World tour of Ulysses S. Grant

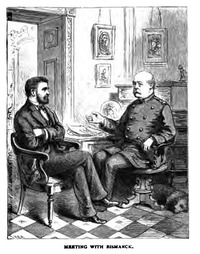

Grant with General Li Hongzhang, in China 1879, during Grant's world tour | |

| Date | 1877–1879 |

|---|---|

| Participants | Ulysses S. Grant |

| ||

|---|---|---|

18th President of the United States

Presidential elections

Post-presidency

|

||

The world tour of Ulysses S. Grant began in May 1877, only a couple of months after Grant's second presidential term had ended. After serving as a general during the Civil War, and as president for two consecutive terms during the turbulent Reconstruction Era, Grant was ready for a vacation from the years of stress that war and politics had brought him. Now in his later fifties, Grant looked forward to the tour with great enthusiasm. With his wife Julia they embarked on a long-anticipated tour, which would develop into an around the world tour, lasting more than two and a half years. The tour was filled with visits to a variety of places and prominent people, including Queen Victoria, Pope Leo XIII, Otto von Bismarck and other such dignitaries around the world. The Grants had a flexible itinerary and their visits to various countries would bring them to Paris three times during their tour. Grant was often received by cheering crowds as "General Grant" the Civil War hero in the various countries along the tour, often with official greetings and huge celebrations.

During the tour abroad, Grant was encouraged by his successor President Rutherford B. Hayes, to represent the United States in an unofficial diplomatic capacity in some cases. This involved resolving international disputes between countries – an unprecedented role for the relatively young United States. As a courtesy to Grant, his touring party was often transported to their destinations by the U.S. Navy. When he returned to the United States he was received in grand formality as he journeyed across the country. By the time Grant had completed his world tour he had brought the United States into the realm of international prominence in the eyes of much of the world.

Preparation and launch[]

Grant had assumed the presidency in 1869 with reluctance, doing so only because he did not want to leave " ... the contest for power for the next four years between mere trading politicians ... ".[1] When he finally stepped down from the presidency after eight years of hectic political life, and after years of civil war, he was relieved, and later stated, "I was never so happy in my life as the day I left the White House. I felt like a boy getting out of school." Grant was looking forward to a long vacation, anticipating the prospect of travel abroad with enthusiasm.[2] After leaving the White House, and wanting to remain in Washington to be close to daughter Nellie, who was expecting a baby, Grant accepted an invitation from his former Secretary of State, and friend, Hamilton Fish, to stay at his residence in Washington, remaining there for two months. After leaving the Fish residence in late March, Ulysses and Julia embarked on a sentimental visit to various towns and cities of their earlier days, including Cincinnati and Galena. Grant had left the White House with very little money to his name but thereafter had accumulated money given to him by his many admirers, which he invested in a mining project that yielded a profit that amounted to approximately $25,000. Grant had sacrificed his military pension when he became president.[3]

In Cincinnati, Grant was received with great fanfare and celebration and was lauded as an icon of American history, second only to George Washington. Thereafter he returned to Brown County in Ohio where he was raised and where he had not been in decades and visited with old friends.[4]

Faced with idle retirement, Grant sought to fill the void in his post-presidential life and decided to embark on a world tour with his wife, Julia – an idea he had often entertained for some years previous. He would use the money he had earned from his investment to pay for the tour. During the week before he departed on his tour he arrived at Philadelphia on May 9, and stayed in the home of his close friend, George Childs.[5] On the 14th a reception for Grant was given at the Union League Club, which concluded with a review of the First Regiment Infantry of the National Guard of Pennsylvania.[6]

The next ceremony occurred on the 16th when a procession of soldiers' orphans, all wards of the State, marched past Childs' residence while Generals Grant and Sherman stood on the steps of the house, extending their good wishes to the children as they passed. Later that day Grant was received by a group of twelve hundred veteran soldiers in Independence Hall. After the event Grant had a luncheon with Governor Hartranft at Childs' residence.[6] From there Grant stopped off in Elizabeth, New Jersey, to visit his widowed mother, Hannah.[3] Preparing for the tour, the Grants arrived in Philadelphia on May 10, 1877, and were again honored with celebrations during the week before their departure.[7]

On May 16, Grant and Julia began their world tour and left for England aboard the steamer SS Indiana voyaging across the Atlantic Ocean.[8] Among those who accompanied the Grants on the tour was John Russell Young, a journalist from the New York Herald, invited on for purposes of documenting the various visits and events as they went along.[a] Also present was Adam Badeau, U.S. Consul in London[9][b] and former general staff member for Grant during the Civil War, acting as an observer, aide and adviser.[10][c] With the United States and political life behind him, Grant's personal aspect soon changed from quiet and serious to one more friendly and talkative.[11] The prospect of a leisurely world tour and being free from the daily stresses of political life gave Grant much relief. Grant's aide, Adam Badeau, noted that any final encouragement to return to politics was now being rebuffed by an enthusiastic Grant looking forward to seeing the world.[12]

After only a couple of months into Grant's tour, the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 occurred, and he began receiving numerous letters from America with references to the overall situation, many of them expressing the general idea that a "strong man fitted to cope with the emergency" like himself, was presently lacking in the U.S. government. The crisis did not persist long, but Badeau estimated that if it had, Grant was likely to have returned out of a sense of duty. After the strike ended, the idea of entertaining a third attempt at a presidential nomination had quickly become an unlikely consideration. By March 1878, Grant wrote to Badeau, that since the railroad crisis ended "Most every letter I get from the States, like Porter's to you, asks me to remain abroad", suggesting it was best for Grant to spare himself any political trouble and inquiry.[12]

1877[]

England[]

Bound for England, the Indiana made the Atlantic crossing in eleven days, arriving at Liverpool on May 28, where large crowds greeted the ex-president and his small entourage, which included his wife Julia and nineteen-year-old son Jesse, along with New York Herald correspondent John Russell Young.[13] Grant was lauded as the "Hero of Appomattox" and the Union general who defeated the Confederacy.[14] Throughout June Grant toured England's countryside, while officials from the various townships along the way were often waiting to extend their greetings and any hospitality they could afford the touring party.[15]

While in Manchester Grant gave a memorable speech to workers who came to see him, impressed by Ulysses' moving oration on human rights. Arriving in London, Grant was guest of the Prince of Wales at Epsom Downs Racecourse, meeting with the Duke of Wellington.[16] Sunday, Grant attended the "devine service" at Westminster Abbey.[16] On June 18, Grant had breakfast with authors Matthew Arnold, Anthony Trollope, and Robert Browning.[17] Controversy ensued when Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli believed that Grant was officially just a commoner. Grant's appointed minister to London and former Attorney General, Edwards Pierrepont, now under the Hayes administration, solved the problem by maintaining that since Grant was once a President he was "always a President".[18]

On June 26, after solving matters of protocol, Grant was recognized and later introduced as "President Grant". The Grants met and dined with Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle. [19] Grant's premier visit was also the first time England was receiving a former U.S. president in a royal capacity and subsequently proper protocol in this situation had not yet been fully established.[20] With matters of protocol generally resolved, the Grants and Pierreponts were formally received by the Queen in the 520 feet (160 m) long quadrangle of the castle, while Grant was formally introduced as "President Grant" by the protocol chief.[21] At the royal dinner, Grant's son Jesse took personal exception to the arrangement that had him dining with the Royal servants, however, with Grant's encouragement, the Queen acquiesced and allowed him to sit at her table.[19] Although the Queen complained about Jesse's silent protest and critical of Julia's "funny American way", the dinner at Windsor Castle was overall a congenial event which strengthened the growing Anglo-American alliance.[22] In a speech at Liverpool Grant declared that Americans and Britons were "of one kindred, one blood, one language, and one civilization".[23]

Germany, Switzerland, Italy[]

After celebrating the Fourth of July at the American embassy in London, Grant and his party crossed the English Channel from Folkestone to Ostend, Belgium. Due to political turmoil in Paris, Grant traveled directly to Germany visiting Cologne, traveling down the Rhine to Frankfurt, and then to Heidelberg.[24] Looking forward to visiting Switzerland, Grant arrived in Geneva, the city where he once played a major role during his presidency in settling the Alabama claims with the United Kingdom.[25]

In August, Grant toured Italy, visiting Lake Maggiore and traveling down the Italian coast. Grant read Homer aloud, tracing the legendary path of Ulysses, the Homeric sojourner whose name he bore.[24]

Scotland, return to England[]

After a tour on the continent, the Grants visited Scotland arriving at Edinburgh on August 31. Grant, who had Scottish ancestry on both sides of his family, was the first US president to visit Scotland.[26] He was received by the Lord Provost of Edinburgh, becoming his guest while visiting Scotland. Grant visited the memorial of the Prince Consort, the commercial Bank of Edinburgh, its public gardens and library and the site of Sir Walter Scott's birthplace, a favorite poet of Grant who had read his poems to Julia while they were courting. Next, the Grants paid a visit to the Edinburgh Castle, where Colonel Mackenzie, of the 98th Highlanders, received Grant and escorted him about the large castle, showing him all the objects of interest.

Grant was given the freedom of Inverness, where he was greeted as a returning member of the Clan Grant.[26] On September 4, Grant traveled to Dunrobin Castle, paying his respects to the Duke of Sutherland, and was received as his guest at his home a short distance from the castle.[26] Grant declined an offer to go deer hunting, saying that he had killed wild animals twice before and had regretted it.[26] After stopping at Dornoch's horticultural fair he ventured to Thurso Castle, on the 7th, accompanied by the Duke. There Grant was received and honored by Sir Tollemache Sinclair and a guard of volunteers belonging to the local military corps. On the 13th of September, after other minor stops Grant visited Glasgow on the 13th and that afternoon was bestowed with the Freedom of the City, at Glasgow's City Hall, among the largest public buildings in the city, which was filled with spectators.[27]

After touring Scotland the Grants spent time in Southampton with their daughter Nellie and her English husband, Algernon Sartoris.[28] Grant was so well received by the Scottish people that in a speech he jested that he would run for Burgess. Grant was often praised as "the Wellington of America" and a military man, however, Grant countered that he was "always a man of peace". After touring Scotland's southern border made famous by the novels of Sir Walter Scott, Grant returned to England, where he was popularly received by working men organizations. According to historian Ronald C. White, Grant's self-effacing personality endeared him to the British people.[29]

France, Southern Italy, Malta[]

The following July Grant ferried across the English Channel and met with King Leopold II in Belgium and then Richard Wagner in Heidelberg with whom he toured the Swiss Alps. Always concerned about his budget, Grant wrote to his son Buck from London in late August inquiring about his investment. In that same letter, he expressed his strong disapproval about the rail road strikes, exclaiming that they "should have been put down by a strong hand" as a discouragement against other possible strikes.[30]

Grant and Julia next embarked for Paris arriving there during rainstorms on October 24 and checked in at the famous Hotel Bristol for five weeks. Grant for several reasons intended to make his visit to France an unofficial one.[31] France at the time was going through a major political crisis between French Republicans and Monarchists. Grant's less than favorable feelings toward Napoleon were largely known among French statesmen and military upon his arrival. Though Grant recognized Napoleon's acclaimed military genius, that he was a French Revolution war hero, he did not like the man himself, or the Bonaparte family.[32] Grant once stated,

The third Napoleon was worse than the first, the especial enemy to America and liberty.

Think of the misery he brought upon France by a war which only a madman would have declared.[33]

He contrasted further with Napoleon in that Grant fought and won more battles, commanded many more men, took more prisoners, in six years, than Napoleon had in twenty.[34] While in Paris, Grant thought the various paintings portraying Napoleon's battles were distasteful. Julia, however, did not share Grant's entire opinion of the deceased Emperor. Relations were further strained because U.S. Minister to France Elihu Washburne during the recent Franco-Prussian War once used his diplomatic immunity to protect German diplomats wanted by the French government – a position that was supported by Grant while president.[35] Given the overall situation, Grant was received coldly by Victor Hugo, whose father was once a high-ranking officer in Napoleon's army. At other times Grant was treated with polite indifference by various French military officials in Paris. Grant's dislike for Napoleon would become an issue, prompting Young to steer Grant away from possible trouble when ever possible. Young suggested that as an act of good faith they visit Napoleon's tomb, but upon coming to the scene Grant turned away. After the various and potentially unpleasant encounters with French dignitaries in Paris, Grant turned his attention to the ordinary class in French society.[36]

Aside from the political misgivings between Grant and some of the French aristocracy, journalist Young noted that Grant had friendly feelings for, and was eager to see, France, before they arrived.[37] They visited with Léon Gambetta, considered a Republican hero who was himself involved in the unrest between French Republicans and Monarchists. Grant considered him one of the greatest people he met on the tour. While in Paris the Grants made numerous visits to the Louvre to enjoy the many paintings by the masters.[38]

At November's end they traveled south to Nice where the Grants boarded USS Vandalia, a screw sloop-of-war that had been personally sent by President Hayes, for Grant's winter cruise about the Mediterranean and ultimate journey to Egypt.[39] Grant and his party departed for Italy, visiting Naples, Pompeii, Mount Vesuvius, and by December 28 arrived at Malta during gale-force winds.[40] The Hayes administration, aware of Grant's popularity in Europe, encouraged him to extend his tour and voyage around the world to strengthen American interests abroad, an unprecedented undertaking for a former president.[41]

1878[]

Egypt and Holy Land[]

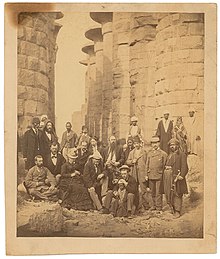

The Grants spent Christmas 1877 aboard the warship Vandalia, docked in Palermo, Italy.[42] The ship served to emphasize Grant's political importance while he was representing the United States, which was still emerging as a world power.[43] After cruising the Mediterranean, the Grants took a winter sojourn through Egypt and the Holy Land arriving in Alexandria on January 5, 1878.[44] The Khedive of Egypt, Ismail the Magnificent, allowed Grant to stay at his palace and provided a steamship to travel up the Nile River.[43] During his journey up the Nile he visited the towering minarets of Cairo and the ruins of the Karnak Temple complex in Thebes, the ancient Egyptian city.[45] Egyptian villagers welcomed Grant as "the King of America".[46] Grant's energy seemed to be endless as he explored the ancient tombs and temples.[43] He said that his weeks traveling up the Nile were "among the happiest in my life".[47] Grant, however, was critical of the filthy condition of Alexandria's poor and noted an innate "ugliness, slovenliness, filth and indolence".[44]

Grant re-boarded the Vandalia at Port Said and voyaged to the Holy Land becoming the first U.S. president to visit Jerusalem in February 1878.[48] According to Grant, the tour proved to be a "very unpleasant one". Jerusalem, during this time, was ruled by the Turkish Ottoman Empire, was run down and in poor condition, populated by 20,000 people, half of whose citizens were Jewish. Six inches of snow that covered the poorly conditioned streets did not help the travelers' impressions of the city.[49] Grant met with a delegation of American Jews who distributed relief to other suffering Jews in the Holy Land, where Grant promised to relate their message and appeal for help to Jewish leaders in the United States. While visiting the various religious sites, Julia at times was emotionally overcome with religious and spiritual sentiments, dropping to her knees in prayer in one instance, while Grant remained mostly reserved with any such expression.[47] Grant was unimpressed by Jerusalem's holy relics and agreed with Twain's assessment, regarding them as "side-shows" and "unseemly impostures".[49]

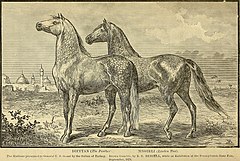

Constantinople, Athens, Italy[]

By March the Grants visited Constantinople and Greece, transported there by the sloop USS Vandalia. During his visit with Sultan Abdul Hamid II, Grant was very impressed with his stable of purebred Arabian stallions. Grant commented that the stallions would "pick up their feet like a cat, and so quickly, that no one can scarcely follow their motions". Grant was so impressed with the animals that the flattered Sultan allowed him to pick out any two he desired and take them home, which he did – a "dappled gray" and an "iron gray", which were promptly shipped back to New York. During his visit, Grant was impressed when he learned how thoroughly Ottoman officers had studied the various military campaigns under his command.[50] However, such praise and his gifts did not prevent Grant from criticizing the class and gender divisions he saw. He would later write that he believed the Turkish government treated its people "as slaves" and noting that "they have a form of government that will always repress progress and development."[49]

When the Grants arrived at Athens they were greeted by King George I of Greece, who came aboard the Vandalia and spent the afternoon with Grant. The king sought Grant's advice concerning Greece's relations with the Ottomans and Grant found himself acting in a diplomatic capacity, knowing his advice would be received as a form of American interest.[47] During their week-long visit in Athens, Grant scaled the Acropolis of Athens accompanied by Young, who noted that Grant appreciated "the greatness of the past" and was tireless during his walk through the ancient city.[51]

Thereafter, the Grants returned to Italy, arriving in Rome and departed Vandalia[51] where they were promptly approached by an emissary from Pope Leo XIII and invited to attend a ceremony with King Umberto after their visit to the Vatican. While they were visiting the Holy See, Julia's cross was blessed by the Pope. During their visit to the Vatican, the Pope chatted for a while with Grant in French, while Grant's son, Jesse, translated. Among other things, the Pope expressed his regrets that religious instruction was not allowed in public schools. While in Rome, Grant visited the Colosseum, the Arch of Titus and Arch of Constantine. However, he quickly walked by Rome's famous marble statuary almost ignoring it completely and did not seem very impressed with the many paintings, much to the disappointment of Adam Badeau, who later remarked that Grant seemed blind to the beauties of art. While in Venice, Grant made remarks about the canals, noting that they needed to be cleaned.[52]

[]

On May 7, 1878, Grant and his party returned to Paris and attended the Exposition Universelle to celebrate France's recovery from the Franco-Prussian War.[53] He commented that the French exposition was no better than the U.S. Centennial, saying the French buildings were inferior to the American buildings.[53]

In June, Grant and his party visited the Netherlands before moving on to Berlin, Germany, where he met with Chancellor Otto von Bismarck.[53][15] Having served with Philip Sheridan in various campaigns in France, Bismarck remarked that he had become great friends with Sheridan there and inquired about him. Grant replied, with complimenting praise for Sheridan, referring to him as "one of the great soldiers of the world". The two discussed military matters and in particular, the final stages of the Civil War, with Grant stressing that the Union Army fought to preserve the U.S. nation.[54] Bismarck complimented him for having saved the Union, where Grant replied, "not only save the Union, but destroy slavery". Having declined offers from several other leaders, Grant accepted Bismarck's invitation to a military review. Berlin's newspapers were filled with various stories of Grant and Bismarck's meetings while Young took account of their historic meeting for the U.S. press.[55]

Throughout July, Grant visited the Nordic countries of Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland.[56] He was welcomed by universal cheers and was received by King Christian and Queen Louise of Denmark in Copenhagen. At the dinner, he declined to drink any wine, except for a few sips of champagne when the King toasted his health. Grant had initially traveled to the area for a few weeks rest and when asked to attend a banquet in his honor he declined. He exhibited a significant knowledge of Danish history while admiring their school system and honest industry of the working people.[57]

Russia, Poland, Austria, Paris[]

Throughout the summer month of August, Grant visited St. Petersburg and Moscow in Russia. When the Grants arrived in St. Petersburg, Czar Alexander II sent out an imperial carriage that brought them to meet the Czar at his Summer Palace.[58] When Grant met the tall Czar, he noticed that he had a nervous air about him, having escaped many assassination attempts. The Czar was interested in the warfare of Native Americans and asked Grant about the future of the Plains Indians, while Grant attempted to answer him satisfactorily.[59] In St. Petersburg, as was his custom, and as a man with common roots, Grant mingled and conversed with the local people. U.S. Minister to Russia Edwin W. Stoughton escorted the Grants to see the ceremonial Russian man-of-war Peter the Great and Grant was given a seventeen-gun salute.

Grant continued his tour, visiting Warsaw and Vienna.[60] Grant met with Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I in Vienna, and in Salzburg he met with German Emperor William I. Having been abroad for fifteen months, Grant began to evaluate his tour, believing he was the first American to have traveled so many countries in that time duration. While traveling through the Austrian Alps, Grant wrote that he "missed English speaking people", and that he enjoyed traveling in Europe as much as the average American. He also observed that European countries heavily taxed their citizens to pay for massive debts and maintain standing armies, giving him a better appreciation for U.S. republican government. Grant said the U.S. people were "the most progressive, freest and richest people on earth".[61]

Crossing the Swiss Alps, Grant returned to Paris on September 25 and remained there until October 12, having covered all of Northern Europe.[60] In Bordeaux Grant was met by a message from the King of Spain, who formally requested that he honor him with a visit. Grant was never pleased much with military presentations and reviews, but the invitation was so cordial that he accepted it. The Grant party traveled as far as Biarritz, rested overnight and crossed the mountain divide into Spain the next day.[62]

Spain, Portugal, Gibraltar, Paris[]

For the remainder of October through November Grant visited Spain, Portugal and Gibraltar.[56] To avoid confusion of Grant's diplomatic status as ex-President, he was awarded the honorary rank of Captain General of the Spanish Army.[63] He was received at San Sebastian by Emilio Castelar, ex-President of the Spanish Republic. Grant was enthusiastic about their meeting and he personally thanked Castelar for all he had done for the United States.[64] After their meeting, Grant concluded their conversation by saying "Believe me, sir, the name of Castelar is especially honored in America."[62] In Vittoria, Grant was received by King of Spain Alfonso XII, at his city hall palace.[65] He was given a seat and he entered into conversation with the young King in the library. The King said he had read about Grant, and had admired his military campaigns and presidency, noting his genius and character.[66] Grant expressed sympathy on behalf of the United States for the loss of Alfonso's wife, Spanish Queen Mercedes of Orléans.[67] There was a marked contrast in their dress: Grant was in a plain black suit while the King was dressed in his captain General uniform.[68] The 20-year-old King and the 56-year-old Grant spoke freely of the burdens of being head of state.[69]

In Madrid, the Spanish capital, Grant spent a few days exploring the back alleys, whereupon, poet and Minister to Spain, James Russell Lowell, thought Grant knew Spain better than he did.[70] When Lowell took Grant to an opera, Grant could not endure the high pitched music, and exclaimed, "[h]aven't we had enough of this?" Lowell said Grant was "perfectly natural, naively puzzled to find himself a personage, and going through the ceremonies to which he is condemned with a dogged imperturbability".[61] Grant and his party visited the Royal Palace of Madrid, a mixture of Doric and Ionic architecture, however, Grant was uninterested.[71] Grant witnessed an attempted assassination of King Alfonso XII from his Hôtel de París balcony, saying he saw the flash of the assassin's pistol while Grant viewed the progress of the Royal Calvacade.[72]

In Portugal, Grant visited Lisbon where he and Julia were received by King of Portugal Don Luís I and Queen of Portugal Maria Pia of Savoy.[73] Luís I drew Grant into a private apartment away from people and discussed trade between the United States and Portugal.[74] The King believed the port of Lisbon, after a new Spanish-Portuguese railway was built, would offer the United States produce and manufactures business opportunities. Grant attended the King's royal birthday the following day.[75] Grant refused to take the Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword, an offered gift from the King, saying that although he was an ex-president, he could not accept decorations. Before leaving Portugal Grant also visited with the King's father Don Fernando.[76] On December 12, Grant once again returned to Paris.[56]

1879[]

Ireland, Marseille, Alexandria, India[]

On January 2, 1879, Grant concluded his European tour in Ireland visiting Dublin, Belfast, and Derry.[60] For the first time during the tour, Grant encountered protests, as Irish newspapers criticized Grant for not accepting a Fenian delegation advocating Irish independence, while Grant was president in 1876.[77]

Up to this point, the tour was not intended as a world tour. However, when Grant's son, Buck, offered him $60,000 to use as he needed, the tour took on world proportions. In January 1879 Grant continued in what was now a world tour. Accordingly, there were changes in Grant's touring party, with the arrival of Grant's son Fred, and former navy secretary and good friend Adolph Borie.[77]

From Queenstown, the Grants left by private ship, sailing into the Mediterranean and stopping at Marseille.[77] From there, they embarked on a seven-day journey aboard the French steamer, Labourdonnais across the Mediterranean and came to anchor outside the harbor of Alexandria on the evening of January 29. Their brief visit was without any grand reception, which suited Grant fine. They departed Egypt by train overland to the northern mouth of the Suez Canal and sailed on through to India.[78]

By March 1879 Grant had received many letters inquiring about a possible third bid for the presidency upon returning home. Many of the letters advised him to take his time on the tour, where its coverage would help him in this prospect and where he would not have to contend with reporters' questions. Grant remarked to Badeau that "almost every letter I get from the states ... ask me to remain absent. They have designs for me which I do not contemplate for myself." At this time Grant realized that he had had enough of political life and had no desire to return to its stress-filled ordeals. At the same time, it disturbed him greatly to learn of the mounting influence of Southern Democrats in Congress, while he once again feared for the welfare of African Americans in the South. However, that summer in Paris Grant had met with Blanche Bruce of Mississippi who informed the New York Times that he believed that Grant would indeed entertain a third bid for the presidency out of a sense of duty.[79][d]

At this point Grant was considering returning home to the United States when he received an offer from Secretary of the Navy Richard W. Thompson to sail aboard USS Richmond to visit India, China, and Japan by way of crossing the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal. Thompson admitted that there was a political interest involved, that the warship would accent Grant's political prominence abroad, but nonetheless convinced Grant to extend his tour, which Grant now saw as a "splendid opportunity" to return him to the U.S. with political favor just before the 1880 presidential race.[79]

Grant's touring party arrived in Bombay on February 13, traveling for a month exploring India, meeting with a number of official British hosts, and the Maharaja of Jeypore.[81] Riding atop an elephant, the Grants, accompanied by Fred Grant and Adam Borie, made their way to the Taj Mahal. Young described the building as the most beautiful in the world.[82] Julia remarked that the structure was very beautiful, but not as much as the U.S. Capitol building.[83] Grant initially viewed British rule in India as "purely selfish", yet upon observation, he acknowledged that the colonial subjects were allowed to prosper.[84] However, he took exception to some social issues, especially concerning the rights and dignity of women.[85] Overall, the Grant party showed great aversion to the governance of European powers upon their various colonies.[86][e] In Calcutta, Grant met with Viceroy Lord Lytton, whom Grant told he had admired Lytton's father's poetry, while Lytton told Grant he had studied and respected Grant's career.[88][f]

East Asia, China, Japan[]

After India, Grant toured Burma, Siam (where Grant met with King Chulalongkorn), Singapore, and Cochinchina (Vietnam).[90] Leaving Hong Kong, the Grants visited Canton, Shanghai, and Peking, China, where he criticized the autocratic attitude of Westerners living in China toward the Chinese, comparing it to that of former slave owners toward freedmen striving for independence.[91] He declined to ask for an interview with the Guangxu Emperor, but did speak with the head of government, Prince Gong, and Li Hongzhang, a leading general.[92][93] They discussed China's dispute with Japan over the Ryukyu Islands, and Grant agreed to serve as a mediator saying "any course short of national humiliation or national destruction is better than war.".[94] After crossing over to Japan on USS Richmond and meeting the Emperor Meiji, Grant, keeping his word, tried to convince Japan to make peace with the Chinese suggesting the formation of a joint commission to settle the disputed territory. Although the commission never materialized, Grant's on spot diplomacy diffused the situation.[95] Grant became the first ex-president to engage in personal diplomacy abroad.[96] Japan having the superior military, annexed the disputed islands a few weeks after Grant left the country.[97]

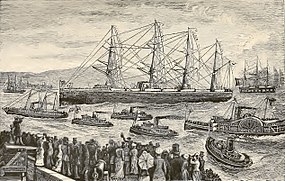

Aboard the Richmond, the Grants sailed for Yokohama nearby Tokyo, their convoy arriving July 3, where crowds waited and gave them a great welcoming. In Yokohama, harbor naval vessels from various nations stood present, while saluting with cannon fire, one ship at a time, lasting for 30 minutes. Finally, Richmond fired her volley in salute to the Japanese flag. Admirals and commanders of other fleets, Consul-general Thomas Brodhead Van Buren, and admirals of the Japanese navy were received by Grant as they came aboard Richmond.[98]

During his stay in Japan, a plot to assassinate Grant and the Emperor by Japanese hardliners was revealed but nothing ever became of the conspiracy.[99] Regardless, Japan, Grant's last visit abroad, proved to be his favorite country on the tour.[100][101] Before departing Consul-General Van Buren delivered a farewell speech for Grant. The Grant's boarded the SS City of Tokyo and departed Yokohama bay bound for San Francisco. As they sailed out of the harbor, various naval escorts fired their guns in salute. A Japanese man-of-war escorted the Grant touring party as far as the Inland Sea, also firing her guns in salute, before the City of Tokyo headed out to open sea. Young later wrote that they felt as though they were saying farewell to friends.[102]

Return to the United States[]

Forgoing a trip to Australia due to homesickness, the Grants left Japan on September 3, sailing on City of Tokio escorted by a Japanese warship, crossed the Pacific and landed in San Francisco on September 20, 1879, greeted by cheering crowds,[103] with factory whistles blowing and the cannons of Fort Point reporting. Grant was also greeted by various city officials who boarded a tugboat which came up alongside Grant's transport out in the bay, while scores of private vessels came close to get a glimpse of Grant.[104]

Grant's two-year and seven-month voyage around the world captured the popular imagination, and Republicans—especially those of the Stalwart faction—saw Grant in a new light.[105] Grant's world tour had given him the much needed foreign policy experience he had lacked when he had first entered office in 1869, giving him added political authority.[106] Grant's friend Adam Badeau was correct in his estimation, that as soon as Grant returned to the United States he would once again be absorbed by the world of politics. Among widespread support, however, Grant was immediately branded by his political enemies as a puppet for the Stalwarts. The New York Sun in its headline retorted, "Ulysses S. Grant is a man driven mad by ambition."[107]

One critical aspect of the American experience that the Grant's were forced to confront upon their return via California was the rampant white supremacy that dictated the minds of many of their fellow citizens. Having just been hosted with such good grace by the leaderships and peoples of China and then Japan as the last two destinations on their world tour, the Grant upon arriving in California were immediately confronted by anti-Chinese Anti-Asian racism from the leading echelon of Californian society. A delegate of San Francisco's Chinese community wished to present Grant with a banner and Grant was forced to receive the delegation and the banner upon federal government grounds to avoid discord with the cities and states white leadership who would not approve of it taking place on state grounds. So Grant upon his return to America was immediately confronted with the fact that white supremacy had not only maintained its force in his two-year absence; but reinforced itself by now targeting not only African Americans and Native Americans, but Asian on American soil.[108]

After a visit to Yosemite Valley, the Grants resumed their cross-country journey ultimately bound for Philadelphia, eventually arriving there on December 16, 1879.[109] The Grants stopped briefly in the Utah Territory and then Nebraska, amazed with all the new development and railroads along the way, and continued on to Galena, Illinois[g] where they were received with a large reception. There the Grants resided in a furnished home, resting there for several weeks after the initial fanfare subsided. Before leaving, Ulysses expressed his disappointment about Galena, that it once was a prosperous riverfront city, but now was reduced to a little backwater community that had been bypassed by all the new railroads.[111]

Chicago and reunion[]

Grant's next stop was Chicago for his reunion with the Army of the Tennessee, where General W. T. Sherman and some 80,000 veterans were waiting to receive him. Here Grant would soon be introduced to the famous contemporary author Mark Twain.[112] Arriving in Chicago in mid-November, the Grants once again were greeted with celebrations despite rainy weather. A huge and grand parade followed, with the Grants in front in a special horse-drawn carriage, surrounded by bodyguards consisting of officers who once served under Grant. Philip Sheridan, acting as Grand Marshal, mounted on an old warhorse, lead the entire parade, which included 3,000 veterans and 15,000 civilians.[113]

The reception and reunion was given by the Society of the Army of the Tennessee, to "General Grant", and took place at Haverly's Theatre.[114] The grand reunion was held and after a salute and review to the Army of the Tennessee, Grant was formally welcomed by Chicago's Mayor Harrison, who addressed Grant and spoke in the rotunda of the Palmer House. A formal dinner honoring Grant followed, with more than a dozen speakers, including its last speaker, Mark Twain, making homages and offering toasts. Twain later said of Grant during the speaking that he came away astonished by Grant's ability to remain calm for the duration of all the adulation. I.e. "He never moved ... for a single instant."[115]

While in Chicago Grant took time to meet with a black delegation and expressed his assurances "that all the rights of citizenship may be enjoyed by them as it is guaranteed to them already by the law and constitutional amendments". Leaving Chicago, Grant continued his home-coming journey across the country, traveling in a privately owned railroad car that was custom-made by the noted engineer George Pullman. Arriving in Louisville, Kentucky, Grant's appearance created a sensation where huge crowds endured rain to welcome Grant back. The Grants continued to Ohio, stopping in Xenia, and met with orphans of soldiers who had fallen during the Civil War. In Pittsburgh Grant met with the city's dignitaries and prominent business leaders, speaking to them in front of the governor's mansion. The largest reception however occurred in Philadelphia, where the mayor declared a holiday in Grant's honor. Here also a parade in Grant's honor was given, extending a mile, with some 350,000 spectators along its route. Ten days later Grant returned to Philadelphia, spending time alone with President Hayes where for two hours they briefed one another of national and world affairs and had "A most agreeable talk ... ".[116]

World tour map, 1879[]

Over a two and a half year period, Grant's tour took him around the world, as depicted by red lines on the world map below. At times the paths of his tour would cross, bringing him to various points of interest more than once. The cylindrical map represents the known world, excluding Arctic and Antarctic regions, 50th-90th latitudes South, and 70th-90th latitudes North, using names for countries existing in 1879. Route of tour begins in Philadelphia and proceeds east crossing the Atlantic.

J.S. Kemp, 1879

Aftermath[]

The world tour demonstrated to much of the world that the United States was an emerging world power.[43] Grant's journalist companion and fellow traveler, John Russell Young, upon their return in 1879, departed Grant's company, traveled back East, and quickly put together a two-volume account of Grant's tour around the world.[h] The books were well written and descriptive, having high-quality engravings, and were a financial success. Young reflected the self-made men coming from America's middle class that included both Young and Grant.[117]

When Grant celebrations in Philadelphia ended, Republicans interested in Grant running for the presidency, believed he had returned too soon, and encouraged him to continue traveling. At the end of December, Grant and Julia traveled south visiting Beaufort, South Carolina in January 1880 and St. Augustine, Florida, afterward voyaging to Cuba. After visiting Cuba for three weeks, Grant and Julia voyaged to Mexico in February, visiting Mexico City, where he and Julia were received by President Porfirio Díaz. After visiting Mexico, Grant returned to the United States in March visiting Galveston, Texas and finally reaching Galena, his hometown, in April.[118]

The Republican nomination for 1880 was wide open after Hayes forswore a second term and many Republicans thought that Grant was the man for the job.[105] When the Republicans met in June at their convention in Chicago, Grant was nominated by his main Stalwart backer Senator Roscoe Conkling for the Presidency. Grant followed the results but refused to attend the convention in person out of his own personal ethics.[119] The Republicans, however, had mixed feelings over Grant running for a third term, and nominated James A. Garfield for president, ending any hopes for Grant returning to the White House.[120] Grant extended his support to Garfield, the new nominee, who won the 1880 presidential election over Democratic rival Winfield Scott Hancock.[121]

In 1881, Grant traveled to Mexico City, as a proponent of international free trade, and gained a concession from the Mexican government for the construction of the Mexican Southern Railroad.[122] Díaz, Grant, and Matthias Romero were included as the company's corporate founders.[123] In October 1882, Grant persuaded Guatemala President Justo Rufino Barrios to extend the railroad line 250 miles into his country.[124]

The Civil War, presidency, and world tour had given Grant a purpose in life. His return to the United States and New York resettlement into private life, however, was not altogether easy. Grant turned to speculation on Wall Street but lost $150,000 after a stock panic in 1884. Dying of throat cancer Grant penned his Personal Memoirs published by his friend Mark Twain, that earned his family $450,000. Grant would not be able to enjoy the financial relief of his family or the popularity of his only book. Grant died on July 23, 1885.[95]

See also[]

- Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

- Bibliography of Ulysses S. Grant

Notes[]

- ^ Young would later write a two-volume work about Grant's tour – See bibliography.

- ^ Badeau was granted a leave of absence from 1877 to 1878 so he could accompany Grant on his world tour

- ^ Badeau wrote a biography about Grant after his death – See bibliography.

- ^ Grant ultimately did attempt to run for a third bid but fell short of a majority vote to get the nomination. i.e. 399 votes for Garfield, 306 for Grant.[80]

- ^ In 1878, Viceroy Lord Lytton passed the Vernacular Press Act and the Indian Arms Act that restricted the Indian press favorable to independence and licensed the purchase of arms.[87] The Indian press was critical of Lytton for sponsoring a war in Afghanistan, taking place while Grant was visiting, at the expense of assisting Indians suffering from a country-wide famine.[87]

- ^ Grant was rumored by Viceroy Lord Lytton to have been drunk and making sexual advances towards women at a dinner held in Calcutta, but historians generally discount the charges, noting Lytton did not attend the event and had left Calcutta the day before.[89]

- ^ Grant had before resided in Galena, working in a leather shop belonging to his father, Jesse Root Grant, during the months before the Civil War broke out.[110]

- ^ See: Young, 1879, in Bibliography

References[]

- ^ White 2016, p. 463.

- ^ White 2016, p. 587.

- ^ a b White 2016, pp. 590–592; Chernow 2017, pp. 861–862.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 861; White 2016, p. 587.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 590–592; Chernow 2017, pp. 861–862; Young 1879a, pp. 4–6.

- ^ a b Young 1879a, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Young 1879a, p. 4; White 2016, p. 577.

- ^ Young 1879a, p. 5; White 2016, p. 590; Chernow 2017, p. 862.

- ^ McCabe 1879, p. 56.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 852–853, 864, 866.

- ^ White 2016, p. 590; Chernow 2017, p. 862.

- ^ a b Badeau 1887, pp. 315–316.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 454–455; White 2016, p. 590; Young 1879a.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 608.

- ^ a b c Austin 2019, chapter 3.

- ^ a b White 2016, p. 591.

- ^ White 2016, p. 592.

- ^ White 2016, p. 593; Brands 2012, p. 581.

- ^ a b Chernow 2017, pp. 866–867.

- ^ Brands 2012, pp. 581–583; White 2016, p. 593; Chernow 2017, p. 866.

- ^ Brands 2012, p. 581; White 2016, p. 593.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 867.

- ^ Brands 2012, p. 582.

- ^ a b White 2016, pp. 593–594.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 724–727; White 2016, p. 593.

- ^ a b c d Thomson, Andrew (10 June 2018). "Stars and gripes: When US President Ulysses S Grant came to Scotland". BBC News. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ White 2016, p. 594; Young 1879a, pp. 79–81.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 547–548.

- ^ White 2016, p. 594.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 868.

- ^ Young 1879a, p. 129; Chernow 2017, p. 809.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 809; White 2016, p. 596.

- ^ Young 1879b, p. 166.

- ^ Packard 1880, p. 27; Remlap 1885, p. 346.

- ^ White 2016, p. 596; Young 1879a, p. 129.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 870.

- ^ Young 1879a, p. 129.

- ^ White 2016, p. 596; Chernow 2017, p. 809.

- ^ White 2016, p. 597.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 464; White 2016, pp. 589, 599; Young 1879a, p. 212.

- ^ Campbell 2016, pp. xi–xii, 2–3.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 460–465.

- ^ a b c d Chernow 2017, p. 871.

- ^ a b White 2016, p. 599.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 599–600.

- ^ White 2016, p. 600.

- ^ a b c Chernow 2017, p. 872.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 600–601; Chernow 2017, p. 872.

- ^ a b c White 2016, p. 601.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 872; White 2016, p. 601.

- ^ a b White 2016, p. 602.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 466–467; Chernow 2017, pp. 872–873.

- ^ a b c White 2016, pp. 589, 602.

- ^ Brands 2012, pp. 585–586; White 2016, p. 603.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 603–604.

- ^ a b c White 2016, pp. 589.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 875.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 589; Chernow 2017, p. 875.

- ^ Brands 2012, p. 608; Chernow 2017, pp. 875–876.

- ^ a b c White 2016, pp. 589, 606.

- ^ a b Chernow 2017, p. 876.

- ^ a b Packard 1880, pp. 444–445.

- ^ Young 1879a, p. 525.

- ^ Young 1879a, p. 526.

- ^ Young 1879a, pp. 528–529.

- ^ Young 1879a, p. 529.

- ^ Young 1879a, pp. 529–530.

- ^ Young 1879a, p. 530.

- ^ Young 1879a, pp. 530–531.

- ^ White 2016, p. 606; Chernow 2017, p. 876.

- ^ Young 1879a, p. 532.

- ^ Young 1879a, p. 533.

- ^ Young 1879a, p. 539.

- ^ Young 1879a, pp. 539–540.

- ^ Young 1879a, pp. 540–541.

- ^ Young 1879a, pp. 541–542.

- ^ a b c White 2016, pp. 606–607.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 606–607; McFeely 1981, pp. 471–473; Young 1879a, p. 589.

- ^ a b Chernow 2017, p. 877.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 617.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 589, 607–608.

- ^ Young 1879b, p. 13.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 677–678.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 473–474.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 678.

- ^ Young 2002, pp. xii–xiii.

- ^ a b Chaurasia 2002, p. 227.

- ^ White 2016, p. 607.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 878.

- ^ Brands 2012, pp. 590–591.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 612.

- ^ Brands 2012, pp. 591–592.

- ^ Austin 2019, chapter 4.

- ^ Brands 2012, pp. 593–594; Hindley 2014.

- ^ a b Hindley 2014.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 879.

- ^ Smith 2001, pp. 612n–613n; White 2016, pp. 611–612.

- ^ Young 1879b, pp. 520–521.

- ^ Young 1879b, pp. 526–527.

- ^ Austin 2019, chapter 5.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 612; Chernow 2017, p. 880.

- ^ Young 1879b, pp. 612–613.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 613; Chernow 2017, pp. 881, 883.

- ^ Brands 2012, p. 595.

- ^ a b Smith 2001, pp. 614–615.

- ^ White 2016, p. 612.

- ^ Chernow 2017, p. 884.

- ^ Austin 2019, chapter 6.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 477.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 142–143.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 885–886.

- ^ Brands 2012, p. 598; Packard 1880, p. 853.

- ^ Brands 2012, pp. 595, 598; Remlap 1885, p. 625.

- ^ Packard 1880, p. 535.

- ^ Brands 2012, p. 598.

- ^ Chernow 2017, pp. 888–889; White 2016, pp. 616–617.

- ^ Young 1879a, p. xii.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 618–619.

- ^ White 2016, p. 620.

- ^ White 2016, pp. 619, 621; Smith 2001, p. 617.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 617; White 2016, pp. 622–624.

- ^ McFeely 1981, pp. 487–488.

- ^ Simon 2008, p. 121.

- ^ McFeely 1981, p. 488.

Bibliography[]

- Austin, Ian Patrick (2019). Ulysses S. Grant and Meiji Japan, 1869-1885: Diplomatic, Strategic Thought and the Economic Context of US-Japan Relations. London and New York: Routledge.

- Badeau, Adam (1887). Grant in Peace. From Appomattox to Mount McGregor. Hartford: S. S. Scranton & Co.

- Brands, H. W. (2012). The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses S. Grant in War and Peace. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-53241-9.

- Campbell, Edwina S. (2016). Citizen of a Wider Commonwealth: Ulysses S. Grant's Postpresidential Diplomacy. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0809334780.

- Chernow, Ron (2017). Grant. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-5942-0487-6.

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of Modern India, 1707 A.D. to 2000 A.D. New Delhi: Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. ISBN 81-269-0085-7.

- Coolidge, Louis (1917). Ulysses S. Grant. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- Dana, Charles; Wilson, J.H. (1885). The life of General U.S. Grant, his early life, military achievements, and history of his civil administration; his sickness together with his tour around the world. New York, Loomis National Library Association.

- Hindley, Meredith (May–June 2014). "The Odyssey of Ulysses S. Grant". Humanities. Vol. 35 no. 3.

- McCabe, James Dabney (1879). A tour around the world by General Grant. Philadelphia: National Publishing Co.

- McFeely, William S. (1981). Grant: A Biography. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-3933-4287-1.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2001). Grant. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

- Grant, Ulysses S. (2000) [1885–1886]. Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. New York: C.L. Webster & Co.

- Packard, J. F. (1880). Grant's tour around the world; with incidents of his journey through England, Ireland, Scotland, etc. Cincinnati, O., Forshee & McMakin.

- Remlap, L. T. (1885). The life of General U.S. Grant, his early life, military achievements, and history of his civil administration, his sickness and death, together with his tour around the world. Chicago, Fairbanks & Palmer Pub. Co.

- John Y. Simon, ed. (2008). The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant: October 1, 1880-December 31, 1882. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-2776-8.

- White, Ronald C. (2016). American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-5883-6992-5.

- Young, John Russell (1879a). Around the World with General Grant, Vol. I. New York: The American News Company.

- —— (1879b). Around the World with General Grant, Vol. II. New York: The American News Company.

- —— (2002) [1879]. Michael Fellman (ed.). Around the World with General Grant. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6950-1.

Further reading[]

- Farman, Elbert E. (1904). Along the Nile with General Grant. New York: The Grafton Press.

- Hicks, W. H. (1879). General Grant's tour around the world. Chicago : Rand, McNally & co.

External links[]

Media related to World Tour of Ulysses S. Grant at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to World Tour of Ulysses S. Grant at Wikimedia Commons- "Physical Map of the World, January 2015" (PDF). University of Texas Libraries.

- Ulysses S. Grant

- 19th-century American politicians

- 1870s in the United States