James V of Scotland

| James V | |

|---|---|

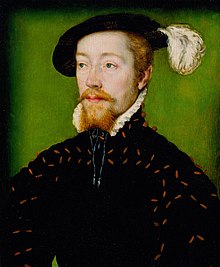

Portrait of James aged around 25, by Corneille de Lyon | |

| King of Scotland | |

| Reign | 9 September 1513 – 14 December 1542 |

| Coronation | 21 September 1513 |

| Predecessor | James IV |

| Successor | Mary |

| Born | 10 April 1512 Linlithgow Palace, Linlithgow, Scotland |

| Died | 14 December 1542 (aged 30) Falkland Palace, Fife, Scotland |

| Burial | January 1543 |

| Spouse | Madeleine of France

(m. 1537; died 1537)Mary of Guise (m. 1538) |

| Issue more... |

|

| House | Stewart |

| Father | James IV of Scotland |

| Mother | Margaret of England |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542, which followed the Scottish defeat at the Battle of Solway Moss. His only surviving legitimate child, Mary, Queen of Scots, succeeded him when she was just six days old.

Early life[]

James was the third son of King James IV of Scotland and his wife Margaret Tudor, a daughter of Henry VII of England and sister of Henry VIII, and was the only legitimate child of James IV to survive infancy. He was born on 10 April 1512 at Linlithgow Palace, Linlithgowshire, and baptized the following day,[1] receiving the titles Duke of Rothesay and Prince and Great Steward of Scotland.[2] He became king at just seventeen months old when his father was killed at the Battle of Flodden on 9 September 1513.

James was crowned in the Chapel Royal at Stirling Castle on 21 September 1513. During his childhood, the country was ruled by regents, first by his mother, until she remarried the following year, and then by John Stewart, 2nd Duke of Albany, next in line to the Crown after James and his younger brother Alexander Stewart, Duke of Ross, who died in infancy. Other regents included Robert Maxwell, 5th Lord Maxwell, a member of the Council of Regency who was also bestowed as Regent of Arran, the largest island in the Firth of Clyde. In February 1517, James came from Stirling to Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, but during an outbreak of plague in the city, he was moved to the care of Antoine d'Arces at nearby rural Craigmillar Castle.[3] At Stirling, the 10-year-old James had a guard of 20 footmen dressed in his colours, red and yellow. When he went to the park below the Castle, "by secret and in right fair and soft wedder (weather)," six horsemen would scour the countryside two miles roundabout for intruders.[4] Poets wrote their own nursery rhymes for James and advised him on royal behavior. As a youth, his education was in the care of Sir David Lyndsay.[5] William Stewart, in his poem Princelie Majestie, written in Middle Scots, counselled James against ice-skating:

To princes als it is ane vyce,

To ryd or run over rakleslie,

Or aventure to go on yce,

Accordis nocht to thy majestie.[6]

In the autumn of 1524, at the age of 12, James dismissed his regents and was proclaimed an adult ruler by his mother. Several new court servants were appointed including a trumpeter, Henry Rudeman.[7] Thomas Magnus, the English diplomat, gave an impression of the new Scottish court at Holyroodhouse on All Saints' Day 1524: "trumpets and shamulles did sounde and blewe up mooste pleasauntely." Magnus saw the young king singing, playing with a spear at Leith, and with his horses, and he was given the impression that the king preferred English manners over French fashions.[8]

In 1525 Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of Angus, the young king's stepfather, took custody of James and virtually held him prisoner for three years, exercising power on his behalf. Several attempts were made to free the young King – one by Walter Scott of Branxholme and Buccleuch, who ambushed the King's forces on 25 July 1526 at the Battle of Melrose and was routed off the field. Another attempt later that year, on 4 September at the Battle of Linlithgow Bridge, failed again to relieve the King from the clutches of Angus. When James and his mother came to Edinburgh on 20 November 1526, she stayed in the chambers at Holyroodhouse, which Albany had used, James using the rooms above.[9] In February 1527, Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond, gave James twenty hunting hounds and a huntsman. Magnus thought the Scottish servant sent to Sheriff Hutton Castle for the dogs was intended to note the form and fashion of the Duke's household for emulation in Scotland.[10] James finally escaped from Angus's care in 1528 and assumed the reins of government himself.

Reign and religion[]

The first action James took as king was to remove Angus from the scene. The Douglas family – excluding James's half-sister Margaret, who was already safely in England – were forced into exile and James besieged their castle at Tantallon. He then subdued the Border rebels and the chiefs of the Western Isles. As well as taking advice from his nobility and using the services of the Duke of Albany in France and at Rome, James had a team of professional lawyers and diplomats, including Adam Otterburn and Thomas Erskine of Haltoun. Even his pursemaster and yeoman of the wardrobe, John Tennent of Listonschiels, was sent on an errand to England, though he got a frosty reception.[11]

James increased his income by tightening control over royal estates and from the profits of justice, customs and feudal rights. He also gave his illegitimate sons lucrative benefices, diverting substantial church wealth into his coffers. James spent a large amount of his wealth on building work at Stirling Castle, Falkland Palace, Linlithgow Palace and Holyrood, and he built up a collection of tapestries from those inherited from his father.[12] James sailed to France for his first marriage and strengthened the royal fleet. In 1540, he sailed to Kirkwall in Orkney, then Lewis, in his ship the Salamander, first making a will in Leith, knowing this to be "uncertane aventuris." The purpose of this voyage was to show the royal presence and hold regional courts, called "justice ayres."[13]

Domestic and international policy was affected by the Reformation, especially after Henry VIII broke from the Catholic Church. James V did not tolerate heresy, and during his reign a number of outspoken Protestants were persecuted. The most famous of these was Patrick Hamilton, who was burned at the stake as a heretic at St Andrews in 1528. Later in the reign, the English ambassador Ralph Sadler tried to encourage James to close the monasteries and take their revenue so that he would not have to keep sheep like a mean subject. James replied that he had no sheep, he could depend on his god-father the King of France, and it was against reason to close the abbeys that "stand these many years, and God's service maintained and kept in the same, and I might have anything I require of them."[14] Sadler knew that James did farm sheep on his estates.[15]

James recovered money from the church by getting Pope Clement VII to allow him to tax monastic incomes.[16] He sent £50 to Johann Cochlaeus, a German opponent of Martin Luther, after receiving one of his books in 1534.[17] On 19 January 1537, Pope Paul III sent James a blessed sword and hat symbolising his prayers that James would be strengthened against heresies from across the border.[18] These gifts were delivered by the Pope's messenger while James was at Compiègne in France on 25 February 1537.[19]

According to 16th-century writers, his treasurer James Kirkcaldy of Grange tried to persuade James against the persecution of Protestants and to meet Henry VIII at York.[20] James and Henry corresponded about meeting in 1536. Pope Paul III advised James against travelling to England, and sent an envoy or nuncio to Scotland to discuss the initiative.[21] Although Henry VIII sent his tapestries to York in September 1541 ahead of a meeting, James did not come. The lack of commitment to this meeting was regarded by English observers as a sign that Scotland was firmly allied to France and Catholicism, particularly by the influence of Cardinal Beaton, Keeper of the Privy Seal, and as a cause for war.[22]

In a July 1541 communication with Irish chiefs, James assumed the style of "Lord of Ireland" (dominus Hiberniae), as a further challenge to Henry VIII, lately created King of Ireland.[23]

Marriages[]

As early as August 1517, a clause of the Treaty of Rouen provided that if the Auld Alliance between France and Scotland was maintained, James should have a French royal bride. Yet the daughters of Francis I of France were promised elsewhere or sickly.[24] Perhaps to remind Francis of his obligations, James's envoys began negotiations for his marriage elsewhere from the summer of 1529, both to Catherine de' Medici, the Duchess of Urbino, and Mary of Austria, Queen of Hungary, the sister of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. The English diplomat Thomas Magnus raised the possibility of his marriage to Princess Mary with Adam Otterburn in December 1528.[25] But plans changed. In February 1533, two French ambassadors, Guillaume du Bellay, sieur de Langes, and Etienne de Laigue, sieur de Beauvais, who had just been in Scotland, told the Venetian ambassador in London that James was thinking of marrying Christina of Denmark.[26] Marguerite d'Angoulême, sister of Francis I, suggested her sister-in-law Isabella, who was the same age.

Francis I insisted that his daughter Madeleine's health was too poor for marriage. Eventually, on 6 March 1536, a contract was made for James V to marry Mary of Bourbon, daughter of the Duke of Vendôme. She would have a dowry as if she were a French Princess. Francis sent a courtier, Guillaume d'Yzernay, to the Earl of Moray, with the collar and insignia of the Order of Saint Michael to give to James V as a token of his affection and their family union.[27]

James decided to visit France in person. He sailed from Kirkcaldy on 1 September 1536, with the Earl of Argyll, the Earl of Rothes, Lord Fleming, David Beaton, the Prior of Pittenweem, the Laird of Drumlanrig and 500 others, using the Mary Willoughby as his flagship.[28] First he visited Mary of Bourbon at St. Quentin in Picardy, but then went south to meet King Francis I.[29] During his stay in France, in October 1536, James went boar-hunting at Loches with Francis, his son the Dauphin, the King of Navarre and Ippolito II d'Este.[30]

James renewed the Auld Alliance and fulfilled the 1517 Treaty of Rouen on 1 January 1537 by marrying Madeleine of Valois, the king's daughter, in Notre Dame de Paris. The wedding was a great event: Francis I made a contract with six painters for the splendid decorations, and there were days of jousting at the Louvre Palace.[31] At his entry to Paris, James wore a coat described as "sad cramasy velvet slashed all over with gold cut out on plain cloth of gold fringed with gold and all cut out, knit with horns and lined with red taffeta."[32] James V so liked red clothing that, during the wedding festivities, he upset the city dignitaries who had sole right to wear that colour in processions. They noted he could not speak a word of French.[33]

James and Madeleine returned from France on 19 May 1537, arriving at Leith, the king's Scottish fleet accompanied with ten great French ships.[34] As the couple sailed northwards, some Englishmen had come aboard off Bridlington and Scarborough. While the fleet was off Bamburgh on 15 May, three English fishing boats supplied fish, and the King's butcher landed in Northumbria to buy meat.[35] The English border authorities were dismayed by this activity.[36]

Madeleine did not enjoy good health. In fact, she was consumptive and died soon after arrival in Scotland in July 1537. Spies told Thomas Clifford, the Captain of Berwick, that James omitted "all manner of pastime and pleasure", but continually oversaw the maintenance of his guns, going twice a week secretly to Dunbar Castle with six companions.[37] James then proceeded to marry Mary of Guise, daughter of Claude, Duke of Guise, and widow of Louis II d'Orléans, Duke of Longueville, by proxy on 12 June 1538. Mary already had two sons from her first marriage, and the union produced two sons. However, both died in April 1541, just eight days after baby Robert was baptised. Their daughter and James's only surviving legitimate child, Mary, was born in 1542 at Linlithgow Palace.

Outside interests[]

According to legend, James was nicknamed "King of the Commons" as he would sometimes travel around Scotland disguised as a common man, describing himself as the "Gudeman of Ballengeich" ('Gudeman' means 'landlord' or 'farmer', and 'Ballengeich' was the nickname of a road next to Stirling Castle – meaning 'windy pass' in Gaelic[38]). James was also a keen lute player.[39] In 1562 Sir Thomas Wood reported that James had "a singular good ear and could sing that he had never seen before" (sight-read), but his voice was "rawky" and "harske." At court, James maintained a band of Italian musicians who adopted the name Drummond. These were joined for the winter of 1529/30 by a musician and diplomat sent by the Duke of Milan, Thomas de Averencia de Brescia, probably a lutenist.[40] The historian Andrea Thomas makes a useful distinction between the loud music provided at ceremonies and processionals and instruments employed for more private occasions or worship, the music fyne described by Helena Mennie Shire. This quieter music included a consort of viols played by four Frenchmen led by Jacques Columbell.[41] It seems certain that David Peebles wrote music for James V and probable that the Scottish composer Robert Carver was in royal employ, though evidence is lacking.[42]

As a patron of poets and authors, James supported William Stewart and John Bellenden, the son of his nurse, who translated the Latin History of Scotland compiled in 1527 by Hector Boece into verse and prose.[43] Sir David Lindsay of the Mount, the Lord Lyon, head of the Lyon Court and diplomat, was a prolific poet. He produced an interlude at Linlithgow Palace thought to be a version of his play The Thrie Estaitis in 1540. James also attracted the attention of international authors. The French poet Pierre de Ronsard, who had been a page of Madeleine of Valois, offered unqualified praise;

"Son port estoit royal, son regard vigoureux

De vertus, et de l'honneur, et guerre amoureux

La douceur et la force illustroient son visage

Si que Venus et Mars en avoient fait partage"

His royal bearing, and vigorous pursuit

of virtue, of honour, and love's war,

this sweetness and strength illuminate his face,

James was a poet himself; his works include "The Gaberlunzieman" and "The Jolly Beggar"[46]

When he married Mary of Guise, Giovanni Ferrerio, an Italian scholar who had been at Kinloss Abbey in Scotland, dedicated to the couple a new edition of his work On the True Significance of Comets against the Vanity of Astrologers.[47] Like Henry VIII, James employed many foreign artisans and craftsmen in order to enhance the prestige of his renaissance court.[48] Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie listed their professions;

he plenished the country with all kind of craftsmen out of other countries, as French-men, Spaniards, Dutch men, and Englishmen, which were all cunning craftsmen, every man for his own hand. Some were gunners, wrights, carvers, painters, masons, smiths, harness-makers (armourers), tapesters, broudsters, taylors, cunning chirugeons, apothecaries, with all other kind of craftsmen to apparel his palaces.[49]

One technological initiative was a special mill for polishing armour at Holyroodhouse next to his mint. The mill had a pole drive 32 feet long powered by horses.[50] Mary of Guise's mother Antoinette of Bourbon sent him an armourer. The armourer made steel plates for his jousting saddles in October 1538 and delivered a skirt of plate armour in February 1540. In the same year, for his wife's coronation, the treasurer's accounts record that James personally devised fireworks made by his master gunners. His goldsmith John Mosman renovated the crown jewels for the occasion.[51] When James took steps to suppress the circulation of slanderous ballads and rhymes against Henry VIII, Henry sent Fulke ap Powell, Lancaster Herald, to give thanks and to make arrangements for the present of a lion for James's menagerie of exotic pets.[52]

War with England[]

| Royal styles of James V | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Grace |

| Spoken style | Your Grace |

| Alternative style | Schir (sire)[53] |

The death of James's mother in 1541 removed any incentive for peace with England, and war broke out. Initially, the Scots won a victory at the Battle of Haddon Rig in August 1542. The Imperial ambassador in London, Eustace Chapuys, wrote on 2 October that the Scottish ambassadors ruled out a conciliatory meeting between James and Henry VIII in England until the pregnant Mary of Guise delivered her child. Henry would not accept this condition and mobilised his army against Scotland.[54]

James was with his army at Lauder on 31 October 1542. Although he hoped to invade England, his nobles were reluctant.[55] He returned to Edinburgh, on the way writing a letter in French to his wife from Falahill mentioning he had three days of illness.[56] The next month his army suffered a serious defeat at the Battle of Solway Moss. He took ill shortly after this, on 6 December; by some accounts this was a nervous collapse caused by the defeat, and he may have died from the grief, although some historians consider that it may just have been an ordinary fever. John Knox later described his final movements in Fife.[57]

Whatever the cause of his illness, James was on his deathbed at Falkland Palace when his only surviving legitimate child, a girl, was born. Sir George Douglas of Pittendreich brought the news of the king's death to Berwick. He said James died at midnight on Thursday 14 December; the king was talking but delirious and spoke no "wise words." According to George Douglas, James in his delirium lamented the capture of his banner and Oliver Sinclair at Solway Moss more than his other losses.[58] An English chronicler suggested another cause of the king's grief was his discomfort on hearing of the murder of the English Somerset Herald, Thomas Trahern, at Dunbar.[59] James died at Falkland Palace but was buried at Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh with his first wife Queen Madeleine.[60]

Before he died, he is reported to have said "it cam wi a lass, it'll gang wi a lass" (meaning "It began with a girl and it will end with a girl").[61] This could refer to the Stewart dynasty's accession to the throne through Marjorie Bruce, daughter of Robert the Bruce. The prophecy could have been intended to express his belief that his new-born daughter Mary would be the last of the Stewart monarchs. In fact, the last Stewart monarch in Britain was female: Anne, Queen of Great Britain (d. 1714).

The Earl of Arran and Cardinal Beaton ordered his wardrobe servant John Tennent to give items of his clothing and armour to their supporters and allies. The king's former lawyer Adam Otterburn was given an armoured doublet called a jack of plate.[62]

Aftermath[]

James was succeeded by his infant daughter Mary. He was buried at Holyrood Abbey alongside his first wife Madeleine and his two sons in January 1543. David Lindsay supervised the construction of his tomb. One of his French artists, Andrew Mansioun, carved a lion and an inscription in Roman letters measuring eighteen feet. The tomb was destroyed in the sixteenth century, according to William Drummond of Hawthornden as early as 1544, by the English during the burning of Edinburgh.[63] Scotland was ruled by Regent Arran and was soon drawn into the war of the Rough Wooing.

Issue[]

By Madeleine of France

- no issue

By Mary of Guise

- James, Duke of Rothesay (22 May 1540, St Andrews, Fife – 21 April 1541).

- Arthur[64] or Robert, Duke of Albany (12 April 1541, Falkland Palace – 20 April 1541), buried in Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh.[65]

- Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542, Linlithgow Palace – 8 February 1587; had issue).

Additionally, James V had nine known illegitimate children, at least three of whom were fathered before the age of 20.[citation needed] The young King was said to have been encouraged in his amorous affairs by the Angus regime to keep him distracted from politics.[66] In addition to these aristocratic liaisons, David Lindsay described the king's other affairs in his poem, The Answer to the Kingis Flyting; 'ye be now strang lyke ane elephand, And in till Venus werkis maist vailyeand.'[67]

The treasurer's accounts include some expenses for the upbringing of these children. In April 1532 the nurse of Elizabeth Schaw's son was paid and another woman was rewarded for fostering another son.[68] Many of the sons of his aristocratic mistresses entered ecclesiastical careers. Pope Clement VII sent a dispensation to James V dated 30 August 1534 that allowed four of the children to take holy orders when they came of age. The document stated that James elder was in his fifth year, James younger and John in their third year, and Robert in his first year.[69]

- Adam Stewart (d. 20 June 1575), son of Lady Elizabeth Stewart,[70] (daughter of John Stewart, 3rd Earl of Lennox).

prior of Charterhouse, Perth, buried at St. Magnus, Kirkwall, Orkney; tombstone survives.[71] - James Stewart, son of Christine Barclay.

- Jean Stewart (d. 7 January 1588), daughter of Elizabeth Bethune, married Archibald Campbell, 5th Earl of Argyll, in 1553; divorced in 1573 due to desertion.

- James Stewart (c. 1531[72]–57), son of Elizabeth Shaw, Commendator of Kelso and Melrose.

- John Stewart, Lord Darnley and Prior of Coldingham (c. 1531 – November 1563), son of Elizabeth Carmichael (1514–1550) who later married John Somerville of Cambusnethan.[73] He married Jean (or Jane) Hepburn, sister and heiress of James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell; their son Francis Stewart became Earl of Bothwell, and a daughter Christine Stewart was appointed to rock the cradle of Prince James in March 1568.[74] He also had a son Hercules Stewart by an unknown mother.

- James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray (c. 1531 – 23 January 1570), son of Margaret Erskine, James's favourite mistress. He was Prior of St Andrews, advisor and rival to his half-sister Mary, Queen of Scots, and regent for his nephew, James VI.

- Robert Stewart, 1st Earl of Orkney (1533 – 4 February 1593), son of Euphame Elphinstone, Prior and Commendator of Holyrood Abbey.

- Robert Stewart, junior (d. 1581), second son of Margaret Erskine, Prior of Whithorn.[75]

Fictional portrayals[]

James V has been depicted in historical novels, poems, short stories, and one notable opera. They include the following:[76]

- Scott, Sir Walter, The Lady of the Lake, a Romantic narrative poem published in 1810 set in the Trossachs. He appears in disguise. The poem was tremendously influential in the nineteenth century and inspired the Highland Revival. James also features in Scott's Tales of a Grandfather.

- "Johnnie Armstrong", a traditional ballad relating the story of Scottish raider and folk-hero Johnnie Armstrong of Gilnockie, who was captured and hanged by King James V in 1530.

- Gioachino Rossini, La Donna del Lago (1819), an opera based on Scott's poem. Sung in Italian, James V appears as "Giacomo V".

- Gibbon, Charles (1881), The Braes of Yarrow. The novels features Scotland in the aftermath of the Battle of Flodden, covering events to 1514. Margaret Tudor, "Boy-King" James V, and Archibald Douglas, 5th Earl of Angus, are prominently featured.[77]

- Barr, Robert (1902), A Prince of Good Fellows. James is the titular Prince and the main character. He is depicted as an "adventure-loving persona".[76]

- Gunn, John (1913), The Fight at Summerdale. The novel depicts Orkney, Edinburgh and Normandy in the 16th century. James V "appears more than once" in the various chapters.[76]

- Knipe, John (1921), The Hour Before the Dawn. Depicts events "just before" and "after" the death of James V. James V, Mary of Guise and David Beaton are prominently depicted.[76]

Ancestors[]

| showAncestors of James V of Scotland |

|---|

References[]

- ^ Robert Kerr Hannay, Letters of James IV (SHS: Edinburgh, 1953), p. 243.

- ^ Mackay, Æneas (1892). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 29. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 153–161.

- ^ Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 5, p. 130.

- ^ HMC Earl of Mar & Kellie at Alloa House (London, 1904), pp. 11–2.

- ^ Kemp, David (12 January 1992). The Pleasures and Treasures of Britain: A Discerning Traveller's Companion. Dundurn 1992. ISBN 9781554883479. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

Sir David Lyndsay..was at the University (of St Andrews) and was....involved in the education of James V... many of his poems contain advice for the young king...

- ^ Craigie, W. A. ed., Maitland Folio Manuscript (STS: Edinburgh, 1919), p. 247.

- ^ A. Thomas, Princelie Majestie, (Edinburgh 2005), pp. 32–33: Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland, vol. 1 (Edinburgh 1908), pp. 492–4 nos. 3267–3282.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 4 part 4 (1836), 209, Magnus & Radclyff to Wolsey, 2 November 1524: cf. Letters & Papers Henry VIII, vol. 4 (London, 1875), no. 830.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 4 part 4 (1836), 460, Christopher Dacre to Lord Dacre.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 4 part 4 (1836), 464–5, Magnus to Wolsey 14 February 1527: Letters & Papers Henry VIII, vol. 4 (1875), no. 2885

- ^ Thomas, Andrea, Princelie Majestie (John Donald: Edinburgh, 2005), 12–15, 36: Murray, Atholl, 'Pursemaster's Accounts', Miscellany of the Scottish History Society, vol. 10 (SHS: Edinburgh, 1965), pp. 13–51.

- ^ Dunbar, John G., Scottish Royal Palaces (Tuckwell: East Linton, 1999).

- ^ HMC Mar & Kellie (London, 1904), 15, Will 12 June 1540: Cameron, Jamie, James V (Tuckwell: East Linton, 1998), pp. 245–248.

- ^ Clifford, Arthur ed., Sadler State Papers, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1809), p. 30.

- ^ Amongst references to the royal sheep, after James's death 600 were given to James Douglass of Drumlanrig), HMC 15th Report: Duke of Buccleuch (London, 1897), p. 17.

- ^ Cameron, Jamie, James V (Tuckwell, 1998), p. 260.

- ^ Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 6 (Edinburgh, 1905), p. 236.

- ^ Hay, Denys, ed., Letters of James V ( (HMSO: Edinburgh, 1954), 328:Reid, John J., 'The Scottish Regalia', PSAS, 9 December (1889), 28: this sword is lost.

- ^ Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 7 (Edinburgh, 1907), p. 18.

- ^ Steuart, A. Francis, ed., Memoirs of Sir James Melville of Halhill (Routledge, 1929), pp. 14–17.

- ^ Denys Hay, Letters of James V (Edinburgh, 1954), p. 320.

- ^ Campbell, Thomas P., Henry VIII and the Art of Majesty, Tapestries at the Tudor Court (Yale, 2007), p. 261.

- ^ Thomas D'Arcy McGee (1862), A Popular History of Ireland: from the Earliest Period to the Emancipation of the Catholics, Book VII, Chapter III.

- ^ Hay, Denys, Letters of James V (HMSO, 1954), pp. 51–52.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 4 part IV (London, 1836), p. 545.

- ^ Calendar of State Papers Venice, vol. 4 (London, 1871), no.861.

- ^ Denys Hay, Letters of James V (Edinburgh, 1954), p. 318.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 5 part 4 cont. (London, 1836), pp. 59–60.

- ^ Cameron, Jamie, James V (Tuckwell: East Linton, 1998), p. 131.

- ^ Hollingsworth, Mary, The Cardinal's Hat (Profile Books, 2004), p. 117.

- ^ Leproux, Guy-Michel, La peinture à Paris sous le règne de François Ier, Sorbonne (2001), p. 26.

- ^ Robertson, Joseph, Inventaires de la Royne d'Ecosse (Bannatyne Club, 1863), pp. xii–xiii, citing Thomson, Collection of Royal Inventories (Edinburgh, 1815), pp. 80–1.

- ^ Teulet, Piéces et documents inédits relatifs a l'histoire d'Ècosse (Bannatyne Club, 1852), pp. 122–5.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 5 part 4 cont., (1836), 79, Clifford to Henry VIII.

- ^ Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer, vol. 7 (Edinburgh, 1907), p. 24.

- ^ Letters & Papers Henry VIII, vol. 12 part 1 (London, 1890), nos. 1237–8, 1256, 1286, 1307.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 5 part IV cont., (London, 1836) pp. 94–95.

- ^ Black (1861), Picturesque Tourist of Scotland, pp. 180–1.

- ^ "The Court of Mary, Queen of Scots". BBC Radio 3. 28 February 2010.

- ^ Hay, Denys, ed., Letters of James V (HMSO, 1954), pp. 63, 169, 170: Shire, Helena M., in Stewart Style (Tuckwell: East Linton, 1996), pp. 129–133.

- ^ Thomas, Andrea, Princelie Majestie (John Donald, 2005), pp. 92–4, 98: H. M. Shire, Song Dance and Poetry (Cambridge, 1969).

- ^ Thomas, Andrea, Princelie Majestie (John Donald, 1998), pp. 105–7.

- ^ Van Heijnsbergen, Theo, 'Literature in Queen Mary's Edinburgh: the Bannatyne Manuscript', in The Renaissance in Scotland (Brill, 1994), pp. 191–6.

- ^ Bingham, Caroline, James V (Collins, 1971), p. 12, verse quoted from William Drummond of Hawthornden, History of the 5 Jameses (1655), pp. 348–9

- ^ Drummond of Hawthorden, William, Works, Edinburgh (1711), p. 115.

- ^ George, Eyre-Todd (1892). Scottish Poetry of the Sixteenth Century. Glasgow: W. Hodge and Co. pp. 139...182.

- ^ Ferrerio, Giovanni, De vera cometae significatione contra astrologorum omnium vanitatem. Libellus, nuper natus et aeditus, Paris , Vascovan, (1538).

- ^ Thomas, Andrea, Princelie Majestie, the court of James V (John Donald: Edinburgh, 2005), pp. 226–243.

- ^ Lindsay of Pitscottie, Robert, The History of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1778), p. 238: abbreviated in Lindsay of Pitscottie, vol. 2 (Edinburgh, 1814), p. 359.

- ^ Accounts of the Masters of Work, vol. 1 (HMSO: Edinburgh, 1957), pp. 101–102, 242 290: Thomas Andrea, Princelie Majestie (John Donald, 2005), p. 173.

- ^ Accounts of the Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 7 (Edinburgh, 1907), 95, 287 (taslet), 357 fireworks: Marguerite Wood, Balcarres Papers, vol. 1 (SHS: Edinburgh, 1923), pp. 18, 20.

- ^ Letters & Papers Henry VIII, vol. 14 part 1 (London, 1894), xix, no. 406: vol. 14 part 2 (London, 1895), no. 781.

- ^ David Lyndsay, 'Dreme,' line 1037, in Hamer, ed., Works of David Lindsay, STS (1931)

- ^ Calendar State Papers Spanish: 1542–1543, vol. 6 part 2, London (1895), p. 144, no.66.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol.5 part 4 part 2, (1836), 213: Laing, David, ed., The Works of John Knox, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1846) pp. 389–391.

- ^ Strickland, Agnes, Lives of the queens of Scotland and English princesses, vol. 1, Blackwood (1850), 402 part translated only; now preserved as National Archives of Scotland SP13/27.

- ^ Knox, John, "from History of the Reformation, book 2". Archived from the original on 29 August 2009.

- ^ Bain, JS., ed., The Hamilton Papers, vol. 1, Edinburgh, (1890) 336–339.

- ^ Grafton's Chronicle, vol. ii, London (1809), 488.

- ^ Collection of Epitaphs and Monumental Inscriptions: Chiefly in Scotland

- ^ Tudors (The History of England Volume 2) by Peter Ackroyd. Pan Books ISBN 9781447236818

- ^ Harrison, John G., Wardrobe Inventories of James V (Kirkdale Archaeology/Historic Scotland, 2008), pp. 6, 45 citing BL MC Royal 18 C f.210.

- ^ Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 8 (1908) 142–143: Works of Drummond of Hawthornden: History of the Five Jameses, (Edinburgh 1711), p. 116

- ^ The Scots Peerage, vol. 1, p. 155.

- ^ Weir, Alison (1996) Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy. London: Random House. ISBN 0-7126-7448-9, page 242

- ^ Thomas, Andrea, 'Women at the Court of James V' in Ewan & Meikle ed., Women in Scotland, c.1100-c.1750 (Tuckwell, 1999), p. 86.

- ^ Williams, Janet Hadley ed., Sir David Lyndsay, Selected Poems, Glasgow (2000), 98–100, 257–9.

- ^ James Balfour Paul, Accounts of the Treasurer, vol. 6 (Edinburgh, 1906), p. 40.

- ^ HMC: 6th Report & Appendix (London, 1877), p. 670.

- ^ Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ Clouston, J Storer (1919). "Some further early Orkney armorials" (PDF). PSAS. UK: AHDS. p. 186..

- ^ HMC: 6th Report & Appendix, (1877), p.670

- ^ Lee, Sidney, ed. (1898). "Stewart, John (1531-1563)". Dictionary of National Biography. 54. London: Smith, Elder & Co.: James Somerville, Memorie of the Somervilles, vol.1 (1815), pp.385–9, has 'Katherine' Carmichael.

- ^ HMC Mar & Kellie, vol. 1 (London, 1904), p. 18.

- ^ Gordon Donaldson, Register of the Privy Seal of Scotland: 1567-1574, vol. 6 (Edinburgh, 1963), p. 67 no. 298: Register of the Privy Seal, vol. 8 (Edinburgh, 1982), p. 485, no. 2742.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Nield (1968), p. 70

- ^ Nield (1968), p. 67

Sources[]

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "James V". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "James V". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

- Bingham, Caroline (1971), James V King of Scots, London: Collins, ISBN 0-00-211390-2

- Cameron, Jamie (1998), Macdougall, Norman (ed.), James V: The Personal Rule, 1528–1542, The Stewart Dynasty in Scotland, East Linton: Tuckwell Press, ISBN 978-1-86232-015-4

- Dawson, Jane (2007), Scotland Reformed 1488–1587, The New Edinburgh History of Scotland, 6, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-1455-4

- Donaldson, Gordon (1965), Scotland: James V to James VII, The Edinburgh History of Scotland, III, Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, ISBN 978-0-901824-85-1

- Dunbar, John (1999). Scottish Royal Palaces. Tuckwell Press. ISBN 1-86232-042-X.

- Ellis, Henry, 'A Household book of James V', in Archaeologia, vol. 22, (1829), 1–12

- Thomas, Andrea (2005), Princelie Majestie: The Court of James V of Scotland, Edinburgh: John Donald, ISBN 0-85976-611-X

- Hadley Williams, Janet (1996), Stewart Style 1513–1542, Edinburgh: Tuckwell Press, ISBN 1-898410-82-8

- Hadley Williams, Janet (2000), Sir David Lyndsay, Selected Poems, Glasgow: ASLS, ISBN 0-948877-46-4

- Harrison, John G. (2008). Wardrobe Inventories of James V: British Library MS Royal 18 C (PDF). Historic Scotland.

- Nield, Jonathan (1968), A Guide to the Best Historical Novels and Tales, Ayer Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8337-2509-7

- Wormald, Jenny (1981), Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland 1470–1625, The New History of Scotland, 4, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0-7486-0276-3

External links[]

Media related to James V of Scotland at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to James V of Scotland at Wikimedia Commons

- James V of Scotland

- 1512 births

- 1542 deaths

- 16th-century monarchs in Europe

- 16th-century Scottish monarchs

- Burials at Holyrood Abbey

- Dukes of Rothesay

- House of Stuart

- Knights of the Garter

- Knights of the Golden Fleece

- Modern child rulers

- People from Linlithgow

- Scottish people of Welsh descent

- Scottish poets

- Scottish princes

- High Stewards of Scotland

- 16th-century Scottish peers

- People of Stirling Castle