History of Latin

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2011) |

Latin is a member of the broad family of Italic languages. Its alphabet, the Latin alphabet, emerged from the Old Italic alphabets, which in turn were derived from the Etruscan, Greek and Phoenician scripts. Historical Latin came from the prehistoric language of the Latium region, specifically around the River Tiber, where Roman civilization first developed. How and when Latin came to be spoken by the Romans are questions that have long been debated. Various influences on Latin of Celtic dialects in northern Italy, the non-Indo-European Etruscan language in Central Italy, and the Greek in some Greek colonies of southern Italy have been detected, but when these influences entered the native Latin is not known for certain.

Surviving Latin literature consists almost entirely of Classical Latin in its broadest definition. It includes a polished and sometimes highly stylized literary language sometimes termed Golden Latin, which spans the 1st century BC and the early years of the 1st century AD. However, throughout the history of ancient Rome the spoken language differed in both grammar and vocabulary from that of literature, and is referred to as Vulgar Latin. In addition to Latin, the Greek language was often spoken by the well-educated elite, who studied it in school and acquired Greek tutors from among the influx of enslaved educated Greek prisoners of war, captured during the Roman conquest of Greece. In the eastern half of the Roman Empire, later referred to as the Byzantine Empire, the Greek Koine of Hellenism remained current among peasants and traders, while Latin was used for laws and administrative writings. It continued to influence the Vulgar Latin that would evolve into the Eastern Romance languages.

Origins[]

The name Latin derives from the Italic tribal group named Latini that settled around the 10th century BC in Latium, and the dialect spoken by these people.[1]

The Italic languages form a centum subfamily of the Indo-European language family. These include the Romance, Germanic, Celtic, and Hellenic languages, and a number of extinct ones.

Broadly speaking, in initial syllables the Indo-European simple vowels—(*a), *e, *i, *o, *u; short and long—are usually retained in Latin. The schwa indogermanicum (*ə) appears in Latin as a (cf. IE *pəter > L pater). Diphthongs are also preserved in Old Latin, but in Classical Latin some tend to become monophthongs (for example oi > ū or oe, and ei > ē > ī).[2] In non-initial syllables, there was more vowel reduction. The most extreme case occurs with short vowels in medial open syllables (i.e. short vowels followed by at most a single consonant, occurring neither in the first nor last syllable): All are reduced to a single vowel, which appears as i in most cases, but e (sometimes o) before r, and u before an l which is followed by o or u. In final syllables, short e and o are usually raised to i and u, respectively.

Consonants are generally more stable. However, the Indo-European voiced aspirates bh, dh, gh, gwh are not maintained, becoming f, f, h, f respectively at the beginning of a word, but usually b, d, g, v elsewhere. Non-initial dh becomes b next to r or u, e.g. *h₁rudh- "red" > rub-, e.g. rubeō "to be red"; *werdh- "word" > verbum. s between vowels becomes r, e.g. flōs "flower", gen. flōris; erō "I will be" vs. root es-; aurōra "dawn" < *ausōsā (cf. Germanic *aust- > English "east", Vedic Sanskrit uṣā́s "dawn"); soror "sister" < *sosor < *swezōr < *swésōr (cf. Old English sweostor "sister").

Of the original eight cases of Proto-Indo-European, Latin inherited six: nominative, vocative, accusative, genitive, dative, and ablative. The Indo-European locative survived in the declensions of some place names and a few common nouns, such as Roma "Rome" (locative Romae) and domus "home" (locative domī "at home"). Vestiges of the instrumental case may remain in adverbial forms ending in -ē.[3]

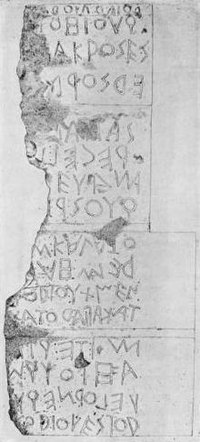

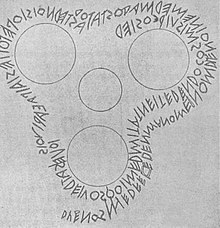

It is believed that the earliest surviving inscription is a seventh-century BC fibula known as the Praenestine fibula, which reads Manios med fhefhaked Numasioi "Manius made me for Numerius".[4]

Old Latin[]

Old Latin (also called Early Latin or Archaic Latin) refers to the period of Latin texts before the age of Classical Latin, extending from textual fragments that probably originated in the Roman monarchy to the written language of the late Roman republic about 75 BC. Almost all the writing of its earlier phases is inscriptional.

Some phonological characteristics of older Latin are the case endings -os and -om (later Latin -us and -um). In many locations, classical Latin turned intervocalic /s/ into /r/. This had implications for declension: early classical Latin, honos, honosis; Classical honor, honoris ("honor"). Some Latin texts preserve /s/ in this position, such as the Carmen Arvale's lases for lares.

Classical Latin[]

Classical Latin is the form of the Latin language used by the ancient Romans in Classical Latin literature. In the latest and narrowest philological model its use spanned the Golden Age of Latin literature—broadly the 1st century BC and the early 1st century AD—possibly extending to the Silver Age—broadly the 1st and 2nd centuries. It was a polished written literary language based on the refined spoken language of the upper classes. Classical Latin differs from Old Latin: the earliest inscriptional language and the earliest authors, such as Ennius, Plautus and others, in a number of ways; for example, the early -om and -os endings shifted into -um and -us ones, and some lexical differences also developed, such as the broadening of the meaning of words.[5] In the broadest and most ancient sense, the classical period includes the authors of Early Latin, the Golden Age and the Silver Age.

Golden Age[]

The golden age of Latin literature is a period consisting roughly of the time from 75 BC to AD 14, covering the end of the Roman Republic and the reign of Augustus Caesar. In the currently used philological model this period represents the peak of Latin literature. Since the earliest post-classical times the Latin of those authors has been an ideal norm of the best Latin, which other writers should follow.

Silver Age[]

In reference to Roman literature, the Silver age covers the first two centuries AD directly after the Golden age. Literature from the Silver Age is more embellished with mannerisms.

Late Latin[]

Late Latin is the administrative and literary language of Late Antiquity in the late Roman empire and states that succeeded the Western Roman Empire over the same range. By its broadest definition it is dated from about 200 AD to about 900 AD when it was replaced by written Romance languages. Opinion concerning whether it should be considered classical is divided. The authors of the period looked back to a classical period they believed should be imitated and yet their styles were often classical. According to the narrowest definitions, Late Latin did not exist and the authors of the times are to be considered medieval.

Vulgar Latin[]

Vulgar Latin (in Latin, sermo vulgaris) is a blanket term covering vernacular dialects of the Latin language spoken from earliest times in Italy until the latest dialects of the Western Roman Empire, diverging still further, evolved into the early Romance languages—whose writings began to appear about the 9th century.

This spoken Latin differed from the literary language of Classical Latin in its grammar and vocabulary. It is likely to have evolved over time, with some features not appearing until the late Empire. Other features are likely to have been in place much earlier. Because there are few phonetic transcriptions of the daily speech of these Latin speakers (to match, for example, the post-classical Appendix Probi) Vulgar Latin must be studied mainly by indirect methods.

Knowledge of Vulgar Latin comes from a variety of sources. First, the comparative method reconstructs items of the mother language from the attested Romance languages. Also, prescriptive grammar texts from the Late Latin period condemn some usages as errors, providing insight into how Latin was actually spoken. The solecisms and non-Classical usages occasionally found in late Latin texts also shed light on the spoken language. A windfall source lies in the chance finds of wax tablets such as those found at Vindolanda on Hadrian's Wall. The Roman cursive script was used on these tablets.

Romance languages[]

The Romance languages, a major branch of the Indo-European language family, comprise all languages that descended from Latin, the language of the Roman Empire. The Romance languages have more than 700 million native speakers worldwide, mainly in the Americas, Europe, and Africa, as well as in many smaller regions scattered through the world.

All Romance languages descend from Vulgar Latin, the language of soldiers, settlers, and slaves of the Roman Empire, which was substantially different from that of the Roman literati. Between 200 BC and AD 100, the expansion of the Empire and the administrative and educational policies of Rome made Vulgar Latin the dominant vernacular language over a wide area which stretched from the Iberian Peninsula to the west coast of the Black Sea. During the Empire's decline and after its collapse and fragmentation in the 5th century, Vulgar Latin began to evolve independently within each local area, and eventually diverged into dozens of distinct languages. The overseas empires established by Spain, Portugal and France after the 15th century then spread these languages to other continents—about two thirds of all Romance speakers are now outside Europe.

In spite of the multiple influences of pre-Roman languages and later invasions, the phonology, morphology, lexicon, and syntax of all Romance languages are predominantly derived from Vulgar Latin. As a result, the group shares a number of linguistic features that set it apart from other Indo-European branches.

Ecclesiastical Latin[]

Ecclesiastical Latin (sometimes called Church Latin) is a broad and analogous term referring to the Latin language as used in documents of the Roman Catholic Church, its liturgies (mainly in past times) and during some periods the preaching of its ministers. Ecclesiastical Latin is not a single style: the term merely means the language promulgated at any time by the church. In terms of stylistic periods, it belongs to Late Latin in the Late Latin period, Medieval Latin in the Medieval Period, and so on through to the present. One may say that, starting from the church's decision in the early Late Latin period to use a simple and unornamented language that would be comprehensible to ordinary Latin speakers and yet still be elegant and correct, church Latin is usually a discernible substyle within the major style of the period. Its authors in the New Latin period are typically paradigmatic of the best Latin and that is true in contemporary times. The decline in its use within the last 100 years has been a matter of regret to some, who have formed organizations inside and outside the church to support its use and to use it.

Medieval Latin[]

Medieval Latin, the literary and administrative Latin used in the Middle Ages, exhibits much variation between individual authors, mainly due to poor communications in those times between different regions. The individuality is characterised by a different range of solecisms and by the borrowing of different words from Vulgar Latin or from local vernaculars. Some styles show features intermediate between Latin and Romance languages; others are closer to classical Latin. The stylistic variations came to an end with the rise of nation states and new empires in the Renaissance period, and the authority of early universities imposing a new style: Renaissance Latin.

Renaissance Latin[]

Renaissance Latin is a name given to the Latin written during the European Renaissance in the 14th-16th centuries, particularly distinguished by the distinctive Latin style developed by the humanist movement.

Ad fontes was the general cry of the humanists, and as such their Latin style sought to purge Latin of the medieval Latin vocabulary and stylistic accretions that it had acquired in the centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire. They looked to Golden Age Latin literature, and especially to Cicero in prose and Virgil in poetry, as the arbiters of Latin style. They abandoned the use of the sequence and other accentual forms of meter, and sought instead to revive the Greek formats that were used in Latin poetry during the Roman period. The humanists condemned the large body of medieval Latin literature as "gothic"—for them, a term of abuse—and believed instead that only ancient Latin from the Roman period was "real Latin".

The humanists also sought to purge written Latin of medieval developments in its orthography. They insisted, for example, that ae be written out in full wherever it occurred in classical Latin; medieval scribes often wrote e instead of ae. They were much more zealous than medieval Latin writers in distinguishing t from c: because the effects of palatalization made them homophones, medieval scribes often wrote, for example, eciam for etiam. Their reforms even affected handwriting: humanists usually wrote Latin in a script derived from Carolingian minuscule, the ultimate ancestor of most contemporary lower-case typefaces, avoiding the black-letter scripts used in the Middle Ages. Erasmus even proposed that the then-traditional pronunciations of Latin be abolished in favour of his reconstructed version of classical Latin pronunciation.

The humanist plan to remake Latin was largely successful, at least in education. Schools now taught the humanistic spellings, and encouraged the study of the texts selected by the humanists, largely to the exclusion of later Latin literature. On the other hand, while humanist Latin was an elegant literary language, it became much harder to write books about law, medicine, science or contemporary politics in Latin while observing all of the humanists' norms of vocabulary purging and classical usage. Because humanist Latin lacked precise vocabulary to deal with modern issues, their reforms accelerated the transformation of Latin from a working language to an object of antiquarian study. Their attempts at literary work, especially poetry, often have a strong element of pastiche.

New Latin[]

After the medieval era, Latin was revived in original, scholarly, and scientific works between c. 1375 and c. 1900. The result language is called New Latin. Modern scholarly and technical nomenclature, such as in zoological and botanical taxonomy and international scientific vocabulary, draws extensively from New Latin vocabulary. In such use, New Latin is subject to new word formation. As a language for full expression in prose or poetry, however, it is often distinguished from its successor, Contemporary Latin.

Classicists use the term "Neo-Latin" to describe the use of Latin after the Renaissance as a result of renewed interest in classical civilization in the 14th and 15th centuries.[6]

Contemporary Latin[]

Contemporary Latin is the form of the Latin language used since the end of the 19th century. Various kinds of contemporary Latin can be distinguished, including the use of single words in taxonomy, and the fuller ecclesiastical use in the Catholic Church

As a relic of the great importance of New Latin as the formerly dominant international lingua franca down to the 19th century in a great number of fields, Latin is still present in words or phrases used in many languages around the world, and some minor communities use Latin in their speech.

Phonological changes[]

Vowels[]

Proto-Italic inherited all ten of the early post-Proto-Indo-European simple vowels (i.e. at a time when laryngeals had colored and often lengthened adjacent vowels and then disappeared in many circumstances): *a, *e, *i, *o, *u, *ā, *ē, *ī, *ō, *ū. It also inherited all of the post-PIE diphthongs except for *eu, which became *ou. Proto-Italic and Old Latin had a stress accent on the first syllable of a word, and this caused steady reduction and eventual deletion of many short vowels in non-initial syllables while affecting initial syllables much less. Long vowels were largely unaffected in general except in final syllables, where they had a tendency to shorten.

| Initial | Medial | Final | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proto-Italic | +r | +l pinguis | +labial

(/p, b, f, m/) |

+v (/w/) | +other | +one consonant | +cluster | Absolutely final | ||||

| one consonant | cluster | s | m, n | other | ||||||||

| a | a | e[a] | o > u[b] | ʏ

(sonus medius)[c] |

u | e > i[d] | e[e] | i | e | i | e | e |

| e | e | o > u[f] | ||||||||||

| i | i | i? | i[g] | |||||||||

| o | o | o > u[h] | o[i] | u | ||||||||

| u | u | u[j] | u[k] | |||||||||

| ā | ā | a | a, ā | |||||||||

| ē | ē | e | ē? | |||||||||

| ī | ī | i | ī? | |||||||||

| ō | ō | o | ō | |||||||||

| ū | ū | u | ū? | |||||||||

| ai | ae | ī | ||||||||||

| au | au | ū | ||||||||||

| ei | ī | |||||||||||

| oi | ū, oe | ū | ī | |||||||||

| ou | ū | |||||||||||

Notes:

- ^ Example: imberbis (from in + barba)

- ^ Example: exsultare (from ex + saltare)

- ^ Examples: documentum, optimus, lacrima (also spelled docimentum, optumus, lacruma)

- ^ Examples: inficere (from in + facere), oppidum (from ob + pedum, borrowed from Gr. πέδον)

- ^ Examples: infectus (from in + factus), ineptus (from in + aptus), exspectare (from ex + spectare)

- ^ Examples: occultus (from ob + cel(a)tus), multus (from PIE *mel-)

- ^ Example: invictus (from in + victus)

- ^ Example: cultus (participle of colō)

- ^ Example: adoptare (from ad + optare)

- ^ Example: exculpare (from ex + culpare)

- ^ Example: eruptus (from e + ruptus)

Note: For the following examples, it helps to keep in mind the normal correspondences between PIE and certain other languages:

| (post-)PIE | Ancient Greek | Old English | Gothic | Sanskrit | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *i | i | i | i, aí /ɛ/ | i | |

| *e | e | e | i, aí /ɛ/ | a | |

| *a | a | a | a | a | |

| *o | o | a | a | a | |

| *u | u | u, o | u, aú /ɔ/ | u | |

| *ī | ī | ī | ei /ī/ | ī | |

| *ē | ē | ā | ē | ā | |

| *ā | ē (Attic); ā (Doric, etc.) |

ō | ō | ā | |

| *ō | ō | ō | ō | ā | |

| *ū | ū | ū | ū | ū | |

| *ai | ai | ā | ái | ē | |

| *au | au | ēa | áu | ō | |

| *ei | ei | ī | ei /ī/ | ē | |

| *eu | eu | ēo | iu | ō | |

| *oi | oi | ā | ái | ē | |

| *ou | ou | ēa | áu | ō | |

| *p | p | f | f; b | p | b in Gothic by Verner's law |

| *t | t | þ/ð; d | þ; d | t | þ and ð are different graphs for the same sound; d in the Germanic languages by Verner's law |

| *ḱ | k | h; g | h; g | ś | g in the Germanic languages by Verner's law |

| *k | k; c (+ PIE e/i) | ||||

| *kʷ | p; t (+ e/i) | hw, h; g, w | ƕ /hʷ/; g, w, gw | g, w, gw in the Germanic languages by Verner's law | |

| *b | b | p | p | b | |

| *d | d | t | t | d | |

| *ǵ | g | k | k | j | |

| *g | g; j (+ PIE e/i) | ||||

| *gʷ | b; d (+ i) | q, c | q | ||

| *bʰ | ph; p | b | b | bh; b | Greek p, Sanskrit b before any aspirated consonant (Grassmann's law) |

| *dʰ | th; t | d | d | dh; d | Greek t, Sanskrit d before any aspirated consonant |

| *ǵʰ | kh; k | g | g | h; j | Greek k, Sanskrit j before any aspirated consonant |

| *gʰ | gh; g h; j (+ PIE e/i) |

Greek k, Sanskrit g, j before any aspirated consonant | |||

| *gʷʰ | ph; p th; t (+ e/i) |

b (word-initially); g, w |

b (word-initially); g, w, gw |

Greek p, t, Sanskrit g, j before any aspirated consonant | |

| *s | h (word-initially); s, - | s; r | s; z | s, ṣ | r, z in Germanic by Verner's law; Sanskrit ṣ by Ruki sound law |

| *y | h, z (word-initially); - | g(e) /j/ | j /j/ | y | |

| *w | - | w | w | v |

Pure vowels[]

Initial syllables[]

In initial syllables, Latin generally preserves all of the simple vowels of Proto-Italic (see above):

- PIE *h₂eǵros "field" > *agros > ager, gen. agrī (Greek agrós, English acre, Sanskrit ájra-)

- PIE *kápros "he-goat" > *kapros > caper "he-goat", gen. caprī (Greek kápros "boar", Old English hæfer "he-goat", Sanskrit kápṛth "penis")

- PIE *swéḱs "six", septḿ̥ "seven" > *seks, *septem > sex, septem (Greek heks, heptá, Lithuanian šešì, septynì, Sanskrit ṣáṣ, saptá-)

- PIE *kʷís > *kʷis > quis "who?" (Greek tís,[8] Avestan čiš, Sanskrit kís)

- PIE *kʷód > *kʷod > quod "what, that" (relative) (Old English hwæt "what", Sanskrit kád)

- PIE *oḱtṓ "eight" > *oktō > octō (Greek oktṓ, Irish ocht, Sanskrit aṣṭā́)

- PIE *nókʷts "night" > *noks > nox, gen. noctis (Greek nuks < *nokʷs, Sanskrit nákt- < *nákts, Lithuanian naktìs)

- PIE *yugóm "yoke" > *jugom > iugum (Greek zugón, Gothic juk, Sanskrit yugá-)

- PIE *méh₂tēr "mother" > *mātēr > māter (Doric Greek mā́tēr, Old Irish máthir, Sanskrit mā́tṛ)

- PIE *sweh₂dús "pleasing, tasty" > *swādus > *swādwis (remade into i-stem) > suāvis (Doric Greek hādús, English sweet, Sanskrit svādú-)

- PIE *sēmi- "half" > *sēmi- > sēmi- (Greek hēmi-, Old English sām-, Sanskrit sāmí)

- PIE *ǵneh₃tós "known" > *gnōtos > nōtus (i-gnōtus "unknown"; Welsh gnawd "customary", Sanskrit jñātá-; Greek gnōtós[9])

- PIE *múh₂s "mouse" > *mūs > mūs (Old English mūs, Greek mûs, Sanskrit mū́ṣ)

- PIE *gʷih₃wós "alive" > *gʷīwos > vīvus (Old English cwic, English quick, Greek bíos "life", Sanskrit jīvá-, Slavic živъ)

Short vowel changes in initial syllables:

- *swe- > so-:

- *swezōr > soror, gen. sorōris "sister"

- *swepnos > *swepnos > somnus "sleep"

- *we- > wo- before labial consonants or velarized l [ɫ] (l pinguis; i.e. an l not followed by i, ī or l):

- *welō "I want" > volō (vs. velle "to want" before l exīlis)

- *wemō "I vomit" > vomō (Greek eméō, Sanskrit vámiti)

- e > i before [ŋ] (spelled n before a velar, or g before n):

- PIE *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂s > *denɣwā > Old Latin dingua > lingua "tongue" (l- from lingō "to lick")

- PIE *deḱnós > *degnos > dignus "worthy"

There are numerous examples where PIE *o appears to result in Latin a instead of expected o, mostly next to labial or labializing consonants. A group of cases showing *-ow- > *-aw- > -av- (before stress), *-ōw- > *-āw- > -āv- is known as Thurneysen-Havet's law:[10] examples include PIE *lowh₃ṓ > *lawō > lavō 'I wash'; PIE *oḱtṓwos > *oktāwos > octāvus 'eighth' (but octō 'eight'). Other cases remain more disputed, such as mare 'sea', in contrast to Irish muir, Welsh môr (Proto-Celtic *mori) < PIE *móri; lacus 'lake', in contrast to Irish loch < PIE *lókus. De Vaan (2008: 8) suggests a general shift *o > a in open syllables when preceded by any of *b, *m; *kʷ, *w; *l. Vine (2011)[11] disputes the cases with *moCV, but proposes inversely that *mo- > ma- when followed by r plus a velar (k or g).

Medial syllables[]

In non-initial syllables, there was more vowel reduction of short vowels. The most extreme case occurs with short vowels in medial syllables (i.e. short vowels in a syllable that is neither the first nor the last), where all five vowels usually merge into a single vowel:

1. They merge into e before r (sometimes original o is unaffected)

- *en-armis > inermis "unarmed" (vs. arma "arms")

- Latin-Faliscan *pe-par-ai "I gave birth" > peperī (vs. pariō "I give birth")

- *kom-gesō > congerō "to collect" (vs. gerō "to do, carry out")

- *kinis-es "ash" (gen.sg.) > cineris (vs. nom.sg. cinis)

- *Falisiōi > Faleriī "Falerii (major town of the Faliscans)" (vs. Faliscus "Faliscan")

- Latin-Faliscan Numasiōi (Praeneste fibula) > Numeriō "Numerius"

- *-foro- "carrying" (cf. Greek -phóros) > -fero-, e.g. furcifer "gallows bird"

- PIE *swéḱuros "father-in-law" > *swekuros > Old Latin *soceros > socer, gen. socerī

2. They become Old Latin o > u before l pinguis, i.e., an l not followed by i, ī, or l:

- *en-saltō "to leap upon" > īnsoltō (with lengthening before ns) > īnsultō (vs. saltō "I leap")

- *ad-alēskō "to grow up" > adolēscō > adulēscō (vs. alō "I nourish")

- *ob-kelō "to conceal" > occulō (vs. celō "I hide")

- Greek Sikelós "a Sicilian" > *Sikolos > Siculus (vs. Sicilia "Sicily")

- te-tol-ai > tetulī "I carried" (formerly l pinguis here because of the original final -ai)

- kom-solō "deliberate" > cōnsulō

- PIE *-kl̥d-to- "beaten" > *-kolsso-[12] > perculsus "beaten down"

3. But they remain o before l pinguis when immediately following a vowel:

- Latin-Faliscan *fili-olos > filiolus "little son"

- Similarly, alveolus "trough"

4. Before /w/ the result is always u, in which case the /w/ is not written:

- *eks-lawō "I wash away" > ēluō

- *mon-i-wai "I warned" > monuī

- *tris-diw-om "period of three days" > trīduom > trīduum

- *dē nowōd "anew" > dēnuō

5. They become i before one consonant other than r or l pinguis:

- *wre-fakjō "to remake" > *refakiō > reficiō (vs. faciō "I do, make")

- Latin-Faliscan *ke-kad-ai "I fell" > cecidī (vs. cadō "I fall")

- *ad-tenējō > attineō "to concern" (vs. teneō "I hold")

- *kom-regō > corrigō "to set right, correct" (vs. regō "I rule; straighten")

- Greek Sikelía "Sicily" > Sicilia (vs. Siculus "a Sicilian")

- PIE *me-món-h₂e (perfect) "thought, pondered" > Latin-Faliscan *me-mon-ai > meminī "I remember"

- *kom-itājō "accompany" > comitō

- *nowotāts "newness" > novitās

- *kornu-kan- "trumpeter" > cornicen

- *kaput-es "head" (gen. sg.) > capitis (vs. nom.sg. caput)

6. But they sometimes become e before one consonant other than r or l pinguis, when immediately following a vowel:

- *sokiotāts "fellowship" > societās

- *wariogājesi "to make diverse" > variegāre

- But: *tībia-kan- "flute-player" > *tībiikan- > tībīcen

- But: *medio-diēs "midday" > *meriodiēs (dissimilative rhotacism) > *meriidiēs > merīdiēs "noon; south"

7. Variation between i and (often earlier) u is common before a single labial consonant (p, b, f, m), underlyingly the sonus medius vowel:

- From the root *-kap- "grab, catch":

- occupō "seize" vs. occipiō "begin"

- From the related noun *-kaps "catcher": prīnceps "chief" (lit. "seizer of the first (position)"), gen. prīncipis, vs. auceps "bird catcher", gen. aucupis

- *man-kapiom > mancupium "purchase", later mancipium

- *sub-rapuit > surrupuit "filches", later surripuit

- *mag-is-emos > maxumus "biggest", later maximus; similarly proxumus "nearest", optumus "best" vs. later proximus, optimus

- *pot-s-omos > possumus "we can"; *vel-omos > volumus "we want"; but *leg-omos > legimus "we gather", and all other such verbs (-umus is isolated in sumus, possumus and volumus)

Medially before two consonants, when the first is not r or l pinguis, the vowels do not merge to the same degree:

1. Original a, e and u merge into e:

- Greek tálanton > *talantom > talentum

- *sub-raptos "filched" > surreptus (vs. raptus "seized")

- *wre-faktos "remade" > refectus (cf. factus "made")

- *ad-tentos > attentus "concerned" (cf. tentus "held", attineō "to concern")

2. But original i is unaffected:

- *wre-likʷtos "left (behind)" > relictus

3. And original o raises to u:

- *legontor "they gather" > leguntur

- *ejontes "going" (gen. sg.) > euntis

- rōbos-to- > rōbustus "oaken" (cf. rōbur "oak" < *rōbos)

Syncope[]

Exon's Law dictates that if there are two light medial syllables in a row (schematically, σσ̆σ̆σ, where σ = syllable and σ̆ = light syllable, where "light" means a short vowel followed by only a single consonant), the first syllable syncopates (i.e. the vowel is deleted):

- *deksiteros "right (hand)" > dexterus (cf. Greek deksiterós)

- *wre-peparai > repperī "I found" (cf. peperī "I gave birth" < *peparai)

- *prīsmo-kapes > prīncipis "prince" gen. sg. (nom. sg. prīnceps < *prīsmo-kaps by analogy)

- *mag-is-emos > maximus "biggest" (cf. magis "more")

Syncopation tends to occur after r and l in all non-initial syllables, sometimes even in initial syllables.[13]

- *feret "he carries" > fert

- *agros "field" > *agr̩s > *agers > *agerr > ager

- *imbris "rainstorm" > *imbers > imber

- *tris "three times" > *tr̩s > *ters > Old Latin terr > ter

- *faklitāts > facultās

Sometimes early syncope causes apparent violations of Exon's Law:

- kosolinos "of hazel" > *kozolnos (not **koslinos) > *korolnos > *korulnos (o > u before l pinguis, see above) > colurnus (metathesis)

Syncope of -i- also occurred in -ndis, -ntis and -rtis.[13] -nts then became -ns with lengthening of the preceding vowel, while -rts was simplified to -rs without lengthening.

- *montis "hill" > *monts > mōns

- *gentis "tribe" > *gents > gēns

- *frondis "leaf" > *fronts > frōns

- *partis "part" > *parts > pars

Final syllables[]

In final syllables of polysyllabic words before a final consonant or cluster, short a, e, i merge into either e or i depending on the following consonant, and short o, u merge into u.

1. Short a, e, i merge into i before a single non-nasal consonant:

- Proto-Italic *wrededas, *wrededat > reddis, reddit "you return, he returns"

- PIE thematic 2nd/3rd sg. *-esi, *-eti > PI *-es, *-et > -is, -it (e.g. legis, legit "you gather, he gathers")

- i-stem nom. sg. *-is > -is

2. Short a, e, i merge into e before a cluster or a single nasal consonant:

- *prīsmo-kaps > prīnceps "first, chief" (cf. capiō "to take")

- *kornu-kan-(?s) > cornicen "trumpeter" (cf. canō "to sing")

- *mīlets > mīles "soldier"

- *in-art-is > iners "unskilled" (cf. ars "skill")

- *septḿ̥ > septem "seven"

- i-stem acc. sg. *-im > -em

3. Short o, u merge into u:

- o-stem nominative *-os > Old Latin -os > -us

- o-stem accusative *-om > Old Latin -om > -um

- PIE thematic 3rd pl. *-onti > *-ont > -unt

- PIE *yekʷr̥ > *jekʷor > iecur "liver"

- PIE thematic 3rd sg. mediopassive *-etor > -itur

- *kaput > caput "head"

4. All short vowels apparently merge into -e in absolute final position.[dubious ]

- PIE *móri > PI *mari > mare "sea" (cf. plural maria)

- Proto-Italic *kʷenkʷe > quīnque "five"

- 2nd sg. passive -ezo, -āzo > -ere, -āre

- PI s-stem verbal nouns in *-zi > infinitives in -re

- But: u-stem neuter nom./acc. sg. *-u > -ū, apparently by analogy with gen. sg. -ūs, dat./abl. sg. -ū (it is not known if this change occurred already in Proto-Italic)

Long vowels in final syllables shorten before most consonants (but not final s), yielding apparent exceptions to the above rules:

- Proto-Italic *amāt > amat "he/she loves" (cf. passive amātur)

- Proto-Italic *amānt > amant "they love"

- a-stem acc. sg. *-ām > -am

- PIE thematic 1st sg. mediopassive *-ōr > -or

- *swesōr > soror "sister" (cf. gen. sorōris)

Absolutely final long vowels are apparently maintained with the exception of ā, which is shortened in the 1st declension nominative singular and the neuter plural ending (both < PIE *-eh₂) but maintained in the 1st conjugation 2nd sg. imperative (< PIE *-eh₂-yé).

Diphthongs[]

Initial syllables[]

Proto-Italic maintained all PIE diphthongs except for the change *eu > *ou. The Proto-Italic diphthongs tend to remain into Old Latin but generally reduce to pure long vowels by Classical Latin.

1. PIE *ei > Old Latin ei > ẹ̄, a vowel higher than ē < PIE *ē. This then developed to ī normally, but to ē before v:

- PIE *deiḱ- "point (out)" > Old Latin deicō > dīcō "to say"

- PIE *bʰeydʰ- "be persuaded, be confident" > *feiðe- > fīdō "to trust"

- PIE *deiwós "god, deity" > Very Old Latin deiuos (Duenos inscription) > dẹ̄vos > deus

- But nominative plural *deivoi > *deivei > *dẹ̄vẹ̄ > dīvī > diī; vocative singular *deive > *dẹ̄ve > dīve

2. PIE *eu, *ou > Proto-Italic *ou > Old Latin ou > ọ̄ (higher than ō < PIE *ō) > ū:

- PIE *(H)yeug- "join" > *youg-s-mn̥-to- > Old Latin iouxmentom "pack horse" > iūmentum

- PIE *louk-s-neh₂ > *louksnā > Old Latin losna (i.e. lọ̄sna) > lūna "moon" (cf. Old Prussian lauxnos "stars", Avestan raoχšnā "lantern")

- PIE *deuk- > *douk-e- > Old Latin doucō > dūcō "lead"

3. PIE (*h₂ei >) *ai > ae:

- PIE *kh₂ei-ko- > *kaiko- > caecus "blind" (cf. Old Irish cáech /kaiχ/ "blind", Gothic háihs "one-eyed", Sanskrit kekara- "squinting")

4. PIE (*h₂eu >) *au > au:

- PIE *h₂eug- > *augeje/o > augeō "to increase" (cf. Greek aúksō, Gothic áukan, Lithuanian áugti)

5. PIE *oi > Old Latin oi, oe > ū (occasionally preserved as oe):

- PIE *h₁oi-nos > Old Latin oinos > oenus > ūnus "one"

- Greek Phoiniks > Pūnicus "Phoenician"

- But: PIE *bʰoidʰ- > *foiðo- > foedus "treaty" (cf. fīdō above)

Medial syllables[]

All diphthongs in medial syllables become ī or ū.

1. (Post-)PIE *ei > ī, just as in initial syllables:

- *en-deik-ō > indīcō "to point out" (cf. dīcō "to say")

2. (Post-)PIE *oi > ū, just as in initial syllables:

- PIE *n̥-poini "with impunity" > impūne (cf. poena "punishment").

3. (Post-)PIE *eu, *ou > Proto-Italic *ou > ū, just as in initial syllables:

- *en-deuk-ō > *indoucō > indūcō "to draw over, cover" (cf. dūcō "to lead")

4. Post-PIE *ai > Old Latin ei > ī:

- *ke-kaid-ai "I cut", perf. > cecīdī (cf. caedō "I cut", pres.)

- *en-kaid-ō "cut into" > incīdō (cf. caedō "cut")

- Early Greek (or from an earlier source) *elaíwā "olive" > olīva

5. Post-PIE *au > ū (rarely oe):

- *en-klaud-ō "enclose" > inclūdō (cf. claudō "close")

- *ad-kauss-ō "accuse" > accūsō (cf. causa "cause")

- *ob-aud-iō "obey" > oboediō (cf. audiō "hear")

Final syllables[]

Mostly like medial syllables:

- *-ei > ī: PIE *meh₂tr-ei "to mother" > mātrī

- *-ai > ī in multisyllabic words: Latin-Faliscan peparai "I brought forth" > peperī

- *-eu/ou- > ū: post-PIE manous "hand", gen. sg. > manūs

Different from medial syllables:

- -oi > Old Latin -ei > ī (not ū): PIE o-stem plural *-oi > -ī (cf. Greek -oi);

- -oi > ī also in monosyllables: PIE kʷoi "who" > quī

- -ai > ae in monosyllables: PIE *prh₂ei "before" > prae (cf. Greek paraí)

Syllabic resonants and laryngeals[]

The PIE syllabic resonants *m̥, *n̥, *r̥, *l̥ generally become em, en, or, ol (cf. Greek am/a, an/a, ar/ra, al/la; Germanic um, un, ur, ul; Sanskrit am/a, an/a, r̥, r̥; Lithuanian im̃, iñ, ir̃, il̃):

- PIE *déḱm̥(t) "ten" > decem (cf. Irish deich, Greek deka, Gothic taíhun /tɛhun/)

- PIE *(d)ḱm̥tóm "hundred" > centum (cf. Welsh cant, Gothic hund, Lithuanian šim̃tas, Sanskrit śatám)

- PIE *n̥- "not" > OL en- > in- (cf. Greek a-/an-, English un-, Sanskrit a-, an-)

- PIE *tn̥tós "stretched" > tentus (cf. Greek tatós, Sanskrit tatá-)

- PIE *ḱr̥d- "heart" > *cord > cor (cf. Greek kēr, English heart, Lithuanian širdìs, Sanskrit hṛd-)

- PIE *ml̥dús "soft" > *moldus > *moldwis (remade as i-stem) > *molwis > mollis (cf. Irish meldach "pleasing", English mild, Czech mladý)

The laryngeals *h₁, *h₂, *h₃ appear in Latin as a when between consonants, as in most languages (but Greek e/a/o respectively, Sanskrit i):

- PIE *dʰh₁-tós "put" > L factus, with /k/ of disputed etymology (cf. Greek thetós, Sanskrit hitá- < *dhitá-)

- PIE *ph₂tḗr "father" > L pater (cf. Greek patḗr, Sanskrit pitṛ́, English father)

- PIE *dh₃-tós "given" > L datus (cf. Greek dotós, Sanskrit ditá-)

A sequence of syllabic resonant + laryngeal, when before a consonant, produced mā, nā, rā, lā (as also in Celtic, cf. Greek nē/nā/nō, rē/rā/rō, etc. depending on the laryngeal; Germanic um, un, ur, ul; Sanskrit ā, ā, īr/ūr, īr/ūr; Lithuanian ím, ín, ír, íl):

- PIE *ǵr̥h₂-nom "grain" > grānum (cf. Old Irish grán, English corn, Lithuanian žìrnis "pea", jīrṇá- "old, worn out")

- PIE *h₂wl̥h₁-neh₂ "wool" > *wlānā > lāna (cf. Welsh gwlân, Gothic wulla, Greek lēnos, Lithuanian vìlna, Sanskrit ū́rṇa-)

- PIE *ǵn̥h₁-tos "born" > gnātus "son", nātus "born" (participle) (cf. Middle Welsh gnawt "relative", Greek dió-gnētos "Zeus' offspring", Sanskrit jātá-, English kind, kin)

Consonants[]

Aspirates[]

The Indo-European voiced aspirates bʰ, dʰ, gʰ, gʷʰ, which were probably breathy voiced stops, first devoiced in initial position (fortition), then fricatized in all positions, producing pairs of voiceless/voiced fricatives in Proto-Italic: f ~ β, θ ~ ð, χ ~ ɣ, χʷ ~ ɣʷ respectively.[14] The fricatives were voiceless in initial position. However, between vowels and other voiced sounds, there are indications—in particular, their evolution in Latin—that the sounds were actually voiced. Likewise, Proto-Italic /s/ apparently had a voiced allophone [z] in the same position.

In all Italic languages, the word-initial voiceless fricatives f, θ, and χʷ all merged to f, whereas χ debuccalized to h (except before a liquid where it became g); thus, in Latin, the normal outcome of initial PIE bʰ, dʰ, gʰ, gʷʰ is f, f, h, f, respectively. Examples:

- PIE *bʰréh₂tēr "brother" > *bʰrā́tēr > frāter (cf. Old Irish bráthair, Sanskrit bhrā́tar-, Greek phrā́tēr "member of a phratry")

- PIE *bʰér-e- "carry" > ferō (cf. Old Irish beirid "bears", English bear, Sanskrit bhárati)

- PIE *dʰwṓr "door" > θwor- > *forā > forēs (pl.) "door(s)" (cf. Welsh dôr, Greek thurā, Sanskrit dvā́ra- (pl.))

- PIE *dʰeh₁- "put, place" > *dʰh₁-k- > *θaki- > faciō "do, make" (cf. Welsh dodi, English do, Greek títhēmi "I put", Sanskrit dádhāti he puts")

- PIE *gʰabʰ- "seize, take" > *χaβ-ē- > habeō "have" (cf. Old Irish gaibid "takes", Old English gifan "to give", Polish gabać "to seize")

- PIE *ǵʰh₂ens "goose" > *χans- > (h)ānser (cf. Old Irish géiss "swan", German Gans, Greek khḗn, Sanskrit haṃsá-)

- PIE *ǵʰaidos "goat" > *χaidos > haedus "kid" (cf. Old English gāt "goat", Polish zając "hare", Sanskrit háyas "horse")

- PIE *gʷʰerm- "warm" > *χʷormo- > formus (cf. Old Prussian gorme "heat", Greek thermós, Sanskrit gharmá- "heat")

- PIE *gʷʰen-dʰ- "to strike, kill" > *χʷ(e)nð- > fendō (cf. Welsh gwanu "to stab", Old High German gundo "battle", Sanskrit hánti "(he) strikes, kills", -ghna "killer (used in compounds)" )

Word-internal *-bʰ-, *-dʰ-, *-gʰ-, *-gʷʰ- evolved into Proto-Italic β, ð, ɣ, ɣʷ. In Osco-Umbrian, the same type of merger occurred as that affecting voiceless fricatives, with β, ð, and ɣʷ merging to β. In Latin, this did not happen, and instead the fricatives defricatized, giving b, d ~ b, g ~ h, g ~ v ~ gu.

*-bʰ- is the simplest case, consistently becoming b.

- PIE *bʰébʰrus "beaver" > *feβro > Old Latin feber > fiber

*-dʰ- usually becomes d, but becomes b next to r or u, or before l.

- PIE *bʰeidʰ- "be persuaded" > *feiðe > fīdō "I trust" (cf. Old English bīdan "to wait", Greek peíthō "I trust")

- PIE *medʰi-o- "middle" > *meðio- > medius (cf. Old Irish mide, Gothic midjis, Sanskrit mádhya-)

- PIE *h₁rudʰ-ró- "red" > *ruðro- > ruber (cf. Old Russian rodrŭ, Greek eruthrós, Sanskrit rudhirá-)

- PIE *werh₁-dʰh₁-o- "word" > *werðo- > verbum (cf. English word, Lithuanian var̃das)

- PIE *krei(H)-dʰrom "sieve, sifter" > *kreiðrom > crībrum "sieve" (cf. Old English hrīder "sieve")

- PIE *sth̥₂-dʰlom > *staðlom > stabulum "abode" (cf. German Stadel)

The development of *-gʰ- is twofold: *-gʰ- becomes h [ɦ] between vowels but g elsewhere:

- PIE *weǵʰ- "carry" > *weɣ-e/o > vehō (cf. Greek okhéomai "I ride", Old English wegan "to carry", Sanskrit váhati "(he) drives")

- PIE *dʰi-n-ǵʰ- "shapes, forms" > *θinɣ-e/o > fingō (cf. Old Irish -ding "erects, builds", Gothic digan "to mold, shape")

*-gʷʰ- has three outcomes, becoming gu after n, v between vowels, and g next to other consonants. All three variants are visible in the same root *snigʷʰ- "snow" (cf. Irish snigid "snows", Greek nípha):

- PIE *snigʷʰ-s > *sniɣʷs > *nigs > nom. sg. nix "snow"

- PIE *snigʷʰ-ós > *sniɣʷos > *niβis > gen. sg. nivis "of snow"

- PIE *snei-gʷʰ-e/o > *sninɣʷ-e/o (with n-infix) > ninguit "it snows"

Other examples:

- PIE *h₁le(n)gʷʰu- > *h₁legʷʰu- > *leɣʷus > *leβwi- (remade as i-stem) > levis "lightweight" (cf. Welsh llaw "small, low", Greek elakhús "small", Sanskrit laghú-, raghú- "quick, light, small")

Labiovelars[]

*gʷ has results much like non-initial *-gʷʰ, becoming v /w/ in most circumstances, but gu after a nasal and g next to other consonants:

- PIE *gʷih₃wos > *ɣʷīwos > vīvus "alive" (cf. Old Irish biu, beo, Lithuanian gývas, Sanskrit jīvá- "alive")

- PIE *gʷm̥i̯e/o- "come" > *ɣʷen-je/o > veniō (cf. English come, Greek baínō "I go", Avestan ǰamaiti "he goes", Sanskrit gam- "go")

- PIE *gʷr̥h₂us "heavy" > *ɣʷraus > grāvis (cf. Greek barús, Gothic kaúrus, Sanskrit gurú-)

- PIE *h₃engʷ- > *onɣʷ-en > unguen "salve" (cf. Old Irish imb "butter", Old High German ancho "butter", Sanskrit añjana- "anointing, ointment")

- PIE *n̥gʷén- "(swollen) gland" > *enɣʷen > inguen "bubo; groin" (cf. Greek adḗn gen. adénos "gland", Old High German ankweiz "pustules")

*kʷ remains as qu before a vowel, but reduces to c /k/ before a consonant or next to a u:

- PIE *kʷetwóres, neut. *kʷetwṓr "four" > quattuor (cf. Old Irish cethair, Lithuanian keturì, Sanskrit catvā́r-)

- PIE *sekʷ- "to follow" > sequor (cf. Old Irish sechem, Greek hépomai, Sanskrit sácate)

- PIE *leikʷ- (pres. *li-né-kʷ-) "leave behind" > *linkʷ-e/o- : *likʷ-ē- > linquō "leaves" : liceō "is allowed; is for sale" (cf. Greek leípō, limpánō, Sanskrit riṇákti, Gothic leiƕan "to lend")

- PIE *nokʷts "night" > nox, gen. sg. noctis

The sequence *p *kʷ assimilates to *kʷ *kʷ:

- PIE *pénkʷe "five" > quīnque (cf. Old Irish cóic, Greek pénte, Sanskrit páñca-)

- PIE *pérkʷus "oak" > quercus (cf. Trentino porca "fir", Punjabi pargāī "holm oak", Gothic faírƕus "world", faírgun- "mountain"[15])

- PIE *pekʷō "I cook" > *kʷekʷō > coquō (cf. coquīna, cocīnā "kitchen" vs. popīna "tavern" < Oscan, where *kʷ > p, Polish piekę "I bake", Sanskrit pacati "cooks")

The sequences *ḱw, *ǵw, *ǵʰw develop identically to *kʷ, *gʷ, *gʷʰ:

- PIE *éḱwos "horse" > *ekʷos > Old Latin equos > ecus > equus (assimilated from other forms, e.g. gen. sg. equī; cf. Sanskrit aśva-, which indicates -ḱw- not -kʷ-)

- PIE *ǵʰweh₁ro- "wild animal" > *χʷero- > ferus (cf. Greek thḗr, Lesbian phḗr, Lithuanian žvėrìs)

- PIE *mreǵʰus "short" > *mreɣu- > *mreɣwi- (remade as i-stem) > brevis (cf. Old English myrge "briefly", English merry, Greek brakhús, Avestan mǝrǝzu-, Sanskrit múhu "suddenly")

- PIE *dn̥ǵʰwéh₂[16] "tongue" > *dn̥ɣwā > *denɣʷā > Old Latin dingua > lingua

Other sequences[]

Initial *dw- (attested in Old Latin as du-) becomes b-, thus compensating for the dearth of words beginning with *b in PIE:

- PIE *dwis "twice" > duis > bis (cf. Greek dís, Sanskrit dvis)

- PIE *deu-l̥- "injure" > duellom "war" > bellum (a variant duellum survived in poetry as a trisyllabic word, whence English "duel")

S-rhotacism[]

Indo-European s between vowels was first voiced to [z] in late Proto-Italic and became r in Latin and Umbrian, a change known as rhotacism. Early Old Latin documents still have s [z], and Cicero once remarked that a certain Papirius Crassus officially changed his name from Papisius in 339 b.c.,[17] indicating the approximate time of this change. This produces many alternations in Latin declension:

- flōs "flower", gen. flōris

- mūs "mouse", pl. mūrēs

- est "he is", fut. erit "he will be"

Other examples:

- Proto-Italic *ausōs, ausōsem > *auzōs, auzōzem > aurōra "dawn" (change of suffix; cf. English east, Aeolic Greek aúōs, Sanskrit uṣā́s)

- Proto-Italic *swesōr > *swozōr > soror "sister" (cf. Old English sweostor, Sanskrit svásar)

- Proto-Italic *a(j)os, a(j)esem > *aes, aezem > aes, aerem "bronze", but PI *a(j)es-inos > *aeznos > aēnus "bronze (adj.)"

However, before another r, dissimilation occurred with sr [zr] becoming br (likely via an intermediate *ðr):

- Proto-Italic *swesr-īnos > *swezrīnos ~ *sweðrīnos > sobrīnus "maternal cousin"

- Proto-Italic *keras-rom > *kerazrom ~ *keraðrom > cerebrum "skull, brain" (cf. Greek kéras "horn")

See also[]

- De vulgari eloquentia

- Legacy of the Roman Empire

Notes[]

- ^ Leonard Robert Palmer - The Latin language - 372 pages University of Oklahoma Press, 1987 Retrieved 2012-02-01 ISBN 0-8061-2136-X

- ^ Ramat, Anna G.; Paolo Ramat (1998). The Indo-European Languages. Routledge. pp. 272–75. ISBN 0-415-06449-X.

- ^ Ramat, Anna G.; Paolo Ramat (1998). The Indo-European Languages. Routledge. p. 313. ISBN 0-415-06449-X.

- ^ Rice University .edu/~ Retrieved 2012-02-01

- ^ Allen, W. Sidney (1989). Vox Latina. Cambridge University Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 0-521-22049-1.

- ^ "What is Neo-Latin?". Archived from the original on 2016-10-09. Retrieved 2016-10-09.

- ^ Sen, Ranjan (December 2012). "Reconstructing phonological change: duration and syllable structure in Latin vowel reduction". Phonology. 29 (3): 465–504. doi:10.1017/S0952675712000231. ISSN 0952-6757.

- ^ kʷi- > ti- is normal in Attic Greek; Thessalian Greek had kís while Cypro-Arcadian had sís.

- ^ Greek is ambiguously either < *gneh₃tós or *gn̥h₃tós

- ^ Collinge, N. E. (1985). The Laws of Indo-European. John Benjamins. pp. 193–195. ISBN 90-272-3530-9.

- ^ Vine, Brent (2011). "Initial *mo- in Latin and Italic". Münchener Studien zur Sprachwissenschaft (65): 261–286.

- ^ l̥ > ol is normal in Proto-Italic.

- ^ a b Sihler, New Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin, 1995

- ^ James Clackson & Geoffrey Horrocks, The Blackwell History of the Latin Language (Oxford: Blackwell, 2007), 51-2.

- ^ Both "world" and "mountain" evolve out of the early association of oak trees with strength, cf. Latin robur = "oak" but also "strength"

- ^ PIE *dn̥ǵhwéh₂; -ǵʰw- not -gʷʰ- indicated by Old Church Slavonic języ-kŭ "tongue" < *n̥ǵhu-H-k- with loss of initial *d-; -gʷh- would yield /g/, not /z/.

- ^ Fortson, Benjamin W., Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction, p. 283

Sources[]

- Allen, J. H.; James B. Greenough (1931). New Latin Grammar. Boston: Ginn and Company. ISBN 1-58510-027-7.

- Monier-Williams, Monier (1960). A Sanskrit-English. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon.

External links[]

- Latin Etymology, An Etymological Dictionary of the Latin Language

- Latin language

- Italic language histories