Honor killing of Hatun Sürücü

Hatun "Aynur" Sürücü (also spelled Hatin Sürücü; January 17, 1982, in Berlin – February 7, 2005, in Berlin) was a Kurdish-Turkish [1] woman living in Germany[2] whose family was originally from Erzurum, Turkey. She was murdered at the age of 23 in Berlin, by her youngest brother, in an honor killing and sororicide. Sürücü had divorced the cousin she was forced to marry at the age of 16, and was reportedly dating a German man. Her murder inflamed a public debate over forced marriage in Muslim families.

Sürücü was sent to her ancestral village by her family and forced to marry a cousin there at the age of 16. She gave birth to a son, Can, in 1999. In October 1999, she fled her parents' home in Berlin, finding refuge in a home for underage mothers. She attended school, and had moved into her own apartment in the Tempelhof neighborhood of Berlin. At the time of her murder, she was at the end of her training to become an electrician.

Murder[]

On February 7, 2005, at a bus stop near her apartment, Sürücü was killed by three gunshots to the head. The police arrested three of her brothers on February 14. After several weeks of news coverage, the media began to label the murder as an honor killing, since Sürücü had received threats and reported them to police before she was killed.

Prosecution[]

In July 2005, the Berlin Public Prosecutor's office charged Sürücü's brothers with her murder. On September 14, 2005, Ayhan Sürücü, the youngest brother, confessed to murdering his sister.

In April 2006, Ayhan was sentenced to nine years and three months in prison, and his two older brothers were acquitted of charges of conspiring to murder their sister. The prosecution appealed on a point of law at the Federal Court of Justice, the Bundesgerichtshof, immediately and the 5th criminal division of the Federal Court of Justice overturned the conviction and allowed the revision. A new criminal proceeding was to take place in August 2008.[3][4]

After complete serving his sentence, Ayhan Sürücü was released from prison on July 4, 2014, deported from Germany and immediately brought to Turkey.[5]

Public outrage[]

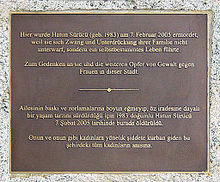

Sürücü's murder was the sixth incident of "honor" killing since October, 2004.[citation needed] On February 22, 2005, a vigil called by the Berlin Gay and Lesbian association was held at the scene of the crime, which was attended by about 100 Germans and Turks together. A second vigil, called for by German politicians and artists, was held on February 24. Sürücü's murder, and several similar cases in Germany and elsewhere in Europe have been cited by political opponents of Turkey's admission to the European Union, as an example of disregard for human rights in the Turkish culture.[citation needed] Oddly though Hatun Sürücü was of Kurdish descent.[1][2]

The Sürücü family's behaviour again sparked public outrage when Hatun's sister Arzu applied for custody of Hatun's six-year-old son Can, who has been living with a foster family in Berlin since the murder of his mother.[6] Eight months later the district court of Berlin-Tempelhof rejected the request.[7] Arzu Sürücü appealed this decision but the appeal was rejected.[8]

The public continues to demonstrate for Hatun on the anniversary of her death. Activists and citizens lay wreaths in her memory and campaign for help for girls who are faced with forced marriage and honor-related violence. Giyasettin Sayan, a Kurdish politician, complained that no Kurdish representatives were invited in demonstrations after Sürücüs murder, saying, "we are all from Turkey, but we are not all Turks."[9]

Legacy[]

A bridge in Neukölln, Berlin was named after the victim.[10]

Die Fremde (When We Leave) was the first film released in 2010 inspired by the events. [11]

A Regular Woman, a film, was made about the crime. It was released in 2019. [12]

See also[]

Honor killings in Germany:

Honor killings of people with Kurdish heritage:

- Pela Atroshi (Iraqi Kurdistan)

- Banaz Mahmod (United Kingdom)

- Fadime Şahindal (Sweden)

Honor killings of Turkish people in Turkey:

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Goll, Jo (26 July 2011). "Ehrenmord: So brachte Ayhan Sürücü seine Schwester Hatun um" – via www.welt.de.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Tatmotiv Kultur". Frankfurter Allgemeine, 02.03.2005; F.A.Z., 03.03.2005, Nr. 52 / page 37 (German).

- ^ Pressemitteilung des Bundesgerichtshofs Nr. 117/07. August 28, 2007.

- ^ "Sürücü-Mord kommt wieder vor Gericht".

- ^ Berliner Zeitung. "Verurteilt wegen "Ehrenmord": Mörder von Hatun Sürücü abgeschoben". berliner-zeitung.de.

- ^ Cleaver, Hannah (April 19, 2006). "Anger as 'honour killing' family try to adopt victim's son"[dead link]. Telegraph (UK).

- ^ "Kein Sorgerecht für Sürücüs". n-tv.de. December 20, 2006.

- ^ "Sorgerechts-Gezerre um Hatun Sürücüs Sohn". Spiegel Online. February 5, 2007.

- ^ "„Ehrenmorde": Tatmotiv Kultur". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung GmbH. 2 March 2005.

- ^ Höppner, Stephanie (2018-02-08). "'Honor killings' in Germany: When families turn executioners". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2019-12-29.

- ^ Bartlik, Silke (2010-03-11). "'Die Fremde'". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- ^ Nurtsch, Ceyda (2019-05-09). "'A Regular Woman': Remembering honor killing victim Hatun Sürücü". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2019-12-29.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hatun Sürücü. |

- 1982 births

- 2005 deaths

- German people of Kurdish descent

- Honor killing victims

- Honor killing in Europe

- German murder victims

- People murdered in Berlin

- Deaths by firearm in Germany

- 2005 crimes in Germany

- 2005 in Berlin

- Sororicides

- Turkish people murdered abroad

- Turkish murder victims

- 2000s murders in Germany

- 2005 murders in Europe