make their living from their natural and social environment.[21] In The Great Transformation (1944), Polanyi asserts that both the formal and substantive definitions of economics hold true under capitalism, but that the formal definition falls short when analyzing the economic behavior of pre-industrial societies, whose behavior was more often governed by redistribution and reciprocity.[22] While Polanyi was influenced by Marx, he rejected the primacy of economic determinism in shaping the course of history, arguing that rather than being a realm unto itself, an economy is embedded within its contemporary social institutions, such as the state in the case of the market economy.[23]

Perhaps the most notable recent exploration of historical materialism is G. A. Cohen's Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence,[24] which inaugurated the school of Analytical Marxism. Cohen advances a sophisticated technological-determinist interpretation of Marx "in which history is, fundamentally, the growth of human productive power, and forms of society rise and fall according as they enable or impede that growth."[25]

Jürgen Habermas believes historical materialism "needs revision in many respects", especially because it has ignored the significance of communicative action.[26]

Göran Therborn has argued that the method of historical materialism should be applied to historical materialism as intellectual tradition, and to the history of Marxism itself.[27]

In the early 1980s, Paul Hirst and Barry Hindess elaborated a structural Marxist interpretation of historical materialism.[28]

Regulation theory, especially in the work of Michel Aglietta draws extensively on historical materialism.[29]

Spiral dynamics shows similarities to historical materialism.[how?][30]

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, much of Marxist thought was seen as anachronistic. A major effort to "renew" historical materialism comes from historian Ellen Meiksins Wood, who wrote in 1995 that, "There is something off about the assumption that the collapse of Communism represents a terminal crisis for Marxism. One might think, among other things, that in a period of capitalist triumphalism there is more scope than ever for the pursuit of Marxism’s principal project, the critique of capitalism."[31]

[T]he kernel of historical materialism was an insistence on the historicity and specificity of capitalism, and a denial that its laws were the universal laws of history...this focus on the specificity of capitalism, as a moment with historical origins as well as an end, with a systemic logic specific to it, encourages a truly historical sense lacking in classical political economy and conventional ideas of progress, and this had potentially fruitful implications for the historical study of other modes of production too.[31]

Referencing Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach, Wood says we ought to see historical materialism as “a theoretical foundation for interpreting the world in order to change it.”

Key ideas[]

Society does not consist of individuals, but expresses the sum of interrelations, the relations within which these individuals stand.

In the Marxian view, human history is like a river. From any given vantage point, a river looks much the same day after day. But actually it is constantly flowing and changing, crumbling its banks, widening and deepening its channel. The water seen one day is never the same as that seen the next. Some of it is constantly being evaporated and drawn up, to return as rain. From year to year these changes may be scarcely perceptible. But one day, when the banks are thoroughly weakened and the rains long and heavy, the river floods, bursts its banks, and may take a new course. This represents the dialectical part of Marx's famous theory of dialectical (or historical) materialism.

Historical materialism builds upon the idea of historical progress that became popular in philosophy during the Enlightenment, which asserted that the development of human society has progressed through a series of stages, from hunting and gathering, through pastoralism and cultivation, to commercial society.[34] Historical materialism rests on a foundation of dialectical materialism, in which matter is considered primary and ideas, thought, and consciousness are secondary, i.e. consciousness and human ideas about the universe result from material conditions rather than vice versa.[35]

Historical materialism springs from a fundamental underlying reality of human existence: that in order for subsequent generations of human beings to survive, it is necessary for them to produce and reproduce the material requirements of everyday life.[36] Marx then extended this premise by asserting the importance of the fact that, in order to carry out production and exchange, people have to enter into very definite social relations, or more specifically, "relations of production". However, production does not get carried out in the abstract, or by entering into arbitrary or random relations chosen at will, but instead are determined by the development of the existing forces of production.[37] How production is accomplished depends on the character of society's productive forces, which refers to the means of production such as the tools, instruments, technology, land, raw materials, and human knowledge and abilities in terms of using these means of production.[38] The relations of production are determined by the level and character of these productive forces present at any given time in history. In all societies, Human beings collectively work on nature but, especially in class societies, do not do the same work. In such societies, there is a division of labour in which people not only carry out different kinds of labour but occupy different social positions on the basis of those differences. The most important such division is that between manual and intellectual labour whereby one class produces a given society's wealth while another is able to monopolize control of the means of production and so both governs that society and lives off of the wealth generated by the labouring classes.[39]

Marx identified society's relations of production (arising on the basis of given productive forces) as the economic base of society. He also explained that on the foundation of the economic base there arise certain political institutions, laws, customs, culture, etc., and ideas, ways of thinking, morality, etc. These constitute the political/ideological "superstructure" of society. This superstructure not only has its origin in the economic base, but its features also ultimately correspond to the character and development of that economic base, i.e. the way people organize society, its relations of production, and its mode of production.[12] G.A. Cohen argues in Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence that a society's superstructure stabilizes or entrenches its economic structure, but that the economic base is primary and the superstructure secondary. That said, it is precisely because the superstructure strongly affects the base that the base selects that superstructure. As Charles Taylor puts it, "These two directions of influence are so far from being rivals that they are actually complementary. The functional explanation requires that the secondary factor tend to have a causal effect on the primary, for this dispositional fact is the key feature of the explanation."[40] It is because the influences in the two directions are not symmetrical that it makes sense to speak of primary and secondary factors, even where one is giving a non-reductionist, "holistic" account of social interaction.

To summarize, history develops in accordance with the following observations:

- Social progress is driven by progress in the material, productive forces a society has at its disposal (technology, labour, capital goods and so on)

- Humans are inevitably involved in productive relations (roughly speaking, economic relationships or institutions), which constitute our most decisive social relations. These relations progress with the development of the productive forces. They are largely determined by the division of labor, which in turn tends to determine social class.

- Relations of production are both determined by the means and forces of production and set the conditions of their development. For example, capitalism tends to increase the rate at which the forces develop and stresses the accumulation of capital.

- The relations of production define the mode of production, e.g. the capitalist mode of production is characterized by the polarization of society into capitalists and workers.

- The superstructure—the cultural and institutional features of a society, its ideological materials—is ultimately an expression of the mode of production on which the society is founded.

- Every type of state is a powerful institution of the ruling class; the state is an instrument which one class uses to secure its rule and enforce its preferred relations of production and its exploitation onto society.[citation needed]

- State power is usually only transferred from one class to another by social and political upheaval.[citation needed]

- When a given relation of production no longer supports further progress in the productive forces, either further progress is strangled, or 'revolution' must occur.[citation needed]

- The actual historical process is not predetermined but depends on class struggle, especially the elevation of class consciousness and organization of the working class.[citation needed]

Key implications in the study and understanding of history[]

Many writers note that historical materialism represented a revolution in human thought, and a break from previous ways of understanding the underlying basis of change within various human societies. As Marx puts it, "a coherence arises in human history"[41] because each generation inherits the productive forces developed previously and in turn further develops them before passing them on to the next generation. Further, this coherence increasingly involves more of humanity the more the productive forces develop and expand to bind people together in production and exchange.

This understanding counters the notion that human history is simply a series of accidents, either without any underlying cause or caused by supernatural beings or forces exerting their will on society. Historical materialism posits that history is made as a result of struggle between different social classes rooted in the underlying economic base. According to G.A. Cohen, author of Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence, the level of development of society's productive forces (i.e., society's technological powers, including tools, machinery, raw materials, and labour power) determines society's economic structure, in the sense that it selects a structure of economic relations that tends best to facilitate further technological growth. In historical explanation, the overall primacy of the productive forces can be understood in terms of two key theses:

(a) The productive forces tend to develop throughout history (the Development Thesis).

(b) The nature of the production relations of a society is explained by the level of development of its productive forces (the Primacy Thesis proper).[42]

In saying that productive forces have a universal tendency to develop, Cohen's reading of Marx is not claiming that productive forces always develop or that they never decline. Their development may be temporarily blocked, but because human beings have a rational interest in developing their capacities to control their interactions with external nature in order to satisfy their wants, the historical tendency is strongly toward further development of these capacities.

Broadly, the importance of the study of history lies in the ability of history to explain the present. John Bellamy Foster asserts that historical materialism is important in explaining history from a scientific perspective, by following the scientific method, as opposed to belief-system theories like creationism and intelligent design, which do not base their beliefs on verifiable facts and hypotheses.[43]

Trajectory of historical development[]

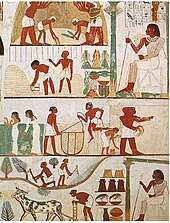

The main modes of production that Marx identified generally include primitive communism, slave society, feudalism, mercantilism, and capitalism. In each of these social stages, people interacted with nature and production in different ways. Any surplus from that production was distributed differently as well. To Marx, ancient societies (e.g. Rome and Greece) were based on a ruling class of citizens and a class of slaves; feudalism was based on nobles and serfs; and capitalism based on the capitalist class (bourgeoisie) and the working class (proletariat).

Primitive communism[]

To historical materialists, hunter-gatherer societies, also known as primitive communist societies, were structured so that economic forces and political forces were one and the same. Societies generally did not have a state, property, money, nor social classes. Due to their limited means of production (hunting and gathering) each individual was only able to produce enough to sustain themselves, thus without any surplus there is nothing to exploit. A slave at this point would only be an extra mouth to feed. This inherently makes them communist in social relations although primitive in productive forces.

Ancient mode of production[]

Slave societies, the ancient mode of production, were formed as productive forces advanced, namely due to agriculture and its ensuing abundance which led to the abandonment of nomadic society. Slave societies were marked by their use of slavery and minor private property; production for use was the primary form of production. Slave society is considered by historical materialists to be the first class society formed of citizens and slaves. Surplus from agriculture was distributed to the citizens, which exploited the slaves who worked the fields.[44]

Feudal mode of production[]

The feudal mode of production emerged from slave society (e.g. in Europe after the collapse of the Roman Empire), coinciding with the further advance of productive forces. Feudal society's class relations were marked by an entrenched nobility and serfdom. Simple commodity production existed in the form of artisans and merchants. This merchant class would grow in size and eventually form the bourgeoisie. Despite this, production was still largely for use.

Capitalist mode of production[]

The capitalist mode of production materialized when the rising bourgeois class grew large enough to institute a shift in the productive forces. The bourgeoisie's primary form of production was in the form of commodities, i.e. they produced with the purpose of exchanging their products. As this commodity production grew, the old feudal systems came into conflict with the new capitalist ones; feudalism was then eschewed as capitalism emerged. The bourgeoisie's influence expanded until commodity production became fully generalized:

The feudal system of industry, in which industrial production was monopolised by closed guilds, now no longer sufficed for the growing wants of the new markets. The manufacturing system took its place. The guild-masters were pushed on one side by the manufacturing middle class; division of labour between the different corporate guilds vanished in the face of division of labour in each single workshop.[45]

With the rise of the bourgeoisie came the concepts of nation-states and nationalism. Marx argued that capitalism completely separated the economic and political forces. Marx took the state to be a sign of this separation—it existed to manage the massive conflicts of interest which arose between the proletariat and bourgeoisie in capitalist society. Marx observed that nations arose at the time of the appearance of capitalism on the basis of community of economic life, territory, language, certain features of psychology, and traditions of everyday life and culture. In The Communist Manifesto. Marx and Engels explained that the coming into existence of nation-states was the result of class struggle, specifically of the capitalist class's attempts to overthrow the institutions of the former ruling class. Prior to capitalism, nations were not the primary political form.[46] Vladimir Lenin shared a similar view on nation-states.[47] There were two opposite tendencies in the development of nations under capitalism. One of them was expressed in the activation of national life and national movements against the oppressors. The other was expressed in the expansion of links among nations, the breaking down of barriers between them, the establishment of a unified economy and of a world market (globalization); the first is a characteristic of lower-stage capitalism and the second a more advanced form, furthering the unity of the international proletariat.[48] Alongside this development was the forced removal of the serfdom from the countryside to the city, forming a new proletarian class. This caused the countryside to become reliant on large cities. Subsequently, the new capitalist mode of production also began expanding into other societies that had not yet developed a capitalist system (e.g. the scramble for Africa). The Communist Manifesto stated:

National differences and antagonism between peoples are daily more and more vanishing, owing to the development of the bourgeoisie, to freedom of commerce, to the world market, to uniformity in the mode of production and in the conditions of life corresponding thereto.

The supremacy of the proletariat will cause them to vanish still faster. United action, of the leading civilised countries at least, is one of the first conditions for the emancipation of the proletariat.

In proportion as the exploitation of one individual by another will also be put an end to, the exploitation of one nation by another will also be put an end to. In proportion as the antagonism between classes within the nation vanishes, the hostility of one nation to another will come to an end.[49]

Under capitalism, the bourgeoisie and proletariat become the two primary classes. Class struggle between these two classes was now prevalent. With the emergence of capitalism, productive forces were now able to flourish, causing the industrial revolution in Europe. Despite this, however, the productive forces eventually reach a point where they can no longer expand, causing the same collapse that occurred at the end of feudalism:

Modern bourgeois society, with its relations of production, of exchange and of property, a society that has conjured up such gigantic means of production and of exchange, is like the sorcerer who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells. [...] The productive forces at the disposal of society no longer tend to further the development of the conditions of bourgeois property; on the contrary, they have become too powerful for these conditions, by which they are fettered, and so soon as they overcome these fetters, they bring disorder into the whole of bourgeois society, endanger the existence of bourgeois property.[45]

Communist mode of production[]

Lower-stage of communism[]

The bourgeoisie, as Marx stated in The Communist Manifesto, has "forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons—the modern working class—the proletarians."[45] Historical materialists henceforth believe that the modern proletariat are the new revolutionary class in relation to the bourgeoisie, in the same way that the bourgeoisie was the revolutionary class in relation to the nobility under feudalism.[50] The proletariat, then, must seize power as the new revolutionary class in a dictatorship of the proletariat.

Between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat.[50]

Marx also describes a communist society developed alongside the proletarian dictatorship:

Within the co-operative society based on common ownership of the means of production, the producers do not exchange their products; just as little does the labor employed on the products appear here as the value of these products, as a material quality possessed by them, since now, in contrast to capitalist society, individual labor no longer exists in an indirect fashion but directly as a component part of total labor. The phrase "proceeds of labor", objectionable also today on account of its ambiguity, thus loses all meaning. What we have to deal with here is a communist society, not as it has developed on its own foundations, but, on the contrary, just as it emerges from capitalist society; which is thus in every respect, economically, morally, and intellectually, still stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges. Accordingly, the individual producer receives back from society—after the deductions have been made—exactly what he gives to it. What he has given to it is his individual quantum of labor. For example, the social working day consists of the sum of the individual hours of work; the individual labor time of the individual producer is the part of the social working day contributed by him, his share in it. He receives a certificate from society that he has furnished such-and-such an amount of labor (after deducting his labor for the common funds); and with this certificate, he draws from the social stock of means of consumption as much as the same amount of labor cost. The same amount of labor which he has given to society in one form, he receives back in another.[51]

This lower-stage of communist society is, according to Marx, analogous to the lower-stage of capitalist society, i.e. the transition from feudalism to capitalism, in that both societies are "stamped with the birthmarks of the old society from whose womb it emerges." The emphasis on the idea that modes of production do not exist in isolation but rather are materialized from the previous existence is a core idea in historical materialism.

There is considerable debate among communists regarding the nature of this society. Some such as Joseph Stalin, Fidel Castro, and other Marxist-Leninists believe that the lower-stage of communism constitutes its own mode of production, which they call socialist rather than communist. Marxist-Leninists believe that this society may still maintain the concepts of property, money, and commodity production.[52] Other communists argue that the lower-stage of communism is just that; a communist mode of production, without commodities or money, stamped with the birthmarks of capitalism.

Higher-stage of communism[]

To Marx, the higher-stage of communist society is a free association of producers which has successfully negated all remnants of capitalism, notably the concepts of states, nationality, sexism, families, alienation, social classes, money, property, commodities, the bourgeoisie, the proletariat, division of labor, cities and countryside, class struggle, religion, ideology, and markets. It is the negation of capitalism.[2][53]

Marx made the following comments on the higher-phase of communist society:

In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaving subordination of the individual to the division of labor, and therewith also the antithesis between mental and physical labor, has vanished; after labor has become not only a means of life but life's prime want; after the productive forces have also increased with the all-around development of the individual, and all the springs of co-operative wealth flow more abundantly—only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs![51]

Warnings against misuse[]

In the 1872 Preface to the French edition of Das Kapital Vol. 1, Marx emphasized that "[t]here is no royal road to science, and only those who do not dread the fatiguing climb of its steep paths have a chance of gaining its luminous summits."[54] Reaching a scientific understanding required conscientious, painstaking research, instead of philosophical speculation and unwarranted, sweeping generalizations. Having abandoned abstract philosophical speculation in his youth, Marx himself showed great reluctance during the rest of his life about offering any generalities or universal truths about human existence or human history.

Marx himself took care to indicate that he was only proposing a guideline to historical research (Leitfaden or Auffassung), and was not providing any substantive "theory of history" or "grand philosophy of history", let alone a "master-key to history". Engels expressed irritation with dilettante academics who sought to knock up their skimpy historical knowledge as quickly as possible into some grand theoretical system that would explain "everything" about history. He opined that historical materialism and the theory of modes of production was being used as an excuse for not studying history.[55]

The first explicit and systematic summary of the materialist interpretation of history published was Engels's book Herr Eugen Dühring's Revolution in Science, written with Marx's approval and guidance, and often referred to as the Anti-Dühring. One of the polemics was to ridicule the easy "world schematism" of philosophers, who invented the latest wisdom from behind their writing desks. Towards the end of his life, in 1877, Marx wrote a letter to the editor of the Russian paper Otetchestvennye Zapisky, which significantly contained the following disclaimer:

Russia... will not succeed without having first transformed a good part of her peasants into proletarians; and after that, once taken to the bosom of the capitalist regime, she will experience its pitiless laws like other profane peoples. That is all. But that is not enough for my critic. He feels himself obliged to metamorphose my historical sketch of the genesis of capitalism in Western Europe into an historico-philosophic theory of the marche generale imposed by fate upon every people, whatever the historic circumstances in which it finds itself, in order that it may ultimately arrive at the form of economy which will ensure, together with the greatest expansion of the productive powers of social labor, the most complete development of man. But I beg his pardon. (He is both honouring and shaming me too much.)[56]

Marx goes on to illustrate how the same factors can in different historical contexts produce very different results, so that quick and easy generalizations are not really possible. To indicate how seriously Marx took research, when he died, his estate contained several cubic metres of Russian statistical publications (it was, as the old Marx observed, in Russia that his ideas gained most influence).

Insofar as Marx and Engels regarded historical processes as law-governed processes, the possible future directions of historical development were to a great extent limited and conditioned by what happened before. Retrospectively, historical processes could be understood to have happened by necessity in certain ways and not others, and to some extent at least, the most likely variants of the future could be specified on the basis of careful study of the known facts.

Towards the end of his life, Engels commented several times about the abuse of historical materialism.

In a letter to Conrad Schmidt dated 5 August 1890, he stated:

And if this man [i.e., Paul Barth] has not yet discovered that while the material mode of existence is the primum agens [first agent] this does not preclude the ideological spheres from reacting upon it in their turn, though with a secondary effect, he cannot possibly have understood the subject he is writing about. [...] The materialist conception of history has a lot of [dangerous friends] nowadays, to whom it serves as an excuse for not studying history. Just as Marx used to say, commenting on the French "Marxists" of the late 70s: "All I know is that I am not a Marxist." [...] In general, the word "materialistic" serves many of the younger writers in Germany as a mere phrase with which anything and everything is labeled without further study, that is, they stick on this label and then consider the question disposed of. But our conception of history is above all a guide to study, not a lever for construction after the manner of the Hegelian. All history must be studied afresh, the conditions of existence of the different formations of society must be examined individually before the attempt is made to deduce them from the political, civil law, aesthetic, philosophic, religious, etc., views corresponding to them. Up to now but little has been done here because only a few people have got down to it seriously. In this field we can utilize heaps of help, it is immensely big, anyone who will work seriously can achieve much and distinguish himself. But instead of this too many of the younger Germans simply make use of the phrase historical materialism (and everything can be turned into a phrase) only in order to get their own relatively scanty historical knowledge—for economic history is still in its swaddling clothes!—constructed into a neat system as quickly as possible, and they then deem themselves something very tremendous. And after that a Barth can come along and attack the thing itself, which in his circle has indeed been degraded to a mere phrase.[57]

Finally, in a letter to Franz Mehring dated 14 July 1893, Engels stated:

[T]here is only one other point lacking, which, however, Marx and I always failed to stress enough in our writings and in regard to which we are all equally guilty. That is to say, we all laid, and were bound to lay, the main emphasis, in the first place, on the derivation of political, juridical and other ideological notions, and of actions arising through the medium of these notions, from basic economic facts. But in so doing we neglected the formal side—the ways and means by which these notions, etc., come about—for the sake of the content. This has given our adversaries a welcome opportunity for misunderstandings, of which Paul Barth is a striking example.[58]

Criticism[]

Philosopher of science Karl Popper, in The Poverty of Historicism and Conjectures and Refutations, critiqued such claims of the explanatory power or valid application of historical materialism by arguing that it could explain or explain away any fact brought before it, making it unfalsifiable and thus pseudoscientific. Similar arguments were brought by Leszek Kołakowski in Main Currents of Marxism.[59]

In his 1940 essay Theses on the Philosophy of History, scholar Walter Benjamin compares historical materialism to the Turk, an 18th-century device which was promoted as a mechanized automaton which could defeat skilled chess players but actually concealed a human who controlled the machine. Benjamin suggested that, despite Marx's claims to scientific objectivity, historical materialism was actually quasi-religious. Like the Turk, wrote Benjamin, "[t]he puppet called 'historical materialism' is always supposed to win. It can do this with no further ado against any opponent, so long as it employs the services of theology, which as everyone knows is small and ugly and must be kept out of sight." Benjamin's friend and colleague Gershom Scholem would argue that Benjamin's critique of historical materialism was so definitive that, as Mark Lilla would write, "nothing remains of historical materialism [...] but the term itself".[60]

Neven Sesardic argues that historical materialism is a highly exaggerated claim. Sesardic observes that it was clear to many Marxists that the social, cultural and ideological superstructure of society was not under the control of the base but had at least some degree of autonomy. It was also clear that phenomena of the superstructure could determine part of the economic base. Thus Sesardic argues that Marxists moved from a claim of the dominance of the economic base to a scenario in which the base sometimes determines the superstructure and the superstructure sometimes determines the base, which Sesardic argues destroys their whole position. This is because this new claim, according to Sesardic, is so innocuous that no-one would deny it, whereas the old claim was very radical, as it posited the dominance of economics. Sesardic argues that Marxists should have abandoned historical materialism when its strong version became untenable, but instead they chose to water it down until it became a trivial claim.[61]

See also[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Historical materialism |

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Marx, Karl (1845). "The Illusion of the Epoch". The German Ideology. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Marx, Karl (1845). "Idealism and Materialism". The German Ideology. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ See. Charles Edward Andrew Lincoln IV, Hegelian Dialectical Analysis of U.S. Voting Laws, 42 U. Dayton L. Rev. 87 (2017).

- ^ Fromm 1961.

- ^ Woods, Alan (2016). "What Is Historical Materialism?". In Defence of Marxism. International Marxist Tendency. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Herbert A. Applebaum (1 January 1992). The Concept of Work: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern. SUNY Press. p. 431. ISBN 978-0-7914-1101-8.

- ^ Leszek Kołakowski (2005). Main Currents of Marxism: The Founders, the Golden Age, the Breakdown. W.W. Norton. p. 154-156. ISBN 978-0-393-06054-6.

- ^ William Buck Guthrie (1907). Socialism Before the French Revolution: A History. Macmillan. pp. 306–307.

- ^ Friedrich Engels. "Socialism: Utopian and Scientific". marxists.org. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Karl Marx. "Introduction to the French Edition of Engels' Socialism: Utopian and Scientific". marxists.org. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Frederick Engels. "Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (Introduction – Materialism)". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Karl Marx (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Metaphysics Research Lab, Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI), Stanford University. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Foster 1999.

- ^ Althusser, Louis (1969). For Marx. The Penguin Press. p. 59.

- ^ "Max Stirner (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Metaphysics Research Lab, Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI), Stanford University. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Welsh, John F. (2010). Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism, A new interpretation. Lexington Books. pp. 20–23.

- ^ Marx 1977.

- ^ Engels 1946.

- ^ Erich Fromm. "Marx's Conception of Man". Marxists.org. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Joseph Stalin. "Dialectical and Historical Materialism". marxists.org. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ Polanyi, K. (1944). The Great Transformation. New York. pp. 44–49.

- ^ ibid. p. 41.

- ^ Hann, Chris (29 September 2017). "Economic Anthropology". Economic Anthropology (The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology). John Wiley & Sons, 2018. pp. 1–16. doi:10.1002/9781118924396.wbiea2194. ISBN 9780470657225.

- ^ Cohen 2000.

- ^ G. A. Cohen, Karl Marx’s Theory of History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978), p. x.

- ^ Habermas, Jürgen (Autumn 1975). "Toward a Reconstruction of Historical Materialism" (PDF). Theory and Society. 2 (3): 287–300. doi:10.1007/BF00212739. S2CID 113407026. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Therborn, Göran (1980). Science, Class and Society: on the formation of Sociology and Historical Materialism. London: Verso Books.

- ^ Hirst, Paul; Hindess, Barry (1975). Pre-Capitalist Modes of Production. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- ^ Jessop, Bob (2001). "Capitalism, the Regulation Approach, and Critical Realism". In Brown, A; Fleetwood, S; Roberts, J (eds.). Critical Realism and Marxism. London: Routledge.

- ^ Douglas, Angus (16 December 2015). "Marxism versus Spiral Dynamics Integral". News24. South Africa. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Introduction", Democracy against Capitalism, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–16, 9 March 1995, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511558344.001, ISBN 978-0-521-47096-4, retrieved 20 October 2020

- ^ Marx 1993, p. 265.

- ^ Kay, Hubert (18 October 1948). "Karl Marx". Life. p. 66.

- ^ Meek 1976.

- ^ Carswell Smart, John Jamieson. "Materialism". britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Seligman 1901, p. 163.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1999). "48". Capital: Critique of Political Economy. 3. Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1999). "2". The Poverty of Philosophy. marxists.org: Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Callinicos, Alex (2011). The Revolutionary Ideas of Karl Marx. Chicago: Haymarket Books. p. 99.

- ^ Charles Taylor, “Critical Notice”, Canadian Journal of Philosophy 10 (1980), p. 330.

- ^ Marx & Engels 1968, p. 660.

- ^ Cohen, p. 134.

- ^ Foster & Clark 2008.

- ^ Harman, C. A People's History of the World. Bookmarks.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Marx, Karl (1848). The Communist Manifesto. London. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Dixon, Norm. "Marx, Engels and Lenin on the National Question". Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ "В.И. Ленин. О национальном вопросе и национальной политике" (in Russian). Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ Lenin n.d.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1848). The Communist Manifesto. London. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marx, Karl. Critique of the Gotha Programme. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marx, Karl. Critique of the Gotha Programme. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Stalin, Joseph. Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1848). The Communist Manifesto. London. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1999). "Preface". Capital: Critique of Political Economy. 1. marxists.org: Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Engels, cited approvingly by E. P. Thompson in 'The peculiarities of the English,' Socialist Register, 1965.

- ^ "Letter from Marx to Editor of the Otecestvenniye Zapisky". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ "Letters: Marx–Engels Correspondence 1890". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ^ "Letters: Marx–Engels Correspondence 1893". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 7 December 2011.

- ^ Kołakowski 1978; Popper 1957.

- ^ Lilla, Mark (25 May 1995). "The Riddle of Walter Benjamin". The New York Review of Books.

- ^ Sesardić, Neven. "Marxian Utopia." (1985), Centre for Research into Communist Economies, ISBN 0948027010, pp.14-15

Sources[]

- Benjamin, Walter. Theses on the Philosophy of History.

- Cohen, G. A. (2000) [1978]. Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence (expanded ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Engels, Friedrich (1946). "Foreword". Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy. Moscow: Progress Publishers. Retrieved 21 April 2018 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- Foster, John Bellamy (1999). Marx's Ecology: Materialism and Nature. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Foster, John Bellamy; Clark, Brett (2008). Critique of Intelligent Design: Materialism versus Creationism from Antiquity to the Present. New York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-173-3.

- Fromm, Erich (1961). "Marx's Historical Materialism". Marx's Concept of Man. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing. Retrieved 21 April 2018 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- Kołakowski, Leszek (1978). Main Currents of Marxism: Its Origins, Growth and Dissolution.

- Lenin, Vladimir Illyich (n.d.). "Критические заметки по национальному вопросу" [Critical Remarks on the National Question]. Полного собрания сочинений В. И. Ленина (in Russian). 24 (5th ed.). pp. 113–150.

- Marx, Karl (1977). Preface. A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. By Marx, Karl. Dobb, Maurice (ed.). Translated by Ryazanskaya, S. W. Moscow: Progress Publishers. Retrieved 21 April 2018 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- ——— (1993). Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy. Translated by Nicolaus, Martin. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044575-6.

- Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich (1968). Selected Works in One Volume. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Meek, Ronald L. (1976). Social Science and the Ignoble Savage. Cambridge Studies in the History and Theory of Politics. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Nirenberg, David (2013). Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-34791-3.

- Popper, Karl (1957). The Poverty of Historicism.

- Seligman, Edwin R. A. (1901). "The Economic Interpretation of History". Political Science Quarterly. 16 (4): 612–640. doi:10.2307/2140420. JSTOR 2140420.

- Thompson, E. P. (1965). "The Peculiarities of the English". Socialist Register. 2: 311–362. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

Further reading[]

This further reading section may contain inappropriate or excessive suggestions that may not follow Wikipedia's guidelines. Please ensure that only a reasonable number of balanced, topical, reliable, and notable further reading suggestions are given; removing less relevant or redundant publications with the same point of view where appropriate. Consider utilising appropriate texts as inline sources or creating a separate bibliography article. (April 2018) |

- Acton, H. B. The Illusion of the Epoch.

Critical account which focusses on incoherencies in the thought of Marx, Engels and Lenin. - Anderson, Perry (1974). Lineages of the Absolutist State.

- Aronowitz, Stanley (1981). The Crisis in Historical Materialism.

American criticism of orthodox Marxism and argument for a more radical version of historical materialism that sticks closer to Marx by changing itself to keep up with changes in the historical situation. - Blackledge, Paul (2006). Reflections on the Marxist Theory of History.

- Blackledge, Paul (2018). Vidal, Matt; Smith, Tony; Rotta, Tomás; Prew, Paul (eds.). "Historical Materialism" in Oxford Handbook on Karl Marx. The Oxford Handbook of Karl Marx. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190695545.001.0001. ISBN 9780190695545.

- Boudin, Louis B. (1907). The Theoretical System of Karl Marx. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Co.

Contains an early defence of the materialist conception of history against its critics of the day. - Childe, V. Gordon. Man Makes Himself.

Free interpretation of Marx's idea. - Cohen, Gerald. Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence.

Influential analytical Marxist interpretation. - Draper, Hal. Karl Marx's Theory of Revolution.

Captures the full subtlety of Marx's thought, but at length in four volumes. - Fleischer, Helmut. Marxism and History.

Good reply to false interpretations of Marx's view of history. - Gandler, Stefan (2015). Critical Marxism in Mexico: Adolfo Sánchez Vázquez and Bolívar Echeverría. Historical Materialism Book Series. 87. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Academic Press. ISBN 978-90-04-28468-5. ISSN 1570-1522.

- Giddens, Anthony (1981). A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism.

- Graham, Loren R. Science Philosophy and Human Behavior in the Soviet Union.

Sympathetically critical of dialectical materialism. - Habermas, Jürgen (January 1976). Communication and the Evolution of Society.

Argues historical materialism must be revised to include communicative action. - Harman, Chris. A People's History of the World.

Marxist view of history according to a leader of the International Socialist Tendency. - Harper, J. (1942). "Materialism and Historical Materialism". New Essays. 6 (2). Retrieved 21 April 2018 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

- Holt, Justin P. (2014). The Social Thought of Karl Marx. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications. doi:10.4135/9781483349381. ISBN 978-1-4129-9784-3.

Provides an introductory chapter on historical materialism. - Jakubowski, Franz. Ideology and Superstructure.

Attempts to provide an alternative to schematic interpretations of historical materialism. - Jordan, Z. A. (1967). "The Origins of Dialectical Materialism". The Evolution of Dialectical Materialism: A Philosophical and Sociological Analysis. London: Macmillan. Retrieved 21 April 2018 – via Marx Myths & Legends.

Good survey. - Mandel, Ernest. Introduction to Marxism.

Emphasizes understanding the roots of class society and the state. - ——— (1986). The Place of Marxism in History. International Institute for Research and Education. Retrieved 21 April 2018 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

Modelled on Lenin's "Three components of Marxism"[citation needed] but with a section on the reception and diffusion of Marxism in the world. - Mao Zedong. Four Essays on Philosophy.

Standard Maoist reading of Marx's materialism. - Marx, Karl (1848). Manifesto of the Communist Party.

- ——— (1869). The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon.

- ——— (1887). Engels, Friedrich (ed.). Capital: Critique of Political Economy. Volume I: The Process of Production of Capital. Translated by Moore, Samuel; Aveling, Edward. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- ——— (1895). The Class Struggles in France, 1848–1850.

- ——— (1932). Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844.

- ——— (1932). The German Ideology.

- ——— (1956). Engels, Friedrich (ed.). Capital: Critique of Political Economy. Volume II: The Process of Circulation of Capital. Translated by Lasker, I. (2nd ed.). Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- ——— (1959). Capital: Critique of Political Economy. Volume III: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole.

- ——— (1964). Hobsbawm, E. J. (ed.). Pre-Capitalist Economic Formations. Translated by Cohen, Jack. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

- ——— (1969). "Theses on Feuerbach". Marx/Engels Selected Works. Moscow: Progress Publishers. pp. 13–15.

- Mehring, Franz (1975). On Historical Materialism. Translated by Archer, Bob. London: New Park Press. Retrieved 21 April 2018 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

Classic statement by a contemporary and friend of Marx & Engels. - Novack, George (2002). Understanding History: Marxist Essays. Chippendale, New South Wales: Resistance Books. ISBN 978-1-876646-23-3. Retrieved 21 April 2018 – via Marxists Internet Archive.

Trotskyist interpretations of problems of history. - Nowak, Leszek. Property and Power: Towards a Non-Marxian Historical Materialism.

Attempts to develop a post-Stalinist interpretation of Marx's project. - Rees, John. The Algebra of Revolution.

Classical Marxist account of the philosophy of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Lukacs, and Trotsky. - Rigby, S. H. (1998). Marxism and History: A Critical Introduction (2nd ed.). Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5612-3.

- Shaw, William H. Marx's Theory of History.

Provides a short survey. - Spirkin, Alexander (1990). Fundamentals of Philosophy. Translated by Syrovatkin, Sergei. Moscow: Progress Publishers. ISBN 978-5-01-002582-3. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- Stalin, Joseph. Dialectical and Historical Materialism.

Classic statement of Stalinist doctrine. - Suchting, Wal. Marx: An Introduction.

Includes a good short introduction. - "The Materialist Conception of History". Education Bulletin. No. 1. 1979. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Therborn, Göran. Science, Class and Society.

Critical survey of the relationship between sociology and historical materialism. - Thompson, E. P. "The Poverty of Theory". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

Polemic which ridicules theorists of history who do not actually study history. - Wetter, Gustav A. Dialectical Materialism: a Historical and Systematic Survey of Philosophy in the Soviet Union.

Alternative survey. - Witt-Hansen, Johan. Historical Materialism: The Method, The Theories.

Sees historical materialism as a methodology and Das Kapital as an application of the method. - Wood, Allen W. (2004). Karl Marx. Arguments of the Philosophers (2nd ed.). Abingdon, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-31697-2.

Delves into misinterpretations of Marx including the substitution of "Historical materialism" by Lenin.

- Ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- Marxist theory

- Marxism

- Theories of history

- Materialism

- Historical materialism