Information technology

| Information science |

|---|

| General aspects |

| Related fields and sub-fields |

Information technology (IT) is the use of computers to create, process, store, and exchange all kinds of electronic data[1] and information. IT is typically used within the context of business operations as opposed to personal or entertainment technologies.[2] IT is considered to be a subset of information and communications technology (ICT). An information technology system (IT system) is generally an information system, a communications system, or, more specifically speaking, a computer system – including all hardware, software, and peripheral equipment – operated by a limited group of IT users.

Humans have been storing, retrieving, manipulating, and communicating information since the Sumerians in Mesopotamia developed writing in about 3000 BC.[3] However, the term information technology in its modern sense first appeared in a 1958 article published in the Harvard Business Review; authors Harold J. Leavitt and Thomas L. Whisler commented that "the new technology does not yet have a single established name. We shall call it information technology (IT)." Their definition consists of three categories: techniques for processing, the application of statistical and mathematical methods to decision-making, and the simulation of higher-order thinking through computer programs.[4]

The term is commonly used as a synonym for computers and computer networks, but it also encompasses other information distribution technologies such as television and telephones. Several products or services within an economy are associated with information technology, including computer hardware, software, electronics, semiconductors, internet, telecom equipment, and e-commerce.[5][a]

Based on the storage and processing technologies employed, it is possible to distinguish four distinct phases of IT development: pre-mechanical (3000 BC – 1450 AD), mechanical (1450–1840), electromechanical (1840–1940), and electronic (1940–present).[3] This article focuses on the most recent period (electronic).

History of computer technology[]

Devices have been used to aid computation for thousands of years, probably initially in the form of a tally stick.[7] The Antikythera mechanism, dating from about the beginning of the first century BC, is generally considered to be the earliest known mechanical analog computer, and the earliest known geared mechanism.[8] Comparable geared devices did not emerge in Europe until the 16th century, and it was not until 1645 that the first mechanical calculator capable of performing the four basic arithmetical operations was developed.[9]

Electronic computers, using either relays or valves, began to appear in the early 1940s. The electromechanical Zuse Z3, completed in 1941, was the world's first programmable computer, and by modern standards one of the first machines that could be considered a complete computing machine. During the Second World War, Colossus developed the first electronic digital computer to decrypt German messages. Although it was programmable, it was not general-purpose, being designed to perform only a single task. It also lacked the ability to store its program in memory; programming was carried out using plugs and switches to alter the internal wiring.[10] The first recognizably modern electronic digital stored-program computer was the Manchester Baby, which ran its first program on 21 June 1948.[11]

The development of transistors in the late 1940s at Bell Laboratories allowed a new generation of computers to be designed with greatly reduced power consumption. The first commercially available stored-program computer, the Ferranti Mark I, contained 4050 valves and had a power consumption of 25 kilowatts. By comparison, the first transistorized computer developed at the University of Manchester and operational by November 1953, consumed only 150 watts in its final version.[12]

Several other breakthroughs in semiconductor technology include the integrated circuit (IC) invented by Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments and Robert Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1959, the metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor (MOSFET) invented by Mohamed Atalla and Dawon Kahng at Bell Laboratories in 1959, and the microprocessor invented by Ted Hoff, Federico Faggin, Masatoshi Shima and Stanley Mazor at Intel in 1971. These important inventions led to the development of the personal computer (PC) in the 1970s, and the emergence of information and communications technology (ICT).[13]

Electronic data processing[]

Data storage[]

Early electronic computers such as Colossus made use of punched tape, a long strip of paper on which data was represented by a series of holes, a technology now obsolete.[14] Electronic data storage, which is used in modern computers, dates from World War II, when a form of delay line memory was developed to remove the clutter from radar signals, the first practical application of which was the mercury delay line.[15] The first random-access digital storage device was the Williams tube, based on a standard cathode ray tube,[16] but the information stored in it and delay line memory was volatile in that it had to be continuously refreshed, and thus was lost once power was removed. The earliest form of non-volatile computer storage was the magnetic drum, invented in 1932[17] and used in the Ferranti Mark 1, the world's first commercially available general-purpose electronic computer.[18]

IBM introduced the first hard disk drive in 1956, as a component of their 305 RAMAC computer system.[19]:6 Most digital data today is still stored magnetically on hard disks, or optically on media such as CD-ROMs.[20]:4–5 Until 2002 most information was stored on analog devices, but that year digital storage capacity exceeded analog for the first time. As of 2007, almost 94% of the data stored worldwide was held digitally:[21] 52% on hard disks, 28% on optical devices ,and 11% on digital magnetic tape. It has been estimated that the worldwide capacity to store information on electronic devices grew from less than 3 exabytes in 1986 to 295 exabytes in 2007,[22] doubling roughly every 3 years.[23]

Databases[]

Database Management Systems (DMS) emerged in the 1960s to address the problem of storing and retrieving large amounts of data accurately and quickly. An early such system was IBM's Information Management System (IMS),[24] which is still widely deployed more than 50 years later.[25] IMS stores data hierarchically,[24] but in the 1970s Ted Codd proposed an alternative relational storage model based on set theory and predicate logic and the familiar concepts of tables, rows ,and columns. In 1981, the first commercially available relational database management system (RDBMS) was released by Oracle.[26]

All DMS consist of components, they allow the data they store to be accessed simultaneously by many users while maintaining its integrity.[27] All databases are common in one point that the structure of the data they contain is defined and stored separately from the data itself, in a database schema.[24]

In recent years, the extensible markup language (XML) has become a popular format for data representation. Although XML data can be stored in normal file systems, it is commonly held in relational databases to take advantage of their "robust implementation verified by years of both theoretical and practical effort".[28] As an evolution of the Standard Generalized Markup Language (SGML), XML's text-based structure offers the advantage of being both machine and human-readable.[29]

Data retrieval[]

The relational database model introduced a programming-language independent Structured Query Language (SQL), based on relational algebra.

The terms "data" and "information" are not synonymous. Anything stored is data, but it only becomes information when it is organized and presented meaningfully.[30]:1–9 Most of the world's digital data is unstructured, and stored in a variety of different physical formats[31][b] even within a single organization. Data warehouses began to be developed in the 1980s to integrate these disparate stores. They typically contain data extracted from various sources, including external sources such as the Internet, organized in such a way as to facilitate decision support systems (DSS).[32]:4–6

Data transmission[]

Data transmission has three aspects: transmission, propagation, and reception.[33] It can be broadly categorized as broadcasting, in which information is transmitted unidirectionally downstream, or telecommunications, with bidirectional upstream and downstream channels.[22]

XML has been increasingly employed as a means of data interchange since the early 2000s,[34] particularly for machine-oriented interactions such as those involved in web-oriented protocols such as SOAP,[29] describing "data-in-transit rather than... data-at-rest".[34]

Data manipulation[]

Hilbert and Lopez identify the exponential pace of technological change (a kind of Moore's law): machines' application-specific capacity to compute information per capita roughly doubled every 14 months between 1986 and 2007; the per capita capacity of the world's general-purpose computers doubled every 18 months during the same two decades; the global telecommunication capacity per capita doubled every 34 months; the world's storage capacity per capita required roughly 40 months to double (every 3 years); and per capita broadcast information has doubled every 12.3 years.[22]

Massive amounts of data are stored worldwide every day, but unless it can be analyzed and presented effectively it essentially resides in what have been called data tombs: "data archives that are seldom visited".[35] To address that issue, the field of data mining – "the process of discovering interesting patterns and knowledge from large amounts of data"[36] – emerged in the late 1980s.[37]

Perspectives[]

Academic perspective[]

In an academic context, the Association for Computing Machinery defines IT as "undergraduate degree programs that prepare students to meet the computer technology needs of business, government, healthcare, schools, and other kinds of organizations .... IT specialists assume responsibility for selecting hardware and software products appropriate for an organization, integrating those products with organizational needs and infrastructure, and installing, customizing, and maintaining those applications for the organization’s computer users."[38]

Undergraduate degrees in IT (B.S., A.S.) are similar to other computer science degrees. In fact, they often times have the same foundational level courses. Computer science (CS) programs tend to focus more on theory and design, whereas Information Technology programs are structured to equip the graduate with expertise in the practical application of technology solutions to support modern business and user needs.

Commercial and employment perspective[]

Companies in the information technology field are often discussed as a group as the "tech sector" or the "tech industry".[39][40][41] These titles can be misleading at times and should not be mistaken for “tech companies”; which are generally large scale, for-profit corporations that sell consumer technology and software. It is also worth noting that from a business perspective, Information Technology departments are a “cost center” the majority of the time. A cost center is a department or staff which incurs expenses, or “costs”, within a company rather than generating profits or revenue streams. Modern businesses rely heavily on technology for their day-to-day operations, so the expenses delegated to cover technology that facilitates business in a more efficient manner is usually seen as “just the cost of doing business”. IT departments are allocated funds by senior leadership and must attempt to achieve the desired deliverables while staying within that budget. Government and the private sector might have different funding mechanisms, but the principles are more-or-less the same. This is an often overlooked reason for the rapid interest in automation and Artificial Intelligence, but the constant pressure to do more with less is opening the door for automation to take control of at least some minor operations in large companies.

Many companies now have IT departments for managing the computers, networks, and other technical areas of their businesses. Companies have also sought to integrate IT with business outcomes and decision-making through a BizOps or business operations department.[42]

In a business context, the Information Technology Association of America has defined information technology as "the study, design, development, application, implementation, support or management of computer-based information systems".[43][page needed] The responsibilities of those working in the field include network administration, software development and installation, and the planning and management of an organization's technology life cycle, by which hardware and software are maintained, upgraded, and replaced.

Information services[]

Information services is a term somewhat loosely applied to a variety of IT-related services offered by commercial companies,[44][45][46] as well as data brokers.

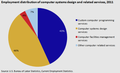

U.S. Employment distribution of computer systems design and related services, 2011[47]

U.S. Employment in the computer systems and design related services industry, in thousands, 1990-2011[47]

U.S. Occupational growth and wages in computer systems design and related services, 2010-2020[47]

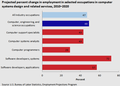

U.S. projected percent change in employment in selected occupations in computer systems design and related services, 2010-2020[47]

U.S. projected average annual percent change in output and employment in selected industries, 2010-2020[47]

Ethical perspectives[]

The field of information ethics was established by mathematician Norbert Wiener in the 1940s.[48]:9 Some of the ethical issues associated with the use of information technology include:[49]:20–21

- Breaches of copyright by those downloading files stored without the permission of the copyright holders

- Employers monitoring their employees' emails and other Internet usage

- Unsolicited emails

- Hackers accessing online databases

- Web sites installing cookies or spyware to monitor a user's online activities, which may be used by data brokers

See also[]

- Center for Minorities and People with Disabilities in Information Technology

- Computing

- Computer science

- Data processing

- Health information technology

- Information and communications technology (ICT)

- Information management

- Journal of Cases on Information Technology

- Knowledge society

- List of largest technology companies by revenue

- Operational technology

- Outline of information technology

- World Information Technology and Services Alliance

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ On the later more broad application of the term IT, Keary comments: "In its original application 'information technology' was appropriate to describe the convergence of technologies with application in the vast field of data storage, retrieval, processing, and dissemination. This useful conceptual term has since been converted to what purports to be of great use, but without the reinforcement of definition ... the term IT lacks substance when applied to the name of any function, discipline, or position."[6]

- ^ "Format" refers to the physical characteristics of the stored data such as its encoding scheme; "structure" describes the organisation of that data.

Citations[]

- ^ Daintith, John, ed. (2009), "IT", A Dictionary of Physics, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199233991, retrieved 1 August 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ "Free on-line dictionary of computing (FOLDOC)". Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Butler, Jeremy G., A History of Information Technology and Systems, University of Arizona, retrieved 2 August 2012

- ^ Leavitt, Harold J.; Whisler, Thomas L. (1958), "Management in the 1980s", Harvard Business Review, 11

- ^ Chandler, Daniel; Munday, Rod (10 February 2011), "Information technology", A Dictionary of Media and Communication (first ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199568758, retrieved 1 August 2012,

Commonly a synonym for computers and computer networks but more broadly designating any technology that is used to generate, store, process, and/or distribute information electronically, including television and telephone.

- ^ Ralston, Hemmendinger & Reilly (2000), p. 869

- ^ Schmandt-Besserat, Denise (1981), "Decipherment of the earliest tablets", Science, 211 (4479): 283–85, Bibcode:1981Sci...211..283S, doi:10.1126/science.211.4479.283, PMID 17748027

- ^ Wright (2012), p. 279

- ^ Chaudhuri (2004), p. 3

- ^ Lavington (1980), p. 11

- ^ Enticknap, Nicholas (Summer 1998), "Computing's Golden Jubilee", Resurrection (20), ISSN 0958-7403, archived from the original on 9 January 2012, retrieved 19 April 2008

- ^ Cooke-Yarborough, E. H. (June 1998), "Some early transistor applications in the UK", Engineering Science & Education Journal, 7 (3): 100–106, doi:10.1049/esej:19980301, ISSN 0963-7346

- ^ "Advanced information on the Nobel Prize in Physics 2000" (PDF). Nobel Prize. June 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ Alavudeen & Venkateshwaran (2010), p. 178

- ^ Lavington (1998), p. 1

- ^ "Early computers at Manchester University", Resurrection, 1 (4), Summer 1992, ISSN 0958-7403, archived from the original on 28 August 2017, retrieved 19 April 2008

- ^ Universität Klagenfurt (ed.), "Magnetic drum", Virtual Exhibitions in Informatics, retrieved 21 August 2011

- ^ The Manchester Mark 1, University of Manchester, archived from the original on 21 November 2008, retrieved 24 January 2009

- ^ Khurshudov, Andrei (2001), The Essential Guide to Computer Data Storage: From Floppy to DVD, Prentice Hall, ISBN 978-0-130-92739-2

- ^ Wang, Shan X.; Taratorin, Aleksandr Markovich (1999), Magnetic Information Storage Technology, Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12-734570-3

- ^ Wu, Suzanne, "How Much Information Is There in the World?", USC News, University of Southern California, retrieved 10 September 2013

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hilbert, Martin; López, Priscila (1 April 2011), "The World's Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information", Science, 332 (6025): 60–65, Bibcode:2011Sci...332...60H, doi:10.1126/science.1200970, PMID 21310967, S2CID 206531385, retrieved 10 September 2013

- ^ "Americas events- Video animation on The World's Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information from 1986 to 2010". The Economist. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ward & Dafoulas (2006), p. 2

- ^ Olofson, Carl W. (October 2009), A Platform for Enterprise Data Services (PDF), IDC, retrieved 7 August 2012

- ^ Ward & Dafoulas (2006), p. 3

- ^ Silberschatz, Abraham (2010). Database System Concepts. McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 978-0-07-741800-7.

- ^ Pardede (2009), p. 2

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pardede (2009), p. 4

- ^ Kedar, Seema (2009). Database Management System. Technical Publications. ISBN 9788184316049.

- ^ van der Aalst (2011), p. 2

- ^ Dyché, Jill (2000), Turning Data Into Information With Data Warehousing, Addison Wesley, ISBN 978-0-201-65780-7

- ^ Weik (2000), p. 361

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pardede (2009), p. xiii

- ^ Han, Kamber & Pei (2011), p. 5

- ^ Han, Kamber & Pei (2011), p. 8

- ^ Han, Kamber & Pei (2011), p. xxiii

- ^ The Joint Task Force for Computing Curricula 2005.Computing Curricula 2005: The Overview Report (pdf) Archived 21 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Technology Sector Snapshot". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Our programmes, campaigns and partnerships". TechUK. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Cyberstates 2016". CompTIA. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Manifesto Hatched to Close Gap Between Business and IT | IT Leadership | TechNewsWorld". www.technewsworld.com. 22 October 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Proctor, K. Scott (2011), Optimizing and Assessing Information Technology: Improving Business Project Execution, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-118-10263-3

- ^ "Top Information Services companies". VentureRadar. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Follow Information Services on Index.co". Index.co. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ Publishing, Value Line. "Industry Overview: Information Services". Value Line. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Lauren Csorny (9 April 2013). "U.S. Careers in the growing field of information technology services : Beyond the Numbers: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics". bls.gov.

- ^ Bynum, Terrell Ward (2008), "Norbert Wiener and the Rise of Information Ethics", in van den Hoven, Jeroen; Weckert, John (eds.), Information Technology and Moral Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-85549-5

- ^ Reynolds, George (2009), Ethics in Information Technology, Cengage Learning, ISBN 978-0-538-74622-9

Bibliography[]

- Alavudeen, A.; Venkateshwaran, N. (2010), Computer Integrated Manufacturing, PHI Learning, ISBN 978-81-203-3345-1

- Chaudhuri, P. Pal (2004), Computer Organization and Design, PHI Learning, ISBN 978-81-203-1254-8

- Han, Jiawei; Kamber, Micheline; Pei, Jian (2011), Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques (3rd ed.), Morgan Kaufmann, ISBN 978-0-12-381479-1

- Lavington, Simon (1980), Early British Computers, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-0810-8

- Lavington, Simon (1998), A History of Manchester Computers (2nd ed.), The British Computer Society, ISBN 978-1-902505-01-5

- Pardede, Eric (2009), Open and Novel Issues in XML Database Applications, Information Science Reference, ISBN 978-1-60566-308-1

- Ralston, Anthony; Hemmendinger, David; Reilly, Edwin D., eds. (2000), Encyclopedia of Computer Science (4th ed.), Nature Publishing Group, ISBN 978-1-56159-248-7

- van der Aalst, Wil M. P. (2011), Process Mining: Discovery, Conformance and Enhancement of Business Processes, Springer, ISBN 978-3-642-19344-6

- Ward, Patricia; Dafoulas, George S. (2006), Database Management Systems, Cengage Learning EMEA, ISBN 978-1-84480-452-8

- Weik, Martin (2000), Computer Science and Communications Dictionary, 2, Springer, ISBN 978-0-7923-8425-0

- Wright, Michael T. (2012), "The Front Dial of the Antikythera Mechanism", in Koetsier, Teun; Ceccarelli, Marco (eds.), Explorations in the History of Machines and Mechanisms: Proceedings of HMM2012, Springer, pp. 279–292, ISBN 978-94-007-4131-7

Further reading[]

- Allen, T.; Morton, M. S. Morton, eds. (1994), Information Technology and the Corporation of the 1990s, Oxford University Press

- Gitta, Cosmas and South, David (2011). Southern Innovator Magazine Issue 1: Mobile Phones and Information Technology: United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation. ISSN 2222-9280

- Gleick, James (2011).The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Price, Wilson T. (1981), Introduction to Computer Data Processing, Holt-Saunders International Editions, ISBN 978-4-8337-0012-2

- Shelly, Gary, Cashman, Thomas, Vermaat, Misty, and Walker, Tim. (1999). Discovering Computers 2000: Concepts for a Connected World. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Course Technology.

- Webster, Frank, and Robins, Kevin. (1986). Information Technology – A Luddite Analysis. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

External links[]

Learning materials related to Information technology at Wikiversity

Learning materials related to Information technology at Wikiversity Media related to Information technology at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Information technology at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Information technology at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Information technology at Wikiquote

- Information technology

- Mass media technology

- Computers