History of herbalism

The history of herbalism is closely tied with the history of medicine from prehistoric times up until the development of the germ theory of disease in the 19th century. Modern medicine from the 19th century to today has been based on evidence gathered using the scientific method. Evidence-based use of pharmaceutical drugs, often derived from medicinal plants, has largely replaced herbal treatments in modern health care. However, many people continue to employ various forms of traditional or alternative medicine. These systems often have a significant herbal component. The history of herbalism also overlaps with food history, as many of the herbs and spices historically used by humans to season food yield useful medicinal compounds,[1][2] and use of spices with antimicrobial activity in cooking is part of an ancient response to the threat of food-borne pathogens.[3]

Prehistory[]

The use of plants as medicines predates written human history. Archaeological evidence indicates that humans were using medicinal plants during the Paleolithic, approximately 60,000 years ago. (Furthermore, other non-human primates are also known to ingest medicinal plants to treat illness)[4] Plant samples gathered from prehistoric burial sites have been thought to support the claim that Paleolithic people had knowledge of herbal medicine. For instance, a 60,000-year-old Neanderthal burial site, "Shanidar IV", in northern Iraq has yielded large amounts of pollen from 8 plant species, 7 of which are used now as herbal remedies.[5] More recently Paul B. Pettitt has written that "A recent examination of the microfauna from the strata into which the grave was cut suggests that the pollen was deposited by the burrowing rodent Meriones tersicus, which is common in the Shanidar microfauna and whose burrowing activity can be observed today".[6] Medicinal herbs were found in the personal effects of Ötzi the Iceman, whose body was frozen in the Ötztal Alps for more than 5,000 years. These herbs appear to have been used to treat the parasites found in his intestines.[citation needed]

Ancient history[]

Mesopotamia[]

In Mesopotamia, the written study of herbs dates back over 5,000 years to the Sumerians, who created clay tablets with lists of hundreds of medicinal plants (such as myrrh and opium).[7]

Ancient Egypt[]

Ancient Egyptian texts are of particular interest due to the language and translation controversies that accompany texts from this era and region. These differences in conclusions stem from the lack of complete knowledge of the Egyptian language: many translations are composed of mere approximations between Egyptian and modern ideas, and there can never be complete certainty of meaning or context.[8] While physical documents are scarce, texts such as the Papyrus Ebers serve to illuminate and relieve some of the conjecture surrounding ancient herbal practices. The Papyrus consists of lists of ailments and their treatments, ranging from "disease of the limbs" to "diseases of the skin"[9] and has information on over 850 plant medicines, including garlic, juniper, cannabis, castor bean, aloe, and mandrake.[7] Treatments were mainly aimed at ridding the patient of the most prevalent symptoms because the symptoms were largely regarded as the disease itself.[10] Knowledge of the collection and preparation of such remedies are mostly unknown, as many of the texts available for translation assume the physician already has some knowledge of how treatments are conducted and therefore such techniques would not need restating.[8] Though modern understanding of Egyptian herbals stem form the translation of ancient texts, there is no doubt that trade and politics carried the Egyptian tradition to regions across the world, influencing and evolving many cultures medical practices and allowing for a glimpse into the world of ancient Egyptian medicine.[8] Herbs used by Egyptian healers were mostly indigenous in origin, although some were imported from other regions like Lebanon. Other than papyri, evidence of herbal medicine has also been found in tomb illustrations or jars containing traces of herbs.[8]

India[]

In India, Ayurveda medicine has used many herbs such as turmeric possibly as early as 4,000 BC.[11][12] Earliest Sanskrit writings such as the Rig Veda, and Atharva Veda are some of the earliest available documents detailing the medical knowledge that formed the basis of the Ayurveda system.[7] Many other herbs and minerals used in Ayurveda were later described by ancient Indian herbalists such as Charaka and Sushruta during the 1st millennium BC. The Sushruta Samhita attributed to Sushruta in the 6th century BC describes 700 medicinal plants, 64 preparations from mineral sources, and 57 preparations based on animal sources.[13]

China[]

In China, seeds likely used for herbalism have been found in the archaeological sites of Bronze Age China dating from the Shang Dynasty.[14] The mythological Chinese emperor Shennong is said to have written the first Chinese pharmacopoeia, the "Shennong Ben Cao Jing". The "Shennong Ben Cao Jing" lists 365 medicinal plants and their uses - including Ephedra (the shrub that introduced the drug ephedrine to modern medicine), hemp, and chaulmoogra (one of the first effective treatments for leprosy).[15] Succeeding generations augmented on the Shennong Bencao Jing, as in the Yaoxing Lun (Treatise on the Nature of Medicinal Herbs), a 7th-century Tang Dynasty treatise on herbal medicine.[16]

Ancient Greece and Rome[]

Hippocrates[]

The Hippocratic Corpus serves as a collection of texts that are associated with the 'Father of Western Medicine', Hippocrates of Kos. Though the actual authorship of some of these texts is disputed, each reflects the general ideals put forth by Hippocrates and his followers. The recipes and remedies included in parts of the Corpus no doubt reveal popular and prevalent treatments of the early ancient Greek period.

Though any of the herbals included in the Corpus are similar to those practiced in the religious sectors of healing, they differ strikingly in the lack of rites, prayers, or chants used in the application of remedies.[17] This distinction is truly indicative of the Hippocratic preference for logic and reason within the practices of medicine.

The ingredients mentioned in the Corpus consist of a myriad of herbs, both local to Greece and imported from exotic locales such as Arabia. While many imported goods would have been too expensive for common household use, some of the suggested ingredients include the more common and cheaper elderberries and St. John's Wort.[17]

Galen[]

Galen of Pergamon, a Greek physician practicing in Rome, was certainly prolific in his attempt to write down his knowledge on all things medical – and in his pursuit, he wrote many texts regarding herbs and their properties, most notably his Works of Therapeutics. In this text, Galen outlines the merging of each discipline within medicine that combine to restore health and prevent disease.[18] While the subject of therapeutics encompasses a wide array of topics, Galen's extensive work in the humors and four basic qualities helped pharmacists to better calibrate their remedies for the individual person and their unique symptoms.[19]

Diocles of Carystus[]

The writings of Diocles of Carystus were also extensive and prolific in nature. With enough prestige to be referred to as "the second Hippocrates", his advice in herbalism and treatment was to be taken seriously.[20] Though the original texts no longer exist, many medical scholars throughout the ages have quoted Diocles rather extensively, and it is in these fragments that we gain knowledge of his writings.[21] It is purported that Diocles actually wrote the first comprehensive herbal- this work then cited numerous times by contemporaries such as Galen, Celsus, and Soranus.[21]

Pliny[]

In what is one of the first encyclopedic texts, Pliny the Elder's Natural History serves as a comprehensive guide to nature and also presents an extensive catalog of herbs valuable in medicine. With over 900 drugs and plants listed, Pliny's writings provide a very large knowledge base upon which we may learn more about ancient herbalism and medical practices.[22] Pliny himself referred to ailments as "the greatest of all the operations of nature," and the act of treatment via drugs as impacting the "state of peace or of war which exists between the various departments of nature".[23]

Dioscordes[]

Much like Pliny, Pedanius Dioscorides constructed a pharmacopeia, De Materia Medica, consisting of over 1000 medicines produced form herbs, minerals, and animals.[24] The remedies that comprise this work were widely utilized throughout the ancient period and Dioscorides remained the greatest expert on drugs for over 1,600 years.[25]

Similarly important for herbalists and botanists of later centuries was Theophrastus' Historia Plantarum, written in the 4th century BC, which was the first systematization of the botanical world.[26][27]

Middle Ages[]

While there are certainly texts from the medieval period that denote the uses of herbs, there has been a long-standing debate between scholars as to the actual motivations and understandings that underline the creation of herbal documents during the medieval period.[28] The first point of view dictates that the information presented in these medieval texts were merely copied from their classical equivalents without much thought or understanding.[28] The second viewpoint, which is gaining traction among modern scholars, states that herbals were copied for actual use and backed by genuine understanding.[28]

Some evidence for the suggestion that herbals were utilized with knowledgeable intent, was the addition of several chapters of plants, lists of symptoms, habitat information, and plant synonyms added to texts such as the Herbarium.[29] Notable texts utilized in this time period include Bald's Leechbook, the Lacnunga, the peri didaxeon, Herbarium Apulei, Da Taxone, and Madicina de Quadrupedidus, while the most popular during this time period were the Ex Herbis Femininis, the Herbarius, and works by Dioscorides.

Benedictine monasteries were the primary source of medical knowledge in Europe and England during the Early Middle Ages. However, most of these monastic scholars' efforts were focused on translating and copying ancient Greco-Roman and Arabic works, rather than creating substantial new information and practices.[30][31] Many Greek and Roman writings on medicine, as on other subjects, were preserved by hand copying of manuscripts in monasteries. The monasteries thus tended to become local centers of medical knowledge, and their herb gardens provided the raw materials for simple treatment of common disorders. At the same time, folk medicine in the home and village continued uninterrupted, supporting numerous wandering and settled herbalists. Among these were the "wise-women" and "wise men", who prescribed herbal remedies often along with spells, enchantments, divination and advice. One of the most famous women in the herbal tradition was Hildegard of Bingen. A 12th-century Benedictine nun, she wrote a medical text called Causae et Curae.[32][33] During this time, herbalism was mainly practiced by women, particularly among Germanic tribes.[34]

There were three major sources of information on healing at the time including the Arabian School, Anglo-Saxon leechcraft, and Salerno. A great scholar of the Arabian School was Avicenna, who wrote The Canon of Medicine which became the standard medical reference work of the Arab world. "The Canon of Medicine is known for its introduction of systematic experimentation and the study of physiology, the discovery of contagious diseases and sexually transmitted diseases, the introduction of quarantine to limit the spread of infectious diseases, the introduction of experimental medicine, clinical trials, and the idea of a syndrome in the diagnosis of specific diseases. ...The Canon includes a description of some 760 medicinal plants and the medicine that could be derived from them."[35] With Leechcraft, though bringing to mind part of their treatments, leech was the English term for medical practitioner.[34] Salerno was a famous school in Italy centered around health and medicine. A student of the school was Constantine the African, credited with bringing Arab medicine to Europe.[34]

Translation of herbals[]

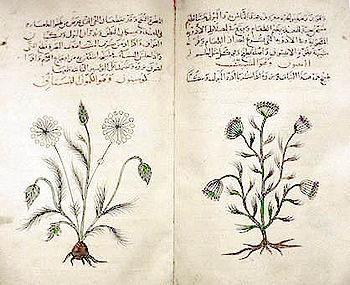

During the Middle Ages, the study of plants began to be based on critical observations. "In the 16th and 17th century an interest in botany revived in Europe and spread to America by way of European conquest and colonization."[36] Philosophers started to act as herbalists and academic professors studied plants with great depth. Herbalists began to explore the use of plants for both medicinal purposes and agricultural uses. Botanists in the Middle Ages were known as herbalists; they collected, grew, dried, stored, and sketched plants. Many became experts in identifying and describing plants according to their morphology and habitats, as well as their usefulness. These books, called herbals included beautiful drawings and paintings of plants as well as their uses.

At that time both botany and the art of gardening stressed the utility of plants for man; the popular herbal, described the medical uses of plants.[36] During the Middle Ages, there was an expansion of book culture that spread through the medieval world. The phenomenon of translation is well-documented, from its beginnings as a scholarly endeavor in Baghdad as early as the eighth century to its expansion throughout European Mediterranean centers of scholarship by the eleventh and twelfth centuries.[37] The process of translation is collaborative effort, requiring a variety of people to translate and add to them. However, how the Middle Ages viewed nature seems to be a mystery.

Translation of text and image has provided numerous versions and compilations of individual manuscripts from diverse sources, old and new. Translation is a dynamic process as well as a scholarly endeavor that contributed great to science in the Middle Ages; the process naturally entailed continuous revisions and additions.[37] The Benedictine monasteries were known for their in-depth knowledge of herbals. These gardens grew the herbs which were considered to be useful for the treatment of the various human ills; the beginnings of modern medical education can be connected with monastic influence.[38] Monastic academies were developed and monks were taught how to translate Greek manuscripts into Latin.

Knowledge of medieval botanicals was closely related to medicine because the plant's principal use was for remedies.[39] Herbals were structured by the names of the plants, identifying features, medicinal parts of plant, therapeutic properties, and some included instructions on how to prepare and use them. For medical use of herbals to be effective, a manual was developed. Dioscorides' De material medica was a significant herbal designed for practical purposes.[39]

Theophrastus wrote more than 200 papers describing the characteristics of over 500 plants. He developed a classification system for plants based on their morphology such as their form and structure.[38] He described in detail pepper, cinnamon, bananas, asparagus, and cotton. Two of his best-known works, Enquiry into Plants and The Causes of Plants, have survived for many centuries and were translated into Latin. He has been referred to as the "grandfather of botany".[38] Crateuas was the first to produce a pharmacological book for medicinal plants, and his book influenced medicine for many centuries.[38] A Greek physician, Pedanius Dioscorides described over 600 different kinds of plants and describes their useful qualities for herbal medicine, and his illustrations were used for pharmacology and medicine as late as the Renaissance years.

Monasteries established themselves as centers for medical care. Information on these herbals and how to use them was passed on from monks to monks, as well as their patients.[40] These illustrations were of no use to everyday individuals; they were intended to be complex and for people with prior knowledge and understanding of herbal. The usefulness of these herbals have been questioned because they appear to be unrealistic and several plants are depicted claiming to cure the same condition, as “the modern world does not like such impression."[40] When used by experienced healers, these plants can provide their many uses. For these medieval healers, no direction was needed their background allowed them to choose proper plants to use for a variety of medical conditions. The monk's purpose was to collect and organize text to make them useful in their monasteries. Medieval monks took many remedies from classical works and adapted them to their own needs as well as local needs. This may be why none of the collections of remedies we have presently agrees fully with another.[40]

Another form of translation was oral transmission; this was used to pass medical knowledge from generation to generation. A common misconception is that one can know early medieval medicine simply by identifying texts, but it is difficult to compose a clear understanding of herbals without prior knowledge.[40][page needed] There are many factors that played in influenced in the translation of these herbals, the act of writing or illustrating was just a small piece of the puzzle, these remedies stems from many previous translations the incorporated knowledge from a variety of influences.

Early modern era[]

The 16th and 17th centuries were the great age of herbals, many of them available for the first time in English and other languages rather than Latin or Greek. The 18th and 19th centuries saw more incorporation of plants found in the Americas, but also the advance of modern medicine.

16th century[]

The first herbal to be published in English was the anonymous Grete Herball of 1526. The two best-known herbals in English were The Herball or General History of Plants (1597) by John Gerard and The English Physician Enlarged (1653) by Nicholas Culpeper. Gerard's text was basically a pirated translation of a book by the Belgian herbalist Dodoens and his illustrations came from a German botanical work. The original edition contained many errors due to faulty matching of the two parts. Culpeper's blend of traditional medicine with astrology, magic, and folklore was ridiculed by the physicians of his day, yet his book - like Gerard's and other herbals - enjoyed phenomenal popularity. The Age of Exploration and the Columbian Exchange introduced new medicinal plants to Europe. The Badianus Manuscript was an illustrated Mexican herbal written in Nahuatl and Latin in the 16th century.[41]

17th century[]

The second millennium, however, also saw the beginning of a slow erosion of the pre-eminent position held by plants as sources of therapeutic effects. This began with the Black Death, which the then dominant Four Element medical system proved powerless to stop. A century later, Paracelsus introduced the use of active chemical drugs (like arsenic, copper sulfate, iron, mercury, and sulfur).

18th century[]

In the Americas, herbals were relied upon for most medical knowledge with physicians being few and far between. These books included almanacs, Dodoens' New Herbal, Edinburgh New Dispensatory, Buchan's Domestic Medicine, and other works.[42] Aside from European knowledge on American plants, Native Americans shared some of their knowledge with colonists, but most of these records were not written and compiled until the 19th century. John Bartram was a botanist that studied the remedies that Native Americans would share and often included bits of knowledge of these plants in printed almanacs.[42]

19th century[]

The formalization of pharmacology in the 19th century led to greater understanding of the specific actions drugs have on the body. At that time, Samuel Thompson was an uneducated but well respected herbalist who influenced professional opinions so much that Doctors and Herbalists would refer to themselves as Thompsonians. They distinguished themselves from "regular" doctors of the time who used calomel and bloodletting, and led to a brief renewal of the empirical method in herbal medicine.[43]

Modern era[]

Traditional herbalism has been regarded as a method of alternative medicine in the United States since the Flexner Report of 1910 led to the closing of the eclectic medical schools where botanical medicine was exclusively practiced. In China, Mao Zedong reintroduced Traditional Chinese Medicine, which relied heavily on herbalism, into the health care system in 1949. Since then, schools have been training thousands of practitioners – including Americans – in the basics of Chinese medicines to be used in hospitals.[43] While Britain in the 1930s was experiencing turbulence over the practice of herbalism, in the United States, government regulation began to prohibit the practice.[44]

"The World Health Organization estimated that 80% of people worldwide rely on herbal medicines for some part of their primary health care. In Germany, about 600 to 700 plant based medicines are available and are prescribed by some 70% of German physicians."[45]

The practice of prescribing treatments and cures to patients requires a legal medical license in the United States of America, and the licensing of these professions occurs on a state level. "There is currently no licensing or certification for herbalists in any state that precludes the rights of anyone to use, dispense, or recommend herbs."[46]

"Traditional medicine is a complex network of interaction of both ideas and practices, the study of which requires a multidisciplinary approach."[47] Many alternative physicians in the 21st century incorporate herbalism in traditional medicine due to the diverse abilities plants have and their low number of side effects.

See also[]

- Physic garden

- History of pharmacy

- Ethnobotany

- Medieval medicine of Western Europe

- Traditional African medicine

References[]

- ^ Tapsell LC, Hemphill I, Cobiac L, et al. (August 2006). "Health benefits of herbs and spices: the past, the present, the future". Med. J. Aust. 185 (4 Suppl): S4–24. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00548.x. PMID 17022438. S2CID 9769230.

- ^ Lai PK, Roy J (June 2004). "Antimicrobial and chemopreventive properties of herbs and spices". Curr. Med. Chem. 11 (11): 1451–60. doi:10.2174/0929867043365107. PMID 15180577.

- ^ Billing, Jennifer; Sherman, PW (March 1998). "Antimicrobial functions of spices: why some like it hot". Q Rev Biol. 73 (1): 3–49. doi:10.1086/420058. PMID 9586227. S2CID 22420170.

- ^ Sumner, Judith (2000). The Natural History of Medicinal Plants. Timber Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-88192-483-1.

- ^ Solecki, Ralph S. (November 1975). "Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Flower Burial in Northern Iraq". Science. 190 (4217): 880–881. Bibcode:1975Sci...190..880S. doi:10.1126/science.190.4217.880. S2CID 71625677.).

- ^ Pettitt, Paul B. (2002). "The Neanderthal Dead, exploring mortuary variability in middle paleolithic eurasia" (PDF). Before Farming. 1 (4): 19 note 8. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sumner, Judith (2000). The Natural History of Medicinal Plants. Timber Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-88192-483-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Nunn, JF (1996). "Ancient Egyptian medicine". Transactions of the Medical Society of London. 113: 57–68. OCLC 122129525. PMID 10326089.

- ^ "THE". 2005-02-26. Archived from the original on February 26, 2005. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- ^ Von Klein, Carl H. (1905). The Medical Features of the Papyrus Ebers. Chicago: Press of the American Medical Association.

- ^ Susan G. Wynn; Barbara Fougère (2007). Veterinary Herbal Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-323-02998-8.

- ^ Aggarwal, Bharat B.; Sundaram, Chitra; Malani, Nikita; Ichikawa, Haruyo (2007). "Curcumin: The Indian Solid Gold". The Molecular Targets and Therapeutic Uses of Curcumin in Health and Disease. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 595. pp. 1–75. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_1. ISBN 978-0-387-46400-8. PMID 17569205.

- ^ Girish Dwivedi, Shridhar Dwivedi (2007). History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence (PDF). National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-10-10. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ Hong, Francis (2004). "History of Medicine in China" (PDF). McGill Journal of Medicine. 8 (1): 7984. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-01.

- ^ Sumner, Judith (2000). The Natural History of Medicinal Plants. Timber Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-88192-483-1.

- ^ Wu, Jing-Nuan (2005). An Illustrated Chinese Materia Medica. Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 9780195140170.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Totelin, Laurence M.V (2009). Hippocratic Recipes: Oral and Written Transmission of Pharmacological Knowledge in Fifth and Fourth Century Greece. Leiden and Boston: Brill. p. 125. ISBN 978-90-474-2486-4.

- ^ Hankinson, R.J (2008). "Therapeutics- Van Der Eijk". The Cambridge Companion to Galen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-82691-4.

- ^ Hankinson, R.J (2008). "Drugs and Pharmacology- Vogt". The Cambridge Companion to Galen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139826914.

- ^ Jaeger, Werner (July 1, 1940). "Diocles of Carystus: A New Pupil of Aristotle". The Philosophical Review. 49 (4): 393–414. doi:10.2307/2181272. JSTOR 2181272.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eijk, Philip J (2000). Diocles of Carystus: A Collection of the Fragments with Translation and Commentary. Brill. pp. vii. ISBN 978-90-04-10265-1.

- ^ The Elder, Pliny; Rackham, Harris (1938). Natural History. London: W. Heinemann.

- ^ The Elder, Pliny; Riley, Henry T; Bostock, John (1855). The Natural History of Pliny. 4. London: H.G. Bohn. p. 206.

- ^ Hale-White, William (1902). Materia Medica, Pharamcy, Pharmacology, and Therapeutics. J. and A. Churchill.

- ^ Riddle, John M. (2011). Dioscorides on Pharmacy and Medicine. University of Texas. ISBN 978-0-292-72984-1.

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Theophrastus". Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 787.

- ^ Grene, Marjorie (2004). The philosophy of biology: an episodic history. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-521-64380-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Voigts, Linda E. (June 1, 1979). "Anglo-Saxon Plant Remedies and the Anglo-Saxons". Isis. 70 (2): 255, 252, 254. doi:10.1086/352199. JSTOR 230791. PMID 393654. S2CID 3201828.

- ^ Van Arsdall, Anne (2002). Medieval Herbal Remedies: the Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine. New York: Psychology Press. p. 119.

- ^ Arsdall, Anne V. (2002). Medieval Herbal Remedies: The Old English Herbarium and Anglo-Saxon Medicine. Psychology Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 9780415938495.

- ^ Mills, Frank A. (2000). "Botany". In Johnston, William M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Monasticism: M-Z. Taylor & Francis. p. 179. ISBN 9781579580902.

- ^ Ramos-e-Silva Marcia (1999). "Saint Hildegard Von Bingen (1098–1179) "The Light Of Her People And Of Her Time"". International Journal of Dermatology. 38 (4): 315–320. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00617.x. PMID 10321953. S2CID 13404562.

- ^ Truitt Elly R (2009). "The Virtues Of Balm In Late Medieval Literature". Early Science and Medicine. 14 (6): 711–736. doi:10.1163/138374209x12542104913966. PMID 20509358.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "History of Western Herbalism | Dr. Christopher Hobbs". www.christopherhobbs.com. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ^ Cantin, Candis (June 25, 2019). "A History of Herbalism for Herbalists, Part 1: How the Arabs Saved Greek Sciences". www.planetherbs.com. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moore, R. (1998). Botany (2nd ed.). New York: WCB/McGraw-Hill

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hoffman E. R. (2012). "Translating Image and Text in the Medieval Mediterranean World between the Tenth and Thirteenth Centuries". Medieval Encounters. 18 (4/5): 584–623. doi:10.1163/15700674-12342120.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Krebs, Robert E. (2004). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32433-8.[page needed]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lindberg, D. C. (2007). The beginnings of Western science: the European scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context, 600 B.C. to A.D. 1450. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Arsdall, A. (2002). Medieval herbal remedies: the Old English herbarium and Anglo-Saxon medicine. New York: Routledge.

- ^ Gimmel Millie (2008). "Reading Medicine In The Codex De La Cruz Badiano". Journal of the History of Ideas. 69 (2): 169–192. doi:10.1353/jhi.2008.0017. PMID 19127831. S2CID 46457797.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Herbal Medicine: The Medical Botany of John Bartram". www.healthy.net. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ph.D., Roger W. Wicke. "History of herbology, herbalism | RMHI". www.rmhiherbal.org. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ^ Brown, P S (1985-01-01). "The vicissitudes of herbalism in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Britain". Medical History. 29 (1): 71–92. doi:10.1017/s0025727300043751. ISSN 0025-7273. PMC 1139482. PMID 3883085.

- ^ "Herbal medicine". University of Maryland Medical Center. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ^ Hernandez, Mimi. "Legal and Regulatory FAQs". American Herbalists Guild. Retrieved 2015-12-01.

- ^ Herbal Medicine in Yemen: Traditional Knowledge and Practice, and Their Value for Today's World. BRILL. 2012. ISBN 978-90-04-23207-5.[page needed]

Further reading[]

- Arsdall, A (2002). Medieval herbal remedies: the Old English herbarium and Anglo-Saxon medicine.

- Hoffman, E.R. (2012). "Translating Image and Text in the Medieval Mediterranean World between the Tenth and Thirteenth Centuries. Medieval Encounters": 584–623. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Krebbs (2004). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (PDF). Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313324338.

- Lindberg, D.C. (2007). The beginnings of Western science: the European scientific tradition in philosophical, religious, and institutional context, 600 B.C. to A.D. 1450. University of Chicago Press.

- Moore, R (1998). Botany (2nd ed.). New York.

- Herbalism

- Botany

- History of botany