Janamsakhis

| Part of a series on |

| Sikhism |

|---|

|

|

The Janamsakhis (Punjabi: ਜਨਮਸਾਖੀ, IAST: Janam-sākhī, lit. birth stories), are legendary biographies of Guru Nanak – the founder of Sikhism.[1] Popular in the Sikh history, these texts are considered by scholars as imaginary hagiographies of his life story, full of miracles and travels, built on a Sikh oral tradition and some historical facts.[1][2] The first Janamsakhis were composed between 50 and 80 years after his death.[1] Many more were written in the 17th and 18th century. The largest Guru Nanak Prakash, with about 9,700 verses, was written in the early 19th century.[2][3]

The four Janamsakhis that have survived into the modern era include the Bala, Miharban, Adi and Puratan versions, and each hagiography contradicts the other.[4][2] Each of these are in three parts, each with an idealized and adulatory description of Guru Nanak. The first part covers his childhood and early adulthood.[2] The second part describes him as a traveling missionary over thousands of miles and mythical places such as Mount Meru. The last part presents him as settled in Kartarpur with his followers.[2] These mythological texts are ahistorical and do not offer chronological, geographical or objective accuracy about Guru Nanak's life.[4] The Sikh writers were competing with mythological stories (mu'jizat) about Muhammad created by Sufi Muslims in medieval Punjab region of South Asia.[4][5]

The early editions of the Janam-sakhi manuscripts are more than Guru Nanak's life story. They relate each story with a teaching in the hymn of the Sikh scripture and illustrate a fundamental moral or teaching.[2] They thus invent the context and an exegetical foundation for some of the hymns of the Adi Granth.[2] They may have been an early attempt to reach people and popularize Sikhism across different age groups with a combination of abstract teachings and exciting fables for a personal connection between the Guru and the followers.[2] The various editions of Janamsakhi include stories such as fortune tellers and astrologers predicting at his birth of his destined greatness, he meeting mythical and revered characters from Hindu mythology, his touch creating a never drying fount of spring water, cobra snake offering shade to Guru Nanak while he was sleeping, Guru Nanak visiting and performing miracles at Mecca - a holy place for Muslims, and his visit to Mount Meru - a mythical place for Hindus, Buddhists and Jains.[4] At Mecca, the Janamsakhis claim Guru Nanak slept with his feet towards the Kaba which Muslims objected to but when they tried to rotate his feet away the Kaaba, all of Kaba and earth moved to remain in the direction of Guru Nanak's feet. The texts also claim Guru Nanak's body vanished after his death and left behind fragrant flowers, which Hindus and Muslims then divided, one to cremate and other to bury.[4][5]

Over 40 significant manuscript editions of the Janamsakhis are known, all composed between the 17th and early-19th centuries, with most of these in the Bala and Puratan sub-genre.[3] The expanded version containing the hagiographies of all ten Sikh Gurus is the popular Suraj Prakash by Santokh Singh. This poetic Janamsakhi is recited on festive occasions in Sikh Gurdwaras, Sikh ceremonies and festivals.[6][7]

Overview[]

All the Janamsakhis present a mythical idealized account of the life of Guru Nanak and his early companions. They feature miracles, episodes where mythical characters, fish or animal talk, and of supernatural conversations.[8] The Janamsakhis exist in many versions. Many of them contradict each other on material points and some have obviously been touched up to advance the claims of one or the other branches of the Guru's family, or to exaggerate the roles of certain disciples. Macauliffe compares the manipulation of Janam sakhis to the way Gnostic gospels were manipulated in the times of the early Church.[citation needed]

Sikh tradition[]

The Janamsakhis have been historically popular in the Sikh community and broadly believed as true, historical biography of the founder of their religion.[9] They have been recited at religious gatherings, shared as reverential fables with the young generation, and embedded in the cultural folklore over the centuries. Any academic questioning of their authenticity and critical comparative historical studies have "angered many Sikhs", states Toby Johnson – a scholar of Sikhism.[9] Guru Nanak is deeply revered by the devout Sikhs, the stories in the Janamsakhis are a part of their understanding of his divine nature and the many wonders he is believed to have performed.[10]

Critical scholarship[]

According to The Encyclopaedia Britannica, the Janam-sakhis are "imagined product of the legendary" stories of Guru Nanak's life, and "only a tiny fraction of the material found in them can be affirmed as factual".[1]

Max Arthur Macauliffe – a British civil servant, published his six volume translation of Sikh scripture and religious history in 1909.[11] This set has been an early influential source of Sikh Gurus and their history for writers outside of India. Macauliffe, and popular writers such as Khushwant Singh who cite him, presented the Janamsakhi stories as factual, though Macauliffe also expressed his doubts on their historicity.[11][12][13] Khushwant Singh similarly expresses his doubts, but extensively relied on the Janamsakhis in his A History of the Sikhs.[14] Macauliffe interspersed his translation of the Sikh scripture between Janamsakhis-derived mythical history of the Sikh Gurus.[15][11] Post-colonial scholarship has questioned Macauliffe's reliance on Janamsakhis as "uncritical" and "dubious", though one that pleased the Sikh community.[11]

The post-colonial era major studies led by W.H. McLeod – a scholar of Sikh literature and history, have examined the Janamsakhis by methods of scientific research and literary cross examination. These have examined over 100 episodes about Guru Nanak in the different Janamsakhis. According to McLeod and other scholars, there are some historical elements in these stories but one so small that they can be summarized in less than one typeset page. Rest is fiction and ahistorical.[9][16] McLeod's textual criticism, his empirical examination of genealogical and geographical evidence, examination of the consistency between the Sikh texts and their versions, philological analysis of historic Sikh literature, search for corroborating evidence in external sources and other critical studies have been influential among the Western academics and Indian scholars working outside India, but highly controversial within the Sikh community and some Sikh scholars based in Punjab.[16][17]

According to Singha and Kapura, the Janam sakhi authors incorporated miracles and supernatural elements because they were competing with and under the influence of similar miracle-filled Islamic literature in the Punjab region.[18] According to an alternate apologetic hypothesis, some Janamsakhis such as one written by Paida Mokha are accurate and true life stories of Guru Nanak and his travels to distant lands. The corruption such as Guru Nanak forecasting the birth of future Sikh leaders was deliberately added when "heretic" Sikh sects were formed by brothers or family relatives of the Sikh Gurus.[17]

Didactic texts[]

According to Toby Johnson, the Sikh Janamsakhis may have been the early didactic texts in the Sikh tradition.[19] The fantasy-filled stories are more than mere adulation of the founder of Sikhism. They generally include a teaching, a moral instruction along with an associated hymn found in the Sikh scripture. This, states Johnson, makes them a pedagogical texts.[19] They are, in this way, similar to pedagogical Puranas-style literature found in Buddhism, Hinduism and Jainism. They create and provide the context through a fable for recitation and an associated moral teaching to the reader or listener at a community gathering.[19] The episodes connect the fantastical with a concrete teaching that a devotee finds easier to understand, relate and connect. This naturally endears these fables to the devout disciples.[19]

Main Janamsakhis[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

Bhai Bala Janamsakhi[]

This is probably the most popular and well known Janamsakhi, in that most Sikhs and their Janamsakhi knowledge comes from this document. This work claims to be a contemporary account written by one Bala Sandhu in the Vikram Samvat year 1592 at the instance of the second Guru, Guru Angad. According to the author, he was a close companion of Guru Nanak and accompanied him on many of his travels. There are good reasons to doubt this contention:

- Guru Angad, who is said to have commissioned the work and was also a close companion of the Guru in his later years, was, according to Bala's own admission, ignorant of the existence of Bala.

- Bhai Gurdas, who has listed all Guru Nanak's prominent disciples whose names were handed down, does not mention the name of . (This may be an oversight, for he does not mention Rai Bular either.)

- Bhai Mani Singh's , which contains essentially the same list as that by Bhai Gurdas, but with more detail, also does not mention Bala Sandhu.

- It is only in the heretic janamsakhis of the Minas that we find first mention of Bhai Bala.

- The language used in this janamsakhi was not spoken at the time of Guru Nanak or Guru Angad, but was developed at least a hundred years later.

- Some of the hymns ascribed to Nanak are not his but those of the second and fifth Gurus.

- At several places expressions which gained currency only during the lifetime of the last Guru, Guru Gobind Singh (1666–1708), are used e.g. Waheguru ji ki Fateh. Bala's janamsakhi is certainly not a contemporary account; at best it was written in the early part of the 18th Century.

This janamsakhi has had an immense influence over determining what is generally accepted as the authoritative account of Guru Nanak Dev Ji's life. Throughout the nineteenth century the authority of the Bala version was unchallenged. An important work based on the Bhai Bala janam-sakhi is Santokh Singh's Gur Nanak Purkash commonly known as Nanak Parkash. Its lengthy sequel, Suraj Parkash carries the account up to the tenth Guru and contains a higher proportion of historical fact, this was completed in 1844.

In the first journey or udasi Guru Nanak Dev Ji left Sultanpur towards eastern India and included, in the following sequence : Panipat (Sheikh Sharaf), Delhi (Sultan Ibrahim Lodi), Hardwar, Allahbad, Banaras, Nanakmata, Kauru, Kamrup in Assam (Nur Shah), Talvandi (twelve years after leaving Sultanpur), Pak Pattan (Sheikh Ibrahim), Goindval, Lahore and Kartarpur.

The Second udasi was to the south of India with companion Bhai Mardana. Delhi, Ayodhya, Jagannath Puri, Rameswaram, Sri Lanka, Vindhya mountains, Narabad River, Ujjain, Saurashtra and Mathura

The third udasi was to the north : Kashmir, Mount Sumeru and Achal

The fourth udasi was to the west. Afghanistan, Persia, and Baghdad

Bhai Mani Singh’s Janamsakhi[]

The fourth and evidently the latest is the Gyan-ratanavali attributed to Bhai Mani Singh who wrote it with the express intention of correcting heretical accounts of Guru Nanak. Bhai Mani Singh was a Sikh of Guru Gobind Singh. He was approached by some Sikhs with a request that he should prepare an authentic account of Guru Nanak's life. This they assured him was essential as the Minas were circulating objectionable things in their version. Bhai Mani Singh referred them to the Var of Bhai Gurdas, but this, they maintained was too brief and a longer more fuller account was needed. Bhai Mani Singh writes :

Just as swimmers fix reeds in the river so that those who do not know the way may also cross, so I shall take Bhai Gurdas’s var as my basis and in accordance with it, and with the accounts that I have heard at the court of the tenth Master, I shall relate to you whatever commentary issues from my humble mind. At the end of the Janam-sakhi there is an epilogue in which it is stated that the completed work was taken to Guru Gobind Singh Ji for his seal of approval. Guru Sahib Ji duly signed it and commended it as a means of acquiring knowledge of Sikh belief.

The Miharban Janam-sakhi[]

Of all the manuscripts this is probably the most neglected as it has acquired a disagreeable reputation. Sodhi Miharban who gives his name to the janam-sakhi was closely associated with the Mina sect and the Minas were very hostile towards the Gurus around the period of Guru Arjan Dev Ji. The Minas were the followers of Prithi Chand the eldest son of Guru Ram Das Ji. Prithi Chand's behaviour was evidently unsatisfactory as he was passed over in favour of his younger brother, (Guru) Arjan Dev, when his father chose a successor. The Minas were a robber tribe and in Punjabi the word has come to mean someone who conceals his true evil intent. The Minas were subsequently execrated by Guru Gobind Singh Ji and Sikhs were instructed to have no dealings with them. The sect is now extinct. It is said that it was due to this janam-sakhi and its hostility towards the Gurus that prompted Bhai Gurdas Ji's account and the commission of the Gyan-ratanavali.

The first three sakhis recount the greatness of Raja Janak and describes an interview with God wherein Raja Janak is instructed that he is to return to the world once again to propagate His Name. Details of Guru Nanak's birth are given in the fourth sakhi and his father was Kalu, a Bedi and his mother Mata Tripta. The account of Guru Ji learning to read from the pundit is also recounted here. After the interlude at Sultanpur Guru Nanak Dev Ji set out to Mount Sumeru. Climbing the mountain Guru Ji found all nine Siddhas seated there – Gorakhnath, Mechhendranath, Isarnath, Charapatnath, Barangnath, Ghoracholi, Balgundai, Bharathari and Gopichand. Gorakhnath asked the identity of the visitor and his disciple replied, "This is Nanak Bedi, a pir and a bhagat who is a householder." What follows is a lengthy discourse with the siddhas which ends with the siddhas asking what is happening in the evil age of Kali Yuga. Guru Ji responds with three slogans :

- There is a famine of truth, falsehood prevails, and in the darkness of kaliyug men have become ghouls

- The kaliyug is a knife, kings are butchers, dharama has taken wings and flown

- Men give as charity the money they have acquired by sinful means

Editions[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

Many other janamsakhis have since been discovered. They follow the above two in all material points.

The term Puratan janamsakhis means ancient janam-sakhis and is generally used with reference to the composite work which was compiled by Bhai Vir Singh and first published in 1926. Of the still existing copies of the Puratan Janam-sakhis the two most important were the Colebrooke and Hafizabad versions. The first of these was discovered in 1872, the manuscript had been donated to the library of the east India company by H.T. Colebrooke and is accordingly known as the Colebrooke or Vailaitwali Janamsakhi. Although there is no date on it the manuscript points to around 1635.

In the year 1883 a copy of a janamasakhi was dispatched by the India Office Library in London for the use of Dr. Trumpp and the Sikh scholars assisting him. (It had been given to the library by an Englishman called Colebrook; it came to be known as the Vilayat Vali or the foreign janamsakhi.) This janamsakhi was the basis of the accounts written by Trumpp, Macauliffe, and most Sikh scholars. Gurmukh Singh of the Oriental College, Lahore, found another janamsakhi at Hafizabad which was very similar to that found by Colebrook. Gurmukh Singh who was collaborating with Mr. Macauliffe in his research on Sikh religion, made it available to the Englishman, who had it published in November 1885.

According to the Puratan Janamsakhi, Guru Nanak Dev Ji was born in the month of Vaisakh, 1469. The date is given as the third day of the light half of the month and the birth is said to have taken place during the last watch before dawn. His father Kalu was a khatri of the Bedi sub-cast and lived in a village Rai Bhoi di Talwandi; his mother's name is not given. When Guru Ji turned seven he was taken to a pundit to learn how to read. After only one day he gave up reading and when the pundit asked him why Guru Ji lapsed into silence and instructed him at length on the vanity of worldly learning and the contrasting value of the Divine Name of God. The child began to show disturbing signs of withdrawal from the world. He was sent to learn Persian at the age of nine but returned home and continued to sit in silence. Locals advised his father that Nanak should be married. This advice was taken and at the age of twelve a betrothal was arranged at the house of Mula of the Chona sub-caste. Sometime later Nanak moved to Sultanpur where his sister Nanaki was married. Here he took up employment with Daulat Khan. One day Nanak went to the river and while bathing messengers of God came and he was transported to the divine court. There he was given a cup of nectar (amrita) and with it came the command “ Nanak, this is the cup of My Name (Naam). Drink it.” This he did and was charged to go into the world and preach the divine Name.

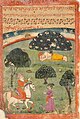

Gallery[]

Images from the third oldest Guru Nanak Janam Sakhi manuscript known (Bhai Sangu Mal MS, published in August 1733 CE, preserved at the British Library):[20]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Guru Nanak, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Brian Duignan (2017)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Toby Braden Johnson (2014). Pashaura Singh and Louis E. Fenech (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 182–185. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Knut A. Jacobsen; Gurinder Singh Mann; Kristina Myrvold; Eleanor M. Nesbitt, eds. (2017). Brill's Encyclopedia of Sikhism. Brill Academic. pp. 173–181. ISBN 978-90-04-29745-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (2011), Sikhism: An Introduction, IB Tauris, ISBN 978-1848853218, pages 1-8

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (1992), The Myth of the Founder: The Janamsākhīs and Sikh Tradition, History of Religions, Vol. 31, No. 4, Sikh Studies, pages 329-343

- ^ Pashaura Singh (2006). Life and Work of Guru Arjan: History, Memory, and Biography in the Sikh Tradition. Oxford University Press. pp. 54–56. ISBN 978-0-19-908780-8.

- ^ Christopher Shackle (2014). Pashaura Singh and Louis Fenech (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-19-100411-7.

- ^ Kristin Johnston Largen (2017). Finding God Among our Neighbors, Volume 2: An Interfaith Systematic Theology. Fortress Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1-5064-2330-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Toby Braden Johnson (2012). Pashaura Singh and Michael Hawley (ed.). Re-imagining South Asian Religions: Essays in Honour of Professors Harold G. Coward and Ronald W. Neufeldt. BRILL Academic. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-90-04-24236-4., Quote="What was traditionally held to be the true biography of the Guru (...)"

- ^ W.H. McLeod (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism. University of Chicago Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-226-56085-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d JS Grewal (1993). John Stratton Hawley; Gurinder Singh Mann (eds.). Studying the Sikhs: Issues for North America. SUNY Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0-7914-1425-5.

- ^ Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. A&C Black. pp. 85–89. ISBN 978-1-4411-0231-7.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth W. (1973). "Ham Hindū Nahīn: Arya Sikh Relations, 1877–1905". The Journal of Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 32 (3): 457–475. doi:10.2307/2052684. JSTOR 2052684.

- ^ Khushwant Singh (1963). A History of the Sikhs. Princeton University Press. pp. 31–48 with the extensive citing of Janamsakhis in the footnotes, 299–301, other chapters.

- ^ Donald Dawe (2011), Macauliffe, Max Arthur, Encyclopedia of Sikhism, Volume III, Harbans Singh (Editor), Punjabi University, Patiala;

The translation of Guru Nanak's Janamsakhi and his hymns in the Guru Granth Sahib are in Macauliffe's Volume I, The Sikh Religion (1909) - ^ Jump up to: a b Tony Ballantyne (2006). Between Colonialism and Diaspora: Sikh Cultural Formations in an Imperial World. Duke University Press. pp. 7–12. ISBN 0-8223-3824-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Trilochan Singh (1994). Ernest Trumpp and W.H. McLeod as scholars of Sikh history religion and culture. International Centre of Sikh Studies. pp. 272–275.

- ^ Kirapāla Siṅgha; Prithīpāla Siṅgha Kapūra (2004). Janamsakhi tradition: an analytical study. Singh Brothers. pp. 26–28. ISBN 9788172053116.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Toby Braden Johnson (2012). Pashaura Singh and Michael Hawley (ed.). Re-imagining South Asian Religions: Essays in Honour of Professors Harold G. Coward and Ronald W. Neufeldt. BRILL Academic. pp. 90–98. ISBN 978-90-04-24236-4.

- ^ Janam-sākhī, British Library MS Panj B 40

- Macauliffe, M.A (1909). The Sikh Religion: Its Gurus Sacred Writings and Authors. Low Price Publications. ISBN 81-7536-132-8.

- Singh, Khushwant (1963). A History of the Sikhs: 1469-1839 Vol.1 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-567308-5.

External links[]

- Sri Guru Babey ji di Chahun Jugi Janam Sakhi - An Autobiography of Eternal-Nanak - New Light on Eternally-old ATMAN

- Janam Sakhi or The Biography of Guru Nanak, Founder of The Sikh Religion

- Janamsakhian Daa Vikas tey Itihasik Vishesta - Dr. Kirpal Singh Tract No. 434

- Janamsakhi manuscript

- Gyan Ratnavali

- Sikh literature

- Guru Nanak Dev