History of the United Nations

The history of the United Nations as an international organization has its origins in World War II. Since then its aims and activities have expanded to make it the archetypal international body in the early 21st century.

Background[]

The first international organizations were created to enable countries to cooperate on specific matters. The International Telegraph Union was founded in 1865 and the Universal Postal Union was established in 1874. Both are now specialized agencies of the United Nations. In 1899, the Hague Convention established the Permanent Court of Arbitration, an intergovernmental organization which began work in 1902.[1]

The predecessor of the United Nations, the League of Nations, was conceived after World War I, and established in 1919 under the Treaty of Versailles "to promote international cooperation and to achieve peace and security." The main constitutional organs of the League were the Assembly, the Council, and the Permanent Secretariat. The Permanent Court of International Justice was provided for by the Covenant and established by the Council and Assembly. The International Labour Organization, which is also now a UN specialized agency, was created under the Treaty of Versailles as an affiliated agency of the League. In addition, there were several auxiliary agencies and commissions.[1]

Origins[]

The genesis of the United Nations is a series of conferences and declarations made by the Allies of World War II.[2][3]

London Declaration[]

On 12 June 1941, representatives of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the Union of South Africa, and of the exiled governments of Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, and Yugoslavia, as well as a representative of General de Gaulle of France met in London. They signed the Declaration of St. James's Palace expressing a vision for a postwar world order.[4] This was the first step that led up to the founding of the United Nations.[5]

The United Kingdom and the USSR agreed an alliance the next month with the Anglo-Soviet Agreement.[6]

Atlantic Charter[]

The Atlantic Conference followed on 9-12 August 1941 at which American President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill laid out this vision in a more detailed form in the Atlantic Charter. At the subsequent meeting of the Inter-Allied Council in London on 24 September 1941, the eight governments in exile of countries under Axis occupation, together with the Soviet Union and representatives of the Free French Forces, unanimously adopted adherence to the common principles of policy set forth by Britain and United States.[7][8]

Declaration by United Nations[]

President Roosevelt first suggested using the name United Nations, to refer to the Allies of World War II, to Prime Minister Churchill during the latter's three-week visit to the White House in December 1941. Roosevelt suggested the name as an alternative to "Associated Powers", a term the U.S. used in the First World War (the U.S. was never formally a member of the Allies of World War I but entered the war in 1917 as a self-styled "Associated Power"). Churchill accepted the idea and cited Lord Byron's use of the phrase "United Nations" in the poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, which referred to the Allies at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.[9][10]

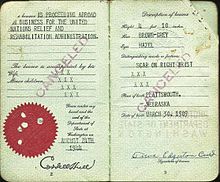

The 1942 "Declaration of The United Nations"[11] was drafted by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Roosevelt aide Harry Hopkins, while meeting at the White House on 29 December 1941. It incorporated Soviet suggestions, but left no role for France. The first official use of the term "United Nations" was on 1–2 January 1942 when 26 Governments signed the Declaration. One major change from the Atlantic Charter was the addition of a provision for religious freedom, which Stalin approved after Roosevelt insisted.[12][13] By early 1945 it had been signed by 21 more states.[14]

A JOINT DECLARATION BY THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS, CHINA, AUSTRALIA, BELGIUM, CANADA, COSTA RICA, CUBA, CZECHOSLOVAKIA, DOMINICAN REPUBLIC, EL SALVADOR, GREECE, GUATEMALA, HAITI, HONDURAS, INDIA, LUXEMBOURG, NETHERLANDS, NEW ZEALAND, NICARAGUA, NORWAY, PANAMA, POLAND, SOUTH AFRICA, YUGOSLAVIA

The Governments signatory hereto,

Having subscribed to a common program of purposes and principles embodied in the Joint Declaration of the President of the United States of America and the Prime Minister of Great Britain dated August 14, 1941, known as the Atlantic Charter,

Being convinced that complete victory over their enemies is essential to defend life, liberty, independence and religious freedom, and to preserve human rights and justice in their own lands as well as in other lands, and that they are now engaged in a common struggle against savage and brutal forces seeking to subjugate the world,

DECLARE:

(1) Each Government pledges itself to employ its full resources, military or economic, against those members of the Tripartite Pact and its adherents with which such government is at war.

(2) Each Government pledges itself to cooperate with the Governments signatory hereto and not to make a separate armistice or peace with the enemies.

The foregoing declaration may be adhered to by other nations which are, or which may be, rendering material assistance and contributions in the struggle for victory over Hitlerism.[15]

During the war, the United Nations became the official term for the Allies. To join, countries had to sign the Declaration and declare war on the Axis.[16]

The Anglo-Soviet Treaty in 1942 formed a twenty-year political alliance between the British Empire and the Soviet Union.[17]

Moscow and Tehran conferences[]

US President Franklin D. Roosevelt was the chief promoter of the Four Powers idea.[18] The first commitments to the creation of a future international organization emerged in declarations signed at the 1943 wartime Allied conferences. The Moscow Conference resulted in the Moscow Declarations, including the Declaration of the Four Nations on General Security, which omitted any discussion of the potentially-controversial establishment of a permanent peacekeeping force after the war. Instead, its stated aim was simply the creation "at the earliest possible date of a general international organization." It was drafted by US State Department and signed by the foreign secretaries of the governments of the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and the Republic of China. This was the first formal announcement that a new international organization was being contemplated to replace the moribund League of Nations. The Tehran Conference followed on 30 October 1943 at which Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin met and discussed the idea of a post-war international organization.

Dumbarton Oaks and Yalta conferences[]

The Allies agreed to the basic structure of the new body at the Dumbarton Oaks Conference in 1944. From 21 September to 7 October, delegations from the Big Four met in Washington D.C. to elaborate plans. Representatives of the U.S. and Britain met first with the USSR and then the Republic of China, since the USSR would not meet with China directly.[19] Those and later talks produced proposals outlining the purposes of the new international organization, its membership and organs, as well as arrangements to maintain international peace and security and international economic and social cooperation. Winston Churchill urged Roosevelt to restore France to its status of a major Power after the liberation of Paris in August 1944.

For Roosevelt, creating the new organization became the most important goal for the entire war effort.[20] It was his idea that "Four Policemen" would collaborate to keep and enforce the peace. The United States, Britain, the Soviet Union and China would make the major decisions. He went public with strong advocacy in the 1944 presidential campaign, and turned detailed planning over to the State Department, where Sumner Welles and Secretary Cordell Hull worked on the project. Governments, organizations and private citizens worldwide discussed and debated these proposals.[21]

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin agreed to the establishment of the United Nations, as well as the structure of the United Nations Security Council. Stalin insisted on having a veto and FDR finally agreed; thus avoiding the fatal weakness of the League of Nations, which had theoretically been able to order its members to act in defiance of their own parliaments.[22] It was agreed that membership would be open to nations that had joined the Allies by 1 March 1945.[23] Brazil, Syria and a number of other countries qualified for membership by declarations of war on either Germany or Japan in the first three months of 1945 – in some cases retroactively.

San Francisco conference[]

On 25 April 1945, the United Nations Conference on International Organization began in San Francisco sponsored by the Big Four. The heads of the delegations of the four sponsoring countries invited the other nations to take part and took turns as chairman of the plenary meetings: Anthony Eden, of Britain, Edward Stettinius, of the United States, T. V. Soong, of China, and Vyacheslav Molotov, of the Soviet Union. At the later meetings, Lord Halifax deputized for Eden, Wellington Koo for T. V. Soong, and Andrei Gromyko for Molotov.[24] France was added as a permanent member of the Security Council at the insistence of Churchill.[25] In addition to governments, a number of non-government organizations, including Rotary International and Lions Clubs International received invitations to assist in the drafting of a charter.

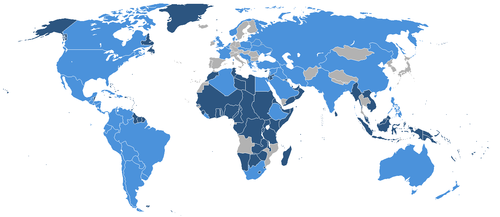

After working for two months, the fifty nations represented at the conference signed the Charter of the United Nations on 26 June. Poland, which was unable to send a representative to the conference due to political instability, signed the charter on 15 October 1945. The charter stated that before it would come into effect, it must be ratified by the governments of the Republic of China, France, the USSR, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and by a majority of the other 46 signatories. This occurred on 24 October 1945, and the United Nations was officially formed.[26]

The first meeting of the General Assembly was held in Westminster Central Hall, London, on 10 January 1946.[27] The Security Council met for the first time a week later in Church House, Westminster.[28] The League of Nations formally dissolved itself on 18 April 1946 and transferred its mission to the United Nations.

Activities[]

The United Nations has achieved considerable prominence in the social arena, fostering human rights, economic development, decolonization, health and education, for example, and interesting itself in refugees and trade.

The leaders of the UN had high hopes that it would act to prevent conflicts between nations and make future wars impossible. Those hopes have obviously not fully come to pass. From about 1947 until 1991 the division of the world into hostile camps during the Cold War made agreement on peacekeeping matters extremely difficult. Following the end of the Cold War, renewed calls arose for the UN to become the agency for achieving world peace and co-operation, as several dozen active military conflicts continued to rage across the globe. The breakup of the Soviet Union has also left the United States in a unique position of global dominance, creating a variety of new problems for the UN (See the United States and the United Nations).

Facilities[]

Potential sites for the UN Headquarters included Vienna, Switzerland, Berlin, Quebec, and the Netherlands before the delegation decided on a headquarters in the United States by December 1945.[29] Many U.S. locations vied for the honor of hosting the UN Headquarters site, such as Marin County, California; St. Louis; Boston; Chicago; Fairfield County, Connecticut; Westchester County, New York; Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens; Tuskahoma, Oklahoma; the Black Hills of South Dakota; Belle Isle in Detroit; and a site on Navy Island straddling the U.S.-Canada border.[30][31][32] San Francisco, where the UN founding conference was held, was favored by Australia, New Zealand, China, and the Philippines due to the city's proximity to their countries.[31] The UN and many of its delegates seriously considered Philadelphia for the headquarters; the city offered to donate land in several select sites, including Fairmount Park, Andorra, and a location in Center City, Philadelphia, that would have placed the headquarters along a mall extending from Independence Hall to Penn's Landing.[31]

In 1946, John D. Rockefeller III and Laurance Rockefeller each offered their respective residences in Kykuit in Mount Pleasant, New York, as headquarters for the UN, but the proposals were vetoed as the sites were too isolated from Manhattan.[33] The Soviet Union vetoed Boston due to the denunciations of Soviet expansion by John E. Swift, a Massachusetts judge and Supreme Knight of the Knights of Columbus.[34]

Prior to the completion of the UN's current headquarters, it used part of a Sperry Gyroscope Company factory in Lake Success, New York, for most of its operations, including the Security Council, between 1946 and 1952.[35][36] Between 1946 and 1950, the General Assembly, however, met at the New York City Building in Flushing Meadows, which had been built for the 1939 New York World's Fair and is now the site of the Queens Museum.[37][38]

New York City Planning Commissioner Robert Moses convinced Nelson Rockefeller to purchase a 17 and 18 acres (6.9 and 7.3 ha) piece of land along the East River in New York City from real estate developer William Zeckendorf Sr.;[39] The purchase was funded by Nelson's father, John D. Rockefeller Jr. The Rockefeller family owned the Tudor City Apartments across First Avenue from the Zeckendorf site.[40] The UN ultimately chose the New York City site over Philadelphia after Rockefeller offered to donate the land along the East River.[30] The UN headquarters officially opened on January 9, 1951, although construction was not formally completed until October 9, 1952.[41]

Structure and associated organizations[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (January 2011) |

The basic constitutional makeup of the United Nations has changed little, though vastly increased membership has altered the functioning of some elements. The UN as a whole has generated a rich assortment of non-governmental organizations and special bodies over the years: some with a regional focus, some specific to the various peacekeeping missions, and others of global scope and importance. Other bodies (such as the International Labour Organization) formed prior to the establishment of the United Nations and only subsequently became associated with it.

Milestones[]

- In October 2015 over 350 landmarks in 60 countries were lit in blue to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the world body.[42][43][44]

See also[]

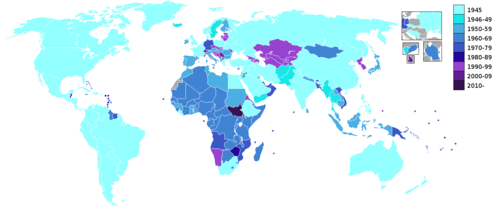

- Growth in United Nations membership

- List of members of the United Nations Security Council

- List of Allied World War II conferences

- Timeline of UN peacekeeping missions

- List of UN Secretaries-General

- Attacks on humanitarian workers

- Reform of the United Nations

References[]

- ^ a b "History of the United Nations". www.un.org. 2015-08-21. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ^ "History of The United Nations Charter". www.un.org. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- ^ Tandon, Mahesh Prasad; Tandon, Rajesh (1989). Public International Law. Allahabad Law Agency. pp. xvii, 421.

- ^ "1941: The Declaration of St. James' Palace". United Nations. 2015-08-25. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ United Nations, Dept of Public Information (1986). Everyone's United Nations. UN. p. 5. ISBN 978-92-1-100273-7.

- ^ "Anglo-Soviet Agreement". BBC Archive. Retrieved 2021-10-18.

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2011). The Evolution of International Human Rights: Visions Seen. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 140–41. ISBN 978-0-8122-2138-1.

- ^ "Inter-Allied Council Statement on the Principles of the Atlantic Charter". The Avalon Project. Lillian Goldman Law Library. 24 September 1941. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ^ "United Nations". Wordorigins.org. 3 February 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Ward, Geoffrey C.; Burns, Ken (2014). "Nothing to Conceal". The Roosevelts: An Intimate History. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 397. ISBN 978-0385353069.

- ^ "1942: Declaration of The United Nations". www.un.org. 2015-08-26. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ^ David Roll, The Hopkins Touch: Harry Hopkins and the Forging of the Alliance to Defeat Hitler (2013) pp 172-75

- ^ Robert E. Sherwood, Roosevelt and Hopkins, An Intimate History (1948) pp 447-53

- ^ Edmund Jan Osmańczyk (2003). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: T to Z. Taylor & Francis. p. 2445. ISBN 9780415939249.

- ^ Text from "The Washington Conference 1941-1942"

- ^ Stephen C. Schlesinger, Act of creation: The founding of the United Nations: A story of superpowers, secret agents, wartime allies and enemies, and their quest for a peaceful world (2003)

- ^ Plopeanu, Emanuel (2010). "Ankara – Stockholm – Bern: three types of press commentaries and interpretations about British – Soviet Treaty (May 1942)". Valahian Journal of Historical Studies (14): 133–142. ISSN 1584-2525.

- ^ Gaddis 1972, p. 24.

- ^ Hoopes and Brinkley, FDR and the Creation of the U. N. (1997) pp 148-58.

- ^ For FDR, "establishing the United nations organization was the overarching strategic goal, the absolute first priority." Townsend Hoopes; Douglas Brinkley (1997). FDR and the Creation of the U.N. Yale UP. p. 178. ISBN 0300085532.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-10-16. Retrieved 2017-06-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ John Allphin Moore Jr. and Jerry Pubantz, To Create a New World?: American Presidents & the United Nations (1999), pp 27-79.

- ^ Robert C. Hilderbrand, Dumbarton Oaks: The Origins of the United Nations and the Search for Postwar Security (UNC Press, 2001)

- ^ "1945: The San Francisco Conference". United Nations. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Stephen Schlesinger, "FDR's five policemen: creating the United Nations." World Policy Journal 11.3 (1994): 88-93. online

- ^ https://www.un.org/aboutun/sanfrancisco/history.html The 60th Anniversary of the San Francisco Conference

- ^ "History of the United Nations 1941 - 1950". United Nations. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "What is the Security Council?". United Nations. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ Glynn, Don (October 24, 2011). "Glynn - Navy Island eyed as home for U.N." Niagara Gazette. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Historical Society of Philadelphia (November 23, 2018). "When the United Nations Almost Chose Philly For Its HQ". Hidden City Philadelphia. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ a b c Atwater, Elton (April 1976). "Philadelphia's Quest to Become the Permanent Headquarters of the United Nations". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Pennsylvania: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania; University of Pennsylvania Press. JSTOR 20091055.

- ^ Mires, Charlene (April 2, 2013). "Detroit's Quixotic Bid to Host the United Nations". Foreign Policy. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Harr, John Ensor Harr & Johnson, Peter J. (1988). "Estate offered as site for the UN headquarters". The Rockefeller Century: Three Generations of America's Greatest Family. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 432–33.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Lapomarda, S.J., Vincent A. (1992). The Knights of Columbus in Massachusetts (second ed.). Norwood, Massachusetts: Knights of Columbus Massachusetts State Council. p. 41.

- ^ "Press Is Irritated by Seating in U.N." (PDF). The New York Times. August 29, 1946. p. 3. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ Schifman, Jonathan (June 1, 2017). "Did the United Nations really have headquarters on Long Island?". Newsday. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ "Flushing Meadows Corona Park". NYC Parks. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ "Designation of Building Confuses U.N. Audience" (PDF). The New York Times. October 24, 1946. p. 4. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (2010-04-25). "The U.N.: One Among Many Ideas for the Site". The New York Times. Retrieved 2017-12-26.

- ^ Boland, Ed Jr. (June 8, 2003). "F.Y.I." The New York Times. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ Hamilton, Thomas J. (1952-10-10). "WORK COMPLETED ON U. N. BUILDINGS; $68,000,000 Plant Finished -- Lie Announces a Plan to Reorganize Top Staff WORK COMPLETED ON U. N. BUILDINGS". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- ^ "World lights up in UN blue to mark Organization's milestone anniversary". UN News Centre. 22 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "Over 200 Landmarks to Light Up UN Blue on 70th Anniversary". The New York Times. 23 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "Turn the World #UNBlue". United Nations Information Centres. 2015-10-07. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

Sources[]

- Gaddis, John Lewis (1972). The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1941–1947. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12239-9.

- Hoopes, Townsend; Brinkley, Douglas (1997). FDR and the Creation of the U.N.. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08553-2.

Further reading[]

- Baehr, Peter R., and Leon Gordenker. The United Nations in the 1990s (St. Martin's Press, 1992)

- Bellamy, Alex J., and Paul D. Williams, eds. Providing Peacekeepers: The Politics, Challenges, and Future of United Nations Peacekeeping Contributions (Oxford UP, 2013)

- Bennett, A. LeRoy. Historical dictionary of the United Nations (1995) online

- Bergesen, Helge Ole, and Leiv Lunde. Dinosaurs or Dynamos: the United Nations and the World Bank at the turn of the century (Routledge, 2013)

- Bosco, David L. Five to rule them all: the UN Security Council and the making of the modern world (Oxford UP, 2009)

- Clark, Ian, and Christian Reus-Smit. "Liberal internationalism, the practice of special responsibilities and evolving politics of the security council." International Politics (2013) 50#1 pp: 38–56.

- Dykmann, Klaas. "On the Origins of the United Nations: When and How Did it Begin?." Journal of International Organizations Studies 3.1 (2012): 79–84. online

- Ferdinand, Peter. "Rising powers at the UN: an analysis of the voting behaviour of brics in the General Assembly." Third World Quarterly (2014) 35#3 pp: 376–391.

- Gall, Timothy L. and Jeneen M. Hobby, eds. Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations: vol 1 United Nations (12th ed. 2007)

- Hanhimäki, Jussi M. The United Nations: a very short introduction (Oxford UP, 2015).

- Hiscocks, Richard. The Security Council: A study in adolescence (Simon and Schuster, 1974)

- Joyce, James Avery. One increasing purpose : how the United Nations has changed the history of the world since 1945 (1984) online

- Luck, Edward C. UN Security Council: practice and promise (Routledge, 2006)

- Mazower, Mark.No Enchanted Palace: The End of Empire and the Ideological Origins of the United Nations (Princeton UP, 2009),

- Meisler, Stanley. United Nations: The First Fifty Years (1995)

- Peters, Laurence. The United Nations: history and core ideas (Springer, 2016).

- Plesch, Dan. America, Hitler and the UN: How the Allies Won World War II and Forged a Peace. (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010); the wartime alliance called the "United Nations"

- Rubin, Jacob A. Pictorial history of the United Nations (1962) online

- Rusell, Ruth B. A History of the United Nations Charter: The Role of the United States, 1940-1945 (Washington: Brookings Institution, 1958.)

- O'Sullivan, Christopher D. The United Nations: A Concise History (Krieger, 2005) online

- Phillips, Walter Ray. "United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization." Montana Law Review 24.1 (2014): 2.

- Roberts, Adam, and Dominik Zaum. Selective security: war and the United Nations Security Council since 1945 (Routledge, 2013)

- Saltford, John. The United Nations and the Indonesian takeover of West Papua, 1962-1969: the anatomy of betrayal (Routledge, 2013)

- Schlesinger, Stephen C. Act of creation: The founding of the United Nations: A story of superpowers, secret agents, wartime allies and enemies, and their quest for a peaceful world. (Westview Press, 2003).

- Vreeland, James Raymond, and Axel Dreher. The Political Economy of the United Nations Security Council: Money and Influence (Cambridge University Press, 2014)

- Weiss, Thomas G. What's Wrong with the United Nations and how to Fix it (John Wiley & Sons, 2013)

- Wuthnow, Joel. Chinese diplomacy and the UN Security Council: beyond the veto (Routledge, 2012)

Primary sources[]

- Cordier, Andrew W., and Wilder Foote, eds. Public Papers of the Secretaries General of the United Nations (4 vol; Columbia University Press, 2013)

- United Nations Archives

External links[]

- UN Intellectual History Project – Academic study of UN history

- United Nations Events Timeline

- Declaration by United Nations, January 1, 1942

- UN History Project – Website providing resources, timelines, lectures, and bibliographies of UN history

- History of the United Nations