Inside Job (2010 film)

| Inside Job | |

|---|---|

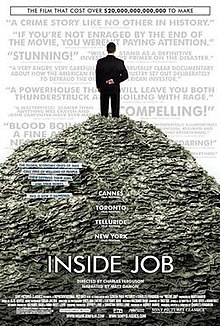

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Charles Ferguson |

| Produced by | Audrey Marrs Charles Ferguson |

| Narrated by | Matt Damon |

| Cinematography | Svetlana Cvetko Kalyanee Mam |

| Edited by | Chad Beck Adam Bolt |

| Music by | Alex Heffes |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Classics |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 108 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million[1] |

| Box office | $7.9 million[2] |

Inside Job is a 2010 American documentary film, directed by Charles Ferguson, about the late-2000s financial crisis. Ferguson, who began researching in 2008,[3] says the film is about "the systemic corruption of the United States by the financial services industry and the consequences of that systemic corruption",[4] amongst them conflicts of interest of academic research which led to improved disclosure standards by the American Economic Association.[5] In five parts, the film explores how changes in the policy environment and banking practices helped create the financial crisis.

Inside Job was acclaimed by film critics, who praised its pacing, research and exposition of complex material. It screened at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival in May and won the 2010 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

Synopsis[]

This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (November 2021) |

The documentary is split into five parts. It begins by examining how Iceland was highly deregulated in 2000 and the privatization of its banks. When Lehman Brothers went bankrupt and AIG collapsed, Iceland and the rest of the world went into a global recession. At the Federal Reserve annual Jackson Hole conference in 2005, Raghuram Rajan, then the chief economist of IMF, warned about the growing risks in the financial system and proposed policies that would reduce such risks. Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers called the warnings "misguided" and Rajan himself a "luddite". However, following the financial crisis of 2007–2008, Rajan's views were seen as prescient and he was extensively interviewed for this movie.

Part I: How We Got Here[]

The American financial industry was regulated from 1941 to 1981, followed by a long period of deregulation. At the end of the 1980s, a savings and loan crisis cost taxpayers about $124 billion. In the late 1990s, the financial sector had consolidated into a few giant firms. In March 2000, the Internet Stock Bubble burst because investment banks promoted Internet companies that they knew would fail, resulting in $5 trillion in investor losses. In the 1990s, derivatives became popular in the industry and added instability. Efforts to regulate derivatives were thwarted by the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, backed by several key officials. In the 2000s, the industry was dominated by five investment banks (Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, and Bear Stearns), two financial conglomerates (Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase), three securitized insurance companies (AIG, MBIA, AMBAC) and the three rating agencies (Moody’s, Standard & Poor's, Fitch). Investment banks bundled mortgages with other loans and debts into collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), which they sold to investors. Rating agencies gave many CDOs AAA ratings. Subprime loans led to predatory lending. Many home owners were given loans they could never repay.

Part II: The Bubble (2001–2007)[]

During the housing boom, the ratio of money borrowed by an investment bank versus the bank's own assets reached unprecedented levels. The credit default swap (CDS), was akin to an insurance policy. Speculators could buy CDSs to bet against CDOs they did not own. Numerous CDOs were backed by subprime mortgages. Goldman-Sachs sold more than $3 billion worth of CDOs in the first half of 2006. Goldman also bet against the low-value CDOs, telling investors they were high-quality. The three biggest ratings agencies contributed to the problem. AAA-rated instruments rocketed from a mere handful in 2000 to over 4,000 in 2006.

Part III: The Crisis[]

The market for CDOs collapsed and investment banks were left with hundreds of billions of dollars in loans, CDOs, and real estate they could not unload. The Great Recession began in November 2007, and in March 2008, Bear Stearns ran out of cash. In September, the federal government took over Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which had been on the brink of collapse. Two days later, Lehman Brothers collapsed. These entities all had AA or AAA ratings within days of being bailed out. Merrill Lynch, on the edge of collapse, was acquired by Bank of America. Henry Paulson and Timothy Geithner decided that Lehman must go into bankruptcy, which resulted in a collapse of the commercial paper market. On September 17, the insolvent AIG was taken over by the government. The next day, Paulson and Fed chairman Ben Bernanke asked Congress for $700 billion to bail out the banks. The global financial system became paralyzed. On October 3, 2008, President George W. Bush signed the Troubled Asset Relief Program, but global stock markets continued to fall. Layoffs and foreclosures continued with unemployment rising to 10% in the U.S.A. and the European Union. By December 2008, GM and Chrysler also faced bankruptcy. Foreclosures in the U.S. reached unprecedented levels.

Part IV: Accountability[]

Top executives of the insolvent companies walked away with their personal fortunes intact. The executives had hand-picked their boards of directors, which handed out billions in bonuses after the government bailout. The major banks grew in power and doubled anti-reform efforts. Academic economists had for decades advocated for deregulation and helped shape U.S. policy. They still opposed reform after the 2008 crisis. Some of the consulting firms involved were the Analysis Group, Charles River Associates, Compass Lexecon, and the Law and Economics Consulting Group (LECG). Many of these economists had conflicts of interest, collecting sums as consultants to companies and other groups involved in the financial crisis.[6]

Part V: Where We Are Now[]

Tens of thousands of U.S. factory workers were laid off. The incoming Obama administration’s financial reforms were weak, and there was no significant proposed regulation of the practices of ratings agencies, lobbyists, and executive compensation. Geithner became Treasury Secretary. Martin Feldstein, Laura Tyson and Lawrence Summers were all top economic advisers to Obama. Bernanke was reappointed Fed Chair. European nations imposed strict regulations on bank compensation, but the U.S. resisted them.

Reception[]

The film was met with critical acclaim. On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 98% based on 147 reviews, with an average rating of 8.21/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Disheartening but essential viewing, Charles Ferguson's documentary explores the 2008 Global Financial Crisis with exemplary rigor."[7] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 88 out of 100, based on 27 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[8]

Roger Ebert described the film as "an angry, well-argued documentary about how the American housing industry set out deliberately to defraud the ordinary American investor".[9] A. O. Scott of The New York Times wrote that "Mr. Ferguson has summoned the scourging moral force of a pulpit-shaking sermon. That he delivers it with rigor, restraint and good humor makes his case all the more devastating".[10] Logan Hill of New York magazine characterized the film as a "rip-snorting, indignant documentary", noting the "effective presence" of narrator Matt Damon.[11] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian said the film was "as gripping as any thriller". He went on to say that it was obviously influenced by Michael Moore, describing it as "a Moore film with the gags and stunts removed".[12] In 2011, a Metacritic editor ranked the film first on the subject of the 2008 financial crisis.[13]

The film was selected for a special screening at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival. A reviewer writing from Cannes characterized the film as "a complex story told exceedingly well and with a great deal of unalloyed anger".[14]

Accolades[]

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[15] | February 27, 2011 | Best Documentary Feature | Charles H. Ferguson and Audrey Marrs | Won |

| Chicago Film Critics Association Awards[16] | December 20, 2010 | Best Documentary Feature | Nominated | |

| Directors Guild of America Awards[17] | December 29, 2010 | Best Documentary | Won | |

| Gotham Independent Film Awards[18] | November 29, 2010 | Best Documentary | Nominated | |

| Online Film Critics Society Awards[19] | January 3, 2011 | Best Documentary | Nominated | |

| Writers Guild of America Awards[20] | February 5, 2011 | Best Documentary Screenplay | Won |

See also[]

- Financial crisis of 2007–08

- Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008

- Troubled Asset Relief Program

- DISCLOSE Act

- Wall Street reform

- Systemic corruption

Films and series[]

- The Mayfair Set (1999)

- I.O.U.S.A. (2008)

- Let's Make Money (2008)

- Capitalism: A Love Story (2009)

- Generation Zero (2010)

- Debtocracy (2011)

- Too Big to Fail (2011)

- Heist: Who Stole the American Dream? (2011)

- The Big Short (2015)

- Margin Call (2011)

- The Last Days of Lehman Brothers (2009)

References[]

- ^ (March 2, 2011). "Adam Lashinsky interviews Charles Ferguson regarding 'Inside Job' at the Commonwealth Club" on YouTube. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ "Inside Job (2010)". boxofficemojo.com. IMDb. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ www

.npr .org /templates /story /story .php?storyId=130272396 - ^ (February 25, 2011), "Charlie Rose Interviews Charles Ferguson on his documentary 'Inside Job'" on YouTube. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ www

.wsj .com /articles /SB10001424052970204294504576613032849864232 - ^ Casselman, Ben (January 9, 2012). "Economists Set Rules on Ethics". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ^ "Inside Job". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ "Inside Job Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 13, 2010). "Inside Job". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ Scott, A.O. (October 7, 2010). "Who Maimed the Economy, and How". The New York Times. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ Hill, Logan (May 16, 2010). "Is Matt Damon's Narration of a Cannes Doc a Sign that Hollywood is Abandoning Obama?". New York Magazine. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (February 17, 2011). "Inside Job Review". The Guardian.

- ^ "Ranked: Films about the Ongoing Financial Crisis".

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (May 16, 2010). "At Cannes, the Economy Is On-Screen". The New York Times. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- ^ "Nominees for the 83rd Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ^ "Chicago Film Critics Awards — 2008–2010". Chicago Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on February 24, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg. "DGA 2011 Award Winners Announced". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ Adams, Ryan (October 18, 2010). "2010 Gotham Independent Film Award Nominations". AwardsDaily. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

Adams, Ryan (November 29, 2010). "20th Anniversary Gotham Independent Award winners". Awards Daily. Retrieved January 26, 2011. - ^ Stone, Sarah (December 27, 2010). "Online Film Critics Society Nominations". Awards Daily. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

Stone, Sarah (January 3, 2011). "The Social Network Named Best Film by the Online Film Critics". Awards Daily. Retrieved January 26, 2011. - ^ "Writer's Guild of America 2011 Awards Winners". Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on 2012-01-02. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

External links[]

- 2010 films

- English-language films

- 2010 documentary films

- American documentary films

- American films

- Best Documentary Feature Academy Award winners

- Documentary films about American politics

- Documentary films about business

- Documentary films about the Great Recession

- Wall Street films

- Films about financial crises

- Films scored by Alex Heffes

- Sony Pictures Classics films