History of the Welsh language

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2015) |

The history of the Welsh language spans over 1400 years, encompassing the stages of the language known as Primitive Welsh, Old Welsh, Middle Welsh, and Modern Welsh.

|

Origins[]

Welsh evolved from British, the Celtic language spoken by the ancient Britons. Alternatively classified as Insular Celtic or P-Celtic, it probably arrived in Britain during the Bronze Age or Iron Age and was probably spoken throughout the island south of the Firth of Forth.[1] During the Early Middle Ages the British language began to fragment due to increased dialect differentiation, evolving into Welsh and the other Brythonic languages (Breton, Cornish, and the extinct Cumbric). It is not clear when Welsh became distinct.[2]

Kenneth H. Jackson suggested that the evolution in syllabic structure and sound pattern was complete by around 550, and labelled the period between then and about 800 "Primitive Welsh".[2] This Primitive Welsh may have been spoken in both Wales and the Hen Ogledd ("Old North"), the Brythonic-speaking areas of what is now northern England and southern Scotland, and therefore been the ancestor of Cumbric as well as Welsh. Jackson, however, believed that the two varieties were already distinct by that time.[2] The earliest Welsh poetry – that attributed to the Cynfeirdd or "Early Poets" – is generally considered to date to the Primitive Welsh period. However, much of this poetry was supposedly composed in the Hen Ogledd, raising further questions about the dating of the material and language in which it was originally composed.[2]

Old Welsh[]

The next main period, somewhat better attested, is Old Welsh (Hen Gymraeg, 9th to 11th centuries); poetry from both Wales and Scotland has been preserved in this form of the language. As Germanic and Gaelic colonisation of Great Britain proceeded, the Brythonic speakers in Wales were split off from those in northern England, speaking Cumbric, and those in the south-west, speaking what would become Cornish, and so the languages diverged. The Book of Aneirin (Canu Aneirin, c. AD 600) and the Book of Taliesin (Canu Taliesin) belong to this era, though both also include some poems originally written in Primitive Welsh.

Middle Welsh[]

Middle Welsh (Cymraeg Canol) is the label attached to the Welsh of the 12th to 14th centuries, of which much more remains than for any earlier period. This is the language of nearly all surviving early manuscripts of the Mabinogion, although the tales themselves are certainly much older. It is also the language of the existing Welsh law manuscripts. Middle Welsh is reasonably intelligible, albeit with some work, to a modern-day Welsh speaker.

The famous cleric Gerald of Wales tells a story of King Henry II of England. During one of the King's many raids in the 12th century, Henry asked an old man of Pencader, Carmarthenshire, whether he thought the Welsh language had any chance:

- My Lord king, this nation may now be harassed, weakened and decimated by your soldiery, as it has so often been by others in former times; but it will never be totally destroyed by the wrath of man, unless at the same time it is punished by the wrath of God. Whatever else may come to pass, I do not think that on the Day of Direst Judgement any race other than the Welsh, or any other language, will give answer to the Supreme Judge of all for this small corner of the earth.[3]

Modern Welsh[]

Early Modern Welsh[]

Modern Welsh can be divided into two periods. The first, Early Modern Welsh ran from the early 15th century to roughly the end of the 16th century.

In the Early Modern Welsh Period the Welsh language began to be restricted in its use, such as with the passing of Henry VIII's 1536 Act of Union. Through this Act Wales was governed solely under English law. Only 150 words of this Act were concerned with the use of the Welsh language,.[4] Section 20 of the Act banned the Welsh language from being used in court proceedings[5] and those who solely spoke Welsh and did not speak English could not hold Government office. Wales was to be represented by 26 members of parliament who spoke English. Outside certain areas in Wales such as South Pembrokeshire, the majority of those living in Wales did not speak English, meaning that regularly interpreters were needed to conduct hearings.[4] Before passing the Act many Gentry and Government Officials already spoke English, however the Act codified the class ruling of the English language, with numbers who were fluent in English rising significantly after its passing.[4] Its primary function was to create uniformed control over the now United England and Wales, however it laid a foundation for a superiority of classes through the use of language. Welsh was now seen as a language spoken by the lower working classes, with those from higher classes seen superior and given roles in government for choosing to speak English over Welsh.[5] This part of the Act was not repealed until 1993 under the Welsh Languages Act, therefore the hierarchy of the English Language stayed at play well into the 20th century.

Late Modern Welsh[]

Late Modern Welsh began with the publication of William Morgan's translation of the Bible in 1588. Like its English counterpart, the King James Version, this proved to have a strong stabilizing effect on the language, and indeed the language today still bears the same Late Modern label as Morgan's language. Of course, many changes have occurred since then.

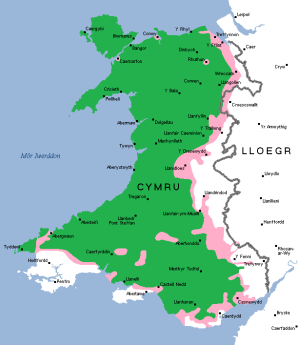

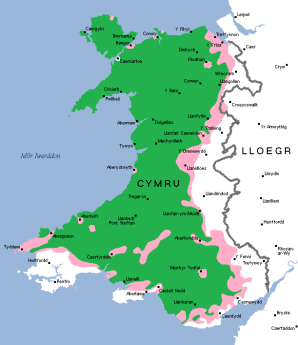

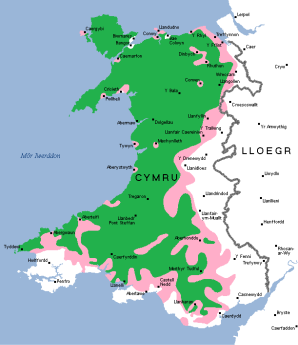

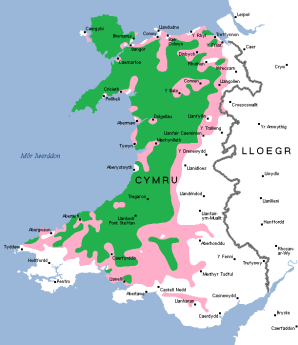

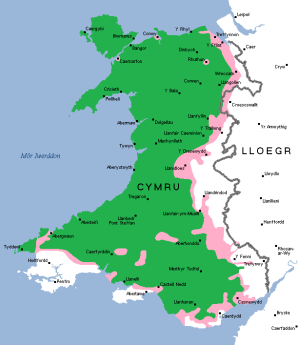

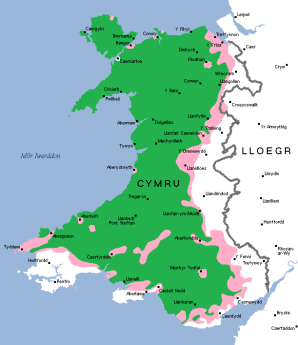

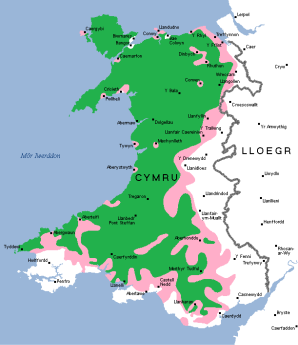

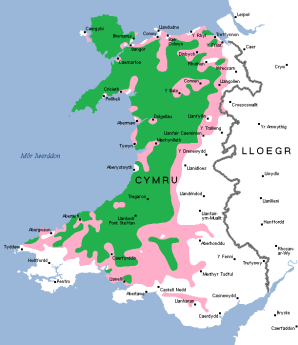

- Languages of Wales 1750 - 1900

1750

1800

1850

1900

19th century[]

The 19th century was a critical period in the history of the Welsh language and one that encompassed many contradictions. In 1800 Welsh was the main spoken language of the vast majority of Wales, with the only exceptions being some border areas and other places which had seen significant settlement, such as south Pembrokeshire; by the 1901 census this proportion had declined to a little over half of the population, though the large increase in the total population over the century (due to the effects of industrialisation and in-migration) meant that the total number of Welsh speakers grew throughout the 19th century, peaking in the 1911 census at over one million even as the proportion of the Welsh population that could speak Welsh fell below 50% for the first time.[6]

Especially when compared to other stateless languages in Europe, the language boasted an extraordinarily active press, with poetry, religious writing, biography, translations, and, by the end of the century, novels all appearing in the language, as well as countless newspapers, journals and periodicals. An ongoing interest in antiquarianism ensured the dissemination of the language's medieval poetry and prose (such as the Mabinogion). A further development was the publication of some of the first complete and concise Welsh dictionaries. Early work by Welsh lexicographic pioneers such as Daniel Silvan Evans ensured that the language was documented as accurately as possible. Modern dictionaries such as the Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru (the University of Wales Dictionary), are direct descendants of these dictionaries.

Despite these outward signs of health, it was during the nineteenth century that English replaced Welsh as the most widely spoken language within the country. Wales, particularly the South Wales Coalfield, experienced significant population growth and in-migration (primarily from England and Ireland) which changed the linguistic profile of some areas (though other areas would remain Welsh-speaking despite the changes).

Welsh held no official recognition and had limited status under the British state. It did not become officially recognised as the language of Wales until the passing of the Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011. Learning English was enthusiastically encouraged, in contrast, Welsh was not taught or used as a medium of instruction in schools, many of which actively discouraged the use of Welsh using measures such as the Welsh Not.[7] Welsh was increasingly restricted in scope to the non-conformist religious chapels, who would teach children to read and write in Sunday schools. Individuals such as Matthew Arnold championed the virtues of Welsh literature whilst simultaneously advocating the replacement of Welsh as the everyday language of the country with English, and many Welsh-speakers themselves such as David Davies and John Ceiriog Hughes advocated bilingualism, if not necessarily the extinction of Welsh.

By the end of the nineteenth century English came to prevail in the large cities of South East Wales. Welsh remained strong in the north west and in parts of mid Wales and south-west Wales. Rural Wales was a stronghold of the Welsh language – and so also were the industrial slate-quarrying communities of Caernarvonshire and Merionethshire.[8] Many of the non-conformist churches throughout Wales were strongly associated with the Welsh language.

20th century[]

By the 20th century, the numbers of Welsh speakers were shrinking at a rate which suggested that the language would be extinct within a few generations.

According to the 1911 census, out of a population of just under 2.5 million, 43.5% of those aged three years and upwards in Wales and Monmouthshire spoke Welsh (8.5% monoglot Welsh speakers, 35% bilingual in English and Welsh). This was a decrease from the 1891 census with 49.9% speaking Welsh out of a population of 1.5 million (15.1% monoglot, 34.8% bilingual). The distribution of those speaking the language however was unevenly distributed with five counties remaining overwhelmingly and predominantly Welsh speaking:

- Anglesey: 88.7% spoke Welsh while 61.0% spoke English

- Cardiganshire: 89.6% spoke Welsh while 64.1% could speak English

- Caernarfonshire: 85.6% spoke Welsh while 62.2% could speak English

- Carmarthenshire: 84.9% spoke Welsh while 77.8% could speak English

- Merionethshire: 90.3% spoke Welsh while 61.3% could speak English

Outside these five counties, a further two areas were noted as having a majority who spoke Welsh, those being:

- Denbighshire: 56.7% could speak Welsh while 88.3% could speak English

- Merthyr Tydfil County Borough 50.2% while 94.8% could speak English

1921 Census and the founding of Plaid Cymru[]

The 1921 census recorded that of the population of Wales (including Monmouthshire,) 38.7% of the population could speak Welsh while 6.6% of the overall population were Welsh monoglots. In the five predominantly Welsh speaking counties, Welsh was spoken by more than 75% of the population, and was more widely understood than English:

- Anglesey: 87.8% could speak Welsh while 67.9% could speak English

- Cardiganshire: 86.8% could speak Welsh, 72.4% could speak English

- Carmarthenshire: 84.5% could speak Welsh while 83.1% could speak English

- Merioneth: 84.3% could speak Welsh while 69.5% could speak English

- Carnarvonshire: 76.5% could speak Welsh while 73.3% could speak English

Denbighshire was the only other county where a majority could still speak Welsh, here, 51.0% could speak Welsh and 94.0% could speak English. As for larger urban areas, Aberdare was the only one where a majority could still speak Welsh, here 59.0% could speak Welsh while 95.4% could speak English. In Cardiff, Wales' capital, 5.2% of people could speak Welsh, while 99.7% of people could speak English. At a district level, Llanfyrnach rural district in Pembrokeshire had the highest percentage of Welsh speakers; at 97.5%, while Penllyn rural district in Merioneth had the highest percentage of Welsh monoglots; at 57.3%. Bethesda urban district in Carnarvonshire was the most Welsh speaking urban district in Wales; 96.6% of the district's population could speak Welsh.[10]

Plaid Cymru, The Party of Wales was founded at a 1925 National Eisteddfod meeting, held in Pwllheli, Gwynedd with the primary aim of promoting the Welsh language.[11]

Tân yn Llŷn 1936[]

Concern for the Welsh language was ignited in 1936 when the UK government decided to build an RAF training camp and aerodrome at Penyberth on the Llŷn Peninsula in Gwynedd. The events surrounding the protest became known as Tân yn Llŷn (Fire in Llŷn).[12] The UK government had settled on Llŷn as the location for this military site after plans for similar bases in Northumberland and Dorset had met with protests.[13]

However, UK Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin refused to hear the case against basing this RAF establishment in Wales, despite a deputation claiming to represent half a million Welsh protesters.[13] The opposition against 'British' military usage of this site in Wales was summed up by Saunders Lewis when he wrote that the UK government was intent upon turning one of the 'essential homes of Welsh culture, idiom, and literature' into a place for promoting a barbaric method of warfare.[13]

On 8 September 1936 the building was arsoned, and Welsh nationalists Saunders Lewis, Lewis Valentine and D.J. Williams claimed responsibility.[13] The case was tried at Caernarfon, where the jury failed to reach a verdict. It was then sent to the Old Bailey in London, where the "Three" were convicted and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. On their release from Wormwood Scrubs they were greeted as heroes by a crowd of 15,000 people at a pavilion in Caernarfon.[13]

Broadcasting in Welsh and 1931 census[]

With the advent of broadcasting in Wales, Plaid Cymru protested against the lack of Welsh-language programmes in Wales and launched a campaign to withhold licence fees. Pressure was successful, and by the mid-1930s more Welsh-language programming was broadcast, with the formal establishment of a Welsh regional broadcasting channel by 1937.[14] However, no dedicated Welsh-language television channel would be established until 1982.

According to the 1931 census, out of a population of just over 2.5 million, the percentage of Welsh speakers in Wales had dropped to 36.8%, with Anglesey recording the highest concentration of speakers at 87.4%, followed by Cardigan at 87.1%, Merionethshire at 86.1%, and Carmarthen at 82.3%. Caernarfon listed 79.2%.[15] Radnorshire and Monmouthshire ranked lowest with a concentration of Welsh speakers less than 6% of the population.[15]

Welsh Courts Act 1942[]

Following the arrests of D.J Williams, Saunders Lewis and Lewis Valentine for the "tân yn llŷn" in 1936 all three were tried on charges of arson in Caernarfon crown court where their pleads were deemed invalid as they all pleaded in Welsh. Following the jury's indecision on the matter, it was decided that the case should be moved to the Old Bailey, causing outrage throughout Wales; this, along with the lack of status for the Welsh language in the legal system, sparked action. At Cardiff Eisteddfod in 1939 a petition was launched by Undeb Cymdeithasau Cymru (The union of Welsh societies) calling for recognition of the Welsh language in the courts. Their presentation of the petition to parliament in 1941 lead to the passing of the Welsh Courts Act 1942 and thus the validation of pleas in the Welsh language.

The flooding of Tryweryn 1956[]

In 1956, a private bill sponsored by Liverpool City Council was brought before the UK parliament to develop a water reservoir from the Tryweryn Valley, in Meirionnydd in Gwynedd. The development would include the flooding of Capel Celyn (Welsh: 'holly chapel'), a Welsh-speaking community of historic significance. Despite universal and bi-partisan objections by Welsh politicians (35 out of 36 Welsh MPs opposed the bill, and one abstained) the bill was passed in 1957. The events surrounding the flooding highlighted the status of the language in the 1950s and 1960s.

Tynged yr Iaith and the 1961 census[]

In 1962 Saunders Lewis gave a radio speech entitled Tynged yr iaith (The Fate of the Language) in which he predicted the extinction of the Welsh language unless direct action was taken. Lewis was responding to the 1961 census, which showed a decrease in the number of Welsh speakers from 36% in 1931 to 26% in 1961, out of a population of about 2.5 million.[16] Meirionnydd, Anglesey, Carmarthen, and Caernarfon averaged a 75% concentration of Welsh speakers, but the most significant decrease was in the counties of Glamorgan, Flint, and Pembroke.[17][18]

Lewis' intent was to motivate Plaid Cymru to take more direct action to promote the language; however it led to the formation of Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg (the Welsh Language Society) later that year at a Plaid Cymru summer school held in Pontardawe in Glamorgan.[19]

Welsh Language Act 1967[]

With concern for the Welsh language mounting in the 1960s, the Welsh Language Act 1967 was passed, giving some legal protection for the use of Welsh in official government business. The Act was based on the , published in 1965, which advocated equal validity for Welsh in speech and in written documents, both in the courts and in public administration in Wales. The Act did not include all the Hughes Parry report's recommendations. Prior to the Act, only the English language could be spoken at government and court proceedings due to the Act of Union 1536.

Hunger strike for S4C[]

Following the defeat of the Welsh Assembly "Yes Campaign" in 1979, and believing Welsh nationalism was "in a paralysis of helplessness", the UK Conservative Home Secretary announced in September 1979 that the government would not honour its pledge to establish a Welsh-language television channel,[20] much to widespread anger and resentment in Wales, wrote Dr. Davies.[20]

In early 1980 over two thousand members of Plaid Cymru pledged to go to prison rather than pay the television licence fees, and by that spring Gwynfor Evans announced his intention to go on hunger strike if a Welsh-language television channel was not established. In early September 1980, Evans addressed thousands at a gathering in which "passions ran high", according to Dr. Davies.[21] The government yielded by 17 September, and the Welsh Fourth Channel (S4C) was launched on 2 November 1982.

Welsh Language Act 1993[]

The Welsh Language Act 1993 put the Welsh language on an equal footing with the English language in Wales with regard to the public sector.

The Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542 had made English the only language of the law courts and other aspects of public administration in Wales. Although the Welsh Language Act 1967 had given some rights to use Welsh in court, the Welsh Language Act 1993 was the first to put Welsh on an equal basis with English in public life.

The Act set up the Welsh Language Board, answerable to the Secretary of State for Wales, with the duty to promote the use of Welsh and to ensure compliance with the other provisions. Additionally, the Act gave Welsh speakers the right to speak Welsh in court proceedings under all circumstances. The previous Act had only given limited protection to the use of Welsh in court proceedings. The Act obliges all organisations in the public sector providing services to the public in Wales to treat Welsh and English on an equal basis; however it does not compel private businesses to provide services in Welsh: that would require a further Language Act.

Some of the powers given to the Secretary of State for Wales under this Act were later devolved to the National Assembly for Wales (Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru), but others have been retained by Westminster.

21st century[]

In a speech at the 2000 National Eisteddfod at Llanelli, Cynog Dafis, Plaid Cymru AM, called for a new Welsh-language movement with greater powers to lobby for the Welsh language at the Assembly, UK, and EU levels.[22] Dafis felt the needs of the language were ignored during the first year of the Assembly, and that to ensure the dynamic growth of the Welsh language a properly resourced strategy was needed.[22] In his speech Dafis encouraged other Welsh-language advocacy groups to work more closely together to create a more favourable climate in which the use of Welsh was "attractive, exciting, a source of pride and a sign of strength".[22] Additionally, Dafis pointed towards efforts in areas such as Catalonia and the Basque country as successful examples to emulate.[22]

Lord Elis-Thomas, former Plaid Cymru president, disagreed with Dafis' assessment, however. At the Urdd Eisteddfod, Lord Elis-Thomas said that there was no need for another Welsh language act, citing that there was "enough goodwill to safeguard the language's future".[23] His comments prompted Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg and many others to call for his resignation as the Assembly's presiding officer.[23]

2001 census and second home controversy[]

In the 1991 census, the Welsh language stabilised at the 1981 level of 18.7%.

According to the 2001 census the number of Welsh speakers in Wales increased for the first time in over 100 years, with 20.8% in a population of over 2.9 million claiming fluency in Welsh.[24] Further, 28% of the population of Wales claimed to understand Welsh.[24] The census revealed that the increase was most significant in urban areas, such as Cardiff with an increase from 6.6% in 1991 to 10.9% in 2001, and Rhondda Cynon Taf with an increase from 9% in 1991 to 12.3% in 2001.[24] However, the number of Welsh speakers declined in Gwynedd from 72.1% in 1991 to 68.7%, and in Ceredigion from 59.1% in 1991 to 51.8%.[24] Ceredigion in particular experienced the greatest fluctuation with a 19.5% influx of new residents since 1991.[24]

The decline in Welsh speakers in Gwynedd and Ynys Môn may be attributable to non-Welsh-speaking people moving to North Wales, driving up property prices to levels that local Welsh speakers cannot afford, according to former Gwynedd county councillor of Plaid Cymru.

Glyn was commenting on a report underscoring the dilemma of rocketing house prices outstripping what locals could pay, with the report warning that "...traditional Welsh communities could die out..." as a consequence.[25]

Much of the rural Welsh property market was driven by buyers looking for second homes for use as holiday homes, or for retirement. Many buyers were drawn to Wales from England because of relatively inexpensive house prices in Wales as compared to house prices in England.[26][27] The rise in home prices outpaced the average earned income in Wales, and meant that many local people could not afford to purchase their first home or compete with second-home buyers.[27]

In 2001 nearly a third of all properties sold in Gwynedd were bought by buyers from out of the county, and some communities reported as many as a third of local homes used as holiday homes.[28][29] Holiday home owners spend less than six months of the year in the local community.

The issue of locals being priced out of the local housing market is common to many rural communities throughout the United Kingdom, but in Wales the added dimension of language further complicates the issue, as many new residents do not learn the Welsh language.[28][30][31][32]

Concern for the Welsh language under these pressures prompted Glyn to say "Once you have more than 50% of anybody living in a community that speaks a foreign language, then you lose your indigenous tongue almost immediately".[33]

Plaid Cymru had long advocated controls on second homes, and a 2001 task force headed by Dafydd Wigley recommended land should be allocated for affordable local housing, called for grants for locals to buy houses, and recommended that council tax on holiday homes should double, following similar measures in the Scottish Highlands.[29][30][33]

However the Welsh Labour-Liberal Democrat Assembly coalition rebuffed these proposals, with Assembly housing spokesman Peter Black stating that "we [cannot] frame our planning laws around the Welsh language", adding "Nor can we take punitive measures against second home owners in the way that they propose as these will have an impact on the value of the homes of local people".[33]

In contrast, by autumn 2001 the Exmoor National Park authority in England began to consider limiting second home ownership there, which was also driving up local housing prices by as much as 31%.[31] Elfyn Llwyd, Plaid Cymru's Parliamentary Group Leader, said that the issues in Exmoor National Park were the same as in Wales, however in Wales there is the added dimension of language and culture.[31]

Reflecting on the controversy Glyn's comments caused earlier in the year, Llwyd observed "What is interesting is of course it is fine for Exmoor to defend their community but in Wales when you try to say these things it is called racist..."[31]

Llwyd called on other parties to join in a debate to bring the Exmoor experience to Wales when he said "... I really do ask them and I plead with them to come around the table and talk about the Exmoor suggestion and see if we can now bring it into Wales".[31]

By spring 2002 both the Snowdonia National Park (Welsh: Parc Cenedlaethol Eryri) and Pembrokeshire Coast National Park (Welsh: Parc Cenedlaethol Arfordir Penfro) authorities began limiting second home ownership within the parks, following the example set by Exmoor.[34] According to planners in Snowdonia and the Pembrokeshire Coast, applicants for new homes must demonstrate a proven local need or that the applicant had strong links with the area.

It seems that the rise of Welsh nationalism rallied supporters of the language, and the establishment of Welsh television and radio found a mass audience which was encouraged in the retention of its Welsh. Perhaps most important of all, at the end of the 20th century it became compulsory for all schoolchildren to learn Welsh up to age 16, and this both reinforced the language in Welsh-speaking areas and reintroduced at least an elementary knowledge of it in areas which had become more or less wholly Anglophone. The decline in the percentage of people in Wales who can speak Welsh has now been halted, and there are even signs of a modest recovery. However, although Welsh is the daily language in many parts of Wales, English is universally understood. Further, overall figures may be misleading and it might be argued that the density of Welsh speakers (which, if high, leads to a thriving Welsh culture) is an equally important statistic. Put another way, were 50,000 additional Welsh speakers to be concentrated in areas where Welsh is spoken by at least 50% of the population, this would be much more important to the sustainability of the Welsh language than the same number dispersed in Cardiff, Newport and Swansea cities.

2011 census[]

In the 2011 census it was recorded that the proportion of people able to speak Welsh had dropped from 20.8% to 19%. Despite an increase in the overall size of the Welsh population this still meant that the number of Welsh speakers in Wales dropped from 582,000 in 2001 to 562,000 in 2011. However this figure was still much higher than 508,000 or 18.7% of people who said they could speak Welsh in the 1991 census.

2020-2021 Population Surveys[]

The April 2020 to March 2021 Annual Population Survey reported that 29.1% of people aged three and over were able to speak Welsh which equates to approximately 883,300 people.[35]

For October 2020 to 30 September 2021, the Annual Population Survey showed that 29.5% of people aged three or older were able to speak Welsh which equates to approximately 892,500 people. [36]

Recent attitudes toward the Welsh language[]

21st-century sentiment[]

Although recent progress in recognising the Welsh language, celebrating its use and making it equal to the English Language; prejudice still exists towards its use. Many still view it as a working class language. As the Welsh Language is closely tied with its Intangible cultural heritage, the Welsh as people have been targeted. Rod Liddle in The Spectator in 2010 stated that the Welsh are "miserable, seaweed munching, sheep-bothering pinch-faced hill-tribes".[37] In 2018, the same writer mocked the Welsh language in The Sunday Times after the renaming of the Severn crossing: "They would prefer it to be called something indecipherable with no real vowels, such as Ysgythysgymlngwchgwch Bryggy".[38] A Welsh Member of Parliament for Dwyfor Meirionnydd Liz Saville Roberts expressed these concerns that the Welsh are still seen as lower class citizens. She condemns Liddle's actions to BBC News, to go "out of his way, effectively, to mock Wales, he calls it poor compared to England and mocks that, and then goes on to mock our language".[39] However this is not the first time this opinion has been shared. Earlier in 1997, A.A. Gill expressed the same negative opinion of the Welsh, further describing them as "loquacious, dissemblers, immoral liars, stunted, bigoted, dark, ugly, pugnacious little trolls"[40]

This sentiment has also been held by TV presenters Anne Robinson and Jeremy Clarkson. Anne Robinson, referring to the Welsh asked "what are they for?" and that she "never did like them"[41] on the popular comedy programme Room 101 in 2001, at the time hosted by Paul Merton. The controversial ex BBC presenter Jeremy Clarkson is infamous for his discriminatory remarks against the Welsh people and their language. In 2011, Clarkson expressed his opinion in his column in The Sun that "We are fast approaching the time when the United Nations should start to think seriously about abolishing other languages. What's the point of Welsh for example? All it does is provide a silly maypole around which a bunch of hotheads can get all nationalistic".[42]

References[]

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Wales |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Art |

|

Notes[]

- ^ Koch, pp. 291–292.

- ^ a b c d Koch, p. 1757.

- ^ Pencader.

- ^ a b c John, Davies. "The 1536 Act of Union". BBC.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Davies, John (2007). A History of Wales. Penguin Adult.

- ^ J.W. Aitchison and H. Carter. Language, Economy and Society. The changing fortunes of the Welsh Language in the Twentieth Century. Cardiff. University of Wales Press. 2000.

- ^ "BBC Wales - History - Themes - Welsh language: The Welsh language in 19th century education".

- ^ See: R. Merfyn Jones, The North Wales Quarrymen, 1874–1922. Bethesda and Dinorwig were the largest slate quarries in the world and the largest industrial concerns in North Wales. Welsh was the working language of the quarries and of the North Wales Quarry Workers' Union. It was also the language of the quarry communities. Many of the leading Welsh literary figures of the late 19th and 20thC had their roots in these quarrying communities – e.g. Kate Roberts; T. H. Parry-Williams; R. Williams Parry; Thomas Parry; W J Gruffydd; Silyn Roberts; T Rowland Hughes; Ifor Williams; Gwenlyn Parry – as did a number of leading Welsh-speaking Labour MPs, including Cledwyn Hughes and Goronwy Roberts. Even in the industrial south east, the continuing strength of the Welsh language led the Independent Labour Party in 1911 to include Welsh language pages in the Merthyr Pioneer – edited at Keir Hardie's request by Thomas Evan Nicholas (Niclas y Glais).

- ^ Language in Wales, 1911 (official census report), Table I.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Davies 1994, 547

- ^ Davies 1994, 593

- ^ a b c d e Davies 1994, 592

- ^ Davies 1994, 590

- ^ a b County map 1931 BBC Wales History Extracted 12-03-07

- ^ BBCWales History extracted 12-03-07

- ^ 1961 BBCWales History extracted 12-03-07

- ^ 1931 BBCWales History extracted 12-03-07

- ^ Morgan, K O, Rebirth of a Nation, (1981), OUP

- ^ a b Davies 1994, 680

- ^ Davies 1994, 667

- ^ a b c d Call for new language movement Tuesday, 8 August 2000 extracted 27 Jan 2008

- ^ a b Elis-Thomas in language row Sunday, 4 June 2000 extracted 27 Jan 2008

- ^ a b c d e Census shows Welsh language rise Friday, 14 February 2003 extracted 12-04-07

- ^ 'Racist' remarks lost Plaid votes, BBC Wales, 3 September 2001

- ^ Property prices in England and Wales Wednesday, 8 August 2001, extracted 24 Jan 2008

- ^ a b House prices outpacing incomes Monday, 3 December 2001, extracted 24 Jan 2008

- ^ a b Apology over 'insults' to English, BBC Wales, 3 September 2001

- ^ a b UK: Wales Plaid calls for second home controls, BBC Wales, 17 November 1999

- ^ a b Double tax for holiday home owners Thursday, 16 December 1999, extracted 24 Jan 2008

- ^ a b c d e Controls on second homes reviewed Wednesday, 5 September 2001 extracted 24 Jan 2008

- ^ Gwynedd considers holiday home curb Tuesday, 9 April 2002, extracted 24 Jan 2008

- ^ a b c Plaid plan 'protects' rural areas, BBC Wales, 19 June 2001

- ^ Park to ban new holiday homes Wednesday, 6 March 2002 extracted 24 Jan 2008

- ^ "Welsh language data from the Annual Population Survey: April 2020 to March 2021". GOV.WALES. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ "Welsh language data from the Annual Population Survey: October 2020 to September 2021". GOV.WALES. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- ^ Liddle, Rodd (20 October 2010). "Sosban fach yn berwi ana tan". The Spectator. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Liddle, Rod. "Burglary is old hat for the Old Bill — so defending your home is murder". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ "Sunday Times' Rod Liddle 'mocks Wales' over Severn crossing renaming". BBC News. 8 April 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "BBC News | UK | Writer reported over 'ugly little trolls' Welsh jibe". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "TV watchdog clears Anne Robinson over Welsh jibes". The Guardian. 16 April 2001. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ WalesOnline (3 September 2011). "Jeremy Clarkson under fire over call for Welsh language to be abolished". WalesOnline. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

Bibliography[]

- Ballinger, John, The Bible in Wales: A Study in the History of the Welsh People, London, Henry Sotheran & Co., 1906.

- Davies, John, A History of Wales, Penguin, 1994, ISBN 0-14-014581-8, Page 547

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- History of the Welsh language