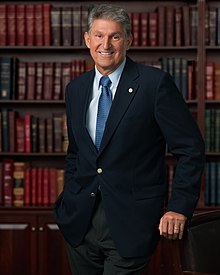

Joe Manchin

Joe Manchin | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from West Virginia | |

| Assumed office November 15, 2010 Serving with Shelley Moore Capito | |

| Preceded by | Carte Goodwin |

| Chair of the Senate Energy Committee | |

| Assumed office February 3, 2021 | |

| Preceded by | Lisa Murkowski |

| Ranking Member of the Senate Energy Committee | |

| In office January 3, 2019 – February 3, 2021 | |

| Preceded by | Maria Cantwell |

| Succeeded by | John Barrasso |

| Chair of the National Governors Association | |

| In office July 11, 2010 – November 15, 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Jim Douglas |

| Succeeded by | Christine Gregoire |

| 34th Governor of West Virginia | |

| In office January 17, 2005 – November 15, 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Bob Wise |

| Succeeded by | Earl Ray Tomblin |

| 27th Secretary of State of West Virginia | |

| In office January 15, 2001 – January 17, 2005 | |

| Governor | Bob Wise |

| Preceded by | Ken Hechler |

| Succeeded by | Betty Ireland |

| Member of the West Virginia Senate | |

| In office December 1, 1986 – December 1, 1996 | |

| Preceded by | Anthony Yanero |

| Succeeded by | Roman Prezioso |

| Constituency |

|

| Member of the West Virginia House of Delegates from the 31st district | |

| In office December 1, 1982 – December 1, 1986 | |

| Preceded by | Clyde See |

| Succeeded by | Duane Southern |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Joseph Manchin III August 24, 1947 Farmington, West Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 3, including Heather Bresch |

| Education | West Virginia University (BBA) |

| Signature | |

| Website | Senate website |

Joseph Manchin III[1] (born August 24, 1947) is an American politician serving as the senior United States senator from West Virginia, a seat he has held since 2010. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the 34th governor of West Virginia from 2005 to 2010 and the 27th secretary of state of West Virginia from 2001 to 2005.

Manchin has called himself a "moderate conservative Democrat" and is often cited as the most conservative Democrat in the Senate.[2][3] West Virginia has become one of the most heavily Republican states in the country,[4] but Manchin has continued to see electoral success. He won the 2004 gubernatorial election by a large margin and was reelected by an even larger margin in 2008; in both years, Republican presidential candidates won West Virginia. Manchin won the 2010 special election to fill the Senate seat vacated by incumbent Democrat Robert Byrd's death with 54% of the vote. He was elected to a full term in 2012 with 61% of the vote and reelected in 2018 with just under 50% of the vote, as the state had become increasingly partisan. He became the state's senior U.S. Senator when Jay Rockefeller retired in 2015.

As a member of Congress, Manchin is known for his support of bipartisanship, voting or working with Republicans on issues such as abortion and gun ownership. He opposed the energy policies of President Barack Obama, voted against cloture for the Don't Ask, Don't Tell Repeal Act of 2010 (he did not vote on the bill itself), voted to remove federal funding for Planned Parenthood in 2015, supported President Donald Trump's immigration policies and voted to confirm most of his cabinet and judicial appointees, including Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh. But Manchin has also repeatedly voted against attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare), voted to preserve funding for Planned Parenthood in 2017, and voted against the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. In addition, he voted to convict President Trump in both of his impeachment trials. Manchin is a prominent opponent of policy proposals from the progressive wing of his party, including Medicare For All, abolishing the filibuster, increasing the number of justices on the Supreme Court, increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, and attempts to defund the police.[5] Manchin is also among the more isolationist members of the Democratic caucus, having repeatedly called for the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan and having opposed most military interventions in Syria.

As of 2021, Manchin is the only Democrat holding statewide office in West Virginia, as well as the only Democrat in West Virginia's congressional delegation. After the 2020 elections, he became a swing vote in a 50-50 Democratic-controlled Senate.[6] The Democratic Party's marginal majority in the 117th Congress has made Manchin one of its most influential members and possibly the most powerful Senator.[7][8]

Early life and education[]

Manchin was born in 1947 in Farmington, West Virginia, a small coal mining town, the second of five children of Mary O. (née Gouzd) and John Manchin.[9][10] The name "Manchin" was derived from the Italian name "Mancini". His father was of Italian descent and his maternal grandparents were Czechoslovak immigrants.[9][11] He is a member of the Friends of Wales Caucus.[citation needed]

Manchin's father owned a carpet and furniture store, and his grandfather, Joseph Manchin, owned a grocery store.[12] His father and his grandfather both served as Farmington's mayor. His uncle A.J. Manchin was a member of the West Virginia House of Delegates and later the West Virginia Secretary of State and Treasurer.[13]

Manchin graduated from Farmington High School in 1965.[14] He entered West Virginia University on a football scholarship in 1965, but an injury during practice ended his football career. Manchin graduated in 1970 with a degree in business administration[15] and went to work for his family's business.[9]

Manchin has been a close friend of Alabama Crimson Tide football coach Nick Saban since childhood.[16]

Business career[]

Manchin founded the coal brokerage Enersystems in 1988,[17] and helped run it until he became a full-time politician.[18] When he was elected West Virginia secretary of state in 2000, he gave control of Enersystems to his son Joseph. In Manchin’s financial disclosure for 2020, he reported that his non-public shares of Enersystems were worth between $1 million and $5 million, and that the company had paid him $492,000 during the year.[19]

Since his election to the U.S. Senate in 2010, Manchin has listed AA Properties as a non-public asset on his annual financial disclosures.[20][21] AA Property is reportedly 50% controlled by Manchin, and has, among other things, been an investor in Emerald Coast Realty, which owns a La Quinta hotel in Elkview, West Virginia.[22]

Early political career[]

Manchin was elected to the West Virginia House of Delegates in 1982 at age 35 and in 1986 was elected to the West Virginia Senate, where he served until 1996. He ran for governor in 1996, losing the Democratic primary election to Charlotte Pritt. He was elected Secretary of State of West Virginia in 2000.

Governor of West Virginia[]

In 2003 Manchin announced his intention to challenge incumbent Democratic Governor Bob Wise in the 2004 Democratic primary. Wise decided not to seek reelection after a scandal, and Manchin won the Democratic primary and general election by large margins. His election marked the first time since 1964 that a West Virginia governor was succeeded by another governor from the same party.

Manchin was a member of the National Governors Association, the Southern Governors' Association, and the Democratic Governors Association. He was also chairman of the Southern States Energy Board, state's chair of the Appalachian Regional Commission and chairman of the Interstate Mining Compact Commission.

In July 2005, Massey Energy CEO Don Blankenship sued Manchin, alleging that Manchin had violated Blankenship's First Amendment rights by threatening increased government scrutiny of his coal operations in retaliation for Blankenship's political activities.[23] Blankenship had donated substantial funds into campaigns to defeat a proposed pension bond amendment and oppose the reelection of state Supreme Court Justice Warren McGraw,[24] and he fought against a proposed increase in the severance tax on extraction of mineral resources.[25] Soon after the bond amendment's defeat, the state Division of Environmental Protection (DEP) revoked a permit approval for controversial new silos near Marsh Fork Elementary School in Raleigh County. While area residents had complained for some time that the coal operation there endangered their children, Blankenship claimed that the DEP acted in response to his opposition to the bond amendment.[26]

During the Sago Mine disaster in early January 2006 in Upshur County, West Virginia, Manchin confirmed incorrect reports that 12 miners had survived; in actuality only one survived.[27] Manchin later acknowledged that a miscommunication had occurred with rescue teams in the mine.[28] On February 1, 2006, he ordered a stop to all coal production in West Virginia pending safety checks after two more miners were killed in separate accidents.[29] Sixteen West Virginia coal miners died in mining accidents in early 2006. In November 2006, SurveyUSA ranked Manchin one of the country's most popular governors, with a 74% approval rating.[30]

Manchin easily won reelection to a second term as governor in 2008 against Republican Russ Weeks, capturing 69.77% of the vote and winning every county.[31]

U.S. Senate[]

Elections[]

2010[]

Due to Senator Robert Byrd's declining health, there was speculation about what Manchin would do if Byrd died. Manchin refused to comment on the subject until Byrd's death, except to say that he would not appoint himself to the Senate.[32] Byrd died on June 28, 2010,[33] and Manchin appointed Carte Goodwin, his 36-year-old legal adviser, on July 16.[34]

On July 20, 2010, Manchin announced he would seek the Senate seat.[35] In the August 28 Democratic primary he defeated former Democratic Congressman and former West Virginia Secretary of State Ken Hechler.[36] In the general election he defeated Republican businessman John Raese with 54% of the vote.

2012[]

Manchin ran for reelection to a full-term in 2012. According to the Democratic firm Public Policy Polling, early polling found Manchin heavily favored, leading Representative Shelley Moore Capito 50–39, 2010 opponent John Raese 60–31, and Congressman David McKinley 57–28.[37] Manchin did not endorse President Barack Obama for reelection in 2012, saying that he had "some real differences" with the presumptive nominees of both major parties, finding fault with Obama's economic and energy policies and questioning Romney's understanding of the "challenges facing ordinary people."[38]

Manchin defeated Raese and Mountain Party candidate Bob Henry Baber, winning 61% of the vote.[39]

2018[]

In 2018, Manchin ran for reelection.[40] He was challenged in the Democratic primary by Paula Jean Swearengin. Swearengin is an activist and coal miner's daughter who was supported by former members of Bernie Sanders's 2016 presidential campaign. She criticized Manchin for voting with Republicans and supporting Trump's policies.[3][41] Manchin won the primary with 70% of the vote.

On the Republican side, Manchin was challenged by West Virginia Attorney General Patrick Morrisey. In August 2017, Morrisey publicly asked Manchin to resign from the Senate Democratic leadership. Manchin responded, "I don't give a shit, you understand?" to a Charleston Gazette-Mail reporter. "I just don't give a shit. Don't care if I get elected, don't care if I get defeated, how about that?"[42]

Manchin won the November 6 general election, defeating Morrisey 49.57%-46.26%.[43]

Tenure[]

Obama years (2010–2017)[]

Manchin was first sworn in to the U.S. Senate by Vice President Joe Biden on November 15, 2010, succeeding interim Senator Carte Goodwin.[40] In a 2014 New York Times interview, Manchin said his relationship with Obama was "fairly nonexistent."[44]

Trump years (2017–2021)[]

According to FiveThirtyEight, which tracks congressional votes, Manchin voted with Trump's position 50.4% of the time during his presidency.[45]

Manchin initially welcomed Trump's presidency, saying, "He'll correct the trading policies, the imbalance in our trade policies, which are horrible." He supported the idea of Trump "calling companies to keep them from moving factories overseas."[46] Manchin voted for most of Trump's cabinet nominees. He was the only Democrat to vote to confirm Attorney General Jeff Sessions[47] and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin,[48] one of two Democrats to vote to confirm Scott Pruitt as EPA Administrator, and one of three to vote to confirm Secretary of State Rex Tillerson.[49]

Manchin voted for Trump's first two Supreme Court nominees, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh. In the former case, he was one of three Democrats (alongside Joe Donnelly and Heidi Heitkamp) to vote to confirm; in the latter case, he was the only one. He opposed the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett, citing the closeness to the upcoming presidential election.[50]

Manchin voted to convict Trump in both impeachment trials, the second taking place shortly after the inauguration of Joe Biden.

Biden years (2021–present)[]

According to FiveThirtyEight, Manchin has voted with Biden's position 100% of the time as of May 2021.[51] Since the beginning of the Biden administration, the Senate has been evenly divided between Democratic and Republican members; Manchin's ability to deny Democrats a majority has made him very influential.[7][8]

Committee assignments[]

- Committee on Appropriations

- Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies

- Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

- Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies

- Subcommittee on Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies

- Subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related Agencies

- Committee on Energy and Natural Resources (chair)

- As chair of the full committee, Manchin may serve as an ex officio member of all subcommittees.

- Committee on Armed Services

- Committee on Veterans' Affairs

Political positions[]

Manchin is often considered a moderate,[46][52] or even conservative,[46][53] Democrat. He has called himself a "moderate conservative Democrat"[54] and "fiscally responsible and socially compassionate." CBS News has called him "a rifle-brandishing moderate" who is "about as centrist as a senator can get."[55] The American Conservative Union gave him a 25% lifetime conservative rating and the progressive PAC Americans for Democratic Action gave him a 35% liberal quotient in 2016.[56] In February 2018, a Congressional Quarterly study found that Manchin had voted with Trump's position 71% of the time.[57] In 2013, the National Journal gave Manchin an overall score of 55% conservative and 46% liberal.[58]

Abortion[]

Manchin identifies as "pro-life."[59] He has mixed ratings from both abortion-rights and anti-abortion movements political action groups. In 2018, Planned Parenthood, a nonprofit organization that provides reproductive health services, including abortions, gave Manchin a lifetime grade of 57%. National Right to Life (NRLC), which opposes abortion, gave Manchin a 100% score in 2019 and NARAL Pro-Choice America gave him a 72% in 2017.[60] On August 3, 2015, he broke with Democratic leadership by voting in favor of a Republican-sponsored bill to terminate federal funding for Planned Parenthood both in the United States and globally.[61] He has the endorsement of Democrats for Life of America, a pro-life Democratic PAC.[62]

On March 30, 2017, Manchin expressed support for abortion rights by voting against H.J.Res. 43,[63] a bill to allow states to withhold money from abortion providers. Trump signed the bill.[64] In April 2017, Manchin endorsed the continued funding of Planned Parenthood.[65][66] Also in 2017, Planned Parenthood gave him a rating of 44%.[67] In January 2018, Manchin joined two other Democrats and most Republicans by voting for a bill to ban abortion after 20 weeks.[68] In June 2018, upon Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy's retirement, Manchin urged Trump not to appoint a judge who would seek to overturn Roe v. Wade but to instead choose a "centrist."[69]

In 2019, Manchin was one of three Democrats to join all Republicans in voting for a bill to require that doctors care for infants born alive after a failed abortion.[70]

Airports[]

After Manchin and Shelley Moore Capito announced $2.7 million from the Department of Transportation's Essential Air Service program for the North Central West Virginia Airport in October 2019, Manchin called air travel critical for both economic growth and the tourism industry in West Virginia and said that reliable air service to North Central West Virginia "opened up the area to more visitors and new economic opportunities, including an aerospace industry that has generated more than $1 billion worth of economic impact in the surrounding region."[71]

Bipartisanship[]

In his first year in office, Manchin met one-on-one with all 99 of his Senate colleagues in an effort to get to know them better.[72]

On December 13, 2010, Manchin participated in the launch of No Labels, a nonpartisan organization "committed to bringing all sides together to move the nation forward."[73] Manchin is a co-chair of No Labels.[74]

Manchin was one of only three Democratic senators to dissent from Harry Reid's leadership to vote against the nuclear option, which switched the Senate away from operating on a supermajority basis, to requiring only a simple majority for certain decisions, on November 21, 2013.

Manchin worked with Senator Pat Toomey (R-PA) to introduce legislation that would require a background check for most gun sales.[75]

Manchin opposed the January 2018 government shutdown. The New York Times suggested that Manchin helped end the shutdown by threatening not to run for reelection unless his fellow Democrats ended it.[76]

Before his Senate swearing-in in 2010, rumors suggested that the Republican Party was courting Manchin to change parties.[77] Republicans later suggested that Manchin was the source of the rumors,[78] but they attempted to convince him again in 2014 after retaking control of the Senate.[79] He again rejected their overtures.[80] As the 2016 elections approached, reports speculated that Manchin would become a Republican if the Senate were in a 50–50 tie,[81] but he later said he would remain a Democrat at least as long as he remained in the Senate.[82]

Manchin criticized Democrats for not standing for President Trump's 2018 State of the Union Address, saying, "I've seen it on both sides when Obama gave speeches, Republicans. That's disrespectful and last night was disrespectful."[83]

On January 8, 2019, Manchin was one of four Democrats to vote to advance a bill imposing sanctions against the Syrian government and furthering U.S. support for Israel and Jordan as Democratic members of the chamber employed tactics to end the United States federal government shutdown of 2018–2019.[84] In April 2019, he endorsed Republican Senator Susan Collins in her 2020 reelection campaign.[85]

Broadband[]

In December 2018, following the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) announcing a pause on the funding program for wireless broadband during its conduction of an investigation regarding the submission of coverage data by major wireless carriers, Manchin announced his intent to hold the renomination of Brendan Carr in protest of the move. Manchin lifted his hold the following week, after the FCC promised that rolling out funding for wireless broadband in rural areas would be a priority.[86]

In March 2019, Manchin was a cosponsor of a bill that would have included consumer-reported data along with data from state and local governments into consideration during mapping of which areas have broadband and that would take into consideration the measures used to challenge broadband services. Manchin called himself "the only member of Congress to formally challenge a federal broadband coverage map through the Mobility Fund Phase II challenge process" and referred to the bill as "a good first step" in implementing public input in provider data.[87]

In August 2019, Manchin sent FCC Chairman Ajit Pai eight letters that contained results from speed tests across his state of West Virginia as part of an effort to highlight incorrect broadband coverage maps in the state. Manchin opined that "devastating impacts on the tourism industry" in West Virginia were being caused by a lack of broadband access and that the same things that had attracted people to visit West Virginia such as its tall mountains, forests, hills, and rapids had made "broadband deployment astronomically expensive."[88]

China[]

In April 2017, Manchin was one of eight Democratic senators to sign a letter to President Trump noting government-subsidized Chinese steel had been placed into the American market in recent years below cost and had hurt the domestic steel industry and the iron ore industry that fed it, calling on Trump to raise the steel issue with President of the People's Republic of China Xi Jinping in his meeting with him.[89]

In July 2017, he urged Trump to block the sale of the Chicago Stock Exchange to Chinese investors, arguing that China's "rejection of fundamental free-market norms and property rights of private citizens makes me strongly doubt whether an Exchange operating under the direct control of a Chinese entity can be trusted to 'self-regulate' now and in the future." He also expressed concern "that the challenges plaguing the Chinese market – lack of transparency, currency manipulation, etc. – will bleed into the Chicago Stock Exchange and adversely impact financial markets across the country."[90]

In November 2017, in response to efforts by China to purchase tech companies based in the US, Manchin was one of nine senators to cosponsor a bill that would broaden the federal government's ability to prevent foreign purchases of U.S. firms through increasing the strength of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). The scope of the CFIUS would be expanded to allow it to review along with possibly decline smaller investments and add additional national security factors for CFIUS to consider including if information about Americans would be exposed as part of transactions or whether the deal would facilitate fraud.[91]

In November 2017, following the West Virginia Commerce Department announcing an agreement with China Energy to invest $83.7 billion in shale gas development and chemical manufacturing projects in West Virginia after state Commerce Secretary Woody Thrasher and China Energy President Ling Wen signed a Memorandum of Understanding, Manchin said that he was thrilled with the signing and that he was satisfied that China Energy recognized West Virginians as the hardest working people in the world.[92]

In March 2018, Manchin cited China as responsible for President Trump's imposing of tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, noting that the United States was the largest importer of steel while 50 percent of steel was produced in China, and that he did believe the theory that prices would increase as a result of the tariffs.[93]

In May 2019, Manchin was a cosponsor of the South China Sea and East China Sea Sanctions Act, a bipartisan bill reintroduced by Marco Rubio and Ben Cardin that was intended to disrupt China's consolidation or expansion of its claims of jurisdiction over both the sea and air space in disputed zones in the South China Sea.[94]

D.C. and Puerto Rico statehood[]

In a November 10, 2020, interview, Manchin said that he did not "see the need for the D.C. statehood with the type of services that we're getting in D.C. right now" and that he was "not convinced that's the way to go." Of Puerto Rico statehood, Manchin said that he opposed it but was open to discussion.[95] In a January 10, 2021 interview, he did not affirm his opposition to statehood for D.C. or Puerto Rico, saying only, "I don't know enough about that yet. I want to see the pros and cons. So I'm waiting to see all the facts. I'm open up to see everything".[96] On April 30, 2021, Manchin came out against the D.C. Statehood bill that had passed the House of Representatives, suggesting that D.C. could instead be given statehood by constitutional amendment.[97]

Disaster relief[]

In May 2019, Manchin and John Cornyn introduced the Disaster Recovery Funding Act, a bill that would direct the Office of Management and Budget to release $16 billion for disaster relief funding within 60 days to nine states and two U.S. Territories. Manchin said that West Virginia had been awaiting funding for rebuilding for three years since a series of floods in June 2016 and that he was proud to work with Cornyn on a bipartisan solution.[98]

In August 2019, as Manchin announced $106 million in disaster relief funding for West Virginia, he said the Trump administration had finally heeded his request by releasing "this desperately needed funding to the people of West Virginia and other areas of the country that are still rebuilding and recovering from horrible natural disasters", and promoted the funding as helping West Virginia "rebuild smarter and stronger and reduce the potential future catastrophic flooding in this area."[99]

Dodd-Frank[]

In 2018, Manchin was one of 17 Democrats to break with their party and vote with Republicans to ease the Dodd-Frank banking rules.[100]

Drugs[]

It has been suggested that portions of Joe Manchin (Heather Bresch) be split from it and merged into this section. (Discuss) (April 2019) |

In June 2011, Manchin joined Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY) in seeking a crackdown on Bitcoin currency transactions, saying that they facilitated illegal drug trade transactions. "The transactions leave no traditional bank transfer money trail for investigators to follow, and leave it hard to prove a package recipient knew in advance what was in a shipment," using an "'anonymizing network' known as Tor."[101] One opinion website said the senators wanted "to disrupt the Silk Road drug website."[102]

In May 2012, in an effort to reduce prescription drug abuse, Manchin successfully proposed an amendment to the Food and Drug Administration reauthorization bill to reclassify hydrocodone as a Schedule II controlled substance.[103]

In March 2017, Manchin was one of 21 senators to sign a letter led by Ed Markey to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell that noted that 12% of adult Medicaid beneficiaries had some form or a substance abuse disorder and that one third of treatment for opioid and other substance use disorders in the United States is financed through Medicaid, and opined that the American Health Care Act could "very literally translate into a death spiral for those with opioid use disorders" due to the insurance coverage lacking adequate funds for care, often resulting in individuals abandoning substance use disorder treatment.[104]

Education[]

In February 2019, Manchin said the collapse of an omnibus education reform proposal resulted from state lawmakers not laying groundwork for broad support for the proposal, saying, "You don’t do major reform, policy changes, for the whole education system in a 60-day session without public hearings. There should have been a whole year of going out and speaking to the public." He stated his support for home school and private school as well as his opposition to funding "them with public dollars."[105]

In a September 2019 letter to United States Secretary of Education Betsy Devos, Manchin noted that the West Virginia Education Department had identified over 10,000 children as "homeless for the 2018-2019 school year" and argued that West Virginia was receiving insufficient resources through the McKinney-Vento program and a Title I program.[106]

Energy and environment[]

Manchin sits on the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee and supports a comprehensive, all-of-the-above energy approach that includes coal.[107]

Manchin's first bill in the Senate dealt with what he called the EPA's overreach. After the EPA vetoed a previously approved permit for the Spruce Mine in Logan County, West Virginia, he offered the EPA Fair Play Act,[108] which would "clarify and confirm the authority of the Environment Protection Agency to deny or restrict the use of defined areas as disposal sites for the discharge of dredged or filled material."[109] Manchin said the bill would prevent the EPA from "changing its rules on businesses after permits have already been granted."[110]

On October 6, 2010, Manchin directed a lawsuit aimed at overturning new federal rules concerning mountaintop removal mining. Filed by the state Department of Environmental Protection, the lawsuit "accuses U.S. EPA of overstepping its authority and asks the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of West Virginia to throw out the federal agency's new guidelines for issuing Clean Water Act permits for coal mines." In order to qualify for the permits, mining companies need to prove their projects would not cause the concentration of pollutants in the local water to rise five times above the normal level. The New York Times reported that EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson said the new legislation would protect 95% of aquatic life by banning operators from dumping mine waste into streams.[111]

Environmentalists have criticized Manchin for his family ties to the coal industry. He served as president of Energysystems in the late 1990s before becoming active in politics. On his financial disclosures in 2009 and 2010, his reported earnings from the company were $1,363,916 and $417,255, respectively.[112] Critics have said his opposition to health regulations that would raise industry expenses are due to his stake in the industry; West Virginia's Sierra Club chapter chair Jim Sconyers said, "he's been nothing but a mouthpiece for the coal industry his whole public life."[112] Opinions on the subject are mixed; The Charleston Gazette wrote, "the prospect that Manchin's $1.7 million-plus in recent Enersystems earnings might tilt him even more strongly pro-coal might seem remote, given the deep economic and cultural connections that the industry maintains in West Virginia."[113]

On November 14, 2011, Manchin chaired his first field hearing of that committee in Charleston, West Virginia, to focus on Marcellus Shale natural gas development and production. He said, "We are literally sitting on top of tremendous potential with the Marcellus shale. We need to work together to chart a path forward in a safe and responsible way that lets us produce energy right here in America."[114]

Manchin supports building the Keystone XL Pipeline from Canada. He has said, "It makes so much common sense that you want to buy oil off your friends and not your enemies." The pipeline would span over 2,000 miles across the United States.[115]

On November 9, 2011, Manchin and Dan Coats introduced the Fair Compliance Act. The bill would "lengthen timelines and establish benchmarks for utilities to comply with two major Environmental Protection Agency air pollution rules. The legislation would extend the compliance deadline for the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule, or CSAPR, by three years and the deadline for the Utility MACT rule by two years—setting both to January 1, 2017."[116]

Manchin and John Barrasso introduced the American Alternative Fuels Act on May 10, 2011. The bill would remove restrictions on development of alternative fuels, repeal part of the 2007 energy bill restricting the federal government from buying alternative fuels and encourage the development of algae-based fuels and synthetic natural gas. Of the bill, Manchin said, "Our unacceptably high gas prices are hurting not only West Virginians, but all Americans, and they underscore a critical need: the federal government needs to be a partner, not an obstacle, for businesses that can transform our domestic energy resources into gas."[117]

In 2011, Manchin was the only Democratic senator to support the Energy Tax Prevention Act, which sought to prohibit the EPA from regulating greenhouse gas.[118] He was also one of four Democratic senators to vote against the Stream Protection Rule.[119] In 2012, Manchin supported a GOP effort to "scuttle Environmental Protection Agency regulations that mandate cuts in mercury pollution and other toxic emissions from coal-fired power plants", while West Virginia's other senator, Jay Rockefeller, did not.[120]

In December 2014, Manchin was one of six Democratic senators to sign a letter to the EPA urging it to give states more time to comply with its rule on power plants because the final rule "must provide adequate time for the design, permitting and construction of such large scale capital intensive infrastructure", and calling for an elimination of the 2020 targets in the final rule, a mandate that states take action by 2020 as part of the EPA's goal to reach a 30% carbon cut by 2030.[121]

Manchin criticized Obama's environmental regulations as a "war on coal" and demanded what he called a proper balance between the needs of the environment and the coal business.[122] The Los Angeles Times wrote that while professing environmental concerns, he has consistently stood up for coal, saying "no one is going to stop using fossil fuels for a long time." Manchin "does not deny the existence of man-made climate change", the Times wrote, but "is reluctant to curtail it."[123] In February 2017, he was one of two Democratic senators to vote to confirm Scott Pruitt as Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency.[124] In June 2017, Manchin supported Trump's withdrawal from the Paris climate accord, saying he supported "a cleaner energy future" but that the Paris deal failed to strike "a balance between our environment and the economy."[125]

In June 2017, Manchin introduced the Capitalizing American Storage Potential Act, legislation ensuring a regional storage hub would qualify for the Title XVII innovative technologies loan guarantee program of the Energy Department. He argued the Appalachian Storage Hub would grant West Virginia and its neighboring states the ability "to realize the unique opportunities associated with Appalachia’s abundant natural gas liquids like ethane, naturally occurring geologic storage and expanding energy infrastructure" and that the regional storage hub would "attract manufacturing investment, create jobs and significantly reduce the rejection rate of natural gas liquids." The Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee approved the bill in March 2018.[126]

In April 2018, Manchin and Capito introduced the Electricity Reliability and Fuel Security Act, a bill providing a temporary tax credit for existing coal-fired power plants that would help cover a part of both operation and maintenance costs. Manchin said that he knew "coal-fired power" was the engine of the West Virginia economy and that "coal-fired power plants have kept the lights on when other forms of energy could not".[127]

In July 2018, along with fellow Democrat Heidi Heitkamp and Republicans James Risch and Lamar Alexander, Manchin introduced the Recovering America's Wildlife Act, a bill that would reallocate $1.3 billion annually from energy development on federal lands and waters to the Wildlife Conservation Restoration Program intended to conserve fish and wildlife.[128]

In February 2019, in response to reports that the EPA intended to decide against setting drinking water limits for perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) as part of a national strategy to manage those chemicals, Manchin was one of 20 senators to sign a letter to Acting EPA Administrator Andrew R. Wheeler calling on the EPA "to develop enforceable federal drinking water standards for PFOA and PFOS, as well as institute immediate actions to protect the public from contamination from additional per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)."[129] In April 2019, he was one of three Democratic Senators who voted with Republicans to confirm David Bernhardt, an oil executive, as Secretary of the Interior Department.[130]

In February 2019, after Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell called for a vote on the Green New Deal in order to get Democratic members of the Senate on record regarding the legislation, Manchin expressed opposition to the plan:

"The Green New Deal is a dream, it's not a deal. It's a dream. And that's fine. People should have dreams in the perfect world what they'd like to see. I've got to work in realities and I've got to work in the practical, what I have in front of me. I've got to make sure that our country has affordable, dependable, reliable energy 24/7, but you can't just be a denier and say, 'Well, I'm not going to use coal. I'm not going to use natural gas. I'm not going to use oil.'"[131]

In April 2019, Manchin was one of 12 senators to sign a bipartisan letter to top senators on the Appropriations Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development advocating that the Energy Department be granted maximum funding for carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS), arguing that American job growth could be stimulated through investment in viable options to capture carbon emissions and expressing disagreement with Trump's 2020 budget request to combine the two federal programs that include carbon capture research.[132]

In April 2019, Manchin was the only Democrat to cosponsor the Enhancing Fossil Fuel Energy Carbon Technology (EFFECT) Act, legislation intended to increase federal funding for developing carbon capture technology and simultaneously commit to fossil fuel use. In a statement, he cited the need for the United States "to lead in technological innovations designed to reduce carbon emissions" while noting that energy experts who had testified before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources had concurred on the continued use of fossil fuels through 2040. He called the bill "a critical piece of the solution addressing the climate crisis."[133]

In April 2019, Manchin was the lead sponsor the Land and Water Conservation Fund Permanent Funding Act, bipartisan legislation that would provide permanent and dedicated funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) at a level of $900 million as part of an effort to protect public lands.[134]

In May 2019, Manchin, Lisa Murkowski and Martha McSally introduced the American Mineral Security Act, a bill that would codify current methodology that the United States used to list critical minerals and require the list to be updated at least once every three years. McSally's office also said the bill would mandate nationwide resource assessments for every critical mineral.[135]

In September 2019, Manchin was one of eight senators to sign a bipartisan letter to congressional leadership requesting full and lasting funding of the Land and Water Conservation Act in order to aid national parks and public lands, benefit the $887 billion American outdoor recreation economy, and "ensure much-needed investment in our public lands and continuity for the state, tribal, and non-federal partners who depend on them."[136]

In February 2021, Manchin was one of seven Democratic U.S. Senators to join Republicans in blocking a ban of hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as fracking.[137]

Federal budget[]

Manchin has co-sponsored balanced budget amendments put forth by Senators Mike Lee (R-UT),[138] Richard Shelby (R-AL), and Mark Udall (D-CO).[139] He has also voted against raising the federal debt ceiling.[140]

Manchin has expressed strong opposition to entitlement reform, describing Mitch McConnell's comments in October 2018 on the need to reform entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicaid and Medicare as "absolutely ridiculous."[141] In January 2019, Manchin supported both Republican and Democratic bills to end a government shutdown.[142] He was the only Democrat to break from his party and vote in favor of the Republican proposal.[143]

On August 1, 2019, the Senate passed a bipartisan budget deal that raised spending over current levels by $320 billon and lifted the debt ceiling for the following two years in addition to forming a course for funding the government without the perceived fiscal brinkmanship of recent years. Manchin joined Tom Carper and Republicans Mitt Romney and Rick Scott in issuing a statement asserting that "as former Governors, we were responsible for setting a budget each year that was fiscally responsible to fund our priorities. That’s why today, we, as U.S. Senators, cannot bring ourselves to vote for this budget deal that does not put our country on a fiscally sustainable path."[144]

Foreign policy[]

Manchin is critical of American military intervention overseas, particularly in Afghanistan and Syria. He has repeatedly demanded the withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan and has opposed most military intervention in Syria.[145][146][147][148]

On June 21, 2011, Manchin delivered a speech on the Senate floor calling for a "substantial and responsible reduction in the United States' military presence in Afghanistan." He said, "We can no longer afford to rebuild Afghanistan and America. We must choose. And I choose America."[149] Manchin's remarks were criticized by Senator John McCain (R-AZ) as "at least uninformed about history and strategy and the challenges we face from radical Islamic extremism."[146] Manchin made similar remarks in a press conference on January 7, 2014, arguing that "all of the money and all of the military might in the world will not change that part of the world." He said that by the end of the year, the American troops in that country should be at Bagram Airfield alone.[145] After the deaths of three American soldiers in Afghanistan in November 2018, Manchin renewed his calls for the withdraw of American troops from the country, saying that both presidents Obama and Trump had expressed support for taking troops out of the country but had not done so. "They all seem to have the rhetoric, and no one seems to have the follow up. It's time to come out of there," he said.[146]

Manchin introduced legislation to reduce the use of overseas service and security contractors. He successfully amended the 2013 National Defense Authorization Act to cap contractors' taxpayer-funded salaries at $230,000.[150]

Following the Ghouta chemical attack in August 2013 during the Syrian Civil War, Manchin said, "There is no doubt that an attack occurred and there is no doubt it was produced under the Assad regime. It's not clear cut if Assad gave the order himself. It has not been proven." He opposed any strikes on the Syrian Government in retaliation for the attacks. Instead, he introduced a joint resolution with Senator Heidi Heitkamp (D-ND) requesting that President Obama come up with a long-term strategy on Syria and work diplomatically to ensure the destruction of Syria's chemical weapons.[147] On September 16, 2014, Manchin announced that he would vote against a possible Senate resolution to arm Syrian opposition fighters. "At the end of the day, most of the arms that we give to people are used against us. Most of the people we train turn against us," he said. He referred to plans calling for ground troops in Syria, which had been proposed by some Republican senators, including Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, as "insanity,"[148] but supported the 2017 Shayrat missile strike launched by order of President Trump in response to a chemical weapons attack allegedly perpetrated by the Syrian Government. Manchin said that "yesterday's strike was important to send a message to the Syrian regime and their Russian enablers that these horrific actions will not be tolerated."[151]

In April 2017, following a North Korea senior official declaring that the U.S. had created "a dangerous situation in which a thermonuclear war may break out at any minute," Manchin stated that North Korea had "to understand that we will retaliate" and that he did not believe the U.S. would not respond if North Korea continued to play "their games."[152] In May 2018, Manchin accused Kim Jong-un of accelerating "the nuclear threat" of North Korea in a manner that would enable him to receive concessions and that Kim Jong-un was "in a serious, serious problem with his country and the people in his country" without China.[153]

In June 2017, Manchin was one of five Democrats who, by voting against a Senate resolution disapproving of arms sales to Saudi Arabia, ensured its failure. Potential primary opponent Paula Jean Swearengin charged that because of Manchin's vote, weapons sold to the Saudis "could possibly end up in the hands of terrorists."[154]

In June 2017, Manchin co-sponsored the Israel Anti-Boycott Act (S.270), which made it a federal crime, punishable by a maximum sentence of 20 years imprisonment,[155] for Americans to encourage or participate in boycotts against Israel and Israeli settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories if protesting actions by the Israeli government.[156]

In 2019, Manchin and Republican Marco Rubio drafted a Middle East policy bill with provisions that rebuked President Trump over withdrawals of troops from Syria and Afghanistan and a measure authorizing state and municipal governments to punish companies after they oppose Israel via boycott, divestment or sanctions. The measure also reauthorized at least $3.3 billion for Israel's military financing in addition to extending Jordan's security aid, granting new sanctions on individuals giving their support to the Syrian government and ordering the Treasury Department to determine whether the Central Bank of Syria was money laundering. The bill passed in the Senate in a 77 to 23 vote in February 2019.[157]

In October 2019, Manchin was one of six senators to sign a bipartisan letter to Trump calling on him to "urge Turkey to end their offensive and find a way to a peaceful resolution while supporting our Kurdish partners to ensure regional stability" and arguing that to leave Syria without installing protections for American allies would endanger both them and the US.[158]

Guns[]

In 2012 Manchin's candidacy was endorsed by the National Rifle Association (NRA), which gave him an "A" rating.[159] Following the Sandy Hook shooting, Manchin partnered with Republican senator Pat Toomey to introduce a bill that would have strengthened background checks on gun sales. The Manchin-Toomey bill was defeated on April 17, 2013, by a vote of 54–46; 60 votes would have been required to pass it.[75] Despite the fact that the bill did not pass, the NRA targeted Manchin in an attack ad.[160][161][162]

Manchin was criticized in 2013 for agreeing to an interview with The Journal in Martinsburg, West Virginia, but demanding that he not be asked any questions about gun control or the Second Amendment.[163]

In 2016, referring to the difficulty of keeping guns out of the hands of potential terrorists in the aftermath of the Orlando nightclub shooting, Manchin said, "due process is what's killing us right now." This comment drew the criticism of both the NRA and the Cato Institute, which accused Manchin of attacking a fundamental constitutional principle. "With all respect," commented Ilya Shapiro of Cato, "due process is the essential basis of America."[164][165]

In October 2017, following the Las Vegas shooting, Manchin stated that it was "going to take President Trump, who looks at something from a law-abiding gun owner’s standpoint, that makes common sense and gun sense" for progress to be made on gun legislation and that he would not rule out reviving the Manchin-Toomey bill if the legislation attracted enough Republican cosponsors.[166]

In a March 2018 interview, a month after the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting and shortly before the March For Our Lives demonstrations, Manchin stated that the Manchin-Toomey bill should serve as the base for a new gun control law and that Trump expressing support for background checks would set his legacy and "give Republicans enough cover to support this in the most reasonable, responsible way."[167]

In August 2019, following two more mass shootings in El Paso, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio, Manchin said that Trump had "a golden opportunity to start making America safe again by starting with this basic building block of background checks." Manchin also noted his disagreement with the position of House Minority Whip Steve Scalise that existing gun background check measures were sufficient, adding that even though he was "a law-abiding gun owner," he would not sell a gun through a gun show or online to someone whose history he was unsure of.[168] On September 5 of that year, Manchin and Trump met in the White House for a discussion on gun-control legislation. According to a White House official, Trump told Manchin of his "interest in getting a result" so dialogue could resume "to see if there’s a way to create a reasonable background check proposal, along with other ideas."[169]

Health care[]

In 2010, Manchin called for "repairs" of the Affordable Care Act and repeal of the "bad parts of Obamacare."[170][171] On January 14, 2017, Manchin expressed concern at the strict party-line vote on repealing Obamacare and said he could not, in good conscience, vote to repeal without a new plan in place. He added, however, that he was willing to work with Trump and the GOP to formulate a replacement.[172] In June 2017, Manchin and Bob Casey Jr. of Pennsylvania warned that repealing Obamacare would worsen the opioid crisis.[173] In July 2017, he said that he was one of about ten senators from both parties who had been "working together behind the scenes" to formulate a new health-care program, but that there was otherwise insufficient bipartisanship on the issue.[174]

In September 2017, Manchin released a statement expressing that he was skeptical of a single-payer health care system being "the right solution" while noting his support for the Senate considering "all of the options through regular order so that we can fully understand the impacts of these ideas on both our people and our economy."[174]

During 2016–17, Manchin read to the Senate several letters from constituents about loved ones' deaths from opioids and urged his colleagues to act to prevent more deaths. Manchin took "an unusual proposal" to President Trump to address the crisis and called for a "war on drugs" that involves not punishment but treatment. He proposed the LifeBOAT Act, which would fund treatment. He also opposes marijuana legalization.[175][176] In January 2018, Manchin was one of six Democrats who broke with their party to vote to confirm Trump's nominee for Health Secretary, Alex Azar.[177]

In his 2018 reelection campaign, Manchin emphasized his support for Obamacare, running an ad where he shot holes in a lawsuit that sought to repeal the Affordable Care Act.[171]

In January 2019, Manchin was one of six Democratic senators to introduce the American Miners Act of 2019, a bill that would amend the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 to swap funds in excess of the amounts needed to meet existing obligations under the Abandoned Mine Land fund to the 1974 Pension Plan as part of an effort to prevent its insolvency as a result of coal company bankruptcies and the 2008 financial crisis. It also increased the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund tax and ensured that miners affected by the 2018 coal company bankruptcies would not lose their health care.[178]

In a May 2019 letter to Attorney General William Barr, Manchin and Republican Susan Collins wrote that the Affordable Care Act "is quite simply the law of the land, and it is the Administration's and your Department's duty to defend it" and asserted that Congress could "work together to fix legislatively the parts of the law that aren't working" without letting the position of a federal court "stand and devastate millions of seniors, young adults, women, children and working families."[179]

In September 2019, amid discussions to prevent a government shutdown, Manchin was one of six Democratic senators to sign a letter to congressional leadership advocating for the passage of legislation that would permanently fund health care and pension benefits for retired coal miners as "families in Virginia, West Virginia, Wyoming, Alabama, Colorado, North Dakota and New Mexico" would start to receive notifications of health care termination by the end of the following month.[180]

In October 2019 Manchin was one of 27 senators to sign a letter to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer advocating the passage of the Community Health Investment, Modernization, and Excellence (CHIME) Act, which was set to expire the following month. The senators warned that if the funding for the Community Health Center Fund (CHCF) was allowed to expire, it "would cause an estimated 2,400 site closures, 47,000 lost jobs, and threaten the health care of approximately 9 million Americans."[181]

Homelessness[]

When Manchin and Capito announced over $3.3 million to combat child homelessness in West Virginia in October 2019, Manchin reported that there were at least 10,500 homeless children and youth in West Virginia and pledged to continue working to get financial aid for West Virginia children in his capacity as a member of the Senate Appropriations Committee.[182]

Housing[]

In April 2019, Manchin was one of 41 senators to sign a bipartisan letter to the housing subcommittee praising the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development's Section 4 Capacity Building program for authorizing "HUD to partner with national nonprofit community development organizations to provide education, training, and financial support to local community development corporations (CDCs) across the country" and expressing disappointment that President Trump's budget "has slated this program for elimination after decades of successful economic and community development." The senators wrote of their hope that the subcommittee would support continued funding for Section 4 in Fiscal Year 2020.[183]

Immigration[]

Manchin is opposed to the DREAM Act, and was absent from a 2010 vote on the bill.[184] Manchin supports the construction of a wall along the southern border of the United States.[185][186] He opposed the Obama administration's lawsuit against Arizona over that state's immigration enforcement law.[187] Manchin voted against the McCain-Coons proposal to create a pathway to citizenship for some undocumented immigrants without funding for a border wall and he voted against a comprehensive immigration bill proposed by Susan Collins which gave a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers as well as funding for border security; he voted 'yes' to withholding funding for 'sanctuary cities' and he voted in support of President Trump's proposal to give a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers, build a border wall, and reduce legal immigration.[188][189] On June 18, 2018, he came out against the Trump administration family separation policy.[190] In September 2019, Manchin was the only Democrat on the Senate Appropriations panel to vote for a $71 billion homeland security measure that granted Trump the $5 billion he had previously requested to build roughly 200 miles of fencing along the U.S.-Mexico border.[191]

Manchin has mixed ratings from political action committees opposed to illegal immigration; NumbersUSA, which seeks to reduce illegal and legal immigration, gave Manchin a 55% rating and the Federation for American Immigration Reform, which also seeks to reduce legal immigration, gave him a 25% rating.[192]

On February 4, 2021, Manchin voted against providing COVID-19 pandemic financial support to undocumented immigrants.[193]

Infrastructure[]

In response to a leaked story that the Biden administration would pursue a $3 trillion infrastructure package,[194] Manchin appeared to support the spending, calling for an "enormous" infrastructure bill.[195] He also expressed openness to paying for the bill by raising taxes on corporations and wealthy people, despite the fact that this would likely eliminate any possible bipartisan support.[196][197]

LGBT rights[]

On December 9, 2010, Manchin was the sole Democrat to vote against cloture for the 2011 National Defense Authorization Act, which contained a provision to repeal Don't Ask, Don't Tell. In an interview with The Associated Press, Manchin cited the advice of retired military chaplains as a basis for his decision to vote against repeal.[198] He also indicated he wanted more time to "hear the full range of viewpoints from the citizens of West Virginia."[199] A day later, he was publicly criticized at a gay rights rally for his position on the bill.[200] On July 26, 2017, he came out against Trump's proposed ban on transgender service in the United States military.[201]

As of 2015, Manchin was the only member of the Senate Democratic Caucus to oppose same-sex marriage.[202] He is the only Democratic senator to not have declared support for same-sex marriage.[203][204] On February 14, 2018, he cosponsored S.515, a bill that would amend the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 to clarify that all provisions shall apply to legally married same-sex couples in the same manner as other married couples.[205] As of March 18, 2019, he is the only member of the Senate Democratic Caucus who is not a cosponsor of the Equality Act. He has said that he believes “no one should be afraid of losing their job or losing their housing because of their sexual orientation” but does not believe the current version of the Equality Act "provides sufficient guidance to the local officials who will be responsible for implementing it."[202] In March 2021, Manchin was the only Democrat to vote for a failed amendment to rescind funding from public schools that allow trans youth to participate in the sporting teams of their gender identity.[206][207]

The Human Rights Campaign, the largest LGBT rights group in America, gave Manchin a score of 48% in the 116th Congress.[208] He received a score of 30% in the 115th Congress, 85% in the 114th Congress, and 65% in the 113th Congress.

Minimum wage[]

On February 2, 2021, Manchin announced his opposition to an increase from $7.25 to $15 per hour in the federal minimum wage, but said he was open to a smaller increase, perhaps to $11.[209] He opposed a minimum wage increase as part of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 and forced Democrats to limit extended unemployment benefits in the same bill.[210]

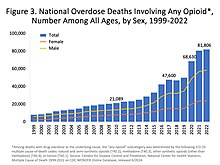

Opioids[]

In December 2017, in a letter to then-Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, Manchin called for changes in the FDA's response to the opioid crisis including mandatory and continuing education for healthcare providers, reviewing every opioid product on the market, and removing an older opioid from the market for every new opioid approved. Manchin cited the over 33,000 deaths in the United States from opioid overdoses in 2015 and over 700 deaths of West Virginians from opioid overdoses in 2016 as his reason for supporting the establishment of the Opioid Policy Steering Committee by the FDA.[211]

In 2018, Manchin secured a provision in the Opioid Crisis Response Act that ensured additional opioid funding for West Virginia after the bill had previously granted funding based on states’ overall opioid overdose death counts as opposed to the overdose death rate. Manchin stated that the bill before his intervention was "basically using a blanket before when giving money" and added that the bill was incentivizing "companies to do the research to produce a product that gives the same relief as the opioid does, but is not (addictive)." The bill passed in the Senate in September.[212]

In April 2019, Manchin cosponsored the Protecting Jessica Grubb's Legacy Act, legislation that authorized medical records of patients being treated for substance use disorder being shared among healthcare providers in the event that the patient provided the information. Cosponsor Shelley Moore Capito stated that the bill also prevented medical providers from unintentionally providing opioids to individuals in recovery.[213]

In May 2019, when Manchin and Capito announced 600,000 of funding for West Virginia through the Rural Communities Opioid Response Program of the Department of Health and Human Services' Health Resources and Services Administration, Manchin stated that the opioid epidemic had devastated every community in West Virginia and that as a senator "fighting against this horrible epidemic and helping fellow West Virginians have always been my top priorities."[214]

In July 2019, Manchin issued a release in which he called for a $1.4 billion settlement from Reckitt Benckiser Group to be used for both programs and resources that would address the opioid epidemic.[215]

Senior citizens[]

To help locate missing senior citizens, Manchin introduced the Silver Alert Act in July 2011 to create a nationwide network for locating missing adults and senior citizens modeled after the AMBER Alert.[216] Manchin also sponsored the National Yellow Dot Act to create a voluntary program that would alert emergency services personnel responding to car accidents of the availability of personal and medical information on the car's owner.[217]

Manchin said in 2014 that he "would change Social Security completely. I would do it on an inflationary basis, as far as paying into payroll taxes, and change that, to keep us stabilized as far as cash flow. I'd do COLAs—I'd talk about COLA for 250 percent of poverty guidelines." Asked whether this meant he would "cut benefits to old people," Manchin said that "a rich old person ... won't get the COLAs." He asked: "Do you want chained CPI? I can live with either one."[218]

Taxes[]

Manchin opposed Trump's Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. He called it "a closed process" that "makes little impact in the paychecks of the people in his state." At the same time, he posited the bill contains "some good things ... Initially people will benefit," although ultimately voting against it. In turn, NRSC spokesman Bob Salera stated that he had "turned his back and voted with Washington Democrats."[219][220]

In March 2019, Manchin was a cosponsor of a bipartisan bill to undo a drafting error in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that mandated stores and restaurants to have to write off the costs of renovations over the course of 39 years via authorizing businesses to immediately deduct the entirety of costs of renovations.[221]

Veterans[]

In February 2017, along with Republican Roy Blunt, Manchin introduced the HIRE Veterans Act, legislation that would recognize qualified employers in the event that they met particular criteria designed to encourage businesses that were friendly toward veterans including calculating what new hire or overall workforce percentages contain veterans, the availability of particular types of training and leadership development opportunities, and other factors that showed commitment on the part of an employer to offer support for veterans after their military careers. The bill passed in the Senate in April, which Manchin applauded in a press release as "tremendous news" given that the bill was "one more step we can take toward making it easier for our service men and women to find opportunities for good-paying jobs."[222]

In December 2018, Manchin was one of twenty-one senators to sign a letter to United States Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert Wilkie calling it "appalling that the VA is not conducting oversight of its own outreach efforts" in spite of suicide prevention being the VA's highest clinical priority and requesting Wilkie "consult with experts with proven track records of successful public and mental health outreach campaigns with a particular emphasis on how those individuals measure success."[223]

In January 2019, Manchin was one of five senators to cosponsor the VA Provider Accountability Act, a bipartisan bill meant to amend title 38 of the United States Code to authorize the under secretary of health to report "major adverse personnel actions" related to certain health care employees at the National Practitioner Data Bank along with applicable state licensing boards. Manchin stated that efforts by the VA were not enough and called for strict guidelines to be implemented in order to ensure veterans "are receiving the highest quality of care, and I believe our legislation provides a fix that can be supported by my colleagues on both sides of the aisle."[224]

In July 2019, Manchin and Republican Marsha Blackburn introduced the Providing Veterans Access to In-State Tuition Act, a bill that would remove a three-year post-discharge requirement and thereby enable student veterans eligibility to receive in-state tuition rates from public schools in the event they decide to use their Post 9/11 GI Bill benefits.[225]

In August 2019, when Manchin and Capito announced a collection of grants that totaled to over $7 million intended to aid homeless veterans under the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) Program, Manchin opined that the funding would "help veterans secure housing, which in turn helps them secure steady jobs and gives them another opportunity to contribute to their communities."[226]

Voting rights[]

On June 6, 2021, in an op-ed published in the Charleston Gazette-Mail, Manchin expressed his opposition to the For the People Act due to its lack of bipartisan support. But he has expressed his support for a reinforced version of the John Lewis Voting Rights Act and urged its passage in the Senate.[227][228] Shortly thereafter, several Democratic lawmakers accused Manchin of supporting Jim Crow laws by opposing the For the People Act, a signature piece of legislation of the Democratic majority, aiming to expand voting rights, among other provisions.[229]

The bill has universal Republican opposition, and so would require the filibuster to be eliminated in order to pass. Manchin defended his opposition to it, saying, "I think there's a lot of great things in that piece of legislation, but there's an awful lot of things that basically don't pertain directly to voting." In the op-ed, he also elaborated on his view of eliminating the filibuster: "I cannot explain strictly partisan election reform or blowing up the Senate rules to expedite one party's agenda."[228]

Personal life[]

Manchin is a member of the National Rifle Association and a licensed pilot.[9][230][231] On August 5, 1967, he married Gayle Heather Conelly. Together they have three children: Heather Manchin Bresch (who was chief executive officer (CEO) of Netherlands-based pharmaceutical company Mylan), Joseph IV, and Brooke.[9]

He is Catholic.[232]

In 2006 and 2010, Manchin delivered commencement addresses at Wheeling Jesuit University and at Davis & Elkins College,[citation needed] receiving honorary degrees from both institutions.[233][234]

In December 2012, Manchin voiced his displeasure with MTV's new reality show Buckwild, set in his home state's capital Charleston, and asked the network's president to cancel the show, which, he argued, depicted West Virginia in a negative, unrealistic fashion.[235] The show ended after its first season.[236]

In a lawsuit filed in July 2014, John Manchin II, one of Manchin's brothers, sued Manchin and his other brother, Roch Manchin, over a $1.7 million loan. The lawsuit alleged that Joe and Roch Manchin borrowed the money to keep the doors open at the family-owned carpet business run by Roch, that no part of the loan had yet been repaid, and that the defendants had taken other measures to evade compensating John Manchin II for non-payment.[237] John Manchin II withdrew the suit on June 30, 2015.[238]

Electoral history[]

1982

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin, III | 7,687 | 21.15% | |

| Democratic | Cody A. Starcher (incumbent) | 6,844 | 18.83% | |

| Democratic | William E. Stewart | 6,391 | 17.59% | |

| Democratic | Samuel A. Morasco | 4,250 | 11.70% | |

| Democratic | Nick Fantasia | 5,072 | 13.96% | |

| Democratic | Donald L. Smith | 3,276 | 9.02% | |

| Democratic | J. Lonnie Bray | 2,819 | 7.76% | |

| Total votes | 36,339 | 100.0% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 16,160 | N/A | |

| Democratic | Cody A. Starcher (incumbent) | 16,110 | N/A | |

| Democratic | William E. Stewart | 15,090 | N/A | |

| Republican | Benjamin N. Springston (incumbent) | 12,166 | N/A | |

| Republican | Paul E. Prunty (incumbent) | 14,620 | N/A | |

| Democratic | Samuel A. Morasco | 11,741 | N/A | |

| Republican | Edgar L. Williams III | 5,702 | N/A | |

| Republican | Lyman Clark | 5,270 | N/A | |

| Democratic hold | ||||

1986

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin, III | 10,691 | 56.53% | |

| Democratic | Jack May | 8,220 | 43.47% | |

| Total votes | 18,911 | 100.0% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin, III | 17,284 | 65.87% | |

| Republican | Lyman Clark | 8,955 | 34.13% | |

| Total votes | 26,239 | 100.0% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

1988

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin III (incumbent) | 13,932 | 63.58% | |

| Democratic | Anthony J. Yanero | 7,981 | 36.42% | |

| Total votes | 21,913 | 100.0% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin III (incumbent) | 29,792 | 100.00% | |

| Total votes | 29,792 | 100.00% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

1992

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin III (incumbent) | 17,238 | 100.00% | |

| Total votes | 17,238 | 100.00% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin III (incumbent) | 33,218 | 100.00% | |

| Total votes | 33,218 | 100.00% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

1996

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Charlotte Pritt | 130,107 | 39.54% | |

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 107,124 | 32.56% | |

| Democratic | Jim Lees | 64,100 | 19.48% | |

| Democratic | Larrie Bailey | 15,733 | 4.78% | |

| Democratic | Bobbie Edward Myers | 3,038 | 0.92% | |

| Democratic | Lyle Sattes | 2,931 | 0.89% | |

| Democratic | Bob Henry Baber | 1,456 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Louis J. Davis | 1,351 | 0.41% | |

| Democratic | Frank Rochetti | 1,330 | 0.40% | |

| Democratic | Richard E. Koon | 1,154 | 0.35% | |

| Democratic | Fred Schell | 733 | 0.22% | |

| Total votes | 329,057 | 100.00% | ||

2000

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin, III | 141,839 | 51.08% | |

| Democratic | Charlotte Pritt | 80,148 | 28.86% | |

| Democratic | Mike Oliverio | 35,424 | 12.76% | |

| Democratic | Bobby Nelson | 20,259 | 7.30% | |

| Total votes | 277,670 | 100.00% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin, III | 478,489 | 89.44% | |

| Libertarian | Poochie Myers | 56,477 | 10.56% | |

| Total votes | 534,966 | 100.00% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

2004

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 149,362 | 52.73% | |

| Democratic | Lloyd M. Jackson II | 77,052 | 27.20% | |

| Democratic | Jim Lees | 40,161 | 14.18% | |

| Democratic | Lacy Wright, Jr. | 4,963 | 1.75% | |

| Democratic | Jerry Baker | 3,009 | 1.06% | |

| Democratic | James A. Baughman | 2,999 | 1.06% | |

| Democratic | Phillip Frye | 2,892 | 1.02% | |

| Democratic | Lou Davis | 2,824 | 1.00% | |

| Total votes | 283,262 | 100.00% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 472,758 | 63.51% | +13.39% | |

| Republican | Monty Warner | 253,131 | 34.00% | -13.21% | |

| Mountain | Jesse Johnson | 18,430 | 2.48% | +0.87% | |

| Write-in | 114 | 0.02% | +0.01% | ||

| Margin of victory | 219,627 | 29.50% | +26.58% | ||

| Total votes | 744,433 | ||||

| Democratic hold | Swing | ||||

2008

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin (incumbent) | 264,775 | 74.62% | |

| Democratic | Mel Kessler | 90,074 | 25.38% | |

| Total votes | 354,849 | 100.00% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin (incumbent) | 492,697 | 69.81% | +6.30% | |

| Republican | Russ Weeks | 181,612 | 25.73% | -8.27% | |

| Mountain | Jesse Johnson | 31,486 | 4.46% | +1.99% | |

| Margin of victory | 311,085 | 44.08% | +14.57% | ||

| Total votes | 705,795 | 100% | |||

| Democratic hold | Swing | ||||

2010

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 67,498 | 72.9% | |

| Democratic | Ken Hechler | 16,039 | 17.3% | |

| Democratic | Sheirl Fletcher | 9,035 | 9.8% | |

| Total votes | 92,572 | 100.0% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin | 283,358 | 53.47% | -10.96% | |

| Republican | John Raese | 230,013 | 43.40% | +9.69% | |

| Mountain | Jesse Johnson | 10,152 | 1.92% | +0.06% | |

| Constitution | Jeff Becker | 6,425 | 1.21% | N/A | |

| Majority | 53,345 | 10.07% | |||

| Total votes | 529,948 | 100% | |||

| Democratic hold | |||||

2012

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin (incumbent) | 163,891 | 79.9% | |

| Democratic | Sheirl Fletcher | 41,118 | 20.1% | |

| Total votes | 205,009 | 100% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin (incumbent) | 399,908 | 60.57% | +7.10% | |

| Republican | John Raese | 240,787 | 36.47% | -6.93% | |

| Mountain | Bob Henry Baber | 19,517 | 2.96% | +1.04% | |

| Total votes | 660,212 | 100.0% | N/A | ||

| Democratic hold | |||||

2018

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin (incumbent) | 112,658 | 69.86% | |

| Democratic | Paula Jean Swearengin | 48,594 | 30.14% | |

| Total votes | 161,252 | 100% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Manchin (incumbent) | 290,510 | 49.57% | -11.0% | |

| Republican | Patrick Morrisey | 271,113 | 46.26% | +9.79% | |

| Libertarian | Rusty Hollen | 24,411 | 4.17% | N/A | |

| Total votes | 586,034 | 100% | N/A | ||

| Democratic hold | |||||

Notes[]

- ^ Members of the West Virginia House of Delegates are elected from multi-member districts. Since voters can vote for multiple candidates, there is no percentage.

References[]

- ^ "Senator Joseph Manchin (Joe) (D-West Virginia) - Biography from LegiStorm". legistorm.com. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- ^ Nicholson, Jonathan. "A socialist in charge of the budget in the U.S. Senate? No problem, Democratic moderates say". MarketWatch. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foran, Clare (May 9, 2017). "West Virginia's Conservative Democrat Gets a Primary Challenger". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Gonyea, Don (October 24, 2015). "West Virginia Tells The Story Of America's Shifting Political Climate". NPR.

- ^ "Joe Manchin digs in: 'Under no circumstances' would break tie to nuke filibuster and pack court". Washington Examiner. November 11, 2020. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ "'The Democratic version of John McCain'". POLITICO. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sirota, David (March 8, 2021). "Joe Biden might be in the White House, but Joe Manchin runs the presidency". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zhao, Christina (March 7, 2021). "Joe Manchin Insists He Doesn't Like Being Most Powerful Senator as He Appears on 4 Sunday Shows". Newsweek. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Burton, Danielle (August 1, 2008). "10 Things You Didn't Know About West Virginia Gov. Joe Manchin". US News & World Report. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- ^ "Manchin's mom was a tomboy in her youth". The Register-Herald. December 26, 2009. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ Baxter, Anna (August 26, 2008). "Day 2: Democratic National Convention". WSAZ-TV. Archived from the original on August 31, 2008. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ "A Day with Joe Manchin". The Shepherdstown Observer. August 7, 2010. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010.

- ^ "Gov. Joe Manchin (D)". National Journal. June 22, 2005. Archived from the original on January 5, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ Fournier, Eddie (November 2008). "Joe Manchin III". Our States: West Virginia. EBSCO Publishing. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1-4298-1207-8.

- ^ "Manchin, Joe, III, (1947-)". Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ Casagrande, Michael (August 28, 2014). "US Senator vacationed with childhood friend Nick Saban but can't cheer for him Saturday". AL.com. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- ^ Kotch, Alex (July 20, 2021). "The Democrat blocking progressive change is beholden to big oil. Surprised?". The Guardian. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ Quinones, Manuel; Schor, Elana (July 26, 2011). "Sen. Manchin Maintains Lucrative Ties to Family-Owned Coal Company". New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ Moore, David (July 1, 2021). "Manchin Profits From Coal Sales to Utility Lobbying Group Members". Sludge. Retrieved July 23, 2021.