Jesus Christ Superstar (film)

| Jesus Christ Superstar | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Norman Jewison |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Jesus Christ Superstar by Tim Rice, Andrew Lloyd Webber |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Douglas Slocombe |

| Edited by | Antony Gibbs |

| Music by | Andrew Lloyd Webber |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 106 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.5 million (estimated)[3] |

| Box office | $24.5 million[4] |

Jesus Christ Superstar is a 1973 American musical drama film directed by Norman Jewison and jointly written for the screen by Jewison and Melvyn Bragg; they based their screenplay on the 1970 rock opera of the same name, the libretto (book and lyrics) of which were written by Tim Rice and whose music was composed by Andrew Lloyd Webber. The film, featuring a cast of Ted Neeley, Carl Anderson, Yvonne Elliman, Barry Dennen, Bob Bingham, and Kurt Yaghjian, centers on the conflict between Judas and Jesus[5] during the week of the crucifixion of Jesus.

Neeley, Anderson, and Elliman were nominated for Golden Globe Awards in 1974 for their portrayals of Jesus, Judas, and Mary Magdalene, respectively. It attracted criticism from some religious groups and received mixed reviews from critics.[6]

Plot[]

The film's cast and crew are seen traveling by bus to the Israeli desert, in order to re-enact the Passion of Christ. They assemble their props and get into costume. One of the group, Ted Neeley, is surrounded by the others. He puts on a white robe and emerges as Jesus ("Overture").

The story begins with Judas, who is worried about Jesus' popularity; He is being hailed as the Son of God, but Judas feels He has too much faith in His own message. Judas fears the consequences of their growing movement ("Heaven on Their Minds"). The other disciples vainly badger Jesus for information about His future plans ("What's the Buzz?"). Judas arrives and subsequently declares that Jesus should not associate with the likes of Mary Magdalene (historically accused of being a prostitute). Angrily, Jesus tells Judas that he should leave Mary alone because his own slate is not clean. Jesus then accuses all the Apostles of not caring about Him ("Strange Thing Mystifying"). That night at the Temple, Caiaphas is worried that the people will crown Jesus as king, which the Romans will take for an uprising. Annas tries to allay his fears, but he finally sees Caiaphas's point. Annas suggests that they convene the council and explain Caiaphas's fears to them. Caiaphas agrees ("Then We Are Decided"). As Jesus and the Apostles settle for the night, Mary soothes him with some expensive ointment. Judas says that such money should be given to the poor, rather than squandered like this. Jesus rebukes him again, explaining that the poor will be around always, but He Himself will not ("Everything's Alright").

The next day at the Temple of Jerusalem, the Pharisees and priests discuss their fears about Jesus. Caiaphas tells them that there is only one solution: like John the Baptist, Jesus must be executed for the sake of the nation ("This Jesus Must Die"). As Jesus and His followers joyfully arrive in Jerusalem, Caiaphas orders Him to disband the crowd for fear of a riot. Jesus responds that such a gesture would be futile, and proceeds to greet the masses instead ("Hosanna"). Later, Simon and a horde of fellow Zealots voice their admiration for Jesus ("Simon Zealotes"). Though Jesus initially appreciates this, He becomes worried when Simon suggests directing the crowd towards an uprising against their Roman occupiers. Jesus sadly dismisses this suggestion, saying that they do not understand His true purpose ("Poor Jerusalem").

Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea, reveals that he has dreamed about a Galilean man (Jesus) whom he will be pressured to execute and that he will be blamed for this man's death ("Pilate's Dream"). Jesus and His followers arrive at the temple, which has been taken over by money changers and prostitutes ("The Temple"). The enraged priests watch from the background as, to Judas's horror, a furious Jesus destroys the stalls and forces the vendors to leave ("My Temple Should Be..."). Wandering alone outside the city, Jesus is surrounded by lepers seeking His help. Jesus heals as many of them as possible, but is overwhelmed by their sheer numbers; He eventually gives up, screaming at them to leave Him alone. That night, Mary comforts Jesus as He goes to sleep ("Everything's Alright [Reprise]"). Mary loves Jesus, but is confused because He is so unlike any other man she has met ("I Don't Know How to Love Him"). Judas goes to the priests and expresses his concerns, along with his worries about the consequences of betraying Jesus ("Damned for All Time"). Taking advantage of Judas's doubts, the priests offer him money for leading them to Jesus. Judas initially refuses, but Caiaphas and Annas win him over by pointing out that he could use the money to help the poor. Judas reveals that Jesus will be at the Garden of Gethsemane on Thursday night ("Blood Money").

At the Last Supper in the garden, Jesus reveals that he knows Peter will deny Him and that Judas will betray Him. A bitter argument between Jesus and Judas ensues, as Judas berates Jesus for (supposedly) destroying the very hopes and ideals which He Himself gave them. Judas threatens to ruin Jesus' ambition by staying. Jesus tells him to depart, which he finally does after rhetorically asking why Jesus let the things he did get out of hand ("The Last Supper"). As the Apostles fall asleep, an upset Jesus goes deeper into Gethsemane to pray about His imminent death; reluctantly, He agrees to go forward with God's plan ("Gethsemane [I Only Want to Say]"). Jesus waits for Judas, who arrives accompanied by guards. He betrays Jesus with a kiss. The disciples offer to fight the guards but stand down at Jesus' urging. Jesus is taken to Caiaphas' house, found guilty of blasphemy, and sent to Pilate ("The Arrest"). Peter, meanwhile, is accused of being one of Jesus's followers; fearfully, he denies Jesus three times ("Peter's Denial"). Jesus is taken to Pilate's residence; the governor mocks Him, unaware that Jesus is the man from his dream. Since he does not deal with Jews, Pilate sends Jesus to King Herod ("Pilate and Christ"). The flamboyant Herod is excited to finally meet Jesus, for this is a chance to confirm the hype that has been going around. Herod urges Jesus to perform various miracles; when He doesn't, Herod dismisses Him as "nothing but a fraud." He has the guards return Jesus to Pilate ("King Herod's Song [Try It And See]").

Mary and the Apostles remember how things began, and wish that their situation had not gotten so out of hand ("Could We Start Again Please?"). Jesus is flung into a cell; there He is seen by Judas, who now regrets his part in the arrest. Judas hurls his money to the ground and curses at the priests, before running into the desert. Overcome by grief and regret for betraying Jesus, Judas blames God for his woes by giving him the role of the betrayer. While Judas hangs himself ("Judas' Death"), Jesus is taken back to Pilate who proceeds to question Him; Herod is also present but doesn't bother to testify, in view of his contempt for Jesus. Caiaphas testifies on Herod's behalf. Although he thinks Jesus is deluded, Pilate realizes that He has committed no actual crime. He has Jesus scourged; Herod is gleeful at first, but subsequently revolted, and eventually terror-stricken. Pilate's bemused indifference turns to a frenzy of confusion and anger, mostly at the crowd's irrational bloodthirst, but also at Jesus' inexplicable resignation and refusal to defend Himself. Pilate realizes he has no option but to have Jesus executed, or the masses will grow violent ("Trial Before Pilate [Including The Thirty-Nine Lashes]"). An enraged Pilate decrees the death sentence as demanded by the priests. Pilate then makes a great show of washing his hands of Jesus' fate. Jesus's appearance transforms, the heavens open, and a white-jumpsuit-clad Judas descends on a silver cross. Judas laments that Jesus should have returned as the Messiah today, in the 1970s; He would have been more popular, and His message easier to spread. Judas also wonders what Jesus thinks of other religions' prophets...and, ultimately, if Jesus thinks He's who they say He is, possibly meaning the Son of God ("Superstar"). Judas' questions go unanswered. Jesus is sent to die ("The Crucifixion") amid ominous, atonal music; He says some of His final words before dying.

As the film ends all of the performers, now out of costume, board their bus. Only Barry Dennen, Yvonne Elliman, and Carl Anderson—who had played (respectively) Pilate, Mary Magdalene, and Judas—notice that fellow performer Ted Neeley, who had played Jesus, seems to be missing. The bus departs as a shepherd and his flock cross the hillside beneath the now-empty cross ("John Nineteen Forty-One").

Cast[]

- Ted Neeley as Jesus Christ

- Carl Anderson as Judas Iscariot

- Yvonne Elliman as Mary Magdalene

- Barry Dennen as Pontius Pilate

- Bob Bingham as Caiaphas

- Larry Marshall as Simon Zealotes

- Josh Mostel as King Herod

- Kurt Yaghjian as Annas

- Philip Toubus as Peter

Musical numbers[]

- "Overture"

- "Heaven on Their Minds"

- "What's the Buzz?"

- "Strange Thing Mystifying"

- "Then We Are Decided"

- "Everything's Alright"

- "This Jesus Must Die"

- "Hosanna"

- "Simon Zealotes"

- "Poor Jerusalem"

- "Pilate's Dream"

- "The Temple"

- "Everything's Alright (Reprise)"

- "I Don't Know How to Love Him"

- "Damned for All Time"

- "Blood Money"

- "The Last Supper"

- "Gethsemane (I Only Want to Say)"

- "The Arrest"

- "Peter's Denial"

- "Pilate and Christ"

- "Hosanna (Reprise)"

- "King Herod's Song"

- "Could We Start Again Please?"

- "Judas' Death"

- "Trial Before Pilate (Including the 39 Lashes)"

- "Superstar"

- "The Crucifixion"

- "John 19:41"

Production[]

Development[]

During filming of Fiddler on the Roof, Barry Dennen, who played Pilate on the original-cast concept album, suggested to Norman Jewison that he should direct Jesus Christ Superstar as a film. After hearing the album, Jewison agreed.

Casting[]

The cast consisted mostly of actors from the Broadway show, with Ted Neeley and Carl Anderson starring as Jesus and Judas respectively. Neeley had played a reporter and a leper in the Broadway version, and understudied the role of Jesus. Likewise, Anderson understudied Judas, but took over the role on Broadway and Los Angeles when Ben Vereen fell ill. Along with Dennen, Yvonne Elliman (Mary Magdalene), and Bob Bingham (Caiaphas) reprised their Broadway roles in the film (Elliman, like Dennen, had also appeared on the original concept album). Originally, Jewison wanted Ian Gillan, who played Jesus on the concept album, to reprise the role for the film, but Gillan turned down the offer, deciding that he would please fans more by touring with Deep Purple. The producers also considered Micky Dolenz (from The Monkees) and David Cassidy to play Jesus before deciding to go with Neeley.[8] "With the exception of Barry Dennen who played Pontius Pilate and Josh Mostel who played King Herod — for everybody else, it was their first time on camera and first major motion picture. It was a learning process throughout."[9]

Filming[]

The film was shot in Israel (primarily at the ruins of Avdat, Beit Guvrin National Park, and Beit She'an) and other Middle Eastern locations in 1972.[10] in May of 2021 several Israel tour guide classes recognized the tree that was in the original movie.[1]

Companies[]

As producer Robert Stigwood was not yet known to have formed "The Robert Stigwood Organization," Jesus Christ Superstar is not generally considered a production of RSO Films, the movies-and-television arm of that organization. Nor, in spite of Andrew Lloyd Webber having composed the musical score, is the film commonly identified with "The Really Useful Company," through which Lloyd Webber was doing most of his stage and screen work as of late November 2020. The film is considered a Universal Picture, since Universal did fund and distribute it.

Alterations[]

Like the stage show, the film gave rise to controversy even with changes made to the script. Some of the lyrics were changed for the film. The reprise of "Everything's Alright", sung before the song "I Don't Know How to Love Him" by Mary to Jesus, was abridged, leaving only the closing lyric "Close your eyes, close your eyes and relax, think of nothing tonight" intact, while the previous lyrics were omitted, including Jesus's "And I think I shall sleep well tonight.". In a scene where a group of beggars and lepers overwhelms Jesus, "Heal yourselves!" was changed to "Leave me alone!", and in "Judas' Death", Caiaphas' line "What you have done will be the saving of Israel" was changed to "What you have done will be the saving of everyone."

The lyrics of "Trial Before Pilate" contain some notable alterations and additions. Jesus's line "There may be a kingdom for me somewhere, if I only knew" is changed to "if you only knew." The film version also gives Pilate more lines (first used in the original Broadway production) in which he addresses the mob with contempt when they invoke the name of Caesar: "What is this new/Respect for Caesar?/Till now this has been noticeably lacking!/Who is this Jesus? Why is he different?/You Jews produce messiahs by the sackful!" and "Behold a man/Behold your shattered king/You hypocrites!/You hate us more than him!" These lines for Pilate have since been in every production of the show.

The soundtrack contains two songs that are not on the original concept album. "Then We Are Decided", in which the troubles and fears of Annas and Caiaphas regarding Jesus are better developed, is original to the film. The soundtrack also retains the song "Could We Start Again Please?" which had been added to the Broadway show and to stage productions. Most of the other changes have not been espoused by later productions and recordings, although most productions tend to retain the expanded version of "Trial Before Pilate".

Reception[]

Box office[]

Jesus Christ Superstar grossed $24.5 million at the box office[4] and earned North American rentals of $10.8 million in 1973,[11] against an estimated production budget of $3.5 million.[3] It was the highest-grossing musical in the United States and Canada for the year.[12]

Critical response[]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 52% based on 25 reviews, with an average rating of 5.93/10. The website's critics consensus reads: "Jesus Christ Superstar has too much spunk to fall into sacrilege, but miscasting and tonal monotony halts this musical's groove."[13] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 64 out of 100 based on 7 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[14]

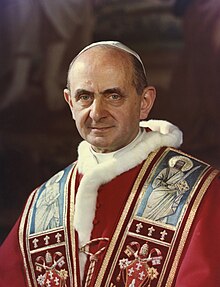

Jewison was able to show the film to Pope Paul VI. Ted Neeley later remembered that the pope "openly loved what he saw. He said, 'Mr. Jewison, not only do I appreciate your beautiful rock opera film, I believe it will bring more people around the world to Christianity, than anything ever has before.'"[15][3] For the Pope, Mary Magdalene's song "I Don't Know How to Love Him" "had an inspired beauty".[16] Nevertheless, the film as well as the musical were criticized by some religious groups.[6] As a New York Times article reported, "When the stage production opened in October 1971, it was criticized not only by some Jews as anti-Semitic, but also by some Catholics and Protestants as blasphemous in its portrayal of Jesus as a young man who might even be interested in sex."[17] A few days before the film version's release, the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council described it as an "insidious work" that was "worse than the stage play" in dramatizing "the old falsehood of the Jews' collective responsibility for the death of Jesus," and said it would revive "religious sources of anti-Semitism."[18] Jewison argued in response that the film "never was meant to be, or claimed to be an authentic or deep theological work."[19]

Roger Ebert gave the film three stars out of four and wrote, "a bright and sometimes breathtaking retelling of the rock opera of the same name. It is, indeed, a triumph over that work; using most of the same words and music, it succeeds in being light instead of turgid, outward-looking instead of narcissistic. Jewison, a director of large talent, has taken a piece of commercial shlock and turned it into a Biblical movie with dignity."[20] Conversely, Howard Thompson of The New York Times wrote, "Broadway and Israel meet head on and disastrously in the movie version of the rock opera 'Jesus Christ Superstar,' produced in the Biblical locale. The mod-pop glitter, the musical frenzy and the neon tubing of this super-hot stage bonanza encasing the Greatest Story are now painfully magnified, laid bare and ultimately patched beneath the blue, majestic Israeli sky, as if by a natural judgment."[21] Arthur D. Murphy of Variety wrote that the film "in a paradoxical way is both very good and very disappointing at the same time. The abstract film concept ... veers from elegantly simple through forced metaphor to outright synthetic in dramatic impact."[22][23] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film two-and-a-half stars out of four and called the music "more than fine," but found the character of Jesus "so confused, so shapeless, the film cannot succeed in any meaningful way." Siskel also agreed with the accusations of the film being anti-Semitic.[24] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "The faults are relative, the costs of an admirable seeking after excellence, and the many strong scenes, visually and dramatically, in 'Superstar' have remarkable impact: the chaos of the temple, the clawing lepers, the rubrics of the crucifixion itself."[25] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post panned the film as "a work of kitsch" that "does nothing for Christianity except to commercialize it."[26]

Tim Rice said Jesus was seen through Judas' eyes as a mere human being. Some Christians found this remark, as well as the fact that the musical did not show the resurrection, to be blasphemous. While the actual resurrection was not shown, the closing scene of the movie subtly alludes to the resurrection (though, according to Jewison's commentary on the DVD release, the scene was not planned this way).[27] Some found Judas too sympathetic; in the film, it states that he wants to give the thirty pieces of silver to the poor, which, although Biblical, leaves out his ulterior motives.[28] Biblical purists pointed out a small number of deviations from biblical text as additional concerns; for example, Pilate himself having the dream instead of his wife, and Catholics argue the line "for all you care, this bread could be my body" is too Protestant in theology, although Jesus does say in the next lines, "This is my blood you drink. This is my body you eat."

Accolades[]

The film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Adapted Score. It lost to The Sting. The film was nominated for the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture - Musical or Comedy. It lost to American Graffiti. Golden Globe nominations went to Ted Neely and Carl Anderson for Best Actor in a Comedy or Musical, and Yvonne Elliman for Best Actress in a Comedy or Musical. They lost to George Segal and Glenda Jackson in A Touch of Class.

Douglas Slocombe won the best cinematography award given by the British Society of Cinematographers, while Norman Jewison won the David di Donatello Award for best foreign film, as producer.[29]

In the 1980 book The Golden Turkey Awards by Michael Medved and Harry Medved, Neeley was given "an award" for "The Worst Performance by an Actor as Jesus Christ".[30] Neeley went on to recreate the role of Jesus in numerous national stage tours of the rock musical.

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "I Don't Know How to Love Him" – Nominated[31]

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[32]

Years later the film was still popular, winning a 2012 Huffington Post competition for "Best Jesus Movie."[33]

Soundtrack[]

The soundtrack for the film was released on vinyl by MCA Records in 1973.[34][35] It was re-released on CD in 1993[36] and reissued in 1998 for its 25th Anniversary.[37][38]

|

|

The soundtrack for the film was released in the U.S. on vinyl by MCA Records (MCA 2-11000) in 1973, as: JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR / The Original Motion Picture Sound Track Album.

Charts[]

| Chart (1974) | Position |

|---|---|

| Australia (Kent Music Report)[39] | 25 |

[]

2000 version[]

Another film version was made for video in 2000, directed by Gale Edwards and Nick Morris as part of the long-running Great Performances anthology.[40][41] It was shot entirely on indoor sets including graffiti on the wall. Webber, the composer, has stated in the making-of documentary that this was the version closest to what he had originally envisioned for the project. He chose Gale Edwards to direct after seeing her interpretation of the musical in Dublin, which featured a more modernistic and sinister approach than the original stage productions.

In the main roles, it starred Glenn Carter as Jesus, Jérôme Pradon as Judas, and Reneé Castle as Mary Magdalene.[42] Other cast members are Fred Johanson as Pontius Pilate, Michael Shaeffer as Annas, Frederick B. Owens as Caiaphas, Rik Mayall as Herod, Tony Vincent and as Simon Zealotes, Cavin Cornwall as Peter; Pete Gallagher, Michael McCarthy and Philip Cox as the first, second and third priests respectively and various others as part of the ensemble.[40][43]

Other versions[]

In a 2008 interview with Variety magazine, film producer Marc Platt stated that he was in discussions with several filmmakers for a remake of Jesus Christ Superstar.[44]

In 2013, a Blu-ray "40th Anniversary" edition of the film was released, featuring commentary from the director and Ted Neeley, an interview with Tim Rice, a photo gallery and a clip of the original trailer.[45]

In 2015, Neeley announced the upcoming release of a documentary entitled Superstars: The Making of and Reunion of the film 'Jesus Christ Superstar' about the production of the film.[46]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Stereotype 'Superstar'". The Washington Post. June 25, 1973. B5. "The film premieres Tuesday evening at Washington's Uptown theater and opens to the public Wednesday."

- ^ "JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR (A)". British Board of Film Classification. July 17, 1973. Retrieved May 15, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jesus Christ Superstar at the TCM Movie Database

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Jesus Christ Superstar (1973)". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Archived from the original on August 24, 2014. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ^ Jewison, Norman (2004). This Terrible Business Has Been Good to Me. An Autobiography. Toronto: Key Porter Books. p. 164. ISBN 1-55263211-3. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Forster, Arnold; Epstein, Benjamin (1974). The New Anti-Semitism. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 91–101.

- ^ Coates, Paul (2017) [2003]. Cinema, Religion and the Romantic Legacy. Taylor & Francis. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-35195153-1. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

It is thus surprisingly and unexpectedly powerful when his Gethsemane plea for the cup to pass from him issues in a rapid, proleptic montage of traditional Christian images of the Crucifixion, many of them drawn from one of the most fearsome of such paintings, the Isenheim Altar of Matthias Grünewald.

- ^ Campbell, Richard H.; Pitts, Michael R. (1981). The Bible On Film. A Checklist, 1897-1980. Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press. p. 169]. ISBN 0-81081473-0. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Martinfield, Sean (August 20, 2013). "A Conversation With Ted Neeley, Hollywood's 'Jesus Christ Superstar'". HuffPost. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ "Jesus Christ Superstar (1973). Filming & Production". IMDb. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1973", Variety, January 9, 1974, p. 19.

- ^ Frederick, Robert B. (January 8, 1975). "'Sting', 'Exorcist' In Special Class At B.O. in 1974". Variety. p. 24.

- ^ "Jesus Christ Superstar (1973)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on November 27, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- ^ "Jesus Christ Superstar Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on September 28, 2018. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ Heaton, Michael. "'Jesus Christ Superstar': Ted Neeley talks about the role that changed his career, life" Archived April 11, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 26, 2015, accessed April 11, 2021.

- ^ Pepper, Curtis Bill (April 10, 1977). "A Day in the Life of the Pope". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda (August 8, 1973). "SUPERSTAR' FILM RENEWS DISPUTES:Jewish Groups Say Opening Could Stir Anti-Semitism Reasons Given Company Issues Statement". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 12, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ Spiegel, Irving (June 24, 1973). "Jewish Unit Calls Movie 'Insidious'". The New York Times. 44.

- ^ Smith, Terence (July 14, 1973). "Israeli Government Moves to Dissociate Itself From 'Jesus Christ Superstar'". The New York Times. 19.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 15, 1973). "Jesus Christ Superstar". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (August 9, 1973). "Mod-Pop 'Superstar' Comes to Screen". Archived May 6, 2019, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times. 28.

- ^ Murphy, Arthur D. (June 27, 1973). "Film Reviews: Jesus Christ Superstar". Variety. 20.

- ^ Variety Staff (January 1, 1973). "Jesus Christ Superstar". Variety. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (July 24, 1973). "...Superstar". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 4.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (July 15, 1973). "Film 'Superstar' Joins Present, Past". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, p. 21.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (June 29, 1973). "Good Book, Bad Movie". The Washington Post. B11.

- ^ Spoilers section Archived April 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine on IMDb.

- ^ Hebron, Carol A. (2016). Judas Iscariot: Damned or Redeemed. A Critical Examination of the Portrayal of Judas in Jesus Films (1902-2014). London: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-5676-6830-1. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0070239/awards?ref_=tt_awd Archived May 1, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- ^ Harry Medved and Michael Medved, The golden turkey awards: nominees and winners, the worst achievements in Hollywood history, Putnam, 1980, p. 95.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs Nominees" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ^ "In The Category Of Best Jesus Movie The Winner Is." March 10, 2012. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ Jesus Christ Superstar [MCA Film Soundtrack] at AllMusic.

- ^ Jesus Christ Superstar (The Original Motion Picture Sound Track Album) at Discogs (list of releases).

- ^ Jesus Christ Superstar (The Original Motion Picture Sound Track Album). 1993 CD at Discogs.

- ^ Jesus Christ Superstar [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack 25th Anniversary Reissue] at AllMusic.

- ^ Jesus Christ Superstar (The Original Motion Picture Sound Track Album). Reissue, Remastered in 1998 at Discogs.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 281. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Great Performances: Jesus Christ Superstar". IMDb. Archived from the original on March 19, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ "Jesus Christ Superstar". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ Leonard, John (April 16, 2001). "The Joy of Sets". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved March 15, 2019.

- ^ "All actors in Jesus Christ Superstar (2000)". FilmVandaag (in Dutch). Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ Gans, Andrew (July 15, 2011). "Wicked Film and 'Jesus Christ Superstar' Remake on Platt's Plate". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ "Jesus Christ Superstar Blu-ray". Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ^ "Ted Neeley - official site of musician and actor from Jesus Christ Superstar - Home". Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jesus Christ Superstar (film). |

- 1973 films

- English-language films

- 1970s musical drama films

- 1973 drama films

- American films

- American musical drama films

- American rock musicals

- Caiaphas

- Cultural depictions of Judas Iscariot

- Cultural depictions of Pontius Pilate

- Cultural depictions of Saint Peter

- Films based on adaptations

- Films based on albums

- Films based on musicals

- Films about Christianity

- Films directed by Norman Jewison

- Films produced by Robert Stigwood

- Foreign films shot in Israel

- Jesus Christ Superstar

- Musicals by Andrew Lloyd Webber

- Portrayals of Mary Magdalene in film

- Portrayals of Jesus in film

- Religious controversies in film

- Sung-through musical films

- Universal Pictures films