History of Sindh

| History of Sindh |

|---|

|

| History of Pakistan |

| History of Pakistan |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

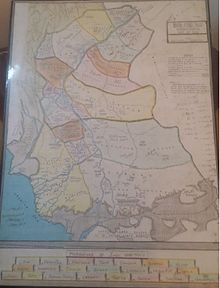

The history of Sindh or Sind (Sindhi: سنڌ جي تاريخ, Urdu: سندھ کی تاریخ) refers to the history of the modern-day Pakistani province of Sindh, as well as neighboring regions that periodically came under its sway. Sindh has longer history of dynastic rule than any other province of Pakistan due to its relatively isolated location, as compared to Punjab and Balochistan. Sindh was a cradle of civilization as the center of the ancient Indus Valley civilization, and through its long history was the seat of several dynasties that helped shape its identity.

Prehistory

Indus Valley Civilization (3300–1300 BC)

It is believed by most scholars that the earliest trace of human inhabitation in India traces to the Soan Sakaser Valley between the Indus and the Jhelum rivers. This period goes back to the first inter-glacial period in the Second Ice Age, and remnants of stone and flint tools have been found.[1][page needed]

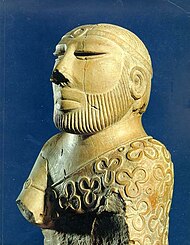

Sindh and surrounding areas contain the ruins of the Indus Valley Civilization. There are remnants of thousand-year-old cities and structures, with a notable example in Sindh being that of Mohenjo Daro. Hundreds of settlements have been found spanning an area of about a hundred miles. These ancient towns and cities had advanced features such as city-planning, brick-built houses, sewage and draining systems, as well as public baths. The people of the Indus Valley also developed a writing system, that has to this day still not been fully deciphered.[2] The people of the Indus Valley had domesticated bovines, sheep, elephants, and camels. The civilization also had knowledge of metallurgy. Gold, silver, copper, tin, and alloys were widely in use. Arts and crafts flourished during this time as well; the use of beads, seals, pottery, and bracelets are evident.[3][page needed]

Sindhu-Sauvera kingdoms (c. 1300 – c. 516 BC)

Sauvīra was an ancient kingdom of the lower Indus Valley mentioned in the Late Vedic[4] and early Buddhist literature and the Hindu epic Mahabharata. It is often mentioned alongside the Sindhu Kingdom. Its capital city was Roruka, identified with present-day Aror/Rohri in Sindh, mentioned in the Buddhist literature as a major trading center.[5] According to the Mahabharata, Jayadratha was the king of the Sindhus, Sauviras and Sivis, having conquered Sauvira and Sivi, two kingdoms close to the Sindhu kingdom.

Ancient history

Achaemenid Era (516–326 BC)

Achaemenid empire may have controlled parts of present-day Sindh as part of the province of Hindush.The territory may have corresponded to the area covering the lower and central Indus basin (present day Sindh and the southern Punjab regions of Pakistan).[9] To the north of Hindush was Gandāra (spelt as Gandāra by the Achaememids). These areas remained under Persian control until the invasion by Alexander.[10]

Alternatively, some authors consider that Hindush may have been located in the Punjab area.[11]

Hellenistic era (326–317 BC)

Alexander conquered parts of Sindh after Punjab for few years and appointed his general Peithon as governor . Alexander's death gave rise to Seleucid Empire which was defeated by the Mauryan empire.

Mauryan Era (316–180 BC)

Chandragupta Maurya, with the aid of Kautilya, had established his empire around 320 BC. The early life of Chandragupta Maurya is not clear. Kautilya took a young Chandragupta to the University at Taxila and enrolled him in order to educate him in the arts, sciences, logic, mathematics, warfare, and administration. Chankya's main task was to liberate India from Greek rule. With the help of the small Janapadas of Punjab and Sindh, he had gone on to conquer much of the North West. He then defeated the Nanda rulers in Pataliputra to capture the throne. Chandragupta Maurya fought Alexander's successor in the east, Seleucus I Nicator, when the latter invaded. In a peace treaty, Seleucus ceded all territories west of the Indus River and offered a marriage, including a portion of Bactria, while Chandragupta granted Seleucus 500 elephants.[12]

Indo-Greek era (180–90 BC)

Following a century of Mauryan rule which ended by 180 BC, the region came under the Greco-Bactrians based in what is today Afghanistan and these rulers would also convert to and proliferate Buddhism in the region. The Buddhist city of Siraj-ji-Takri is located along the western limestone terraces of the Rohri Hills in the Sukkur district of Upper Sindh, along the road that leads to Sorah. Its ruins are still visible on the top of three different mesas, in the form of stone and mud-brick walls and small mounds, whilst other architectural remains were observed along the slopes of the hills in the 1980s.

Indo Scythians (90–20 BC)

Indo Scythians ruled Sindh for a short period of time until they were thrown out by Kushans.

Kushan Empire (30–375 AD)

Kushans ruled Sindh and called the land ''Scythia'' and in this period Buddhist developed in the region.Kahu-jo-Daro stupa at mirpurkhas exhibits presence of Buddhist practices in Sindh.

Sassanian Empire (325–480 AD)

Sasanian rulers from the reign of Shapur I claimed control of the Sindh area in their inscriptions. Shapur I installed his son Narseh as "King of the Sakas" in the areas of Eastern Iran as far as Sindh.[13] Two inscriptions during the reign of Shapur II mention his control of the regions of Sindh, Sakastan and Turan.[14] Still, the exact term used by the Sasanian rulers in their inscription is Hndy, similar to Hindustan, which cannot be said for sure to mean "Sindh".[15] Al-Tabari mentioned that Shapur II built cities in Sind and Sijistan.[16][17]

Gupta Empire (480–524 AD)

Gupta empire controlled Sindh from King Samudragupta to Scandagupta (4th century AD-5th century AD)

Gurjaradesa

Gurjaradēśa, or Gurjara country, is first attested in Bana's Harshacharita (7th century AD). Its king is said to have been subdued by Harsha's father Prabhakaravardhana (died c. 605 AD).[18] The bracketing of the country with Sindha (Sindh), Lāta (southern Gujarat) and Malava (western Malwa) indicates that the region including the northern Gujarat and Rajasthan is meant.[19]

Rai Dynasty (c. 489 – 632 AD)

The Rai dynasty of Sindh was the first dynasty of sindh and at its height of power ruled much of the Northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent. The influence of the Rais extended from Kashmir in the east, Makran and Debal port (modern Karachi) in the west, Surat port in the south, and the Kandahar, Sulaiman, Ferdan and Kikanan hills in the north. It ruled an area of over 600,000 square miles (1,553,993 km2), and the dynasty reigned a period of 143 years.

Harsha Empire

Harshacharitta, a biography written by Banabhatta mentions King Harsha badly defeated the ruler of Sindh and took possession of his fortunes.[20]

Brahman dynasty (c. 632 – c. 724 AD)

It was the second dynasty of Sindh. Most of the information about Sindh's Hindu Brahman dynasty comes from the Chach Nama, a historical account of the Chach-Brahman dynasty. The Brahman dynasty were successors of the Rai dynasty. Although under Hindu kingship, Buddhism was the main religion of Sindh or at least in Southern parts of SIndh.

Medieval era

Arab Sindh (711–855 AD)

After the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, the Arab expansion towards the east reached the Sindh region beyond Persia. An initial expedition in the region launched because of the Sindhi pirate attacks on Arabs in 711–12, failed.[21][22][23]

The first clash with the Hindu kings of Sindh took place in 636 (15 A.H.) under Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab with the governor of Bahrain, Uthman ibn Abu-al-Aas, dispatching naval expeditions against Thane and Bharuch under the command of his brother, Hakam. Another brother of his, al-Mughira, was given the command of the expedition against Debal.[24] Al-Baladhuri states they were victorious at Debal but doesn't mention the results of other two raids. However, the Chach Nama states that the raid of Debal was defeated and its governor killed the leader of the raids.[25]

These raids were thought to be triggered by a later pirate attack on Umayyad ships.[26] Uthman was warned by Umar against it who said "O brother of Thaqif, you have put the worm on the wood. I swear, by Allah that if they had been smitten, I would have taken the equivalent (in men) from your families." Baladhuri adds that this stopped any more incursions until the reign of Uthman.[27]

In 712, when Mohammed Bin Qasim invaded Sindh with 8000 cavalry while also receiving reinforcements, Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf instructed him not to spare anyone in Debal. The historian al-Baladhuri stated that after conquest of Debal, Qasim kept slaughtering its inhabitants for three days. The custodians of the Buddhist stupa were killed and the temple was destroyed. Qasim gave a quarter of the city to Muslims and built a mosque there.[28] According to the Chach Nama, after the Arabs scaled Debal's walls, the besieged denizens opened the gates and pleaded for mercy but Qasim stated he had no orders to spare anyone. No mercy was shown and the inhabitants were accordingly thus slaughtered for three days, with its temple desecrated and 700 women taking shelter there enslaved. At , 6000 fighting men were massacred with their families enslaved. The massacre at Brahamanabad has various accounts of 6,000 to 26,000 inhabitants slaughtered.[29]

60,000 slaves, including 30 young royal women, were sent to al-Hajjaj. During the capture of one of the forts of Sindh, the women committed the jauhar and burnt themselves to death according to the Chach Nama.[29] S.A.A. Rizvi citing the Chach Nama, considers that conversion to Islam by political pressure began with Qasim's conquests. The Chach Nama has one instance of conversion, that of a slave from Debal converted at Qasim's hands.[30] After executing Sindh's ruler, Raja Dahir, his two daughters were sent to the caliph and they accused Qasim of raping them. The caliph ordered Qasim to be sewn up in hide of a cow and died of suffocation.[31]

Habbari Arab dynasty (855–1010)

The third dynasty, Habbari dynasty ruled the Abbasid province of Greater Sindh from 841 to 1024. The region became semi-independent under the Arab ruler Aziz al-Habbari in 841 AD, though nominally remaining part of the Caliphate.[32][33][34] The Habbaris, who were based in the city of Mansura, ruled the regions of Sindh, Makran, Turan, Khuzdar and Multan. The Umayyad Caliph made Aziz governor of Sindh and he was succeeded by his sons Umar al-Habbari I and Abdullah al-Habbari in succession while his grandson Umar al-Habbari II was ruling when the famous Arab historian Al-Masudi visited Sindh. The Habbaris ruled Sindh until 1010 when the Soomra Khafif took over Sindh. In 1026 Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi defeated Khafif, destroyed Mansura and annexed the region under the Ghaznavid rule.

Some of the territory in Sindh found itself under raids from the Turkic ruler, Mahmud Ghaznavi in 1025, who ended Arab rule of Sindh.[35] During his raids of northern Sindh, the Arab capital of Sindh, Mansura, was largely destroyed.[36]

Soomra dynasty (1011–1333)

The Soomra dynasty a Sindhi Rajput was the fourth dynasty of Sindh that ruled between early 11th century and late 1300s - initially as vassals of the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad.[37] The Soomra re-established native Sindhi rule over Sindh after a period of several centuries of Arab rule,[38] and extended their rule to Multan and Balochistan.[citation needed]

Sindhi culture experienced a revival during Soomra rule, while Arab language and traditions continued to deeply impact Sindh. Under their rule, Shia Ismailism and Sunni Sufism became widespread in Sindh and coexisted peacefully alongside one another.[37] Despite their fall, Soomra culture and traditions continued to deeply impact Sindh for the next several centuries.[39]

Samma dynasty and Delhi sultanate (1333–1520)

The Samma dynasty was a Rajput power that ruled over Sindh, parts of Kutch, parts of Punjab and Balochistan in the Indian subcontinent from c. 1351 to c. 1524 AD, with their capital at Thatta as the fifth dynasty of Sindh; before being replaced by the Arghun dynasty. Under the Samma dynasty, Sindh was a vassal of the Delhi sultanate, following the conquest by Firuz Shah Tughlaq, the Turkic ruler of Delhi in 1361–62. Sindh remained a vassal of Delhi until the rule of the Turkic Sayyid dynasty in Delhi.

The Samma dynasty has left its mark in Sindh with magnificent structures including the Makli Necropolis of its royals in Thatta.[40][41]

Arghun dynasty (1520–1554)

The Arghun dynasty were a dynasty of either Mongol,[42] Turkic or Turco-Mongol ethnicity,[43] who ruled over the area between southern Afghanistan, and Sindh from the late 15th century to the early 16th century as the Sindh's sixth dynasty. They claimed their descent and name from Ilkhanid-Mongol Arghun Khan.[44]

Tarkhan dynasty (1554–1591)

Arghun rule was divided into two branches: the Arghun branch of Dhu'l-Nun Beg Arghun that ruled until 1554, and the Tarkhan branch of Muhammad 'Isa Tarkhan that ruled until 1591 as the seventh dynasty of Sindh.[43]

Early modern era

Mughal Era (1591–1701)

Dynasties came and went for several hundred years until the late 16th century, when Sindh was brought into the Mughal Empire by Akbar, himself born in the Hindu Rajput kingdom of Umerkot in Sindh. Mughal rule from their provincial capital of Thatta was to last in lower Sindh until the early 18th century. Upper Sindh was a different picture, however, with the indigenous Kalhora dynasty holding power, consolidating their rule until the mid-18th century, when the Persian sacking of the Mughal throne in Delhi allowed them to grab the rest of Sindh. Akbar, unlike his predecessors, was renowned for his religious freedom.

Early in his reign in 1563, the emperor abolished taxes on Hindu pilgrims and allowed Hindu temples to be built and repaired. In 1564 he abolished the jizya, the tax paid by all non-Muslims.

Kalhora dynasty (1701–1783)

The Kalhora dynasty was a Sunni dynasty based in Sindh.[45][46][47] This dynasty as the eighth dynasty of Sindh ruled Sindh and parts of the Punjab region between 1701 and 1783 from their capital of Khudabad, before shifting to Hyderabad from 1768 onwards.

Kalhora rule of Sindh began in 1701 when Mian Yar Muhammad Kalhoro was invested with title of Khuda Yar Khan and was made governor of Upper Sindh sarkar by royal decree of the Mughals.[48] Later, he was made governor of Siwi through imperial decree. He founded a new city Khudabad after he obtained from Aurangzeb a grant of the track between the Indus and the Nara and made it the capital of his kingdom. Thenceforth, Mian Yar Muhammad became one of the imperial agents or governors. Later he extended his rule to Sehwan and Bukkur and became sole ruler of Northern and central Sindh except Thatto which was still under the administrative control of Mughal Empire.[48]

The Kalhora dynasty produced four powerful rulers namely, Mian Nasir Muhammad, Mian Yar Muhammad, Mian Noor Muhammad and Mian Ghulam Shah.

Talpur dynasty (1783–1843)

The Talpur dynasty (Sindhi: ٽالپردور; Urdu: سلسله تالپور) were rulers based in Sindh, in what is now the modern-day Pakistan. It was the ninth and last of the dynasties of Sindh. Four branches of the dynasty were established following the defeat of the Kalhora dynasty at the Battle of Halani in 1743. one ruled lower Sindh from the city of Hyderabad, another ruled over upper Sindh from the city of Khairpur, a third ruled around the eastern city of Mirpur Khas, and a fourth was based in Tando Muhammad Khan. The Talpurs were ethnically Baloch. They ruled from 1783, until 1843, when they were in turn defeated by the British at the Battle of Miani and Battle of Dubbo.

Modern era

British Rule (1843–1947)

The British conquered Sindh in 1843. General Charles Napier is said to have reported victory to the Governor General with a one-word telegram, namely "Peccavi" – or "I have sinned" (Latin).

The British had two objectives in their rule of Sindh: the consolidation of British rule and the use of Sindh as a market for British products and a source of revenue and raw materials. With the appropriate infrastructure in place, the British hoped to utilise Sindh for its economic potential.[49]

The British incorporated Sindh, some years later after annexing it, into the Bombay Presidency. Distance from the provincial capital, Bombay, led to grievances that Sindh was neglected in contrast to other parts of the Presidency. The merger of Sindh into Punjab province was considered from time from time but was turned down because of British disagreement and Sindhi opposition, both from Muslims and Hindus, to being annexed to Punjab.[49]

The British desired to increase their profitability from Sindh and carried out extensive work on the irrigation system in Sindh, for example, the Jamrao Canal project. However, the local Sindhis were described as both eager and lazy and for this reason, the British authorities encouraged the immigration of Punjabi peasants into Sindh as they were deemed more hard-working. Punjabi migrations to Sindh paralleled the further development of Sindh's irrigation system in the early 20th century. Sindhi apprehension of a ‘Punjabi invasion’ grew.[49]

In his backdrop, desire for a separate administrative status for Sindh grew. At the annual session of the Indian National Congress in 1913, a Sindhi Hindu put forward the demand for Sindh's separation from the Bombay Presidency on the grounds of Sindh's unique cultural character. This reflected the desire of Sindh's predominantly Hindu commercial class to free itself from competing with the more powerful Bombay's business interests.[49] Meanwhile, Sindhi politics was characterised in the 1920s by the growing importance of Karachi and the Khilafat Movement.[50] A number of Sindhi pirs, descendants of Sufi saints who had proselytised in Sindh, joined the Khilafat Movement, which propagated the protection of the Ottoman Caliphate, and those pirs who did not join the movement found a decline in their following.[51] The pirs generated huge support for the Khilafat cause in Sindh.[52] Sindh came to be at the forefront of the Khilafat Movement.[53]

Although Sindh had a cleaner record of communal harmony than other parts of India, the province's Muslim elite and emerging Muslim middle class demanded separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency as a safeguard for their own interests. In this campaign, local Sindhi Muslims identified ‘Hindu’ with Bombay instead of Sindh. Sindhi Hindus were seen as representing the interests of Bombay instead of the majority of Sindhi Muslims. Sindhi Hindus, for the most part, opposed the separation of Sindh from Bombay.[49] Sindh's Hindu and Muslim communities lived in close proximity to each other and extensively influenced each other's culture. Scholars have discussed that it was found that Hindu practices in Sindh differed from orthodox Hinduism in the rest of India. Hinduism in Sindh was to a large extent influenced by Islam, Sikhism and Sufism. Sindh's religious syncretism was a result of Sufism. Sufism was a vital component of Sindhi Muslim identity and Sindhi Hindus, more than Hindus in any other part of India, came under the influence of Sufi thought and practices and the majority of them were murids (followers) of Sufi Muslim saints.[54]

However, both the Muslim landed elite, waderas, and the Hindu commercial elements, banias, collaborated in oppressing the predominantly Muslim peasantry of Sindh who were economically exploited. In Sindh's first provincial election after its separation from Bombay in 1936, economic interests were an essential factor of politics informed by religious and cultural issues.[55] Due to British policies, much land in Sindh was transferred from Muslim to Hindu hands over the decades.[56] Religious tensions rose in Sindh over the Sukkur Manzilgah issue where Muslims and Hindus disputed over an abandoned mosque in proximity to an area sacred to Hindus. The Sindh Muslim League exploited the issue and agitated for the return of the mosque to Muslims. Consequentially, a thousand members of the Muslim League were imprisoned. Eventually, due to panic the government restored the mosque to Muslims.[55]

The separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency triggered Sindhi Muslim nationalists to support the Pakistan Movement. Even while the Punjab and North-West Frontier Province were ruled by parties hostile to the Muslim League, Sindh remained loyal to Jinnah.[57] Although the prominent Sindhi Muslim nationalist G.M. Syed left the All India Muslim League in the mid-1940s and his relationship with Jinnah never improved, the overwhelming majority of Sindhi Muslims supported the creation of Pakistan, seeing in it their deliverance.[50] Sindhi support for the Pakistan Movement arose from the desire of the Sindhi Muslim business class to drive out their Hindu competitors.[58] The Muslim League's rise to becoming the party with the strongest support in Sindh was in large part linked to its winning over of the religious pir families. Although the Muslim League had previously fared poorly in the 1937 elections in Sindh, when local Sindhi Muslim parties won more seats,[59] the Muslim League's cultivation of support from the pirs and saiyids of Sindh in 1946 helped it gain a foothold in the province.[60]

Partition (1947)

In 1947, violence did not constitute a major part of the Sindhi partition experience, unlike in Punjab. There were very few incidents of violence on Sindh, in part due to the Sufi-influenced culture of religious tolerance and in part that Sindh was not divided and was instead made part of Pakistan in its entirety. Sindhi Hindus who left generally did so out of a fear of persecution, rather than persecution itself, because of the arrival of Muslim refugees from India. Sindhi Hindus differentiated between the local Sindhi Muslims and the migrant Muslims from India. A large number of Sindhi Hindus travelled to India by sea, to the ports of Bombay, Porbandar, Veraval and Okha.[61]

References

- ^ Singh 1988.

- ^ Singh 1988, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Panikkar 1964.

- ^ Michael Witzel (1987), "On the localisation of Vedic texts and schools (Materials on Vedic Śākhās, 7)" in G. Pollet (ed.), India and the Ancient world. History, Trade and Culture before A.D. 650

- ^ Derryl N. MacLean (1989), Religion and Society in Arab Sind, p.63

- ^ Philip's Atlas of World History (1999)

- ^ O'Brien, Patrick Karl (2002). Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780195219210.

- ^ Barraclough, Geoffrey (1989). The Times Atlas of World History. Times Books. p. 79. ISBN 9780723009061.

- ^ M. A. Dandamaev. "A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire" p 147. BRILL, 1989 ISBN 978-9004091726

- ^ Rafi U. Samad, The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing, 2011, p. 33 ISBN 0875868592

- ^ "Hidus could be the areas of Sindh, or Taxila and West Punjab." in Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. 2002. p. 204. ISBN 9780521228046.

- ^ Thorpe 2009, p. 33.

- ^ Senior, R.C. (1991). "The Coinage of Sind from 250 AD up to the Arab Conquest" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society. 129 (June–July 1991): 3–4.

- ^ Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. p. 17. ISBN 9780857716668.

- ^ Schindel, Nikolaus; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj; Pendleton, Elizabeth (2016). The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: adaptation and expansion. Oxbow Books. pp. 126–129. ISBN 9781785702105.

- ^ Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. p. 18. ISBN 9780857716668.

- ^ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. p. 83. ISBN 9781474400305.

- ^ Puri 1986, p. 9.

- ^ Goyal, Shankar (1991), "Recent Historiography of the Age of Harṣa", Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 72/73 (1/4): 331–361, JSTOR 41694902

- ^ Krishnamoorthy, K. (1982). Banabhatta (Sanskrit Writer). Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-7201-674-6.

- ^ Tandle, pp. 269, 270.

- ^ El Hareir, Idris; Mbaye, Ravane (2012), The Spread of Islam Throughout the World, UNESCO, p. 602, ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2

- ^ "History of India". indiansaga.com. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ El Hareir, Idris; Mbaye, Ravane (2012), The Spread of Islam Throughout the World, UNESCO, pp. 601–2, ISBN 978-92-3-104153-2

- ^ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1976), Readings in political history of India, ancient, mediaeval, and modern, B.R. Pub. Corp., on behalf of Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies, p. 216

- ^ Tripathi 1967, p. 337.

- ^ Asif 2016, p. 35.

- ^ Wink 2002, p. 203.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Classical age, by R. C. Majumdar, p. 456

- ^ Asif 2016, p. 117.

- ^ Suvorova, Anna (2004), Muslim Saints of South Asia: The Eleventh to Fifteenth Centuries, Routledge, p. 218, ISBN 978-1-134-37006-1

- ^ P. M. (M.S. Asimov, Vadim Mikhaĭlovich Masson, Ahmad Hasan Dani, Unesco, Clifford Edmund Bosworth), The History of Civilizations of Central Asia, UNESCO, 1999, ISBN 81-208-1595-5, ISBN 978-81-208-1595-7 pg 293-294.

- ^ P. M. Nagendra Kumar Singh), Muslim Kingship in India, Anmol Publications, 1999, ISBN 81-261-0436-8, ISBN 978-81-261-0436-9 pg 43-45.

- ^ P. M. Derryl N. Maclean), Religion and society in Arab Sindh, Published by Brill, 1989, ISBN 90-04-08551-3, ISBN 978-90-04-08551-0 pg 140-143.

- ^ Abdulla, Ahmed (1987). An Observation: Perspective of Pakistan. Tanzeem Publishers.

- ^ Habib, Irfan (2011). Economic History of Medieval India, 1200-1500. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-2791-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Siddiqui, Habibullah. "The Soomras of Sindh: their origin, main characteristics and rule – an overview (general survey) (1025 – 1351 AD)" (PDF). Literary Conference on Soomra Period in Sindh.

- ^ International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics. Department of Linguistics, University of Kerala. 2007.

- ^ The Herald. Pakistan Herald Publications. 1992.

- ^ Census Organization (Pakistan); Abdul Latif (1976). Population Census of Pakistan, 1972: Larkana. Manager of Publications.

- ^ Population Census of Pakistan, 1972: Jacobabad

- ^ Davies, p. 627

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bosworth, "New Islamic Dynasties," p. 329

- ^ The Travels of Marco Polo - Complete (Mobi Classics) By Marco Polo, Rustichello of Pisa, Henry Yule (Translator)

- ^ Verkaaik, Oskar (2004). Migrants and Militants: Fun and Urban Violence in Pakistan. Princeton University Press. pp. 94, 99. ISBN 978-0-69111-709-6.

The area of the Hindu-built mansion Pakka Qila was built in 1768 by the Kalhora kings, a local dynasty of Arab origin that ruled Sindh independently from the decaying Moghul Empire beginning in the mid-eighteenth century.

- ^ Ansari, Sarah F. D. (1992). Sufi Saints and State Power: The Pirs of Sind, 1843-1947. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-52140-530-0.

Another key to Kalhora 'success' lay in their strengthening of the Baluchi element in Sind.

- ^ Pakistan Quarterly. As the Kalhoras were also a Baluch Dynasty. 1958.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sarah F. D. Ansari (31 January 1992). Sufi Saints and State Power: The Pirs of Sind, 1843-1947. Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–34. ISBN 978-0-521-40530-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Roger D. Long; Gurharpal Singh; Yunas Samad; Ian Talbot (8 October 2015), State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security, Routledge, pp. 102–, ISBN 978-1-317-44820-4

- ^ Jump up to: a b I. Malik (3 June 1999), Islam, Nationalism and the West: Issues of Identity in Pakistan, Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 56–, ISBN 978-0-230-37539-0

- ^ Gail Minault (1982), The Khilafat Movement: Religious Symbolism and Political Mobilization in India, Columbia University Press, pp. 105–, ISBN 978-0-231-05072-2

- ^ Ansari 1992, p. 77 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFAnsari1992 (help)

- ^ Pakistan Historical Society (2007), Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, Pakistan Historical Society., p. 245

- ^ Priya Kumar & Rita Kothari (2016) Sindh, 1947 and Beyond, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 39:4, 775, DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jalal 2002, p. 415

- ^ Amritjit Singh; Nalini Iyer; Rahul K. Gairola (15 June 2016), Revisiting India's Partition: New Essays on Memory, Culture, and Politics, Lexington Books, pp. 127–, ISBN 978-1-4985-3105-4

- ^ Khaled Ahmed (18 August 2016), Sleepwalking to Surrender: Dealing with Terrorism in Pakistan, Penguin Books Limited, pp. 230–, ISBN 978-93-86057-62-4

- ^ Veena Kukreja (24 February 2003), Contemporary Pakistan: Political Processes, Conflicts and Crises, SAGE Publications, pp. 138–, ISBN 978-0-7619-9683-5

- ^ Ansari 1992, p. 115. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFAnsari1992 (help)

- ^ Ansari 1992, p. 122. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFAnsari1992 (help)

- ^ Priya Kumar & Rita Kothari (2016) Sindh, 1947 and Beyond, South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 39:4, 776-777, DOI: 10.1080/00856401.2016.1244752

Sources

- Ansari, Sarah F. D. (1992), Sufi Saints and State Power: The Pirs of Sind, 1843-1947, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-40530-0

- Asif, Manan Ahmed (2016), A Book of Conquest, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-66011-3

- Chattopadhyaya, Brajadulal (2003), Studying Early India: Archaeology, Texts, and Historical Issues, Orient Blackswan, ISBN 978-81-7824-143-2

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002), History of Ancient India: Earliest Times to 1000 A. D., Atlantic Publishers & Dist, ISBN 978-81-269-0027-5

- Jalal, Ayesha (4 January 2002), Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-59937-0

- Panikkar, K. M. (1964) [first published 1947], A Survey of Indian History, Asia Publishing House

- Singh, Mohinder, ed. (1988), History and Culture of Panjab, Atlantic Publishers & Distri, GGKEY:JB4N751DFNN

- Thorpe, Showick Thorpe Edgar (2009), The Pearson General Studies Manual 2009, 1/e, Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-81-317-2133-9

- Tripathi, Rama Shankar (1967), History of Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0018-2

- Wink, André (2002), Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam 7Th-11th Centuries, BRILL, ISBN 0-391-04173-8

- Wynbrandt, James (2009), A Brief History of Pakistan, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-6184-6

- History of Sindh