Hypersimplex

|

|

Hyperplane: |

Hyperplane: |

|---|

In polyhedral combinatorics, the hypersimplex is a convex polytope that generalizes the simplex. It is determined by two integers and , and is defined as the convex hull of the -dimensional vectors whose coefficients consist of ones and zeros. Equivalently, can be obtained by slicing the -dimensional unit hypercube with the hyperplane of equation and, for this reason, it is a -dimensional polytope when .[1]

Properties[]

The number of vertices of is .[1] The graph formed by the vertices and edges of the hypersimplex is the Johnson graph .[2]

Alternative constructions[]

An alternative construction (for ) is to take the convex hull of all -dimensional -vectors that have either or nonzero coordinates. This has the advantage of operating in a space that is the same dimension as the resulting polytope, but the disadvantage that the polytope it produces is less symmetric (although combinatorially equivalent to the result of the other construction).

The hypersimplex is also the matroid polytope for a uniform matroid with elements and rank .[3]

Examples[]

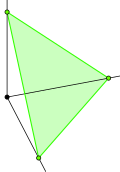

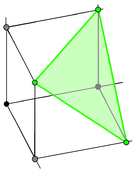

The hypersimplex is a -simplex (and therefore, it has vertices). The hypersimplex is an octahedron, and the hypersimplex is a rectified 5-cell.

Generally, the hypersimplex, , corresponds to a uniform polytope, being the -rectified -dimensional simplex, with vertices positioned at the center of all the -dimensional faces of a -dimensional simplex.

| Name | Equilateral triangle |

Tetrahedron (3-simplex) |

Octahedron | 5-cell (4-simplex) |

Rectified 5-cell |

5-simplex | Rectified 5-simplex |

Birectified 5-simplex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δd,k = (d,k) = (d,d − k) |

(3,1) (3,2) |

(4,1) (4,3) |

(4,2) | (5,1) (5,4) |

(5,2) (5,3) |

(6,1) (6,5) |

(6,2) (6,4) |

(6,3) |

| Vertices |

3 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 6 | 15 | 20 |

| d-coordinates | (0,0,1) (0,1,1) |

(0,0,0,1) (0,1,1,1) |

(0,0,1,1) | (0,0,0,0,1) (0,1,1,1,1) |

(0,0,0,1,1) (0,0,1,1,1) |

(0,0,0,0,0,1) (0,1,1,1,1,1) |

(0,0,0,0,1,1) (0,0,1,1,1,1) |

(0,0,0,1,1,1) |

| Image |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Graphs |  J(3,1) = K2 |

J(4,1) = K3 |

J(4,2) = T(6,3) |

J(5,1) = K4 |

J(5,2) |

J(6,1) = K5 |

J(6,2) |

J(6,3) |

| Coxeter diagrams |

||||||||

| Schläfli symbols |

{3} = r{3} |

{3,3} = 2r{3,3} |

r{3,3} = {3,4} | {3,3,3} = 3r{3,3,3} |

r{3,3,3} = 2r{3,3,3} |

{3,3,3,3} = 4r{3,3,3,3} |

r{3,3,3,3} = 3r{3,3,3,3} |

2r{3,3,3,3} |

| Facets | { } | {3} | {3,3} | {3,3}, {3,4} | {3,3,3} | {3,3,3}, r{3,3,3} | r{3,3,3} | |

History[]

The hypersimplices were first studied and named in the computation of characteristic classes (an important topic in algebraic topology), by Gabrièlov, Gelʹfand & Losik (1975).[4][5]

References[]

- ^ a b Miller, Ezra; Reiner, Victor; Sturmfels, Bernd, Geometric Combinatorics, IAS/Park City mathematics series, vol. 13, American Mathematical Society, p. 655, ISBN 9780821886953.

- ^ Rispoli, Fred J. (2008), The graph of the hypersimplex, arXiv:0811.2981, Bibcode:2008arXiv0811.2981R.

- ^ Grötschel, Martin (2004), "Cardinality homogeneous set systems, cycles in matroids, and associated polytopes", The Sharpest Cut: The Impact of Manfred Padberg and His Work, MPS/SIAM Ser. Optim., SIAM, Philadelphia, PA, pp. 99–120, MR 2077557. See in particular the remarks following Prop. 8.20 on p. 114.

- ^ Gabrièlov, A. M.; Gelʹfand, I. M.; Losik, M. V. (1975), "Combinatorial computation of characteristic classes. I, II", Akademija Nauk SSSR, 9 (2): 12–28, ibid. 9 (1975), no. 3, 5–26, MR 0410758.

- ^ Ziegler, Günter M. (1995), Lectures on Polytopes, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 152, Springer-Verlag, New York, p. 20, doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-8431-1, ISBN 0-387-94365-X, MR 1311028.

Further reading[]

- Hibi, Takayuki; Solus, Liam (2016), "Facets of the r-stable (n,k)-hypersimplex", Annals of Combinatorics, 20: 815–829, arXiv:1408.5932, Bibcode:2014arXiv1408.5932H, doi:10.1007/s00026-016-0325-x.

- Polytopes

![[0,1]^{d}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e13ae4917276744b214714a20b3cb8ee305e309d)