Homo rhodesiensis

| Homo rhodesiensis Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

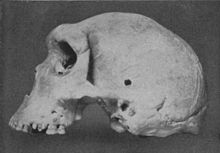

| Kabwe skull (1922 photograph) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | †H. rhodesiensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo rhodesiensis Woodward, 1921

| |

Homo rhodesiensis is the species name proposed by Arthur Smith Woodward (1921) to classify Kabwe 1 (the "Kabwe skull" or "Broken Hill skull", also "Rhodesian Man"), a Middle Stone Age fossil recovered from a cave at Broken Hill, or Kabwe, Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia).[1]. In 2020, the skull was dated to 324,000 to 274,000 years ago. Other similar older specimens also exist.[2]

Homo rhodesiensis is now mostly considered a synonym of Homo heidelbergensis, or possibly an African subspecies of Homo heidelbergensis sensu lato, understood as a polymorphic species dispersed throughout Africa and Eurasia with a range spanning the Middle Pleistocene (c. 0.8–0.12 mya).[3] Other designations such as Homo sapiens arcaicus[4] and Homo sapiens rhodesiensis[5] have also been proposed. White et al. (2003) suggested Rhodesian Man as ancestral to Homo sapiens idaltu (Herto Man).[6]

The derivation of Homo sapiens from Homo rhodesiensis has often been proposed, but is obscured by a fossil gap during 400–260 kya.[7]

Fossils[]

A number of morphologically-comparable fossil remains came to light in East Africa (Bodo, Ndutu, Eyasi, Ileret) and North Africa (Salé, Rabat, Dar-es-Soltane, Djbel Irhoud, Sidi Aberrahaman, Tighenif) during the 20th century.[8]

- Kabwe 1, also called the Broken Hill skull, or "Rhodesian Man", was assigned by Arthur Smith Woodward in 1921 as the type specimen for Homo rhodesiensis; most contemporary scientists forego the taxon "rhodesiensis" altogether and assign it to Homo heidelbergensis.[9] The cranium was discovered in Mutwe Wa Nsofu Area in a lead and zinc mine in Broken Hill, Northern Rhodesia (now Kabwe, Zambia) on June 17, 1921[10] by Tom Zwiglaar, a Swiss miner. In addition to the cranium, an upper jaw from another individual, a sacrum, a tibia, and two femur fragments were also found.

- Bodo cranium: The 600,000 year old[11] fossil was found in 1976 by members of an expedition led by Jon Kalb at Bodo D'ar in the Awash River valley of Ethiopia.[12] Although the skull is most similar to those of Kabwe, Woodward's nomenclature was discontinued and its discoverers attributed it to H. heidelbergensis.[13] It has features that represent a transition between Homo ergaster/erectus and Homo sapiens.[14]

- Ndutu cranium,[15] "the hominid from Lake Ndutu" in northern Tanzania, around 600-500,000 years old[16] or 400,000 years old. In 1976 R.J.Clarke classified it as Homo erectus and it has generally been viewed that way, although points of similarity to H. sapiens have also been recognized. After comparative studies with similar finds in Africa allocation to an African subspecies of H. sapiens was considered most appropriate by Phillip Rightmire.[17] An indirect cranial capacity estimate suggests 1100 ml. Its supratoral sulcus morphology and the presence of protuberance as suggested by Rightmire "give the Nudutu occiput an appearance which is also unlike that of Homo erectus". And in a 1989 publication Clarke concluded: "It is assigned to archaic Homo sapiens on the basis of its expanded parietal and occipital regions of the brain".[18] But Stinger (1986) pointed out that a thickened iliac pillar is typical for Homo erectus.[19] In 2016, Chris Stringer classified the cranium as belonging to Homo heidelbergensis/Homo rhodesiensis (a species considered to be intermediate between Homo erectus and Homo sapiens) rather than as early H. sapiens, but considers it to display a "more sapiens-like zygomaxillary morphology" than certain other examples of Homo rhodesiensis.[20]

- The Saldanha cranium found in 1953 in South Africa, and estimated at around 500,000 years old, was subject to at least three taxonomic revisions from 1955 to 1996.[21]

See also[]

- Homo heidelbergensis

- List of fossil sites

- List of hominina fossils

References[]

- ^ "GBIF 787018738 Fossil of Homo rhodesiensis Woodward, 1921". GBIF org. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ Grün, Rainer; Pike, Alistair; McDermott, Frank; Eggins, Stephen; Mortimer, Graham; Aubert, Maxime; Kinsley, Lesley; Joannes-Boyau, Renaud; Rumsey, Michael; Denys, Christiane; Brink, James; Clark, Tara; Stringer, Chris (2020-04-01). "Dating the skull from Broken Hill, Zambia, and its position in human evolution" (PDF). Nature. 580 (7803): 372–375. Bibcode:2020Natur.580..372G. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2165-4. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 32296179. S2CID 214736650.

- ^ Mounier, Aurélien; Condemi, Silvana; Manzi, Giorgio (April 20, 2011). "The Stem Species of Our Species: A Place for the Archaic Human Cranium from Ceprano, Italy". PLOS ONE. 6 (4): e18821. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...618821M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018821. PMC 3080388. PMID 21533096. "Ceprano clusters in our analysis with other European, African and Asian Mid-Pleistocene specimens – such as Petralona, Dali, Kabwe, Jinniu Shan, Steinheim, and SH5 – furnishing a rather plesiomorphic phenetic link among them. On the basis of this morphological affinity, it seems appropriate to group Ceprano with these fossils, and consider them as a single taxon. The available nomen for this putative species is H. heidelbergensis, whose distinctiveness stands on the retention of a number of archaic traits combined with features that are more derived and independent from any Neandertal ancestry. [...] This result would suggest that H. ergaster survived as a distinct species until 1 Ma, and would discard the validity of the species H. cepranensis [...] Thus we can include the so-called “Ante-Neandertals” from Europe in the same taxonomical unit with other Mid-Pleistocene samples from Africa and continental Asia. Combining the results of the two approaches of our phenetic analysis, Ceprano should be reasonably accommodated as part of a Mid-Pleistocene human taxon H. heidelbergensis, which would include European, African, and Asian specimens. Moreover, the combination of archaic and derived features exhibited by the Italian specimen represents a “node” connecting the different poles of such a polymorphic humanity."

- ^ H. James Birx (10 June 2010). 21st Century Anthropology: A Reference Handbook. SAGE Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-4522-6630-5.

- ^ Bernard Wood (31 March 2011). Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution, 2 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 761–762. ISBN 978-1-4443-4247-5.

- ^ White, Tim D.; Asfaw, B.; DeGusta, D.; Gilbert, H.; Richards, G. D.; Suwa, G.; Howell, F. C. (2003). "Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6491): 742–747. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..742W. doi:10.1038/nature01669. PMID 12802332. S2CID 4432091.

- ^ Hublin, J.-J. (2013), "The Middle Pleistocene Record. On the Origin of Neandertals, Modern Humans and Others" in: David R. Begun (ed.), A Companion to Paleoanthropology, John Wiley, pp. 517-537 (summary 529–531). "Most, if not all, of the African specimens assigned to H. rhodesiensis (cf heidelbergensis) seem to predate the divergence between H. neanderthalensis and H. sapiens [viz., assumed at 0.5 Mya prior to the revision by Meyer et al. 2016]. However, a gap in the fossil record, possibly between 400 and 260 ka, blurs the transition or punctuation event that separated H. rhodesiensis and H. sapiens." (p. 532).

- ^ "The evolution and development of cranial form in Homo" (PDF). Department of Anthropology, Harvard University. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ Hublin, J.-J. (2013), "The Middle Pleistocene Record. On the Origin of Neandertals, Modern Humans and Others" in: R. David Begun (ed.), A Companion to Paleoanthropology, John Wiley, pp. 517-537 (p. 523).

- ^ "Zambia resolute on recovering Broken Hill Man from Britain – Zambia Daily Mail". Daily-mail.co.zm. 2015-01-10. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- ^ "Bodo – Paleoanthropology site information". Fossilized org. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ "Bodo Skull and Jaw". Skulls Unlimited. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ "Bodo fossil". Britannica Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ "Meet Bodo and Herto There is some discussion around the species assigned to Bodo". Nutcracker Man. April 7, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ Rightmire, G. Philip (2005). "The Lake Ndutu cranium and early Homo sapiens in Africa". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 61 (2): 245–254. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330610214. PMID 6410925.

- ^ Mturi, A A (August 1976). “New hominid from Lake Ndutu, Tanzania”. Nature 262: 484-485.

- ^ Rightmire GP (June 3, 1983). "The Lake Ndutu cranium and early Homo sapiens in Africa". Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 61 (2): 245–54. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330610214. PMID 6410925.

- ^ "The Ndutu cranium and the origin of Homo sapiens – R. J. Clarke" (PDF). American Museum of Natural History. November 27, 1989. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ^ The Evolution of Homo erectus: Comparative Anatomical Studies of an Extinct Human Species By G. Philip Rightmire Published by Cambridge University Press, 1993 ISBN 0-521-44998-7, ISBN 978-0-521-44998-4 [1]

- ^ Stringer, C. (2016). "The origin and evolution of Homo sapiens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150237. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0237. PMC 4920294. PMID 27298468.

- ^ Wood, Bernard (31 March 2011). Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Human Evolution, 2 Volume Set. ISBN 9781444342475. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

Literature[]

- Woodward, Arthur Smith (1921). "A New Cave Man from Rhodesia, South Africa". Nature. 108 (2716): 371–372. Bibcode:1921Natur.108..371W. doi:10.1038/108371a0.

- Singer Robert R. and J. Wymer (1968). "Archaeological Investigation at the Saldanha Skull Site in South Africa". The South African Archaeological Bulletin. The South African Archaeological Bulletin, Vol. 23, No. 91. 23 (3): 63–73. doi:10.2307/3888485. JSTOR 3888485.

- Murrill, Rupert I. (1975). "A comparison of the Rhodesian and Petralona upper jaws in relation to other Pleistocene hominids". Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie. 66 (2): 176–187. doi:10.1127/zma/66/1975/176. PMID 806185. S2CID 3097781..

- Murrill, Rupert Ivan (1981). Ed. Charles C. Thomas (ed.). Petralona Man. A Descriptive and Comparative Study, with New Information on Rhodesian Man. Springfield, Illinois: Thomas. ISBN 0-398-04550-X.

- Rightmire, G. Philip (2005). "The Lake Ndutu cranium and early Homo sapiens in Africa". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 61 (2): 245–254. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330610214. PMID 6410925..

- Asfaw, Berhane (2005). "A new hominid parietal from Bodo, middle Awash Valley, Ethiopia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 61 (3): 367–371. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330610311. PMID 6412559..

External links[]

Media related to Homo rhodesiensis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Homo rhodesiensis at Wikimedia Commons- "Kabwe 1". The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origin Program. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

- Homo heidelbergensis

- Early species of Homo

- Fossil taxa described in 1921