Islamic State – West Africa Province

| Islamic State's West Africa Province | |

|---|---|

| ولاية غرب أفريقيا West African Province | |

Flag of the Islamic State | |

| Dates of operation | 2015 – 2016 (as unified group) 2016 – present (after split) |

| Split from | Boko Haram |

| Group(s) | Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (formally) |

| Active regions | Chad Basin |

| Ideology | Salafi jihadist Islamism |

| Size | c. 5,000 (2019) |

| Part of | |

| Opponents | Boko Haram |

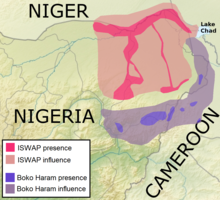

The Islamic State's West Africa Province (ISWAP)[a] is a militant group and administrative division of the Islamic State (IS), a Salafi jihadist militant group and unrecognised proto-state. ISWAP is primarily active in the Chad Basin, and fights an extensive insurgency against the states of Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, and Niger. It is an offshoot of Boko Haram with which it has a violent rivalry; Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau killed himself in battle with ISWAP in 2021. ISWAP is the umbrella organization for all IS factions in West Africa including the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (IS-GS), although the actual ties between ISWAP and IS-GS are limited.

Name[]

The Islamic State's West Africa Province is officially termed "Wilāyat Garb Ifrīqīyā" (Arabic: ولاية غرب أفريقيا), meaning "West African Province".[1] It is known by a variety of óther names and abbreviations such as "ISWAP", "IS-WA", and "ISIS-WA".[2] Since ISWAP has formally absorbed IS-GS, it has also been differentiated by experts into two branches, namely "ISWAP-Lake Chad" and "ISWAP-Greater Sahara".[3]

History[]

ISWAP's origins date back to the emergence of Boko Haram, a Salafi jihadist movement centred in Borno State in northeastern Nigeria. The movement launched an insurgency against the Nigerian government following an unsuccessful uprising in 2009, aiming at establishing an Islamic state in northern Nigeria,[4] and neighbouring regions of Cameroon, Chad and Niger. Its de facto leader Abubakar Shekau attempted to increase his international standing among Islamists by allying with the prominent Islamic State (IS) in March 2015. Boko Haram thus became the "Islamic State's West Africa Province" (ISWAP).[5][6][2]

When the insurgents were subsequently defeated and lost almost all of their lands during the 2015 West African offensive by the Multinational Joint Task Force (MJTF), discontent grew among the rebels.[5][6][7] Despite orders by the ISIL's central command to stop using women and children suicide bombers as well as refrain from mass killings of civilians, Shekau refused to change his tactics.[8] Researcher Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi summarized that the Boko Haram leader proved to be "too extreme even by the Islamic State's standards".[9] Shekau had always refused to fully submit to ISIL's central command, and the latter consequently removed him as leader of ISWAP in August 2016. Shekau responded by breaking with ISIL's central command, but many of the rebels stayed loyal to IS. As a result, the rebel movement split into a Shekau-loyal faction ("Jama'at Ahl al-sunna li-l-Da'wa wa-l-Jihad", generally known as "Boko Haram"), and a pro-IS faction led by Abu Musab al-Barnawi (which continued to call itself "Islamic State's West Africa Province"). These two groups have since clashed with each other, though they possibly occasionally cooperated against the local governments.[5][6][7] In addition, Shekau never officially renounced his pledge of allegiance to IS as a whole; his forces are thus occasionally regarded as "second branch of ISWAP". Overall, the relation of Shekau with IS remained confused and ambiguous.[10]

In the next years, Barnawi's ISWAP and Shekau's Boko Haram both reconsolidated, though ISWAP grew into the more powerful group. Whereas Shekau had about 1,000 to 2,000 fighters under his command by 2019, the Islamic State loyalists counted up to 5,000 troops.[11] It also changed its tactics, and attempted to win support by local civilians unlike Boko Haram which was known for its extensive indiscriminate violence. ISWAP begun to build up basic government services and focused its efforts on attacking Christian targets instead Muslim ones. However, the group also continued to attack humanitarian personnel and select Muslim communities.[2] In the course of the Chad Basin campaign (2018–2020), ISWAP had extensive territorial gains before losing many to counter-offensives by the local security forces. At the same time, it experienced a violent internal dispute which resulted in the deposition of Abu Musab al-Barnawi and the execution of several commanders.[12][13] In the course of 2020, the Nigerian Armed Forces repeatedly attempted to capture the Timbuktu Triangle[b] from ISWAP, but suffered heavy losses and made no progress.[15]

In April 2021, ISWAP overran a Nigerian Army base around Mainok, capturing armoured fighting vehicles including main battle tanks, as well as other military equipment.[16] In the next month, ISWAP attacked and overran Boko Haram's bases in the Sambisa Forest and Abubakar Shekau killed himself.[17] As a result, many Boko Haram fighters defected to ISWAP, and the group secured a chain of strongholds from Nigeria to Mali to southern Libya.[18][19] Despite this major victory, ISWAP was forced to deal with Boko Haram loyalists who continued to oppose the Islamic State.[20] In August 2021, Abu Musab al-Barnawi was reportedly killed, either in battle with the Nigerian Army or during inter-ISWAP clashes.[21][22] Later that month, ISWAP suffered a defeat when attacking Diffa,[23] but successfully raided Rann, destroying the local barracks before retreating with loot.[24] In October and November, there were further leadership changes in ISWAP, as senior commanders were killed by security forces.[25]

Organization[]

ISWAP's central command is subordinate to IS's core group headed by self-appointed Caliph Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi. Initially, ISWAP was headed by a single commander, termed the wali (governor). The group's first overall wali was Abubakar Shekau who was succeeded by Abu Musab al-Barnawi in 2016. The latter was replaced by Ba Idrisa in March 2019 who was in turn purged and executed in 2020.[26][27] He was replaced by Ba Lawan.[27] In general, the shura, a consultative assembly,[28] holds great power within the group. This has led researcher Jacob Zenn to argue that the shura gives the group an element of "democracy". The shura's influence has allowed ISWAP to expand its popular support, yet has also made it more prone to leadership struggles.[29] Appointments to leadership positions such as the shura or the governorships are discussed internally and by ISIL's core group; IS's core group also has to approve new appointments.[28]

In May 2021, the shura was temporarily dissolved and Abu Musab al-Barnawi was appointed "caretaker" leader of ISWAP.[30][31] By July 2021, the shura had been restored,[28] and ISWAP's internal system had been reformed.[28][32] The regional central command now consists of the Amirul Jaish (military leader) and the shura. There is no longer an overall wali, and the shura's head instead serves as leader of ISWAP's governorates, while the Amirul Jaish acts as chief military commander. "Sa'ad" served as new Amirul Jaish, while Abu Musab al-Barnawi became head of the shura.[28] However, non-IS sources still claim that a position referred to as the overall "wali" or "leader of ISWAP" continues to exist.[32][25][33] This position was reportedly filled by ex-chief wali Ba Lawan (also "Abba Gana")[32][33] before passing to Abu-Dawud (also "Aba Ibrahim"), Abu Musab al-Barnawi, Malam Bako, and Sani Shuwaram in a matter of months in late 2021.[25]

In March 2019,[26] IS's core group began to portray ISWAP as being responsible for all operations by pro-IS groups in West Africa. Accordingly, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (IS-GS) was formally put under ISWAP's command. ISWAP and IS-GS maintain logistical connections, but the former's actual influence on the latter is limited.[2][26]

In general, ISWAP is known to maintain substantial contacts with IS's core group,[28][34][35] although the exact extent of ties is debated among researchers.[2] ISWAP aligns ideologically with IS, and has also adopted many of its technologies and tactics. ISWAP uses suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices[34] and drones typical for IS. Researchers consider these as proof of support and advice by IS members from Syria and Iraq.[34][35] IS's core group has probably provided ISWAP with not just technical, but also financial aid.[2][3]

Known offices and leadership[]

| Office | Office-holders |

|---|---|

| Wali of ISWAP |

Note: The office of overall wali appeared to have been abolished by 2021,[28] but outside sources continue to claim that certain individuals are the "leader" or "wali" of ISWAP.[33][25] |

| Amirul Jaish |

|

| Head of the Shura | |

| Deputy (Naib) | |

| Chief Judge | |

| Chief Prosecutor |

|

| Wali of Tumbuma | |

| Wali of Timbuktu[b] | |

| Wali of Sambisa Forest |

|

| Wali of Lake Chad | |

| Ameer Fiya of Timbuktu |

|

| Ameer Fiya of Sambisa Forest | |

| Amir of Marte |

|

| Fitya of Marte |

|

| Chief Mechanic[41] |

|

Administration[]

In contrast to Boko Haram which mostly raided and enslaved civilians, ISWAP is known for setting up an administration in the territories where it is present.[2][42] As IS maintains to be a state despite having lost its territory in the Middle East, ISWAP's ability to run a basic government is ideologically important for all of IS.[1] Despite not fully controlling the areas where it is present,[43] ISWAP maintains more control over large swaths of the countryside than the Nigerian government[44] and has created four governorates.[42] These governorates, centered at Lake Chad, Sambisa Forest, Timbuktu,[b] and Tumbuma, are each headed by a wali and have their own governing structures. Each governorate has its own military commanders, and sends at least two representatives to ISWAP's shura.[28]

ISWAP collects taxes on agriculture and trade in its territories,[11][2] and offers protection as well as some "limited services" in return,[44] including law enforcement.[2] The group appoints its own police chiefs, and its police also enforces the hisbah.[41] The group makes considerable efforts to win local grassroots support,[18] and has employed a "hearts and minds" policy toward the local communities.[19] It encourages locals to live in de facto rebel-held communities.[44] Among its taxes, ISWAP also collects the zakat, a traditional Muslim tax and form of almsgiving which is used to provide for the poor. ISWAP's zakat has been featured in propaganda distributed by IS's newspaper, al-Naba.[1] ISWAP's "Zakat Office" is known to operate fairly systematically and effectively, raising substantial funds to support both ISWAP as well as local civilians. Experts Tricia Bacon and Jason Warner have described ISWAP's taxation system as being locally less corrupt and more fair than that of the Nigerian state; some local traders argue that ISWAP creates a better environment for trade in rice, fish, and dried pepper.[45] At the same time, ISWAP is known for targeting agencies providing humanitarian aid, thereby depriving locals of basic necessities in government-held areas.[44][2]

Military strength[]

ISWAP's strength has fluctuated over the years, and estimates accordingly vary. In 2017, researchers put its strength at around 5,000 militants.[46] By the next year, it was believed to have shrunk to circa 3,000.[47] The group experienced a surge and regained much poweress in 2019, resulting in researchers estimating that it had grown to 5,000 or up to 18,000 fighters.[11][48] By 2020, the United States Department of Defense publicly estimated that ISWAP had 3,500 to 5,000 fighters.[2]

ISWAP is known to employ inghimasi forlorn hope/suicide attack shock troops[49] as well as armoured fighting vehicles (AVFs).[50][51][52] Throughout its history, ISWAP has repeatedly seized tanks including T-55s,[16] VT-4s, ,[15] and armoured personnel carriers such as the BTR-4EN, and then pressed them into service.[16] The group also relies heavily on motorcycles, technicals, and captured military tactical/utility vehicles such as Kia KLTVs.[16]

Notes[]

- ^ Officially Wilāyat Garb Ifrīqīyā (Arabic: ولاية غرب أفريقيا), meaning "West African Province"

- ^ a b c A border area between Nigeria's Borno and Yobe states is known as the "Timbuktu Triangle".[14] The area is covered by the Alagarno forest.[15] The Timbuktu Triangle should not be confused with the city of Timbuktu in Mali.

References[]

- ^ a b c Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi (28 March 2021). "The Islamic State's Imposition of Zakat in West Africa". Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Boko Haram and the Islamic State's West Africa Province" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. 26 March 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ a b Bacon & Warner (2021), p. 80.

- ^ TRADOC G-2 (2015), pp. 2–5.

- ^ a b c Thomas Joscelyn; Caleb Weiss (17 January 2019). "Thousands flee Islamic State West Africa offensive in northeast Nigeria". Long War Journal. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi (5 August 2018). "The Islamic State West Africa Province vs. Abu Bakr Shekau: Full Text, Translation and Analysis". Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ a b Warner & Hulme (2018), pp. 21–22.

- ^ Jason Burke; Emmanuel Akinwotu (20 May 2021). "Boko Haram leader tried to kill himself during clash with rivals, officials claim". Guardian. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi (28 June 2021). "The Defeat of Abu Bakr Shekau's Group in Sambisa Forest". Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Warner & Hulme (2018), p. 22.

- ^ a b c Danielle Paquette (21 May 2021). "Is Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau dead this time? The Nigerian military is investigating". Washington Post. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ Bassim Al-Hussaini (3 March 2020). "New ISWAP boss slays five rebel leaders, silences clerical tones". Premium Times. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Zenn (2020), pp. 6–7.

- ^ "Nigeria Troops Overrun ISWAP Jihadist Camps in Northeast". Defense Post. 5 February 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Murtala Abdullahi (8 December 2020). "ISWAP Captures Newly Inducted Nigerian Army Armoured Vehicle". Humangle. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Boko Haram Releases Photos Of Newly Acquired Armoured Tanks, Operation Vehicles, Others Captured From Nigerian Army". Sahara Reporters. 28 April 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "ISWAP militant group says Nigeria's Boko Haram leader is dead". Reuters. 7 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b Jason Burke; Emmanuel Akinwotu (20 May 2021). "Boko Haram leader tried to kill himself during clash with rivals, officials claim". Guardian. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ a b Jason Burke (22 May 2021). "Rise of Isis means Boko Haram's decline is no cause for celebration". Guardian. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Abubakar Shekau's Boko Haram Faction Confirms Death Of Leader, Issues Fresh Threats". Sahara Reporters. 15 June 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Vicious ISWAP leader, Al-Barnawi, killed". Daily Trust. 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ "Notorious Boko Haram, Islamic State Leader, Al-Barnawi Killed In Borno". Sahara Reporters. 15 September 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ Maina Maina (26 August 2021). "7 soldiers, 43 terrorists killed as MNJTF battles Boko Haram, ISWAP in Diffa". Daily Post. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Wale Odunsi (1 September 2021). "Borno: ISWAP claims 10 Nigerian troops died in Rann attack". Daily Post. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wale Odunsi (6 November 2021). "ISIS crowns Sani Shuwaram as new ISWAP leader". Daily Post. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zenn (2020), p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Malik Samuel (13 July 2021). "Islamic State fortifies its position in the Lake Chad Basin". Institute for Security Studies. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- ^ Zenn (2020), p. 7.

- ^ Zenn (2021), p. 1.

- ^ Ahmad Salkida (21 May 2021). "What Shekau's Death Means For Security In Nigeria, Lake Chad". Humangle. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "ISWAP-Boko Haram Reshuffles 'Cabinet', Imposes Levies On Agricultural, Trade Activities In Nigerian Communities". Sahara Reporters. 4 July 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wale Odunsi (18 August 2021). "ISWAP reshuffles Nigerian leaders after ISIS order". Daily Post. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Jacob Zenn (10 December 2018). "Is Boko Haram's notorious leader about to return from the dead again?". African Arguments. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Islamic Militants' Deadly Resurgence Threatens Nigeria Polls". Voice of America. Associated Press. 12 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Wale Odunsi (21 September 2021). "Boko Haram appoints deputy leader as ISWAP redeploys commanders". Daily Post. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ a b c "Nigerian official says new leader of ISIL-linked group killed". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- ^ "After attack on rival, IS jihadists battle for control in northeast Nigeria". France24. 4 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Abdulkareem Haruna (13 January 2021). "Multinational forces 'kill top ISWAP commander'". Premium Times. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "ISWAP Fighters Arrest Shekau's Commanders, Meet with Surrendered Top Boko Haram Members". Sahara Reporters. 26 May 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Chaos as Boko Haram/ISWAP executes its own 'governor of Lake Chad' in power struggle". Reuben Abati Media. 28 July 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d Kunle Adebajo (21 May 2021). "How Did Abubakar Shekau Die? Here's What We Know So Far". Humangle. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ "Death of Boko Haram's leader spells trouble for Nigeria and its neighbors". DW. 8 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Dulue Mbachu (17 June 2021). "Death of Boko Haram leader doesn't end northeast Nigeria's humanitarian crisis". The New Humanitarian. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Bacon & Warner (2021), p. 81.

- ^ Warner & Hulme (2018), p. 23.

- ^ "Islamic Militants' Deadly Resurgence Threatens Nigeria Polls". Voice of America. Associated Press. 12 February 2019. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "IS Down But Still a Threat in Many Countries". Voice of America. 24 April 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ Fergus Kelly (10 April 2019). "Niger gendarmes killed and hostages taken in latest Islamic State attack in Diffa". Defense Post. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ James Reinl (19 April 2019). "How stolen weapons keep groups like Boko Haram in business". Public Radio International. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ "IS claims responsibility for Niger attack which killed 71: SITE". France24. 12 December 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ^ Joe Parkinson; Drew Hinshaw (12 December 2019). "Islamic State, Seeking Next Chapter, Makes Inroads Through West Africa". Retrieved 1 October 2020.

Works cited[]

- Bacon, Tricia; Warner, Jason (2021). "Twenty Years After 9/11: The Threat in Africa—The New Epicenter of Global Jihadi Terror" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center. 14 (7): 76–90.

- Warner, Jason; Hulme, Charlotte (2018). "The Islamic State in Africa: Estimating Fighter Numbers in Cells Across the Continent" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center. 11 (7): 21–28.

- TRADOC G-2 (2015). Threat Tactics Report: Boko Haram (PDF). Fort Eustis: United States Army Training and Doctrine Command.

- Zenn, Jacob (20 March 2020). "Islamic State in West Africa Province and the Battle With Boko Haram" (PDF). Terrorism Monitor. Jamestown Foundation. 18 (6): 6–8.

- Zenn, Jacob (24 May 2021). "Killing of Boko Haram Leader Abubakar Shekau Boosts Islamic State in Nigeria" (PDF). Terrorism Monitor. Jamestown Foundation. 19 (10): 1–2.

Further reading[]

- Warner, Jason; O'Farrell, Ryan; Nsaibia, Héni; Cummings, Ryan (2020). "Outlasting the Caliphate: The Evolution of the Islamic State Threat in Africa" (PDF). CTC Sentinel. West Point, New York: Combating Terrorism Center. 13 (11): 18–33.

- 2015 establishments in Nigeria

- Factions of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

- Boko Haram insurgency

- Islamic extremism in Northern Nigeria

- Islamic terrorism in Africa

- Islamic terrorism in Nigeria

- Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant in Nigeria

- Islamist groups

- Jihadist groups

- Rebel groups in Nigeria