History of animation

The history of animation started long before the development of cinematography. Humans have probably attempted to depict motion as far back as the paleolithic period. Much later, shadow play and the magic lantern (since circa 1659) offered popular shows with projected images on a screen, moving as the result of manipulation by hand and/or minor mechanics. In 1833, the stroboscopic disc (better known as the phenakistiscope) introduced the stroboscopic principles of modern animation, which decades later would also provide the basis for cinematography. Between 1895 and 1920, during the rise of the cinematic industry, several different animation techniques were developed, including stop-motion with objects, puppets, clay or cutouts, and drawn or painted animation. Hand-drawn animation, mostly animation painted on cels, was the dominant technique throughout most of the 20th century and became known as traditional animation.

Around the turn of the millennium, computer animation became the dominant animation technique in most regions (while Japanese anime and European hand-drawn productions continue to be very popular). Computer animation is mostly associated with a three-dimensional appearance with detailed shading, although many different animation styles have been generated or simulated with computers. Some productions may be recognized as Flash animation, but in practice, computer animation with a relatively two-dimensional appearance, stark outlines and little shading, will generally be considered "traditional animation". For instance, the first feature movie made on computers, without a camera, is The Rescuers Down Under (1990), but its style can hardly be distinguished from cel animation.

This article details the history of animation which looks like drawn or painted animation, regardless of the underlying technique.

Early approaches to motion in art[]

There are several examples of early sequential images that may seem similar to series of animation drawings. Most of these examples would only allow an extremely low frame rate when they are animated, resulting in short and crude animations that are not very lifelike. However, it's very unlikely that these images were intended to be somehow viewed as an animation. It is possible to imagine technology that could have been used in the periods of their creation, but no conclusive evidence in artifacts or descriptions have been found. It is sometimes argued that these early sequential images are too easily interpreted as "pre-cinema" by minds accustomed to film, comic books and other modern sequential images, while it is uncertain that the creators of these images envisioned anything like it.[1] Fluid animation needs a proper breakdown of a motion into the separate images of very short instances, which could hardly be imagined before modern times.[2] Measuring instances shorter than a second first became possible with instruments developed in the 1850s.[3]

Early examples of attempts to capture the phenomenon of motion into a still drawing can be found in paleolithic cave paintings, where animals are sometimes depicted with multiple legs in superimposed positions or in series that can be interpreted as one animal in different positions.[4] It has been claimed that these superimposed figures were intended for a form of animation with the flickering light of the flames of a fire or of a passing torch, alternately illuminating different parts of the painted rock wall, revealing different parts of the motion.[5][6]

Archaeological finds of small paleolithic discs with a hole in the middle and drawings on both sides have been claimed to be a kind of prehistoric thaumatropes that show motion when spun on a string.[5][7]

A 5,200-year-old pottery bowl discovered in Shahr-e Sukhteh, Iran has five sequential images painted around it that seem to show phases of a goat leaping up to nip at a tree.[8][9]

An Egyptian mural approximately 4000 years old, found in the tomb of Khnumhotep at the Beni Hassan cemetery, features a very long series of images that apparently depict the sequence of events in a wrestling match.[10]

The Parthenon Frieze (circa 400 BCE) has been described as displaying analysis of motion and representing phases of movement, structured rhythmic and melodically with counterpoints like a symphony. It has been claimed that parts actually form a coherent animation if the figures are shot frame by frame.[11] Although the structure follows a unique time-space continuum, it has narrative strategies.[12]

The Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius (c. 99 BCE – c. 55 BCE) wrote in his poem De rerum natura a few lines that come close to the basic principles of animation: "...when the first image perishes and a second is then produced in another position, the former seems to have altered its pose. Of course, this must be supposed to take place very swiftly: so great is their velocity, so great the store of particles in any single moment of sensation, to enable the supply to come up." This was in the context of dream images, rather than images produced by an actual or imagined technology.[13][14]

The medieval codex Sigenot (circa 1470) has sequential illuminations with relatively short intervals between different phases of action. Each page has a picture inside a frame above the text, with great consistency in size and position throughout the book (with a consistent difference in size for the recto and verso sides of each page).[15]

A page of drawings[16] by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) show anatomical studies with four different angles of the muscles of shoulder, arm and neck of a man. The four drawings can be read as a rotating movement.

Ancient Chinese records contain several mentions of devices, including one made by the inventor Ding Huan, said to "give an impression of movement" to a series of human or animal figures on them,[17] but these accounts are unclear and may only refer to the actual movement of the figures through space.[18]

Since before 1000 CE, the Chinese had a rotating lantern that had silhouettes projected on its thin paper sides that appeared to chase each other. This was called the "trotting horse lamp" [走馬燈] as it would typically depict horses and horse-riders. The cut-out silhouettes were attached inside the lantern to a shaft with a paper vane impeller on top, rotated by heated air rising from a lamp. Some versions added extra motion with jointed heads, feet or hands of figures triggered by a transversely connected iron wire.[19]

Volvelles have moving parts, but these and other paper materials that can be manipulated into motion are usually not regarded as animation.

Shadow play[]

Shadow play has much in common with animation: people watching moving figures on a screen as a popular form of entertainment, usually a story with dialogue, sounds and music. The figures could be very detailed and very articulated.

The earliest projection of images was most likely done in primitive shadowgraphy dating back to prehistory. It evolved into more refined forms of shadow puppetry, mostly with flat jointed cut-out figures which are held between a source of light and a translucent screen. The shapes of the puppets sometimes include translucent color or other types of detailing. The history of shadow puppetry is uncertain, but seems to have originated in Asia, possibly in the 1st millennium BCE. Clearer records seem to go back to around 900 CE. It later spread to the Ottoman empire and seems not to have reached Europe before the 17th century. It became popular in France at the end of the 18th century. François Dominique Séraphin started his elaborate shadow shows in 1771 and performed them until his death in 1800. His heirs continued until their theatre closed in 1870. Séraphin sometimes used clockwork mechanisms to automate the show.

Around the time cinematography was developed, several theaters in Montmartre showed elaborate, successful "Ombres Chinoises" shows. The famous Le Chat Noir produced 45 different shows between 1885 and 1896.

The Magic Lantern[]

Moving images were possibly projected with the magic lantern since its invention by Christiaan Huygens in 1659. His sketches for magic lantern slides have been dated to that year and are the oldest known document concerning the magic lantern.[20] One encircled sketch depicts Death raising his arm from his toes to his head, another shows him moving his right arm up and down from his elbow and yet another taking his skull off his neck and placing it back. Dotted lines indicate the intended movements.

Techniques to add motion to painted glass slides for the magic lantern were described since circa 1700. These usually involved parts (for instance, limbs) painted on one or more extra pieces of glass moved by hand or small mechanisms across a stationary slide which showed the rest of the picture.[21] Popular subjects for mechanical slides included the sails of a windmill turning, a procession of figures, a drinking man lowering and raising his glass to his mouth, a head with moving eyes, a nose growing very long, rats jumping in the mouth of a sleeping man. A more complex 19th century rackwork slide showed the then known eight planets and their satellites orbiting around the sun.[22] Two layers of painted waves on glass could create a convincing illusion of a calm sea turning into a stormy sea tossing some boats about by increasing the speed of the manipulation of the different parts.

In 1770 Edmé-Gilles Guyot detailed how to project a magic lantern image on smoke to create a transparent, shimmering image of a hovering ghost. This technique was used in the phantasmagoria shows that became popular in several parts of Europe between 1790 and the 1830s. Other techniques were developed to produce convincing ghost experiences. The lantern was handheld to move the projection across the screen (which was usually an almost invisible transparent screen behind which the lanternist operated hidden in the dark). A ghost could seem to approach the audience or grow larger by moving the lantern away from the screen, sometimes with the lantern on a trolley on rails. Multiple lanterns made ghosts move independently and were occasionally used for superimposition in the composition of complicated scenes.[23]

Dissolving views became a popular magic lantern show, especially in England in the 1830s and 1840s.[23] These typically had a landscape changing from a winter version to a spring or summer variation by slowly diminishing the light from one version while introducing the aligned projection of the other slide.[24] Another use showed the gradual change of, for instance, groves into cathedrals.[25]

Between the 1840s and 1870s several abstract magic lantern effects were developed. This included the chromatrope which projected dazzling colorful geometrical patterns by rotating two painted glass discs in opposite directions.[26]

Occasionally small shadow puppets had been used in phantasmagoria shows.[23] Magic lantern slides with jointed figures set in motion by levers, thin rods, or cams and worm wheels were also produced commercially and patented in 1891. A popular version of these "Fantoccini slides" had a somersaulting monkey with arms attached to mechanism that made it tumble with dangling feet. Fantoccini slides are named after the Italian word for puppets like marionettes or jumping jacks.[27]

Animation before film[]

Numerous devices that successfully displayed animated images were introduced well before the advent of the motion picture. These devices were used to entertain, amaze, and sometimes even frighten people. The majority of these devices didn't project their images, and could only be viewed by a one or a few persons at a time. They were considered optical toys rather than devices for a large scale entertainment industry like later animation.[citation needed] Many of these devices are still built by and for film students learning the basic principles of animation.

Prelude[]

An article in the Quarterly Journal of Science, Literature, and The Arts (1821)[28] raised interest in optical illusions of curved spokes in rotating wheels seen through vertical apertures. In 1824, Peter Mark Roget provided mathematical details about the appearing curvatures and added the observation that the spokes appeared motionless. Roget claimed that the illusion is due to the fact "that an impression made by a pencil of rays on the retina, if sufficiently vivid, will remain for a certain time after the cause has ceased."[29] This was later seen as the basis for the theory of "persistence of vision" as the principle of how we see film as motion rather than the successive stream of still images actually presented to the eye. This theory has been discarded as the (sole) principle of the effect since 1912, but remains in many film history explanations. However, Roget's experiments and explanation did inspire further research by Michael Faraday and by Joseph Plateau that eventually brought about the invention of animation.

Thaumatrope (1825)[]

In April 1825 the first thaumatrope was published by W. Phillips (in anonymous association with John Ayrton Paris) and became a popular toy.[30] The pictures on either side of a small cardboard disc seem to blend into one combined image when it is twirled quickly by the attached strings. This is often used as an illustration of what has often been called "persistence of vision", presumably referring to the effect in which the impression of a single image persists although in reality two different images are presented with interruptions. It is unclear how much of the effect relates to positive afterimages. Although a thaumatrope can also be used for two-phase animation, no examples are known to have been produced with this effect until long after the phénakisticope had established the principle of animation.

Phénakisticope (1833)[]

The phénakisticope (better known by the misspelling phenakistiscope or phenakistoscope) was the first animation device using rapid successive substitution of sequential pictures. The pictures are evenly spaced radially around a disc, with small rectangular apertures at the rim of the disc. The animation could be viewed through the slits of the spinning disc in front of a mirror. It was invented in November or December 1832 by the Belgian Joseph Plateau and almost simultaneously by the Austrian Simon von Stampfer. Plateau first published about his invention in January 1833. The publication included an illustration plate of a fantascope with 16 frames depicting a pirouetting dancer.

The phénakisticope was successful as a novelty toy and within a year many sets of stroboscopic discs were published across Europe, with almost as many different names for the device - including Fantascope (Plateau), The Stroboscope (Stampfer) and Phénakisticope (Parisian publisher Giroux & Cie).

Zoetrope (1833/1866)[]

In July 1833, Simon Stampfer described the possibility of using the stroboscope principle in a cylinder (as well as on looped strips) in a pamphlet accompanying the second edition of his version of the phénakisticope.[31] British mathematician William George Horner suggested a cylindrical variation of Plateau's phénakisticope in January 1834. Horner planned to publish this Dædaleum with optician King, Jr in Bristol but it "met with some impediment probably in the sketching of the figures".[32]

In 1865, William Ensign Lincoln invented the definitive zoetrope with easily replaceable strips of images. It also had an illustrated paper disc on the base, which was not always exploited on the commercially produced versions.[33] Lincoln licensed his invention to Milton Bradley and Co. who first advertised it on December 15, 1866.[34]

Flip book (kineograph) (1868)[]

John Barnes Linnett patented the first flip book in 1868 as the kineograph.[35][36] A flip book is a small book with relatively springy pages, each having one in a series of animation images located near its unbound edge. The user bends all of the pages back, normally with the thumb, then by a gradual motion of the hand allows them to spring free one at a time. As with the phenakistoscope, zoetrope and praxinoscope, the illusion of motion is created by the apparent sudden replacement of each image by the next in the series, but unlike those other inventions, no view-interrupting shutter or assembly of mirrors is required and no viewing device other than the user's hand is absolutely necessary. Early film animators cited flip books as their inspiration more often than the earlier devices, which did not reach as wide an audience.[37]

The older devices by their nature severely limit the number of images that can be included in a sequence without making the device very large or the images impractically small. The book format still imposes a physical limit, but many dozens of images of ample size can easily be accommodated. Inventors stretched even that limit with the mutoscope, patented in 1894 and sometimes still found in amusement arcades. It consists of a large circularly-bound flip book in a housing, with a viewing lens and a crank handle that drives a mechanism that slowly rotates the assembly of images past a catch, sized to match the running time of an entire reel of film.

Praxinoscope (1877)[]

French inventor Charles-Émile Reynaud developed the praxinoscope in 1876 and patented it in 1877.[38] It is similar to the zoetrope but instead of the slits in the cylinder it has twelve rectangular mirrors placed evenly around the center of the cylinder. Each mirror reflects another image of the picture strip placed opposite on the inner wall of the cylinder. When rotating the praxinoscope shows the sequential images one by one, resulting in fluid animation. The praxinoscope allowed a much clearer view of the moving image compared to the zoetrope, since the zoetrope's images were actually mostly obscured by the spaces in between its slits. In 1879, Reynaud registered a modification to the praxinoscope patent to include the Praxinoscope Théâtre, which utilized the Pepper's ghost effect to present the animated figures in an exchangeable background. Later improvements included the "Praxinoscope à projection" (marketed since 1882) which used a double magic lantern to project the animated figures over a still projection of a background.[39]

Zoopraxiscope (1879)[]

Eadweard Muybridge had circa 70 of his famous chronophotographic sequences painted on glass discs for the zoopraxiscope projector that he used in his popular lectures between 1880 and 1895. In the 1880s the images were painted onto the glass in dark contours. Later discs made between 1892 and 1894 had outlines drawn by Erwin F. Faber that were photographically printed on the disc and then coloured by hand, but these were probably never used in the lectures. The painted figures were largely transposed from the photographs, but many fanciful combinations were made and sometimes imaginary elements were added.[40][41]

1888–1908: Earliest animations on film[]

Théâtre Optique[]

Charles-Émile Reynaud further developed his projection praxinoscope into the Théâtre Optique with transparent hand-painted colorful pictures in a long perforated strip wound between two spools, patented in December 1888. From 28 October 1892 to March 1900 Reynaud gave over 12,800 shows to a total of over 500,000 visitors at the Musée Grévin in Paris. His Pantomimes Lumineuses series of animated films each contained 300 to 700 frames manipulated back and forth to last 10 to 15 minutes per film. A background scene was projected separately. Piano music, song and some dialogue were performed live, while some sound effects were synchronized with an electromagnet. The first program included three cartoons: Pauvre Pierrot (created in 1892), Un bon bock (created in 1892, now lost), and Le Clown et ses chiens (created in 1892, now lost). Later on the titles Autour d'une cabine (created in 1894) and A rêve au coin du feu would be part of the performances.

Standard picture film[]

Despite the success of Reynaud's films, it took some time before animation was adapted in the film industry that came about after the introduction of Lumiere's Cinematograph in 1895. Georges Méliès' early fantasy and trick films (released between 1896 and 1913) occasionally came close to including animation with stop trick effects, painted props or painted creatures that were moved in front of painted backgrounds (mostly using wires), and film colorization by hand. Méliès also popularized the stop trick, with a single change made to the scene in between shots, that had already been used in Edison's The Execution of Mary Stuart in 1895 and probably led to the development of stop-motion animation some years later.[42] It seems to have lasted until 1906 before proper animated films' appearance in cinemas. The dating of earlier films with animation is contested, while other films that may have used stop motion or other animation techniques are lost and can't be checked.

Printed animation film[]

In 1897 German toy manufacturer Gebrüder Bing had a first prototype of their kinematograph.[43] In November 1898 they presented this toy film projector, possibly the first of its kind, at a toy festival in Leipzig. Soon other toy manufacturers, including Ernst Plank and Georges Carette, sold similar devices. Around the same time the French company Lapierre marketed a similar projector. The toy cinematographs were adapted toy magic lanterns with one or two small spools that used standard "Edison perforation" 35mm film. These projectors were intended for the same type of "home entertainment" toy market that most of these manufacturers already provided with praxinoscopes and toy magic lanterns. Apart from relatively expensive live-action films, the manufacturers produced many cheaper films by printing lithographed drawings. These animations were probably made in black-and-white from around 1898 or 1899, but at the latest by 1902 they were made in color. The pictures were often traced from live-action films (much like the later rotoscoping technique). These very short films depicted a simple repetitive action and were created to be projected as a loop - playing endlessly with the film ends put together. The lithograph process and the loop format follow the tradition that was set by the zoetrope and praxinoscope.[44][45]

Katsudō Shashin, from an unknown creator, was discovered in 2005 and is speculated to be the oldest work of animation in Japan, with Natsuki Matsumoto,[Note 1][46] an expert in iconography at the Osaka University of Arts[47] and animation historian Nobuyuki Tsugata[Note 2] determining the film was most likely made between 1907 and 1911.[48] The film consists of a series of cartoon images on fifty frames of a celluloid strip and lasts three seconds at sixteen frames per second.[49] It depicts a young boy in a sailor suit who writes the kanji characters "活動写真" (katsudō shashin, or "moving picture"), then turns towards the viewer, removes his hat, and offers a salute.[49] Evidence suggests it was mass-produced to be sold to wealthy owners of home projectors.[50] To Matsumoto, the relatively poor quality and low-tech printing technique indicate it was likely from a smaller film company.[51]

J. Stuart Blackton[]

J. Stuart Blackton was a British-American filmmaker, co-founder of the Vitagraph Studios and one of the first to use animation in his films. His The Enchanted Drawing (1900) can be regarded as the first theatrical film recorded on standard picture film that included animated elements, although this concerns just a few frames of changes in drawings. It shows Blackton doing "lightning sketches" of a face, cigars, a bottle of wine and a glass. The face changes expression when Blackton pours wine into the face's mouth and when Blackton takes his cigar. The technique used in this film was basically the stop trick: the single change to the scenes was the replacement of a drawing by a similar drawing with a different facial expression. In some scenes, a drawn bottle and glass were replaced by real objects. Blackton had possibly used the same technique in a lost 1896 lightning sketch film.[42]

Blackton's 1906 film Humorous Phases of Funny Faces is often regarded as the oldest known drawn animation on standard film. It features a sequence made with blackboard drawings that are changed between frames to show two faces changing expressions and some billowing cigar smoke, as well as two sequences that feature cutout animation with a similar look for more fluid motion.

Blackton's use of stop motion in The Haunted Hotel (1907) was very influential.

Émile Cohl[]

The French artist Émile Cohl created the first animated film using what came to be known as traditional animation methods: the 1908 Fantasmagorie.[52] The film largely consisted of a stick figure moving about and encountering all manner of morphing objects, such as a wine bottle that transforms into a flower. There were also sections of live action where the animator's hands would enter the scene. The film was created by drawing each frame on paper and then shooting each frame onto negative film, which gave the picture a blackboard look. Cohl later went to Fort Lee, New Jersey near New York City in 1912, where he worked for French studio Éclair and spread its animation technique to the US.

1910s: From original artists to "assembly-line" production studios[]

Winsor McCay[]

Starting with a short 1911 film of his most popular character Little Nemo, successful newspaper cartoonist Winsor McCay gave much more detail to his hand-drawn animations than any animation previously seen in cinemas. His 1914 film Gertie the Dinosaur featured an early example of character development in drawn animation.[53] It was also the first film to combine live-action footage with animation. Originally, McCay used the film in his vaudeville act: he would stand next to the screen and speak to Gertie who would respond with a series of gestures. At the end of the film McCay would walk behind the projection screen, seamlessly being replaced with a prerecorded image of himself entering the screen, getting on the cartoon dinosaur's back and riding out of frame.[54][55] McCay personally hand-drew almost every one of the thousands of drawings for his films.[56] Other noteworthy titles by McCay are How a Mosquito Operates (1912) and The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918).

Cartoon Film Company – Buxton and Dyer[]

Between 1915 and 1916 Dudley Buxton, and Anson Dyer produced a series of 26 topical cartoons, during WWI, utilising mainly cutout animation, released as the John Brown's animated sketchbook,[57] The episodes included the shelling of Scarborough by German battleships,[58] and The Sinking of the Lusitania, No.4 (June 1915)[59]

Barré Studio[]

During the 1910s larger-scale animation studios were becoming the industrial norm and artists such as McCay faded from the public eye.[56]

Around 1913 Raoul Barré developed the peg system that made it easier to align drawings by perforating two holes below each drawing and placing them on two fixed pins. He also used a "slash and tear" technique to not have to draw the complete background or other motionless parts for every frame. The parts where something needed to be changed for the next frame were carefully cut away from the drawing and filled in with the required change on the sheet below.[60] After Barré had started his career in animation at Edison Studios, he founded one of the first film studios dedicated to animation in 1914 (initially together with Bill Nolan). Barré Studio had success with the production of the adaptation of the popular comic strip Mutt and Jeff (1916–1926). The studio employed several animators who would have notable careers in animation, including Frank Moser, Gregory La Cava, Vernon Stallings, Tom Norton and Pat Sullivan.

Bray Productions[]

In 1914, John Bray opened John Bray Studios, which revolutionized the way animation was created.[61] Earl Hurd, one of Bray's employees, patented the cel technique.[62] This involved animating moving objects on transparent celluloid sheets.[63] Animators photographed the sheets over a stationary background image to generate the sequence of images. This, as well as Bray's innovative use of the assembly-line method, allowed John Bray Studios to create Colonel Heeza Liar, the first animated series.[64][65] Many aspiring cartoonists started their careers at Bray, including Paul Terry (later of Heckle and Jeckle fame), Max Fleischer (later of Betty Boop and Popeye fame), and Walter Lantz (later of Woody Woodpecker fame). The cartoon studio operated from circa 1914 until 1928. Some of the first cartoon stars from the Bray studios were Farmer Alfalfa (by Paul Terry) and Bobby Bumps (by Earl Hurd).

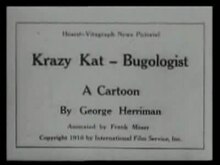

Hearst's International Film Service[]

Newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst founded International Film Service in 1916. Hearst lured away most of Barré Studio's animators, with Gregory La Cava becoming the head of the studio. They produced adaptations of many comic strips from Heart's newspapers in a rather limited fashion, giving just a little motion to the characters while mainly using the dialog balloons to deliver the story. The most notable series is Krazy Kat, probably the first of many anthropomorphic cartoon cat characters and other funny animals. Before the studio stopped in 1918, it had employed some new talents, including Vernon Stallings, Ben Sharpsteen, Jack King, John Foster, Grim Natwick, Burt Gillett and Isadore Klein.

Fleischer Studios[]

In 1915, Max Fleischer applied for a patent (granted in 1917)[66] for a technique which became known as rotoscoping: the process of using live-action film recordings as a reference point to more easily create realistic animated movements. The technique was often used in the Out of the Inkwell series (1918–1929) for John Bray Productions (and others). The series resulted from experimental rotoscoped images of Dave Fleischer performing as a clown, evolving into a character who became known as Koko the Clown.

Felix the cat[]

In 1919, Otto Messmer of Pat Sullivan Studios created Felix the Cat. Pat Sullivan, the studio head took all of the credit for Felix, a common practice in the early days of studio animation.[67] Felix the Cat was distributed by Paramount Studios and attracted a large audience,[68] eventually becoming one of the most recognized cartoon characters in film history. Felix was the first cartoon to be merchandised.[citation needed]

Quirino Cristiani: the first animated features[]

The first known animated feature film was El Apóstol by Quirino Cristiani, released on 9 November 1917 in Argentina. This successful 70-minute satire utilized a cardboard cutout technique, reportedly with 58,000 frames at 14 frames per second. Cristiani's next feature Sin dejar rastros was released in 1918, but it received no press coverage and poor public attendance before it was confiscated by the police for diplomatic reasons.[69] None of Cristiani's feature films survived.[70][71][72]

1920s: Absolute film, transition to synchronized sound and the rise of Disney[]

Absolute film[]

In the early 1920s, the absolute film movement with artists such as Walter Ruttmann, Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling and Oskar Fischinger made short abstract animations which proved influential. Although some later abstract animation works by, for instance, Len Lye and Norman McLaren would be widely appreciated, the genre largely remained a relatively obscure avant-garde art form, while direct influences or similar ideas would occasionally pop up in mainstream animation (for instance in Disney's Toccata and Fugue in D Minor in Fantasia (1940) – on which Fischinger originally collaborated until his work was scrapped, and partly inspired by the works of Lye – and in The Dot and the Line (1965) by Chuck Jones).

Early synchronized sound: Song Car-Tunes and Aesop's Sound Fables[]

From May 1924 to September 1926, Dave and Max Fleischer's Inkwell Studios produced 19 sound cartoons, part of the Song Car-Tunes series, using the Phonofilm "sound-on-film" process. The series also introduced the "bouncing ball" above lyrics to guide audiences to sing along to the music. My Old Kentucky Home from June 1926 was probably the first film to feature a bit of synchronized animated dialogue, with an early version of Bimbo mouthing the words "Follow the ball, and join in, everybody". The Bimbo character was further developed in Fleischer's Talkartoons (1929–1932).

Paul Terry's Dinner Time, from his Aesop's Fables (1921–1936) series, premiered on 1 September 1928 with a synchronized soundtrack with dialogue. Terry was urged to add the novelty against his wishes by the new studio owner Van Beuren. Although the series and its main character Farmer Al Falfa had been popular, audiences were not impressed by this first episode with sound.

Lotte Reiniger[]

The earliest surviving animated feature film is the 1926 silhouette-animated Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed (Adventures of Prince Achmed), which used colour-tinted film.[73] It was directed by German Lotte Reiniger and her husband Carl Koch. Walter Ruttmann created visual background effects. French/Hungarian collaborator Berthold Bartosch and/or Reiniger created depth of field by putting scenographic elements and figures on several levels of glass plates with illumination from below and the camera vertically above. Later on a similar technique became the basis of the multiplane camera.

Early Disney: Laugh-O-Grams, Alice, Oswald and Mickey[]

Between 1920 and 1922, cartoonists Walt Disney, Ub Iwerks and Fred Harman worked at the Slide Company (soon renamed as Kansas City Film Ad Company), which produced cutout animation commercials. Disney and Ub studied Muybridge's chronophotography and the one book on animation in the local library, and Disney experimented with drawn animation techniques in his parents' garage. They were able to bring some innovations to the company, but their employer did not want to forsake the trusted cutout technique. Disney's home experiments led to a series that satirized current local topics, which he managed to sell to the owner of the three local Newman Theatres as weekly Newman Laugh-O-Grams in 1921. While striking the deal, the 19-year old Disney forgot to include a profit margin, but he was happy that someone paid for his "experiment" and gained local renown from the screenings. Disney also created his first recurring character, Professor Whosis, appearing in humorous public announcements for Newman.

Disney and Harman started their own Kaycee Studio on the side, experimenting with films played backwards, but their efforts to make money with commercials and newsreel footage were not very fruitful and Harman left in 1922. Through a newspaper ad, Disney "hired" Rudolph Ising in exchange for teaching him the ins and outs of animation. Inspired by Terry's Aesop's Fables, Disney started a series of circa seven-minute modernized fairy tale cartoons, and a new series of satirical actualities called Lafflets, with Ising's help. After two fairy-tale cartoons, Disney quit his job at Film Ad and started Laugh-O-Gram Films, Inc. with the help of investors. Iwerks, Fred's brother Hugh Harman and Carman Maxwell were among the animators who would produce five more Laugh-O-Gram fairy tale cartoons and the sponsored Tommy Tucker's Tooth in 1922.[74] The series failed to make money and in 1923 the studio tried something else with the live-action "Song-O-Reel" Martha[75] and Alice's Wonderland. The 12-minute film featured a live-action girl (Virginia Davis) interacting with numerous cartoon characters, including the Felix-inspired Julius the Cat (who had already appeared in the Laugh-O-Gram fairy tales, without a name). Before Disney was able to sell the picture, his studio went bankrupt.

Disney moved to Hollywood and managed to close a deal with New York film distributor Margaret J. Winkler, who had just lost the rights to Felix the Cat and Out of the Inkwell. To make the Alice Comedies series (1923–1927), Iwwerks also moved to Hollywood, later followed by Ising, Harman, Maxwell and Film Ad colleague Friz Freleng. The series was successful enough to last 57 episodes, but Disney eventually preferred to create a new fully animated series.

Oswald the Lucky Rabbit followed in 1927 and became a hit, but after failed negotiations for continuation in 1928, Charles Mintz took direct control of production and Disney lost his character and most of his staff to Mintz.

Disney and Iwerks developed Mickey Mouse in 1928 to replace Oswald. A first film entitled Plane Crazy failed to impress a test audience and did not raise sufficient interest of potential distributors. After some live-action movies with synchronized sound had become successful, Disney put the new Mickey Mouse cartoon The Gallopin' Gaucho on hold to start work on a special sound production which would launch the series more convincingly. Much of the action in the resulting Steamboat Willie (November 1928) involves the making of sounds, for instance with Mickey making music using livestock aboard the boat. The film became a huge success and Mickey Mouse would soon become the most popular cartoon character in history.

Bosko[]

Bosko was created in 1927 by Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising, specifically with talkies in mind. They were still working for Disney at the time, but they left in 1928 to work on the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons at Universal for about a year, and then produced Bosko, the Talk-Ink Kid pilot in May 1929 to shop for a distributor. They signed with Leon Schlesinger productions and started the Looney Tunes series for Warner Bros. in 1930. Bosko was the star of 39 Warner Bros. cartoons before Harman and Ising took Bosko to MGM after leaving Warner Bros.. After two MGM cartoons, the character received a dramatic make-over that was much less appreciated by audiences. Bosko's career ended in 1938.

1930s: Color, depth, cartoon superstars and Snow White[]

The lithographed films for home use that were available in Europe in the first decades of the twentieth century were multi-coloured, but the technique does not seem to have been applied for theatrically released animated films. While the original prints of The Adventures of Prince Achmed featured film tinting, most theatrically released animated films before 1930 were plain black and white. Effective color processes were a welcome innovation in Hollywood and seemed especially suitable for cartoons.

Two-strip color[]

A cartoon segment in the feature film King of Jazz (April 1930), made by Walter Lantz and Bill Nolan, was the first animation presented in two-strip Technicolor.

Fiddlesticks, released together with King of Jazz, was the first Flip the Frog film and the first project Ub Iwerks worked on after he had left Disney to set up his own studio. In England, the cartoon was released in Harris Color,[76] a two-color process, probably as the first theatrically released standalone animated cartoon to boast both sound and color.

Disney's Silly Symphonies in Technicolor[]

When the Silly Symphonies series, started in 1929, was less popular than Disney had hoped, he turned to a new technical innovation to improve the impact of the series. In 1932 he worked with the Technicolor company to create the first full-colour animation Flowers and Trees, debuting the three-strip technique (the first use in live-action movies came circa two years later). The cartoon was successful and won an Academy Award for Short Subjects, Cartoons.[77] Disney temporarily had an exclusive deal for the use of Technicolor's full color technique in animated films. He even waited a while before he produced the ongoing Mickey Mouse series in color, so the Silly Symphonies would have their special appeal for audiences. After the exclusive deal lapsed in September 1935, full color animation soon became the industry standard.

Silly Symphonies inspired many cartoon series that boasted various other color systems until Technicolor wasn't exclusive to Disney anymore, including Ub Iwerks' ComiColor Cartoons (1933–1936), Van Beuren Studios' Rainbow Parade (1934–1936), Fleischer's Color Classics (1934–1941), Charles Mintz's Color Rhapsody (1936–1949), MGM's Happy Harmonies (1934–1938) George Pal's Puppetoons (1932–1948), and Walter Lantz's Swing Symphony (1941–1945).

Multiplane cameras and the Stereoptical process[]

To create an impression of depth, several techniques were developed. The most common technique was to have characters move between several background and/or foreground layers that could be moved independently, corresponding to the laws of perspective (e.g. the further away from the camera, the slower the speed).

Lotte Reiniger had already designed a type of multiplane camera for Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed[78] and her collaborator Berthold Bartosch used a similar setup for his intricately detailed 25-minute film L'Idée (1932).

In 1933, Ub Iwerks developed a multiplane camera and used it for a number of Willie Whopper (1933–1934) and ComiColor Cartoons episodes.

The Fleischers developed the very different "Stereoptical process" in 1933[79] for their Color Classics. It was used in the first episode Betty Boop in Poor Cinderella (1934) and most of the following episodes. The process involved three-dimensional sets built and sculpted on a large turntable. The cels were placed within the movable set, so that the animated characters would appear to move in front and behind of the 3D elements within the scene when the turntable was made to rotate.

Disney-employee William Garity developed a multiplane camera that could have up to seven layers of artwork. It was tested in the Academy Award-winning Silly Symphony The Old Mill (1937) and used prominently in Snow White and later features.

New colourful cartoon superstars[]

After the additions of sound and colour were a huge success for Disney, other studios followed. By the end of the decade, almost all the theatrical cartoons were produced in full colour.

Initially, music and songs were the focus of many series, as indicated by series titles as Song Car-Tunes, Silly Symphonies, Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes, but it was the recognizable characters that really stuck with audiences. Mickey Mouse had been the first cartoon superstar who surpassed Felix the Cat's popularity, but soon dozens more cartoon superstars followed, many remaining popular for decades.

Warner Bros. had a vast music library that could be popularized through cartoons based on the available tunes. While Disney needed to create the music for every cartoon, the readily available sheet music and songs at Warner Bros. provided inspiration for many cartoons. Leon Schlesinger sold Warner Bros. a second series called Merrie Melodies, which until 1939 contractually needed to contain at least one refrain from the music catalog. Unlike Looney Tunes with Bosko, Merrie Melodies featured only a few recurring characters like Foxy, Piggy and Goopy Geer before Harman and Ising left in 1933. Bosko was replaced with Buddy for the Looney Tunes series, but lasted only two years, while Merrie Melodies initially continued without recurring characters. Eventually, the two series became indistinguishable and produced many new characters that became popular. Animator/director Bob Clampett designed Porky Pig (1935) and Daffy Duck (1937) and was responsible for much of the energetic animation and irreverent humour associated with the series. The 1930s also saw early anonymous incarnations of characters who would later become the superstars Elmer Fudd (1937/1940), Bugs Bunny (1938/1940) and Sylvester the Cat (1939/1945). Since 1937, Mel Blanc would perform most of the characters' voices.

Disney introduced new characters to the Mickey Mouse universe who would become very popular, to star together with Mickey and Minnie Mouse (1928): Pluto (1930), Goofy (1932), and a character who would soon become the new favourite: Donald Duck (1934). Disney had realized that the success of animated films depended upon telling emotionally gripping stories; he developed a "story department" where storyboard artists separate from the animators would focus on story development alone, which proved its worth when the Disney studio released in 1933 the first animated short to feature well-developed characters, Three Little Pigs.[80][81][82] Disney would expand his studio and start more and more production activities, including comics, merchandise and theme parks. Most projects were based on the characters developed for theatrical short films.

Fleischer Studios introduced an unnamed dog character as Bimbo's girlfriend in Dizzy Dishes (1930), who evolved into the human female Betty Boop (1930–1939) and became Fleischer's best-known creation. In the 1930s they also added Hunky and Spunky (1938) and the popular animated adaptation of Popeye (1933) to their repertoire.

Hays code and Betty Boop[]

Hays' Motion Picture Production Code for moral guidelines was applied in 1930 and rigidly enforced between 1934 and 1968. It had a big impact on filmmakers who liked to create relatively saucy material. As an infamous example, Betty Boop suffered greatly when she had to be changed from a carefree flapper with an innocent sex appeal into a more wholesome and much tamer character in fuller dress. Her boyfriend Bimbo's disappearance was probably also the result of the codes disapproval of mixed-species relationships.

Snow White and the breakthrough of the animated feature[]

At least eight animated feature films were released before Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, while at least another two earlier animated feature projects remained unfinished. Most of these films (of which only four survive) were made using cutout, silhouette or stop-motion techniques. Among the lost animated features were three features by Quirino Cristiani, who had premiered his third feature Peludópolis on 18 September 1931 in Buenos Aires[83] with a Vitaphone sound-on-disc synchronized soundtrack. It was received quite positively by critics, but did not become a hit and was an economic fiasco for the filmmaker. Cristiani soon realized that he could no longer make a career with animation in Argentina.[69] Only Academy Award Review of Walt Disney Cartoons—also by Disney—was totally hand-drawn. It was released seven months prior to Snow White to promote the upcoming release of Snow White.[citation needed]. Many do not consider this a genuine feature film, because it is a package film and lasts only 41 minutes. It does meet the official definitions of a feature film by the British Film Institute, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the American Film Institute, which require that the film has to be over 40 minutes long.

When it became known that Disney was working on a feature-length animation, critics regularly referred to the project as "Disney's folly", not believing that audiences could stand the expected bright colors and jokes for such a long time. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs premiered on 21 December 1937 and became a worldwide success. The film continued Disney's tradition to appropriate old fairy tales and other stories (started with the Laugh-O-Grams in 1921), as would most of the Disney features that followed.

The Fleischer studios followed Disney's example with Gulliver's Travels in 1939, which was a minor success at the box office.

Early TV animation[]

In April 1938, when about 50 television sets were connected, NBC aired the eight-minute low-budget cartoon Willie the Worm. It was especially made for this broadcast by former Disney employee Chad Grothkopf, mainly with cutouts and a bit of cel animation.

About a year later, on 3 May 1939, Disney's Donald's Cousin Gus was premiered on NBC's experimental W2XBS channel a few weeks before it was released in movie theatres. The cartoon was part of the first full-evening programme.[84]

1940s[]

Wartime propaganda[]

Several governments had already used animation in public information films, like those by the GPO Film Unit in the U.K. and Japanese educational films. During World War II, animation became a common medium for propaganda. The US had their best studios working for the war effort.

To instruct service personnel about all kinds of military subjects and to boost morale, Warner Bros. was contracted for several shorts and the special animated series Private Snafu. The character was created by the famous movie director Frank Capra, Dr. Seuss was involved in screenwriting and the series was directed by Chuck Jones. Disney also produced several instructive shorts and even personally financed the feature-length Victory Through Air Power (1943) that promoted the idea of long-range bombing.

Many popular characters promoted war bonds, like Bugs Bunny in Any Bonds Today?, Disney's little pigs in The Thrifty Pig and a whole bunch of Disney characters in All Together. Daffy Duck asked for scrap metal for the war effort in Scrap Happy Daffy. Minnie Mouse and Pluto invited civilians to collect their cooking grease so it could be used for making explosives in Out of the Frying Pan Into the Firing Line. There were several more political propaganda short films, like Warner Bros.' Fifth Column Mouse, Disney's Chicken Little and the more serious Education for Death and Reason and Emotion (nominated for an Academy Award).

Such wartime films were much appreciated. Bugs Bunny became something of a national icon and Disney's propaganda short Der Fuehrer's Face (starring Donald Duck) won the company its tenth Academy Award for cartoon short subjects.

Japan's first feature anime 桃太郎 海の神兵 (Momotaro: Sacred Sailors) was made in 1944, ordered by the Ministry of the Navy of Japan. It was designed for children and, partly inspired by Fantasia, was meant to inspire dreams and hope for peace. The main characters are an anthropomorphic monkey, dog, bear and pheasant who become parachute troopers (except the pheasant who becomes a pilot) tasked with invading Celebes. An epilogue hints at America being the target for the next generation.

Feature animation in the 1940s[]

High ambitions, setbacks and cutbacks in US feature animation[]

Disney's next features (Pinocchio and the very ambitious concert-film Fantasia, both released in 1940) and Fleischer Studios' second animated feature Mr. Bug Goes to Town (1941/1942) were all received favorably by critics but failed at the box office during their initial theatrical runs. The primary cause was that World War II had cut off most foreign markets. These setbacks discouraged most companies who had plans for animated features.

Disney cut back on the costs for the next features and first released The Reluctant Dragon, mostly consisting of a live-action tour of the new studio in Burbank, partly in black and white, with four short cartoons. It was a mild success at the worldwide box office. It was followed a few months later by Dumbo (1941), only 64 minutes long and animated in a simpler economic style. This helped securing a profit at the box office, and critics and audiences reacted positively. Disney's next feature Bambi (1942) returned to a larger budget and more lavish style, but the more dramatic story, darker mood and lack of fantasy elements was not well-received during its initial run and lost money at the box office.

Although all the other eight Disney features of the 1940s were package films, and/or combinations with live-action (for instance Saludos Amigos (1943) and The Three Caballeros (1944)), Disney kept faith in animated feature animation. For decades, Disney was the only American studio to release animated theatrical feature films regularly, though some other American studios did manage to release more than a handful before the beginning of the 1990s.

Non-US animation forces[]

American cel-animated films dominated the worldwide production and consumption of theatrical animated releases since the 1920s. Especially Disney's work proved to be very popular and most influential around the world. Studios from other countries could hardly compete with the American productions. Relatively many animation producers outside the US chose to work with other techniques than "traditional" or cel animation, such as puppet animation or cut-out animation. However, several countries (most notably Russia, China and Japan) developed their own relatively large "traditional" animation industries. Russia's Soyuzmultfilm animation studio, founded in 1936, employed up to 700 skilled workers and, during the Soviet period, produced 20 films per year on average. Some titles noticed outside their respective domestic markets include 铁扇公主 (Princess Iron Fan)[85] (China 1941, influential in Japan), Конёк-Горбуно́к (The Humpbacked Horse) (Russia 1947, winner special jury award in Cannes in 1950), I Fratelli Dinamite (The Dynamite Brothers) (Italy 1949) and La Rosa di Bagdad (The Rose of Baghdad) (Italy 1949, the 1952 English dub starred Julie Andrews).

Successful theatrical short cartoons of the 1940s[]

During the "Golden Age of American animation", new studios competed with the studios that survived the sound and colour innovation battles of the previous decades. Funny animals were still the norm and music was still a relevant element, but often lost its main stage appeal to Disney's melodramatic storytelling or the wild humour in Looney Tunes and other cartoons.

Disney continued their cartoon successes, adding Daisy Duck (1940) and Chip 'n' Dale (1943/1947) to the Mickey Mouse universe, while Warner Bros. developed new characters to join their popular Merrie Melodies/Looney Tunes cast, including Tweety (1941/1942), Henery Hawk (1942), Yosemite Sam (1944/1945), Foghorn Leghorn (1946), Barnyard Dawg (1946), Marvin the Martian (1948), and Wile E. Coyote and Road Runner (1949).

Other new popular characters and series were Terrytoons' Mighty Mouse (1942–1961) and Heckle and Jeckle (1946), and Screen Gems' The Fox and the Crow (1941–1948).

Fleischer/Famous Studios[]

Fleischer launched its spectacular Superman adaptation in 1941. The success came too late to save the studio from its financial problems and in 1942 Paramount Pictures took over the studio from the resigning Fleischer Brothers. The renamed Famous Studios continued the Popeye and Superman series, developed popular adaptations of Little Lulu (1943–1948, licensed by Gold Key Comics), Casper the friendly ghost (1945) and created new series, such as Little Audrey (1947) and Baby Huey (1950).

Walter Lantz Productions[]

Walter Lantz had started his animation career at Hearst's studio at the age of 16. He had also worked for the Bray Studios and Universal Pictures, where he had gained control over the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons in 1929 (reportedly by winning the character and control of the studio in a poker bet with Universal president Carl Laemmle). In 1935, the Universal studio was turned into the independent Walter Lantz Productions, but remained on the Universal lot and continued to produce cartoons for Universal to distribute. When Oswald's popularity dwindled and the character was eventually retired in 1938, Lantz's productions went without successful characters until he developed Andy Panda in 1939. The anthropomorphic panda starred in over two-dozen cartoons until 1949, but he was soon overshadowed by the iconic Woody Woodpecker, who debuted in the Andy Panda cartoon Knock Knock in 1940. Other popular Lantz characters include Wally Walrus (1944), Buzz Buzzard (1948), Chilly Willy (1953), Hickory, Dickory, and Doc (1959).

MGM[]

After distributing Ub Iwerks' Flip the Frog and Willie Whopper cartoons and Happy Harmonies by Harman and Ising, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer founded its own cartoon studio in 1937. The studio had much success with Barney Bear (1939–1954), Hanna and Joseph Barbera's Tom and Jerry (1940) and Spike and Tyke (1942).

In 1941, Tex Avery left Warner Bros. for MGM and would there create Droopy (1943), Screwy Squirrel (1944) and George and Junior (1944).

UPA[]

While Disney and most of the other studios sought a sense of depth and realism in animation, UPA animators (including former Disney employee John Hubley) had a different artistic vision. They developed a much sparser and more stylized type of animation, inspired by Russian examples. The studio was formed in 1943 and initially worked on government contracts. A few years later they signed a contract with Columbia Pictures, took over The Fox and the Crow from Screen Gems and earned Oscar nominations for their first two theatrical shorts in 1948 and 1949. While the field of animation was dominated by anthropomorphic animals when the studio was allowed to create a new character, they came up with the near-sighted old man. Mr. Magoo (1949) became a hit and would be featured in many short films. Between 1949 and 1959 UPA received 15 Oscar nominations, winning their first Academy Award with the Dr. Seuss adaptation Gerald McBoing-Boing (1950), followed by two more for When Magoo Flew (1954) and Magoo's Puddle Jumper (1956). The distinctive style was influential and even affected the big studios, including Warner Bros. and Disney. Apart from an effective freedom in artistic expression, UPA had proved that sparser animation could be appreciated as much as (or even more than) the expensive lavish styles.

TV animation in the 1940s[]

The back catalog of animated cartoons of many studios, originally produced for a short theatrical run, proved very valuable for television broadcasting. Movies for Small Fry (1947), presented by "big brother" Bob Emery on Tuesday evenings on the New York WABD-TV channel, was one of the first TV series for children and featured many classic Van Beuren Studios cartoons. It was continued on the DuMont Television Network as the daily show Small Fry Club (1948–1951) with a live audience in a studio setting.

Many classical series from Walter Lantz, Warner Bros., Terrytoons, MGM and Disney similarly found a new life in TV shows for children, with many reruns, for decades. Instead of studio settings and live-action presentation, some shows would feature new animation to present or string together the older cartoons.

The earliest American animated series specifically produced for TV came about in 1949, with Adventures of Pow Wow (43 five-minute episodes broadcast on Sunday mornings from January to November) and Jim and Judy in Teleland (52 episodes, later also sold to Venuzuela and Japan).

1950s: Shift from classic theatrical cartoons to limited animation in TV series for children[]

Most theatrical cartoons had been produced for non-specific audiences. Dynamic action and gags with funny animals in clear drawing styles and bright colours were naturally appealing to young children, but the cartoons regularly contained violence and sexual innuendo and were often screened together with news reels and feature films that were not for children. On US television, cartoons were mainly programmed for children in convenient time slots on weekend mornings, weekday afternoons or early evenings.

The scheduling constraints of the 1950s American TV animation process, notably issues of resource management (higher quantity needed to be made in less time for a lower budget compared to theatrical animation), led to the development of various techniques known now as limited animation. The sparser type of animation that originally had been an artistic choice of style for UPA, was embraced as a means to cut back production time and costs. Full-frame animation ("on ones") became rare in the United States outside its use for increasingly less theatrical productions. Chuck Jones coined the term "illustrated radio" to refer to the shoddy style of most television cartoons that depended more on their soundtracks than visuals.[86] Some producers also found that limited animation looked better on the small (black-and-white) TV screens of the time.[87]

Animated TV series of the 1950s[]

Jay Ward produced the popular Crusader Rabbit (tested in 1948, original broadcasts in 1949–1952 and 1957–1959), with successful use of a limited-animation style.

At the end of the 1950s, several studios dedicated to TV animation production started competing. While the focus for competition in theatrical animation had been on quality and innovation, it now shifted to delivering animation fast and cheap. Critics noted how the quality of many shows was often poor in comparison to the classic cartoons, with rushed animation and run-of-the-mill stories. Network executives were satisfied as long as there were enough viewers,[88] and the huge amounts of young viewers were not bothered with the lack of quality that the critics perceived. Watching Saturday-morning cartoon programming, up to four hours long, became a favorite pastime of most American children since the mid-1960s and was a mainstay for decades.

Disney had entered into TV production relatively early, but refrained from creating newly animated series for decades. Instead, Disney had their own anthology series on the air since 1954 in primetime three-hour slots, starting with the Walt Disney's Disneyland series (1954–1958), clearly promoting the Disneyland theme park that opened in 1955. Walt Disney personally hosted the series that apart from older cartoons featured segments with, for instance, looks behind the scenes on film-making processes or new live-action adventures.

William Hanna and Joseph Barbera (the creators of Tom and Jerry) continued as Hanna-Barbera after Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer closed their animation studio in 1957, when MGM considered their back catalog sufficient for further sales.[89] While Hanna-Barbera only made one theatrically released series with Loopy de Loop (1959–1965), they proved to be the most prolific and successful producers of animated television series for several decades. Starting with The Ruff and Reddy Show (1957–1960), they continued with successful series like The Huckleberry Hound Show (1958, the first half-hour television program to feature only animation)[90] and The Quick Draw McGraw Show (1959–1961).

Other notable programs include UPA's Gerald McBoing Boing (1956–1957), Soundac's Colonel Bleep (1957–1960, the first animated TV series in color), Terrytoons's Tom Terrific (1958), and Jay Ward's The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends (1959–1964).

In contrast to the international film market (developed during the silent era when language problems were limited to title cards), TV-pioneering in most countries (often connected to radio broadcasting) focused on domestic production of live programs. Rather than importing animated series that usually would have to be dubbed, children's programming could more easily and more cheaply be produced in other ways (for instance, featuring puppetry). One notable method was the real-time "animation" of cutout figures in Captain Pugwash (1957) on the BBC. One of the few early animated series for TV that was seen abroad was Belvision Studios' Les Aventures de Tintin, d'après Hergé (Hergé's Adventures of Tintin) (Belgium 1957–1964, directed by Ray Goossens), broadcast by the BBC in 1962 and syndicated in the United States from 1963 to 1971.

Theatrical short cartoons in the 1950s[]

Warner Bros. introduced new characters Sylvester Jr. (1950), Speedy Gonzales (1953), Ralph Wolf and Sam Sheepdog (1953), and Tasmanian Devil (1954).

Theatrical feature animation in the 1950s[]

Disney[]

After a string of package features and live-action/animation combos, Disney returned to fully animated feature films with Cinderella in 1950 (the first since Bambi). Its success practically saved the company from bankruptcy. It was followed by Alice in Wonderland (1951), which flopped at the box office and was critically panned. Peter Pan (1953) and Lady and the Tramp (1955) were hits. The ambitious, much delayed and more expensive Sleeping Beauty (1959) lost money at the box office and caused doubts about the future of Walt Disney's animation department. Like "Alice in Wonderland" and most of Disney's flops, it would later be commercially successful through re-releases and would eventually be regarded as a true classic.

Non-US[]

- Jeannot l'intrépide (Johnny the Giant Killer) (France, 1950 feature)

- Le Roi et l'Oiseau (The King and the Mockingbird) (France, 1952 unfinished feature release, 1980 finished release, influential for Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata)

- Animal Farm (U.K./U.S.A., 1954 feature)

- 乌鸦为什么是黑的 (Why Is the Crow Black-Coated) (China, 1956 short film, Venice Film Festival)

- Снежная королева (The Snow Queen) (Soviet Union, 1957 feature)

- Krtek (Mole) (Czechoslovakia, 1956 short film series)

- 白蛇伝 (Panda and the Magic Serpent) (Japan, 1958 feature)

- 少年猿飛佐助 (Magic Boy) (Japan, 1959 feature, first anime released in U.S. in 1961)

1960s[]

US animated TV series and specials in the 1960s[]

Total Television was founded in 1959 to promote General Mills products with original cartoon characters in Cocoa Puffs commercials (1960–1969) and the General Mills-sponsored TV series King Leonardo and His Short Subjects (1960–1963, repackaged shows until 1969), Tennessee Tuxedo and His Tales (1963–1966, repackaged shows until 1972), The Underdog Show (1964–1967, repackaged shows until 1973) and The Beagles (1966–1967). Animation for all series was produced at Gamma Studios in Mexico. Total Television stopped producing after 1969, when General Mills no longer wanted to sponsor them.

Many of the American animated TV series from the 1960s to 1980s were based on characters and formats that had already proved popular in other media. UPA produced The Dick Tracy Show (1961–1962), based on the comic books. Filmation, active from 1962 to 1989, created few original characters, but many adaptations of DC Comics, live-action TV series (including Lassie's Rescue Rangers (1973–1975) and Star Trek: The Animated Series), some live-action features (including Journey to the Center of the Earth (1967–1969), and much more). Grantray-Lawrence Animation was the first studio to adapt Marvel Comics superheroes in 1966. Pop groups got animated versions in The Beatles (1965–1966) and Rankin/Bass's The Jackson 5ive (1971–1972) and The Osmonds (1972). Hanna-Barbera turned comedians into cartoon characters with Laurel and Hardy (1966–1967) and The Abbott and Costello Cartoon Show (1967–1968). Format Films' The Alvin Show (1961–1962) was a spin-off of a 1958 novelty song and the subsequent comic books with redesigned versions of Alvin and the Chipmunks. Other series contained unlicensed appropriations. For instance, Hanna-Barbera's The Flintstones (1960–1966) was clearly inspired by sitcom The Honeymooners and creator Jackie Gleason considered suing Hanna-Barbera, but he did not want to be known as "the guy who yanked Fred Flintstone off the air".[91]

The Flintstones was the first prime-time animated series and became immensely popular, it remained the longest-running network animated television series until that record was broken three decades later. Hanna-Barbera scored more hits with The Yogi Bear Show (1960–1962), The Jetsons (1962–1963, 1985, 1987) and Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! (1969–1970, later followed by other Scooby-Doo series).

From around 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., then Robert F. Kennedy's and other violent acts made the public less at ease with violence in entertainment, networks hired censors in order to ban anything deemed too violent or suggestive from children's programming.[92]

Apart from regular TV series, there were several noteworthy animated television (holiday) specials, starting with UPA's Mister Magoo's Christmas Carol (1962), followed a few years later by other classic examples such as the string of Bill Melendez' Peanuts specials (1965-2011, based on Charles M. Schulz's comic strip), and Chuck Jones's How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1966, based on the story by Dr. Seuss).

Cambria Productions[]

Cambria Productions only occasionally used traditional animation and would often resort to camera movements, real-time movements between foreground and background cels, and integration of live-action footage. Creator Clark Haas explained: "We are not making animated cartoons. We are photographing 'motorized movement' and—the biggest trick of all—combining it with live action.... Footage that Disney does for $250,000 we do for $18,000."[93] Their most famous trick was the Syncro-Vox technique of superimposing talking lips on the faces of cartoon characters in lieu of animating mouths synchronized to dialogue. This optical printing system had been patented in 1952 by Cambria partner and cameraman Edwin Gillette and was first used for popular "talking animal" commercials. The method would later be widely used for comedic effect, but Cambria used it straight in their series Clutch Cargo (1959–1960), Space Angel (1962) and Captain Fathom (1965). Thanks to imaginative stories, Clutch Cargo was a surprise hit. Their last series The New 3 Stooges (1965–1966) no longer used Syncro-Vox. It contained 40 new live-action segments with the original Three Stooges that was spread and repeated throughout 156 episodes together with new animation (occasionally causing people to turn off their TV when live-action footage was repeated, convinced that they had already seen the episode).

US theatrical animation in the 1960s[]

For One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) production costs were restrained, helped by the xerography process that eliminated the inking process. Although the relatively sketchy look was not appreciated by Walt Disney personally, it did not bother critics or audiences and the film was another hit for the studio. The Sword in the Stone (1963) was another financial success, but over the years it has become one of the least known Disney features. It was followed by the live-action/animation hit Mary Poppins (1964) which received 13 Academy Awards nominations, including Best Picture. Disney's biggest animated feature of the 1960s was The Jungle Book (1967) which was both a critical and commercial success. This was also the final film that was overseen by Walt Disney before his death in 1966. Without Walt's imagination and creative endeavour, the animation teams were unable to produce many successful films during the 1970s and 1980s. This was until the release of The Little Mermaid (1989), 22 years later.

UPA produced their first feature 1001 Arabian Nights (1959) (starring Mr. Magoo as Alladin's uncle) for Columbia Pictures, with little success. They tried again with Gay Purr-ee in 1962, released by Warner Bros.. It was well received by critics, but failed at the box office and would be the last feature the studio ever made.

Decline of the theatrical short cartoon[]

The Supreme Court ruling of the Hollywood Anti-trust Case of 1948 prohibited "block bookings" in which hit feature films were exclusively offered to theatre owners in packages together with newsreels and cartoons or live-action short films. Instead of receiving a reasonable percentage of a package deal, short cartoons had to be sold separately for the prices that theatre owners were willing to pay for them. Short cartoons were relatively expensive and could now be dropped from the program without people losing interest in the main feature, which became a sensible way to reduce costs when more and more potential movie-goers seemed to stay at home to watch movies on their television sets. Most cartoons had to be re-released several times to recoup the invested budget.[94][95] By the end of the 1960s most studios had ceased producing theatrical cartoons. Even Warner Bros. and Disney, with occasional exceptions, stopped making short theatrical cartoons after 1969. Walter Lantz was the last of the classic cartoon producers to give up, when he closed his studio in 1973.

DePatie–Freleng[]

DePatie–Freleng Enterprises, founded by Friz Freleng and David H. DePatie in 1963 after Warner Bros. closed their animation department, was the only studio who found new success with short theatrical cartoon series after the 1950s. They created Pink Panther in 1963 for the opening and closing credits of the live-action The Pink Panther film series featuring Peter Sellers. Its success led to a series of short films (1964–1980) and TV series (1969–1980). Pink Panther was followed by the spin-off The Inspector (1965–1969), The Ant and the Aardvark (1969–1971) and a handful of other theatrical series. The Dogfather (1974–1976) was the last new series, but Pink Panther cartoons appeared in theaters until 1980, shortly before the demise of the studio in 1981. From 1966 to 1981 DePatie–Freleng also produced many TV series and specials.

Rise of anime[]

Japan was notably prolific and successful with their own style of animation, which became known in the English language initially as Japanimation and eventually as anime. In general, anime was developed with limited-animation techniques that put more emphasis on the aesthetic quality than on movement, in comparison to US animation. It also applies a relatively "cinematic" approach with zooming, panning, complex dynamic shots and much attention for backgrounds that are instrumental to creating atmosphere.

Anime was first domestically broadcast on TV in 1960. Export of theatrical anime features started around the same time. Within a few years, several anime TV series were made that would also receive varying levels of airplay in the United States and other countries, starting with the highly influential 鉄腕アトム (Astro Boy) (1963), followed by ジャングル大帝 (Kimba the White Lion) (1965–1966), エイトマン (8th Man) (1965), 魔法使いサリー (Sally the Witch) (1966–1967) and マッハGoGoGo (Mach GoGoGo a.k.a. Speed Racer) (1967).

The domestically popular サザエさん / Sazae-san started in 1969 and is probably the longest-running animated TV show in the world, with more than 7,700 episodes.

Early adult-oriented and counterculture animation[]

Before the end of the 1960s, hardly any adult-oriented animation had been produced. A notable exception was the pornographic short Eveready Harton in Buried Treasure (1928), presumably made by famous animators for a private party in honour of Winsor McCay, and not publicly screened until the late 1970s. After 1934, the Hays code gave filmmakers in the United States little leeway to release risky material, until the code was replaced by the Motion Picture Association of America film rating system in 1968. While television programming of animation had made most people think of it as a medium for children or for family entertainment, new theatrical animations proved otherwise.

Arguably, the philosophical, psychological, and sociological overtones of the Peanuts TV specials were relatively adult-oriented, while the specials were also enjoyable for children. In 1969 director Bill Mendelez expanded the success of the series to cinemas with A Boy Named Charlie Brown. The theatrical follow-up Snoopy Come Home (1972) was a box-office flop, despite positive reviews. Race for Your Life, Charlie Brown (1977) and Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown (and Don't Come Back!!) (1980) were the only other theatrical traditionally animated feature films for Peanuts, while the TV specials continued until 2011.

The anti-establishment counterculture boom at the end of the 1960s impacted Hollywood early on. In animation, anti-war sentiments were clearly present in several short underground films like Ward Kimball's Escalation (1968) (made independently from his employment at Disney) and the parody Mickey Mouse in Vietnam (1969). The less political parody Bambi meets Godzilla (1969) by Marv Newland, another underground short film for adults, is considered a great classic and was included in The 50 Greatest Cartoons (1994) (based on a poll of 1,000 people working in the animation industry).

The popularity of psychedelia reportedly made the 1969 re-release of Disney's Fantasia popular among teenagers and college students, and the film started to make a profit. Similarly, Disney's Alice in Wonderland became popular with TV screenings in this period and with its 1974 theatrical re-release.

Also influenced by the psychedelic revolution, The Beatles' animated musical feature Yellow Submarine (1968) showed a broad audience how animation could be quite different from the well known television cartoons and Disney features. Its distinctive design came from art director Heinz Edelman. The film received widespread acclaim and would prove to be influential. Peter Max further popularized a similar visual style in his artworks.

Non-US animation in the 1960s[]

- わんぱく王子の大蛇退治 (The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon) (Japan, 1963 feature)

- 大鬧天宮 (Havoc in Heaven) (China, 1963 feature)

- ガリバーの宇宙旅行 (Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon) (Japan, 1965 feature)

- Calimero (Italy/Japan 1963–1972, TV series)

- Belvision's Pinocchio in Outer Space (Belgium/USA 1965, feature directed by Ray Goossens)

- West and Soda (Italy 1965, first feature by Bruno Bozzetto)

1970s[]

Breakthrough of adult-oriented and counterculture feature animation[]

Ralph Bakshi thought that the idea of "grown men sitting in cubicles drawing butterflies floating over a field of flowers, while American planes are dropping bombs in Vietnam and kids are marching in the streets, is ludicrous."[96] He therefore created a more sociopolitical type of animation, starting with Fritz the Cat (1972), based on Robert Crumb's comic books and the first animated feature to receive an X-rating. The X-rating was used to promote the film and it became the highest-grossing independent animated film of all time. The success of Heavy Traffic (1973) made Bakshi the first since Disney to have two financially successful animated feature films in a row. The film utilized an artistic blend of techniques with still photography as the background in parts, a live-action scene of models with painted faces rendered in negative cinematography, a scene rendered in very limited sketchy animation that was only partly colored, detailed drawing, archival footage, and most characters animated in a consistent cartoon style throughout it all, except the last ten minutes which were fully filmed as a standard live-action film. He continued to experiment with different techniques in most of his next projects. His next projects Hey Good Lookin' (finished in 1975, but shelved by Warner Bros. until release in an adjusted version in 1982) and Coonskin (1975, suffered from protests against its perceived racism while actually satirizing it) were far less successful, but received more appreciation later on and became cult films.