James Miller McKim

James Miller McKim | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 10, 1810 Carlisle, Pennsylvania |

| Died | June 13, 1874 (aged 63) West Orange, New Jersey |

| Education | |

| Occupation | Clergyman |

| Spouse(s) | Sarah Allibone Speakman

(m. 1840) |

| Children | Charles Follen McKim |

James Miller McKim (November 10, 1810 – June 13, 1874) was a Presbyterian minister and abolitionist. He was also the father of the architect Charles Follen McKim.

Biography[]

McKim was born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and educated at Dickinson College and Princeton.[1] In 1835, he was ordained pastor of a Presbyterian church at Womelsdorf, Pennsylvania. A few years before, the perusal of a copy of Garrison's Thoughts on Colonization had made him an abolitionist. He was a member of the convention that formed the American Anti-slavery Society, and in October 1836 left the pulpit to lecture under its auspices for the cause of emancipation.[1] He delivered addresses throughout Pennsylvania. In 1840, he moved to Philadelphia to work for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society as lecturer, organizer, and corresponding secretary. The same year, he married Sarah Allibone Speakman.[1] At times, he served as the editor of the Pennsylvania Freeman.

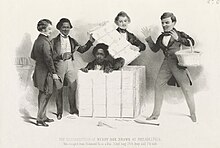

In 1849, he was on the receiving end of an unusual and historic shipment, when Henry "Box" Brown, an innovative and determined escaped slave from Richmond, Virginia, arrived in Philadelphia in a small shipping box and emerged into freedom. McKim was depicted in The Resurrection of Henry Box Brown at Philadelphia, a lithograph by artist Samuel W. Rowse, which was widely published to help raise funds for the Underground Railroad. Brown wrote his autobiography in 1851. McKim's labors frequently brought him in contact with the operations of the Underground Railroad, and he was often connected with the slave cases that came before the courts, especially after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850.

In 1859, Reverend McKim and his wife Sarah escorted Mary Brown, the wife of abolitionist John Brown, to Virginia, after his failed raid on Harpers Ferry. The McKims were accompanied in this effort by Hector Tyndale, another Philadelphia abolitionist. After visiting her husband in jail in Charlestown, Virginia [today Charles Town, West Virginia], Mary Brown, along with the McKims and Tyndale, stayed in Harpers Ferry until after the John Brown's execution on December 2, 1859. The McKims prayed and held hands with Mary Brown until the hour of execution passed. Afterward, they assisted her in claiming Brown's body and escorted her to Philadelphia; McKim continued with her to his burial place, the John Brown Farm in remote North Elba, New York, near present-day Lake Placid.

In the winter of 1862, immediately after the capture of Port Royal, South Carolina, he was instrumental in calling a public meeting of the citizens of Philadelphia to consider and provide for the wants of the 10,000 slaves that had been suddenly liberated. One of the results of this meeting was the organization of the Philadelphia . He afterward became an earnest advocate of the enlistment of colored troops, and as a member of the Union League aided in the establishment of Camp William Penn, and the recruiting of eleven regiments. In November 1863, the Port Royal Relief Committee was enlarged into the Pennsylvania , and McKim was made its corresponding secretary.[1]

As the Civil War dragged on, and, after President Lincoln announced the emancipation of the slaves in the South in 1863, McKim joined the and provided valuable services to that body.

He travelled extensively, and labored diligently to establish schools in the South. In 1865, he joined the and used every effort to promote general and impartial education in the South. In July 1869, the Commission, having accomplished all that seemed possible at the time, decided unanimously, on McKim's motion, to disband.[1]

His health having meantime become greatly impaired, he soon afterward retired from public life. In 1865 he assisted in founding The Nation of New York. McKim saw the publication as a way of continuing the work of the abolitionist movement.[2] He died in West Orange, New Jersey.[3]

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Brown, John Howard, ed. (1903). Lamb's Biographical Dictionary of the United States. 5. James H. Lamb Company. p. 271. Retrieved July 30, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "According to Nation historian Richard Clark Sterne, it was James Miller McKim...who was particularly attuned to the need for a publication that sustained the abolitionist spirit after the Civil War." Paula Giddings, "Introduction" to Burning All Lllusions: writings from the nation on race, 1866-2002. New York, Thunder's Mouth Press and Nation Books, 2002. ISBN 1560253843 (p.3)

- ^ "Obituary". Chicago Tribune. June 14, 1874. p. 16. Retrieved July 30, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

References[]

Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

External links[]

- 1810 births

- 1874 deaths

- American abolitionists

- People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War

- People from Carlisle, Pennsylvania

- Dickinson College alumni

- American Presbyterian ministers

- Presbyterian abolitionists

- Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania

- 19th-century American clergy