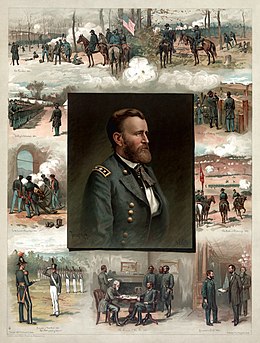

Historical reputation of Ulysses S. Grant

Hundreds of historians and biographers have written biographies and historical accounts about the life of Ulysses S. Grant and his performance in military and presidential affairs. Very few presidential reputations have shifted as dramatically as Grant's.

From the time Grant was hailed across the North as the winning general in the American Civil War his military reputation has held up fairly well. He was roundly credited as the General who "saved the Union," and although he has been the subject of some criticism over the years, this reputation largely stands intact. His presidential reputation has not always fared so well. Although his nomination as president of the United States in 1868 was considered "a foregone conclusion" and he easily won the election, his reputation as president began to suffer from congressional investigations into corruption in his administration. However, his reputation has improved in the 21st Century, for his prosecution of the Ku Klux Klan and for his protection and legal support of African Americans. He is also recognized for the creation of the first Civil Service Commission, and appointment of cabinet reformers, who prosecuted the Whiskey Ring.

After leaving office in 1877, Grant's reputation soared during his well-publicized diplomatic world tour. Accusations of Grant's alleged excessive drinking hounded him for most of his military and political career, and are still widely believed by the general public. Historians generally agree he drank occasionally but not often. At his death, he was seen as "a symbol of the American national identity and memory",[1] when millions turned out for his funeral procession in 1885.

Military and political reputation[]

| ||

|---|---|---|

18th President of the United States

Presidential elections

Post-presidency

|

||

Grant was the most successful Union General of the Civil War, defeating six Confederate armies and capturing three.[2] He was criticized over the Battle of Shiloh after the public learned that this victory came with unprecedented losses of life, and again during the Overland Campaign for the same reason. Despite the criticism, once Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox he was largely praised throughout the North as the man who had won the war.[3] Not surprisingly, general opinion of Grant in the South was much less favorable. During his presidency Grant experienced cases of fraud and governmental mismanagement, while his attempts to reunify the South with the North while trying to protect Civil Rights for African-Americans during the Reconstruction era were met with both praise and criticism, socially and historically. Grant's reputation rose again during his well-publicized world tour. While often criticized in the 20th century for not doing enough with Reconstruction efforts, and for corruption in his administration, many historians in the late 20th and 21st centuries have reevaluated Grant's performance and have largely offered more favorable assessments.[4][5]

Grant's popularity declined with congressional investigations into corruption in his administration and Custer's defeat at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. In 1877, there was bipartisan approval of Grant's peaceful handling of the electoral crisis.[6] Grant's reputation soared during his well-publicized world tour.[7] At his death, Grant was seen as "a symbol of the American national identity and memory", when millions turned out for his funeral procession in 1885 and attended the 1897 dedication of his tomb.[1] Grant's popularity increased in the years immediately after his death. At the same time, commentators and scholars portrayed his administration as the most corrupt in American history. As the popularity of the pro-Confederate Lost Cause movement increased early in the 20th century, a more negative view became increasingly common.[4]

As they had early in the Civil War, Grant's new critics charged that he was a reckless drunk, and in light of his presidency, that he was also corrupt. In the 1930s, biographer William B. Hesseltine noted that Grant's reputation deteriorated because his enemies were better writers than his friends.[8] In 1931, Frederic Paxson and Christian Bach in the Dictionary of American Biography praised Grant's military vision and his execution of that vision in defeating the Confederacy, but of his political career, the authors were less complimentary. Speaking specifically of the scandals, they wrote that "personal scandal has not touched Grant in any plausible form, but it struck so close to him and so frequently as to necessitate the vindication of his honor by admitting his bad taste in the choice of associates."[5] However, Paxson and Bach noted Grant's presidency "had some achievements, after all."[5] Paxson and Bach said Grant's presidential achievements included settling peace with Great Britain, stabilizing the nation after an attempted Johnson impeachment, he brought the nation through the "financial and moral" uneasiness of the Panic of 1873, and kept the nation from breaking up during the controversial election of 1876.[5]

Views of Grant reached new lows as he was sometimes seen as an unsuccessful president and an unskilled, if lucky, general.[7] Even for scholars with a particular concern for the plight of former slaves and Indians, Grant left a problematic legacy and, with changing attitudes toward warfare after the end of the Vietnam War, Grant's military reputation suffered again.[9]

In the 1960s Bruce Catton and T. Harry Williams began the reevaluation of Grant's military career and presented assessments of Grant as a calculating and skillful strategist and commander.[10] Catton agreed that the Union had enormous potential advantages in terms of manpower and industry, but until Grant took over in 1864, it lacked the commander who could successfully exploit that potential. Catton said, "Grant, in short, was able to use the immense advantage in numbers, and military resources, and in money which the Federal side possessed from the start. Those advantages had always been there, and what the Northern war effort had always needed was a soldier who, assuming the top command, would see to it that they were applied steadily, remorselessly, and without a break, all across the board."[11]

William S. McFeely won the Pulitzer Prize for his critical 1981 biography that credited Grant's initial efforts on civil rights, but emphasized the failure of Grant's presidency to achieve lasting progress and concluded that "he did not rise above limited talents or inspire others to do so in ways that make his administration a credit to American politics."[12] John Y. Simon in 1982 responded to McFeely: "Grant's failure as President ... lies in the failure of the Indian peace policy and the collapse of Reconstruction ... But if Grant tried and failed, who could have succeeded?"[13] Simon praised Grant's first term in office, arguing that it should be "remembered for his staunch enforcement of the rights of freedmen combined with conciliation of former Confederates, for reform in Indian policy and civil service, for successful negotiation of the Alabama Claims, and for delivery of peace and prosperity." According to Simon, the Liberal Republican revolt, the Panic of 1873, and the North's conservative retreat from Reconstruction weakened Grant's second term in office, although his foreign policy remained steady.[14]

Historians' views continued to grow more favorable since the 1990s, appreciating Grant's protection of African Americans and his peace policy towards Indians, even where those policies failed.[1] This trend continued with Jean Edward Smith's 2001 biography where he maintained that the same qualities that made Grant a success as a general carried over to his political life to make him, if not a successful president, then certainly an admirable one.[15] Smith wrote that "the common thread is strength of character—an indomitable will that never flagged in the face of adversity ... Sometimes he blundered badly; often he oversimplified; yet he saw his goals clearly and moved toward them relentlessly."[16] Brooks Simpson continued the trend in the first of two volumes on Grant in 2000, although the work was far from a hagiography.[17] H. W. Brands, in his more uniformly positive 2012 book, wrote favorably of Grant's military and political careers alike, saying:

As commanding general in the Civil War, he had defeated secession and destroyed slavery, secession's cause. As President during Reconstruction he had guided the South back into the Union. By the end of his public life the Union was more secure than at any previous time in the history of the nation. And no one had done more to produce the result than he.[18]

As Reconstruction scholar Eric Foner wrote, Brands gave "a sympathetic account of Grant's forceful and temporarily successful effort as president to crush the Ku Klux Klan, which had inaugurated a reign of terror against the former slaves." Foner criticized Grant for not sending military aid to Mississippi during the 1875 election to protect African Americans from threats of violence. According to Foner, "Grant's unwillingness to act reflected the broader Northern retreat from Reconstruction and its ideal of racial equality."[19][a]

According to historian Brooks Simpson, Grant was on "the right side of history". Simpson said, "[w]e now view Reconstruction ... as something that should have succeeded in securing equality for African-Americans, and we see Grant as supportive of that effort and doing as much as any person could do to try to secure that within realm of political reality." John F. Marszalek said, "You have to go almost to Lyndon Johnson to find a president who tried to do as much to ensure black people found freedom."[21] In 2016, Ronald C. White continued this trend with a biography that historian T. J. Stiles said, "solidifies the positive image amassed in recent decades, blotting out the caricature of a military butcher and political incompetent engraved in national memory by Jim Crow era historians."[22]

Presidency and post-presidential world tour[]

Grant was largely praised among Republicans for being a Union War hero and his nomination as president on the Republican ticket was inevitable.[23] Upon his winning the nomination for president at the 1868 National Union Republican Convention, he received all 650 votes from delegates, with no other candidate being nominated.[24] Union veterans were convinced that since he was an effective battle commander and general during the Civil War, he would be an effective President of the United States. [25] Grant won the presidency by 300,000 popular votes out of 6,000,000 voters, while he won the electoral college vote 214 to 80. [26]

According to historian John Y. Simon, had Grant served only one term of office, he would have been considered a great President by more historians, particularly noted for his successful negotiations of the Alabama Claims under his Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, his strong enforcement of civil rights for blacks, his conciliation with former Confederates, and for the delivery of a strong economy. [27] However, his second term, the Liberal Republican bolt had deprived Grant of the needed support from party intellectuals and reformers, while the Panic of 1873 devastated the national economy for years and was blamed on Grant. [27] When Grant left office in 1877 the age of the Civil War and Reconstruction ended, and his second administration foreshadowed the future administrations of Benjamin Harrison and William McKinley. [27]

Concerning his post-presidential trip around the world, historian Edwina S. Campbell said that Grant "invented key aspects of the foreign-policy role of the modern American presidency, and created an image abroad of the United States that endures to this day."[28] White viewed Grant as "an exceptional person and leader" and his presidency, although marred by corruption charges, "defended the political rights of African Americans, battled against the Ku Klux Klan and voter suppression, reimagined Indian policy, rethought the role of the federal government in a changing America, and foresaw that as the United States would now assume a larger place in world affairs, a durable peace with Great Britain would provide the nation with a major ally."[29]

"Peace policy" for Indians[]

When Grant assumed the presidency in 1869, the nation's Indian policies were in chaos, with more than 250,000 Indians on reservations being governed by 370 treaties.[30] Grant's presidency introduced a number of radical reforms while promising in his inaugural address to work toward "the proper treatment of the original occupants of this land—the Indians."[30][b] As Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Grant appointed Ely S. Parker, a Seneca Indian, a former member of his wartime staff, as the first Native American to serve in this position. With his familiarity of Indian life, Parker became the chief architect of Grant's Peace policy.[32]

Grant's plan was to replace the often corrupt political patronage system of managing Indian affairs with one that relied much less on the military and instead used religious denominations to take charge of managing the reservations. Historian Richard R. Levine argues the result was a hodgepodge of contradictions with the military and the civilian leaders battling fiercely for control of policy.[33] Jennifer Graber says the churchmen, "had come to the plains to prove that peace and kindness, rather than coercion and force, were the best methods to achieve Indian acculturation and stop Indian attacks."[34] Both Catholic and Protestant churches responded to his request for help; they were active in 70 reservations in the West. The Quaker denomination had the largest number of reservations under its supervision. Although historically committed to pacifism, the Quakers increasingly but uneasily recognized the need to use military force to keep uncooperative elements from engaging in raids.[35] The Protestant Episcopal Church brought together leaders in business and education to manage its reservation operations. Nevertheless, they became enmeshed in several scandals, including one at the Red Cloud Agency. Both the federal government and national media focused heavily on these scandals, leading to the severe damage to the reputation of the denomination as a whole.[36]

Historian Robert E. Ficken, points out that the peace policy involved assimilation with the Indians practically forced to engage in farming, rather than hunting, even though much of the reservation land was too barren for farming. The policy also led to boarding schools that have come under intense criticism since the late 20th century. Critics in addition note that reformers called for "allotment" (the breakup of an entire reservation so land would be owned in individual blocks by individual families, who could then resell it to non-Indians) without considering whether it would be beneficial. Ficken concludes that Grant's policy "contained the seeds for its own failure."[37]

Historian Cary Collins says Grant's "Peace Policy," failed in the Pacific Northwest chiefly because of sectarian competition and the priority placed on proselytizing by the religious denominations.[38] Historian Robert Keller surveying the Peace policy as a whole concludes that Grant's policy was terminated in 1882, and resulted in "cultural destruction [of] the majority of Indians."[39] Henry Waltmann argues that the president's political naïveté undercut his effectiveness. He was well-intentioned, but shortsighted, as he listened now to one faction, then to another among the generals, cabinet members, state politicians and religious advisors. The Peace Policy, concludes Waltmann, was more symbolic than substantial because Grant's actions and inactions too often contradicted his promises.[40]

Drinking[]

Allegations of drinking, whether true, exaggerated or false, have been made about Ulysses S. Grant since his day. Historian Joan Waugh notes, "... one of the most commonly asked questions from students and public alike is, "Was Ulysses S. Grant a drunk?'"[41] Charges of drinking were used against him in his presidential campaigns of 1868 and 1872.[42] In 1868 The Republican Party chose Schuyler Colfax as his running mate hoping that Colfax's reputation as a temperance reformer would neutralize the attacks.[43]

Biographer Edward Longacre says "Many of the anecdotes on which his reputation as a drunkard were built are exaggerations or fabrications ... [44] William McFeely notes that modern media typically has falsely stereotyped Grant as a drunk.[45] Contemporary stories of Grant's alleged excessive drinking were often reported by newspaper reporters during his military service in the Civil War.[c] Some of these reports are contradicted by eye witness accounts.[47] There are several other claims of Grant drinking, as he did at the isolated Fort Humboldt, which occasioned his resignation from the Army.[48] The question is how it affected his official duties. [49] Jean Edward Smith maintains, "The evidence is overwhelming that during the Vicksburg campaign he occasionally fell off the wagon. Grant took to drink, but only in private and when his command was not on the line. In a clinical sense, he may have been an "alcoholic", but overall he refrained from drink, protected from alcohol by his adjutant, Colonel John Rawlins, and especially by [his wife] Julia", maintaining that he drank when it "would not interfere with any important movement".[50]

There are no reported episodes while he was president or on the world tour, even though the media was well aware of the rumors and watched him closely. His intense dedication to staying dry proved successful and it not only resolved the alcoholism threat it made him a better decision maker and general.[citation needed] Historian James McPherson maintains Grant's self-discipline in the face of prewar drinking failures enabled him to understand and discipline others.[51] Geoffrey Perret believes that regardless of the scholarly books, however, "one thing that Americans know about Grant the soldier is that he was a hopeless drunkard."[52][53][54] However, historians overall are agreed Grant was not a drunkard – he was seldom drunk in public, and never made a major military or political decision while inebriated. Historian Lyle Dorsett, said he was probably an alcoholic, in the sense of having a strong desire for hard drink.[55][50] They emphasize he usually overcame that desire. Biographers have emphasized how "his remarkable degree of self-confidence enabled Grant to make a very great mark in the terrible American Civil War".[56]

Historians ratings[]

Throughout the 20th century, historians ranked his generalship near the top and his presidency near the bottom. In the 21st century, his military reputation is strong and above average. The rankings on his presidency have improved markedly in the 21st century from a place in the lowest quartile to a position in the middle.[19]

See also[]

- Bibliography of Ulysses S. Grant

- Bibliography of the American Civil War

- List of articles for Ulysses S. Grant

- Jesse Root Grant (father of Ulysses S. Grant)

Notes[]

- ^ In 1883, the U.S. Supreme Court overruled the Civil Rights Act of 1875 that guaranteed African Americans "full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities and privileges"; the ruling setting up a legal foundation for Jim Crow segregation throughout the South until the 1960s.[20]

- ^ Grant's religious faith also influenced his policy towards Indians, believing that the "Creator" did not place races of men on earth for the "stronger" to destroy the "weaker".[31]

- ^ Grant sometimes had meddlesome reporters expelled from a war zone, or arrested for making false reports, who often responded by perpetuating existing rumors of drunkenness,[46]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Waugh 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Bonekemper 2014, p. 431.

- ^ Brands 2012a, p. title page.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McFeely 1981, pp. 521–522.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Paxson & Bach 1931, p. 500.

- ^ Badeau 1887, p. 250.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brands 2012b, p. 45.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 14.

- ^ Rafuse 2007, p. 855, 871–874.

- ^ Rafuse 2007, p. 851.

- ^ Bruce Catton, "The Generalship of Ulysses S. Grant" (1964) in Catton, Prefaces to history (1970) p 61.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 522.

- ^ Simon 1982, p. 221.

- ^ Simon 1982, p. 253.

- ^ Weigley 2001, p. 1105.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 15.

- ^ Rafuse 2007, pp. 862–863.

- ^ Brands 2012a, p. 636.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foner 2012.

- ^ Pusey, Allen (1 March 2014). "March 1, 1875: Grant signs the Civil Rights Act". ABA Journal. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ Baumann, Nick (23 July 2015). "Ulysses S. Grant Died 130 Years Ago. Racists Hate Him, But Historians No Longer Do". Huffington Post. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ Stiles 2016.

- ^ Brands 2017, pp. 416–417.

- ^ White 2016.

- ^ Brands 2017, p. 417.

- ^ Brands 2017, p. 423.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Simon 2002, p. 253.

- ^ Campbell 2016, p. 1.

- ^ White 2016, pp. xxiv, xxvi.

- ^ Jump up to: a b White 2016, p. 487.

- ^ White 2016, p. 491.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 490–491; Simon 1982, p. 250; Smith 2001, pp. 472–473.

- ^ Richard R. Levine, . "Indian Fighters and Indian Reformers: Grant's Indian Peace Policy and the Conservative Consensus." Civil War History 31#4 (1985), pp. 329–352. doi:10.1353/cwh.1985.0049

- ^ Jennifer Graber, "If a War It May Be Called" Religion and American Culture 24.1 (2014): 36–69. online,[dead link] quote on page 36.

- ^ Joseph E. Illick, "'Some of Our Best Indians Are Friends ... ': Quaker Attitudes and Actions regarding the Western Indians during the Grant Administration." Western Historical Quarterly 2#3 (1971): 283–294.

- ^ Robert H. Keller Jr, "Episcopal Reformers and Affairs at Red Cloud Agency, 1870–1876." Nebraska History (1987) 68: 116–26.

- ^ Robert E. Ficken, "After the Treaties: Administering Pacific Northwest Indian Reservations." Oregon Historical Quarterly 106.3 (2005): 442–461.

- ^ Cary C. Collins, "A Fall From Grace: Sectarianism And The Grant Peace Policy In Western Washington Territory, 1869–1882," Pacific Northwest Forum (1995) 8#2 pp 55–77.

- ^ Robert H. Keller, American Protestantism and United States Indian Policy, 1869–82 (U of Nebraska Press, 1983) p 155.

- ^ Henry G. Waltmann, "Circumstantial Reformer: President Grant and the Indian Problem." Arizona and the West 13.4 (1971): 323–42, summarizing pp 341–42.

- ^ Waugh 2009, p. 40.

- ^ Larry J. Sabato; Howard R. Ernst, eds. (2014). Encyclopedia of American Political Parties and Elections. Infobase Publishing. p. 323.

- ^ Robert E. Dewhirst; John David Rausch, eds. (2014). Encyclopedia of the United States Congress. Infobase Publishing. p. 107.

- ^ Longacre 2006, p. 12.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 55, 77; Waugh 2009, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Mahoney 2016, p. 336.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 120, 182, 224.

- ^ Years later, Grant said, "the vice of intemperance had not a little to do with my decision to resign." Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster, 87–88.

- ^ Brands 2012a, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smith 2001, p. 231.

- ^ McPherson 2003, p. 589.

- ^ Geoffrey Perret (1997). Ulysses S. Grant: Soldier & and President. Random House. p. 432.

- ^ Waugh 2009, p. 40 "Grant's alleged alcoholism has tarnished his historical reputation"

- ^ "UCLA historian attempts to revive reputation of Union general, Reconstruction president". EurekAlert. 26 October 2009.

Yet, if Americans today remember this Civil War general and two-term U.S. president, they tend to think of a drunken, cigar-smoking military butcher

- ^ Dorsett 1983.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. xiii.

Bibliography[]

- Badeau, Adam (1887). Grant in Peace: From Appomattox to Mount McGregor. New York: D.Appleton. OCLC 558211659.

- Bonekemper, Edward H. (2014). A Victor, Not a Butcher: Ulysses S. Grant's Overlooked Military Genius. Washington: Regnery. ISBN 0-89526-062-X.

- Brands, H. W. (2012a). The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses S. Grant in War and Peace. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-53241-5.

- —— (2012b). "Presidents in Crisis Grant: Takes on the Klan". American History: 42–47.

- Campbell, Edwina S. (2016). Citizen of a Wider Commonwealth: Ulysses S. Grant's Postpresidential Diplomacy. Southern Illinois University: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 080933478X.

- Dorsett, Lyle W. (1983). "The Problem of Ulysses S. Grant's Drinking During the Civil War". Hayes Historical Journal. 4 (2): 37–49.

- Ellington, Charles G. (1987). The Trial of U.S. Grant: The Pacific Coast Years, 1852–1854. A.H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0-8706-2169-7.

- Foner, Eric (November 2, 2012). "The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses Grant in War and Peace' by H. W. Brands". The Washington Post (book review). Washington, D.C. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 2012-11-30.

- Lasner, Lynn Fabian (January 2002). "The Rise and Fall and Rise of Ulysses S. Grant". Humanities. 23 (1). Archived from the original on 2017-12-26. Retrieved 2017-07-01.

- Longacre, Edward G. (2006). General Ulysses S. Grant: The Soldier and the Man. Cambridge, Massachusetts: -Da Capo Press.

- Mahoney, Timothy R. (2016). From Hometown to Battlefield in the Civil War Era: Middle Class Life in Midwest America. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-3167-2078-3.

- McFeely, William S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. Norton. ISBN 0-393-01372-3.

- McPherson, James M. (2003). The Illustrated Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press.

- Paxson, Frederic Logan; Bach, Christian A. (1931). "Ulysses S. Grant". Dictionary of American Biography. VII. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. pp. 492–501. OCLC 4171403.

- Rafuse, Ethan S. (July 2007). "Still a Mystery? General Grant and the Historians, 1981–2006". Journal of Military History. 71 (3): 849–74. doi:10.1353/jmh.2007.0230.

- Simon, John Y (Spring 1982). "'Grant: A Biography' by William S. McFeely (book review)". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. 65 (3): 220–221. JSTOR 4635640.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

- Stiles, T. J. (October 19, 2016). "Ulysses S. Grant: New Biography of 'A Nobody From Nowhere'". The New York Times.

- Waugh, Joan (2009). U.S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3317-9.

- Weigley, Russell F. (October 2001). "'Grant' by Jean Edward Smith (book review)". The Journal of Military History. 65 (4): 1104–1105. JSTOR 2677657.

- White, Ronald C. (2016). American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-5883-6992-5.

Further reading[]

- Frantz, Edward O. A Companion to the Reconstruction Presidents 1865 – 1881 (Wiley Blackwell Companions to American History, 2014); focus on historiography.

- Longacre, Edward G. (September 9, 2007). "Was Grant a Drunk?". History News Network. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- Mannion, Richard G. "The life of a reputation: The public memory of Ulysses S. Grant" (History dissertation Georgia State University, 2012). online

- Merry, Robert W. Where They Stand: The American Presidents in the Eyes of Voters and Historians (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012).

- Waugh, Joan. "Ulysses S. Grant, Historian." in The Memory of the Civil War in American Culture, ed. Alice Fahs and Joan Waugh. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004) pp 5–38.

- Wilentz, Sean. "Return of Ulysses." The Book: An Online Review at the New Republic, (January 25, 2010). online

- Abbot, 1872. The life of General Ulysses S. Grant

- Headley, 1872. The life of Ulysses S. Grant

- King, 1914. The true Ulysses S. Grant

- Wilson, Dana, 1868. The life of Ulysses S. Grant, general of the armies of the United States

- American Civil War

- Ulysses S. Grant

- Historiography of the United States