John F. Collins

John F. Collins | |

|---|---|

| |

| 50th Mayor of Boston | |

| In office January 4, 1960[1] – January 1, 1968[2] | |

| Preceded by | John B. Hynes |

| Succeeded by | Kevin H. White |

| Member of the Massachusetts Senate from Suffolk County | |

| In office 1951–1955 | |

| Preceded by | Chester A. Dolan Jr. |

| Succeeded by | James W. Hennigan Jr. |

| Constituency | 5th Suffolk |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives from Suffolk County | |

| In office 1947–1951 | |

| Preceded by | Frederick R. Harvey (11th) Vincent A. Mannering (10th) |

| Succeeded by | George Greene (11th) Louis K. Nathanson (11th) Timothy J. McInerney (10th) Philip Anthony Tracy (10th) David J. O'Connor (10th) |

| Constituency | 11th Suffolk (1947–1949) 10th Suffolk (1949–1951) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Frederick Collins July 20, 1919 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | November 23, 1995 (aged 76) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Resting place | St. Joseph's Cemetery in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Patricia Cunniff

(m. 1946) |

| Alma mater | Suffolk University Law School |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1941-1946 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | Counterintelligence Corps |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

John Frederick Collins (July 20, 1919 – November 23, 1995) was the Mayor of Boston, Massachusetts from January 4, 1960 to January 1, 1968 under whose tenure the Boston Housing Authority actively segregated its public housing developments and whose property tax assessor's office implemented racially discriminatory assessments. In 1963, Collins and Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) executive Edward J. Logue organized a consortium of savings banks, cooperatives, and federal and state savings and loan associations in the city called the Boston Banks Urban Renewal Group (B-BURG) that would reverse redline parts of Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan along Blue Hill Avenue. In April 1965, a special committee appointed by the Massachusetts Education Commissioner found the Boston Public Schools to be racially imbalanced due to housing segregation, leading to the passage of the Racial Imbalance Act signed into law by Massachusetts Governor John Volpe the following August.

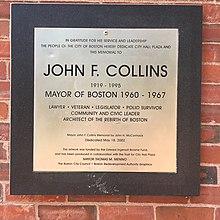

Also in August 1965, Collins publicly requested that the University of Massachusetts Boston not locate its campus permanently in Park Square or elsewhere in Downtown Boston, having the BRA propose locating the campus permanently at the former Columbia Point landfill closed in 1963 instead (and where the school would ultimately move to in 1974). During the long, hot summer of 1967, Collins directed the Boston Police Department response to rioting in Roxbury following a protest at the Grove Hall welfare office. His Associated Press obituary noted that the urban renewal policies Collins implemented in Boston were emulated across the United States. In 2004, nine years after his death, the city government commissioned a mural of Collins on the exterior of Boston City Hall adjacent to Government Center station and dedicated City Hall Plaza to him as well.

Early life[]

John Collins was born in Roxbury on July 20, 1919 to an Irish Catholic family.[3] His father, Frederick "Skeets" Collins, worked as a mechanic for the Boston Elevated Railway.[4] Collins graduated from Roxbury Memorial High School, and in 1941, from Suffolk University Law School.[3] He served a tour in the Army Counterintelligence Corps during World War II, rising in rank from private to captain.[3][5] He was a member of the Knights of Columbus.[6]

In 1946, Collins married Mary Patricia Cunniff, a legal secretary, who Collins had met through his work as an attorney. She would later campaign for Collins when he was incapacitated by polio.[7] The couple had four children.

Early political career[]

In 1947, Collins was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, representing Jamaica Plain, and, in 1950, to the Massachusetts State Senate.[3][5] Collins spent two terms as senator and then ran unsuccessfully for state attorney general in 1954, losing to George Fingold.[3] While campaigning for a seat on the City Council in 1955, Collins and his children contracted polio. Collins' children recovered and he continued with his campaign despite warnings from his doctors.[3] As a result of the disease, Collins was forced to use a wheelchair or crutches for the rest of his life.[8] He was elected to the Council and the following year was appointed Register of Probate for Suffolk County.[3]

Mayor of Boston[]

In 1959, Collins ran against Massachusetts Senate President John E. Powers for Mayor of Boston. Collins was widely viewed as the underdog in the race.[3] Powers was supported by Massachusetts U.S. Senator John F. Kennedy.[9][10] Collins ran on the slogan "stop power politics", and was widely seen as independent of any political machine.[3][5] Collins' victory in the 1959 mayoral election was considered the biggest upset in city politics in decades.[11] Boston University political scientist Murray Levin wrote a book on the race, titled The Alienated Voter: Politics in Boston, which attributed Collins' victory to the voters' cynicism and resentment of the city's political elite.[12]

Collins won re-election in 1963, easily defeating City Councilor Gabriel Piemonte. In 1966, a Boston Globe poll showed deep dissatisfaction with the Collins administration's urban renewal policies.[13] In 1966, Collins ran for the United States Senate seat being vacated by the retiring former Senate Republican Conference Whip Leverett Saltonstall, but lost in the primary to former Massachusetts Governor Endicott Peabody (who in turn would lose to Massachusetts Attorney General Edward Brooke). Despite receiving 42 percent of the vote statewide, Collins lost 21 out of Boston's 22 wards. Weakened politically, Collins declined to seek reelection in 1967 and was succeeded by Massachusetts Secretary of the Commonwealth Kevin White.[14]

Urban renewal[]

Collins inherited a city in fiscal distress. Property taxes in Boston were twice as high as in New York or Chicago, even as the city's tax base was declining. Collins established a close relationship with a group of local business leaders known as the Vault, cut taxes in five of his eight years in office and imposed budget cuts on city government. Collins' administration focused on downtown redevelopment: Collins brought the urban planner Edward J. Logue (who had been serving as the administrator of the New Haven Redevelopment Agency) to Boston to lead the Boston Redevelopment Authority and Collins' administration supervised the construction of the Prudential Center complex and of Government Center.[11][14][15]

When Collins lost his campaign for Massachusetts Attorney General in 1954, only one new private office building had appeared on the city skyline since 1929.[16] One in five of the city's housing units were classified as dilapidated or deteriorating and the city was ranked lowest among major cities in building starts, while the only growing industries in the city were government and universities (leading to a narrowing tax base) and the city already had a higher number of municipal employees per capita than any major city in the United States.[17] Urban renewal would affect 3,223 acres of the city, be highly profitable for the city's business community, and by the 1970s, led to Boston having the fourth-largest central-business-district office space in the United States as well as the highest construction rates.[13] However, the city would lose more dwelling units than it would gain during the 1960s as Collins' budget priorities led to a decrease in city services outside of downtown, particularly parks, playgrounds, and schools in residential neighborhoods, and would often displace poor blacks and whites into neighborhoods with higher rents.[18]

In March 1965, an investigative study of property tax assessment practices published by the National Tax Association of 13,769 properties sold within the City of Boston from January 1, 1960 to March 31, 1964 found that the assessed values in the neighborhood of Roxbury in 1962 were at 68 percent of market values while the assessed values in West Roxbury were at 41 percent of market values, and the researchers could not find a nonracial explanation for the difference.[19][20] In 1963, the city government broke ground on a new city hall and surrounding plaza in Scollay Square.[13] In the same year, Collins and Edward Logue organized a consortium of savings banks, cooperatives, and federal and state savings and loan associations in the city called the Boston Banks Urban Renewal Group (B-BURG) that would provide $2.5 million in Federal Housing Administration (FHA) insured rehabilitation and home-ownership loans at less than 5.25% interest in Washington Park around Dudley Square in Roxbury.[21]

In the mid-1960s, Carl Ericson, Vice President of the Suffolk Franklin Savings Bank (a B-BURG member institution), began making loans to white professionals in the South End, causing displacement of the decades-old local black population into North Dorchester.[22][18] In 1964, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized 21 black families in the city's first rent strike,[23] and in 1965, CORE distributed a list of property owners in the city in violation of state and city building codes.[24] In the summer of 1967, FHA Executive Assistant Commissioner Edwin G. Callahan conducted a suitability tour for a 2,000-unit housing rehabilitation program in Roxbury called the Boston Rehabilitation Program (BURP).[25] At a press conference at Freedom House in Roxbury on December 3, 1967, U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Robert C. Weaver announced the $24.5 million program.[26]

Public housing[]

In May 1962, Boston NAACP President Melnea Cass filed a formal complaint with the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination alleging a pattern of discrimination in public housing in the city, citing that the Mission Hill Extension project went from 314 nonwhite families in 1957 to 492 nonwhite families of 572 units in 1961 while the Mission Hill project remained all-white.[27] In the same year, upon receipt of a lawsuit filed by a civil rights group, the West Broadway Housing Development was desegregated after having been designated by the city for white-only occupancy since 1941.[28] Despite the passage of legislation in 1950 by the 156th Massachusetts General Court prohibiting racial discrimination or segregation in housing, under Public Housing Administration regulations, a public housing authority could designate projects as integrated even if it contained only one nonwhite person.[29]

In September 1962, 17 of the 25 public housing developments for families and all 5 elderly-only developments were collectively 99 percent white, while 4 of the 8 remaining family developments were 93 percent nonwhite and the other 4 located in Roxbury, the South End, Jamaica Plain, and Columbia Point were becoming increasingly nonwhite.[30] When the Columbia Point development first opened in 1953, white tenants made up more than 90 percent of the population while black families made up approximately 7 percent,[31] but by the early 1960s, white families started refusing assignment there and the Boston Housing Authority (BHA) reserved developments in South Boston for them instead, while moving black families to Columbia Point.[32] Also in September 1962, the city's federally-funded developments were highly segregated, and of the 3,686 state-funded units, only 129 were occupied by whites and two-thirds of nonwhites in state-sponsored units were living in an all-black development adjacent to the all-black Lenox Street Projects.[30]

On November 20, 1962, President Kennedy issued Executive Order 11063 requiring all federal agencies to prevent racial discrimination in federally-funded subsidized housing in the United States.[29] On February 28, 1963, Collins met with President Kennedy at the White House.[33] In May 1963, Collins appointed Ellis Ash, Edward Logue's deputy at the Boston Redevelopment Authority, to be the acting Administrator of the BHA,[34] and Ash later noted that though Collins believed that integration was inevitable, he was opposed to it.[35] In 1964, all 852 Old Colony Housing Project units had white tenants, only 1 of the 1,010 Mission Hill units had a nonwhite tenant, while the Mission Hill Extension project had 509 nonwhite tenants of 580 units, and 220 of the 1,392 Columbia Point units had nonwhite tenants (or approximately 16 percent).[36]

In 1967, the city government agreed to fully desegregate the Mission Hill and Mission Hill Extension developments, which were still 97 percent white and 98 percent black respectively,[28] while 8 projects in the city as a whole remained more than 95 percent white and 5 others remained 90 percent white and nonwhites made up the majority of the waiting list.[37] Despite Ellis Ash's appointment, the BHA Board Chair retained effective control over tenant assignment until 1968,[38] and like Collins, BHA Board Chair Edward Hassan (1960–1965) also opposed integration.[39][40] Ash would continue to receive bureaucratic resistance against integration from the Board and BHA departments through at least 1966,[38] as well as from state officials when attempting to desegregate the state's Chapter 200 public housing program in 1964.[41]

Also in 1963, the Congress of Racial Equality requested comments from the BHA Board with allegations of discrimination by family composition and source of income in rejecting applications from mothers with illegitimate children or who were receiving Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) payments.[39] The non-marital birthrate among whites and nonwhites nationally rose from 2 percent and 17 percent respectively in 1940 (5 years after ADC was created under the Social Security Act signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935) to 4 percent and 26 percent respectively when the Moynihan Report was published in March 1965.[42][43][44]

In November 1965, under new BHA Chair Jacob Brier, the BHA adopted new Occupancy Standards to replace a set of 15 exclusionary criteria while continuing to allow the Board to screen tenants using the previous criteria.[45] Screened applications were referred to a Tenant and Community Relations Department staffed by social workers, and while the majority of the referrals remained for out-of-wedlock births, of the first 297 referrals the new department received only 14 (less than 5 percent) were denied.[46] On April 11, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1968 including Titles VIII and IX introduced by Massachusetts U.S. Senator Edward Brooke prohibiting discrimination in the sale or rental of housing.[47]

UMass Boston and Boston Public Schools[]

On June 18, 1964, Massachusetts Governor Endicott Peabody signed into law the bill establishing the University of Massachusetts Boston,[48] and in September 1965, undergraduate courses began at the former headquarters of the Boston Gas Company in Park Square.[49] In August 1965, Collins publicly requested that UMass Boston Chancellor John W. Ryan not consider a permanent campus at its current site in Park Square or elsewhere in Downtown Boston (as a disproportionate amount of the real estate there was already owned by many colleges and other non-profit institutions exempt from the city government's property taxes), and to move to a suburban campus or one located in an underdeveloped section of Roxbury instead, while University of Massachusetts President John W. Lederle insisted on a campus inside the city limits.[50] In May 1966, following organized opposition from residents, Collins spoke with Chancellor Ryan and a proposal to locate the UMass Boston campus near Highland Park was cancelled.[51] In 1967, the Boston Redevelopment Authority proposed locating the campus permanently at the former Columbia Point landfill closed in 1963.[52][53][54] In response, in November 1967, 1,500 faculty and students organized a rally on Boston Common demanding a location in Copley Square.[55]

On April 1, 1965, a special committee appointed by Massachusetts Education Commissioner Owen Kiernan released its final report finding that more than half of black students enrolled in Boston Public Schools (BPS) attended institutions with enrollments that were at least 80 percent black and that housing segregation in the city had caused the racial imbalance.[56][57][58] From its creation under the National Housing Act of 1934 signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Federal Housing Administration used its official mortgage insurance underwriting policy explicitly to prevent school desegregation.[59] In response, on April 20, the Boston NAACP filed a lawsuit in federal district court against the city seeking the desegregation of the city's public schools.[60] Massachusetts Governor John Volpe filed a request for legislation from the state legislature that defined schools with nonwhite enrollments greater than 50 percent to be imbalanced and granted the State Board of Education the power to withhold state funds from any school district in the state that was found to have racial imbalance, which Volpe would sign into law the following August.[57][61][62]

Also in August 1965, along with Governor Volpe and BPS Superintendent William Ohrenberger, Collins opposed and warned the Boston School Committee that a vote that they held that month to abandon a proposal to bus several hundred blacks students from Roxbury and North Dorchester from three overcrowded schools to nearby schools in Dorchester and Brighton, and purchase an abandoned Hebrew school in Dorchester to relieve the overcrowding instead, could now be held by a court to be deliberate acts of segregation.[63] Pursuant to the Racial Imbalance Act, the state conducted a racial census and found 55 imbalanced schools in the state with 46 in Boston, and in October 1965, the State Board required the School Committee to submit a desegregation plan, which the School Committee did the following December.[64]

In April 1966, the State Board found the plan inadequate and voted to rescind state aid to the district, and in response, the School Committee filed a lawsuit against the State Board challenging both the decision and the constitutionality of the Racial Imbalance Act the following August. In January 1967, Massachusetts Superior Court overturned a Suffolk Superior Court ruling that the State Board had improperly withdrawn the funds and ordered the School Committee to submit an acceptable plan to the State Board within 90 days or else permanently lose funding, which the School Committee did shortly thereafter and the State Board accepted. In June 1967, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court upheld the constitutionality of the Racial Imbalance Act and the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren (1953–1969) declined to hear the School Committee's appeal in January 1968.[65]

Grove Hall riots and race relations[]

In April 1962, Collins' administrative staff described protests in Columbia Point following a six-year old girl being run over and killed by a dump truck operated by a negligent city government employee as "interracial riots."[66] In response to the Boston NAACP complaint in May 1962 to Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination, the Boston Housing Authority rented a single apartment to an elderly black woman in the Mission Hill development which was stoned over two consecutive nights,[67] and Collins aides scuttled a formal probe of the incident by the Massachusetts Attorney General's office.[66] Amidst growing urban race rioting in the United States, in December 1965, the American Sociological Review published a survey conducted by sociologists Stanley Lieberson and Arnold R. Silverman of 76 black-white race riots in the United States from 1913 to 1963 and found that riots were more common in cities with smaller percentages of blacks who were store owners, smaller proportions of blacks on the city police force relative to the local black population, and where the population per city councilor was larger or where city councilors were elected at-large rather than by ward.[68]

In 1949, an amendment to the city charter reduced membership on the Boston City Council from 22 seats elected by ward down to 9 seats elected by citywide at-large elections, and in 1951, the only African American sitting on the City Council, Laurence H. Banks of Roxbury (a former member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives) lost re-election,[69][70] and no African Americans would serve on the City Council until the election of Thomas Atkins in 1967.[71] From 1960 to 1970, the ratio of Boston's population that was black grew from 9 percent to 16 percent, as part of the second wave of the African-American Great Migration (1916–1970), while the total population of the city declined from approximately 697,000 to 641,000.[72][73] As late as 1970, less than 3 percent of Boston Police Department officers were black,[74] and 70 percent of black men in the city were employed as manual workers in comparison to slightly less than half of white men, and as in 1950, black men earned only three-quarters of what their white counterparts did.[75]

On April 23, 1965, after leading a march from Roxbury to Boston Common and giving speeches at both locations, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. met with Collins in an informal after-hours meeting along with Rev. Ralph Abernathy and Rev. Virgil Wood (the regional representative of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and former pastor at the Diamond Hill Baptist Church in Lynchburg, Virginia).[76][77] On May 22, 1966, Collins declared the 142nd day of the year as "Melnea Cass Day" in the city in honor of Boston NAACP President Melnea Cass.[78] On April 26, 1965, the recently formed Mothers for Adequate Welfare (MAW) organized a sit-in at the Welfare Department Office on Hawkins Street,[74] marched on the Massachusetts State House in July 1966 and organized a subsequent sit-in at a welfare office on Blue Hill Avenue on May 26, 1967. On Friday, June 2, during a summer when 159 race riots occurred across the United States, 25 white and black MAW members and a contingent of college students arrived at the Grove Hall welfare office at 4:20 PM, presented a list of 10 demands, and chained the doors from the inside, preventing 58 office employees from leaving.[79] At 4:45 PM, fire and police arrived while a crowd grew outside, and upon receiving a call that an office worker was having heart trouble, Collins ordered the police to enter by any means possible, remove the workers, and arrest the protestors.[80]

By 5:30 PM, police had entered the rear of the facility, and a woman appeared at a window screaming that the police were beating people inside.[81] By 8:10 PM, the police had emptied the building, while the crowd had begun throwing projectiles at the police and then migrated from Grove Hall across nearly 15 blocks of Blue Hill Avenue.[82][80] By 9:30 PM, 30 people had been seriously injured and more than $500,000 in property damage had been committed.[83] By 4:30 AM, arsonists had destroyed two buildings (with damage estimated at $50,000), police had made 44 arrests, and the injured numbered 45.[84] The following morning, Saturday, June 3, MAW stated that a deputy superintendent said, "get them, beat them, use clubs if you have to, but get them out of here," with one mother described being "beaten, kicked, dragged, abused, insulted and brutalized" by police who used "vulgar language" and repeated the word "nigger," while Deputy Superintendent William A. Bradley stated, "The demonstrators refused to move. … As officers tried to break in, they were kicked, beaten, thrown to the floor and cut with glass."[82]

Collins called the demonstration, "the worst manifestation of disrespect for the rights of others that this city has ever seen."[81] Collins ordered the Boston Police Department to close all bars and liquor stores on Blue Hill Avenue, but by 10:30 PM, fire alarms were being falsely set off, and unplanned spontaneous outbursts of violence occurred among roving gangs in Roxbury through the night.[84] On the evening of Sunday, June 4, 1,900 police were called in to quell further rioting and looting in the Grove Hall area, making 11 arrests, and with 11 more being injured. On Monday, June 5, violence began subsiding with only sporadic outbursts, and on Tuesday, June 6, 60 fire alarms were falsely set off while no violence occurred. Collins and the Boston Police Department attributed the violence to a criminal element among the rioters rather than racial conditions in the city.[85]

Retirement and legacy[]

After leaving office in 1968, Collins held visiting and consulting professorships at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for 13 years.[86] In the early 1970s, Collins drifted away from the Democratic Party. He chaired the group Massachusetts Democrats and Independents for Nixon and, in 1972, attacked Democrats for "their crazy policies of social engineering and abortion."[8] Collins was considered for the position of Secretary of Commerce in the Nixon administration.[5]

Redlining and busing[]

In 1968, the Boston Banks Urban Renewal Group (B-BURG) consisted of 22 institutions that collectively held $4 billion in assets or 90 percent of the region's thrift industry.[21] On March 20, 1968, a $996,000 FHA commitment was made through the Boston Rehabilitation Program (BURP) to the Sanders Associates (a housing development group created by Boston Celtics forward Tom Sanders in response to a search led by local energy business executive Eli Goldston) for the rehabilitation of 83 units in Roxbury after local community activists (including Mel King) criticized BURP for a lack of sufficient community control and racial equity.[87] On May 13, Boston Mayor Kevin White announced a $50 million loan commitment program with B-BURG.[22] On July 31, B-BURG opened a headquarters on Warren Street near Dudley Square.[88] In July and August, B-BURG executives held meetings to define the geographic scope of a $29 million loan program within a Model Cities area, with Suffolk Franklin Vice President Carl Ericson proposing areas of Mattapan and Roxbury along Blue Hill Avenue.[22][89][90]

Over the summer and fall of 1968, real estate advertising by mail and telephone using blockbusting tactics began to be circulated in Mattapan.[91] According to a Model Cities study, 65 percent of the houses purchased under the B-BURG program from 1968 to 1970 needed major repairs at the time of purchase, and a later 1971 survey found that 65 percent of the houses sold under the B-BURG program needed major repairs within two years of purchase, and Joseph Kenealy, head appraiser for the FHA in Boston, received a lawsuit in 1971 from the U.S. Justice Department alleging that he used the office to enrich himself and family members by $350,000.[92] By March 31, 1970, more than 1,300 minority families bought homes with B-BURG mortgages with the vast majority being steered into the Jewish neighborhoods of Mattapan (where the black population increased from 473 in 1960 to 19,107 in 1970), while approximately 15,000 people in total found new residences during the first 20 months of the program.[93] With the first immigrants arriving in the 1920s, Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan would become home to a population of as many as 90,000 Jews.[94] By 1957, 40,000 Jews remained in Dorchester alone with an additional 10,000 Jews in Mattapan,[95] but within the two years from 1968 to 1970, more than five decades of Jewish settlement would be overturned by its inclusion in the B-BURG loan area by Suffolk Franklin Vice President Carl Ericson.[94][89]

In March 1969, Boston City Councilor Thomas Atkins met with Robert Morgan, President of the Boston Five Cents Savings Bank (a B-BURG member institution), about the B-BURG loan area.[96] From its creation under the National Housing Act of 1934, official Federal Housing Administration property appraisal underwriting standards to qualify for mortgage insurance had a whites-only requirement excluding all racially mixed neighborhoods or white neighborhoods in proximity to black neighborhoods,[17][59] and this produced a self-fulfilling effect on property values within redlined areas.[97][98] However, instead of denying mortgages to minority homebuyers in white neighborhoods, B-BURG would only approve mortgages within specific neighborhoods of Roxbury and Mattapan causing an artificial restriction to the housing supply available for loanable funds to minorities and increasing the interest rates of the B-BURG loan pool from a range of 4.5 to 5.0% up to 8.5%.[94][99] Within blockbusted neighborhoods, many minority homebuyers ended up in default as a consequence of making mortgage payments far in excess of a property's worth, and in 1968, the FHA announced that it would begin guaranteeing loans in the inner city, reducing a market disincentive against lending in blockbusted neighborhoods.[100]

On May 25, 1971, the Massachusetts State Board of Education voted unanimously to withhold state aid from the Boston Public Schools due to the School Committee's refusal to use the district's open enrollment policy to relieve the city's racial imbalance in enrollments, instead routinely granting white students transfers while doing nothing to assist black students attempting to transfer.[63][101] From September 13 through September 16, the U.S. Senate Judiciary Antitrust and Monopoly Subcommittee chaired by Michigan U.S. Senator Philip Hart held hearings at the John F. Kennedy Federal Building in Boston that established the location and creation of the B-BURG loan area following a written statement from Boston Redevelopment Authority executive Hale Champion and testimony from B-BURG member institution executives and a BRA executive staff member.[102] On the final day of the hearings, a statement received from the office of Boston Mayor Kevin White praised the B-BURG institutions for their rehabilitation and home ownership expansion efforts, but established that White's office was not involved in the drawing of the loan area.[103]

On March 15, 1972, the Boston NAACP filed a lawsuit, later named Morgan v. Hennigan, against the Boston School Committee in federal district court.[104] On June 21, 1974, Judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr. ruled that the open enrollment and controlled transfer policies that the School Committee created in 1961 and 1971 respectively were being used to effectively discriminate on the basis of race, and that the School Committee had maintained segregation in the Boston Public Schools by adding portable classrooms to overcrowded white schools instead of assigning white students to nearby underutilized black schools, while simultaneously purchasing closed white schools and busing black students past open white schools with vacant seats.[105] In accordance with the Racial Imbalance Act, the School Committee would be required to bus 17,000 to 18,000 students the following September (Phase I) and to formulate a desegregation plan for the 1975–1976 school year by December 16 (Phase II).[106][107]

On September 12, 1974, 79 of 80 schools were successfully bused (with South Boston High School being the lone exception),[108] and through October 10, there were 149 arrests (40 percent occurring at South Boston High alone), 129 injuries, and $50,000 in property damage.[109][110] On October 15, an interracial stabbing at Hyde Park High School led to a riot that injured 8, and at South Boston High on December 11, a non-fatal interracial stabbing led to a riotous crowd of 1,800 to 2,500 whites hurling projectiles at police while white students fled the facility and black students remained.[111] State Senator William Bulger, State Representative Raymond Flynn, and Boston City Councilor Louise Day Hicks made their way to the school, and Hicks spoke through a bullhorn to the crowd and urged them to allow the black students still in South Boston High to leave in peace, which they did, while the police made only 3 arrests, the injured numbered 25 (including 14 police), and the rioters badly damaged 6 police vehicles.[112]

Twenty minutes after Judge Garrity's deadline for submitting the Phase II plan expired on December 16, the School Committee voted to reject the desegregation plan proposed by the department's Educational Planning Center.[107] On December 18, Garrity summoned all five Boston School Committee members to court, held three of the members to be in contempt of court on December 27, and told the members on December 30 that he would purge their contempt holdings if they voted to authorize submission of a Phase II plan by January 7.[113] On January 7, 1975, the School Committee directed school department planners to file a voluntary-only busing proposal with the court.[114] On February 12, interracial fighting broke out at Hyde Park High that would last for three days with police making 14 arrests, while no major disturbances occurred in March or April.[115]

On May 3, 1975, the Progressive Labor Party (PLP) organized an anti-racism march in South Boston, where 250 PLP marchers attacked 20 to 30 South Boston youths and over 1,000 South Boston residents responded, with the police making 8 arrests (including 3 people from New York City) and the injured numbered 10.[115] On May 10, the Massachusetts U.S. District Court announced a Phase II plan requiring 24,000 students to be bused that was formulated by a four-member committee consisting of former Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Justice Jacob Spiegel, former U.S. Education Commissioner Francis Keppel, Harvard Graduate School of Education professor Charles V. Willie, and former Massachusetts Attorney General Edward J. McCormack that was formed by Judge Garrity the previous February.[116] From June 10 through July 7, police made no arrests in more than a dozen of what they described as "racial incidents."[117]

On July 27, 1975, a group of black bible salesmen from South Carolina went swimming on Carson Beach, and in response, hundreds of white male and female bathers gathered with pipes and sticks and chased the bible salesmen from the beach on foot with the mob destroying their car and the police making two arrests. The following Sunday, August 3, a taxicab with a black driver and three Hispanic passengers were subjected to projectiles from passerby as they drove past the beach. In response, on August 10, black community leaders organized a protest march and picnic at the beach where 800 police and a crowd of whites from South Boston were on hand. 2,000 blacks and 4,000 whites fought and lobbed projectiles at each other for over 2 hours until police closed the beach after 40 injuries and 10 arrests.[118]

On September 8, 1975, the first day of school, while there was only one school bus stoning from Roxbury to South Boston, citywide attendance was only 58.6 percent, and in Charlestown (where only 314 of 883 students or 35.6 percent attended Charlestown High School) gangs of youths roamed the streets hurling projectiles at police, overturning cars, setting trash cans on fire, and stoning firemen. 75 youths stormed Bunker Hill Community College after classes ended and assaulted a black student in the lobby, while 300 youths marched up Breed's Hill, overturning and burning cars. On October 24, 15 students at South Boston High were arrested. On December 9, Judge Garrity ruled that instead of closing South Boston High at the request of the plaintiffs in Morgan v. Hennigan, the school would be put into federal receivership.[119]

On January 21, 1976, 1,300 black and white students fought each other at Hyde Park High, and at South Boston High on February 15, anti-busing activists organized marches under a parade permit from the Andrew Square and Broadway MBTA Red Line stations which would meet and end at South Boston High. After confusion between the marchers and the police about the parade route led marchers to attempt to walk through a police line, the marchers began throwing projectiles at the police, the marchers regrouped, and migrated to South Boston High where approximately 1,000 demonstrators engaged with police in a full riot that required the police to employ tear gas. 80 police were injured and 13 rioters were arrested.[120] On April 5, civil rights attorney Ted Landsmark was stabbed by a white teenager at City Hall Plaza with a flagpole bearing the American flag (famously depicted in a 1977 Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph, The Soiling of Old Glory published in the Boston Herald American by photojournalist Stanley Forman).[121]

On April 19, 1976, black youths in Roxbury assaulted a white motorist and beat him comatose, while numerous car stonings occurred through April, and on April 28, a bomb threat at Hyde Park High emptied the building and resulted in a melee between black and white students that require police action to end.[122] On June 14, the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice Warren E. Burger (1969–1986) unanimously declined to review the School Committee's appeal of the Phase II plan.[123] On the evening of September 7, the night before the first day of school, white youths in Charlestown threw projectiles at police and injured 2 U.S. Marshals, a crowd in South Boston stoned an MBTA bus with a black driver, and the next day, youths in Hyde Park, Roxbury, and Dorchester stoned buses transporting outside students in.[124] From September 1974 through the fall of 1976, at least 40 riots had occurred in the city.[125] From July 1977 through June 1978, 91 percent of the government-insured foreclosures in Boston were in Dorchester, Mattapan, and Roxbury, with 53 percent of the city's foreclosures in South Dorchester and Mattapan alone, and 84 percent of the 93 foreclosures in Dorchester were concentrated in the B-BURG program census tracts.[99]

Despite the passage of the Community Reinvestment Act in 1977 banning redlining, the legislation was not seriously enforced by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in the 1980s during the Reagan Administration while the Department itself was rife with corruption.[126][127] By the early 1990s, the overwhelming majority of Boston's 120,000 black residents lived in Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan.[94] In December 1982, Judge Garrity transferred responsibility for monitoring of compliance to the State Board for the subsequent two years, and in September 1985, Judge Garrity issued his final orders returning jurisdiction of the schools to the School Committee.[128] In May 1990, Judge Garrity delivered his final judgment in Morgan v. Hennigan, formally closing the original case.[129] On January 2, 1991, the NAACP and HUD came to a settlement in a 12-year lawsuit that $450 million would be made available to minority homebuyers in Greater Boston over the next 15 years.[130] Incidents of interracial violence in Boston would continue from November 1977 through at least 1993.[131]

UMass Boston and Columbia Point[]

In February 1968, UMass Boston Chancellor John W. Ryan proposed a 15-acre campus over the Massachusetts Turnpike and south of where the proposed John Hancock Tower was to be built which the Boston Redevelopment Authority rejected.[55] In October 1968, 2,500 UMass Boston faculty and students rallied in front of the Massachusetts State House still demanding a Copley Square or Park Square location.[132] Following his appointment as UMass Boston Chancellor in August of the same year,[133] Francis L. Broderick proposed a scattered site campus in the South End along the MBTA Green Line in November 1968.[134][132] After reviewing Broderick's proposal, the UMass Board of Trustees voted 12 to 4 to accept the Columbia Point campus proposal from the BRA in December 1968.[135]

In April 1969, the Students for a Democratic Society rallied more than a hundred students protesting the decision to move the university campus to Columbia Point, denouncing the institution as "a 'pawn' masking the Boston Redevelopment Authority's plan to remove poor people from Columbia Point" and that "the university is planning a prestigious dormitory school with high tuition which students from low- and moderate-income families–whom the university was designed to serve–will not be able to attend."[136] In 1969, the Dorchester Tenants Action Council (DTAC) formed to prevent an influx of students into the public housing project on Mount Vernon Street,[137] while a bill proposed in the Massachusetts House of Representatives to construct dormitories failed to pass.[138]

In January 1974, the university moved to the current Columbia Point campus.[139] In the same year, only 75 percent of the units in the Columbia Point public housing project were occupied, and the Boston Housing Authority now thought of the complex as "housing of last resort."[32] In 1977, the 170th Massachusetts General Court formed a special legislative committee led by Amherst College President John William Ward that found that the Columbia Point campus was negligently constructed (in addition to extortion payments made to Massachusetts Senate Majority Leader Joseph DiCarlo and State Senator Ronald MacKenzie by McKee-Berger-Mansueto, the company contracted to supervise the construction of the campus).[140][141][142]

By the 1980s, only 300 families were living in the Columbia Point housing development, in part, because the BHA had allowed the buildings to deteriorate and be occupied by squatters, and the public housing project had drawn comparisons to the Pruitt–Igoe Apartments in St. Louis and the Cabrini–Green Homes in Chicago. The city government leased the development on a 99-year contract to a private developer composed of a tenant-run community task force and the Corcoran-Mullins-Jennison Corporation, and in 1986, construction began for the new Harbor Point Apartments complex to replace the original Columbia Point public housing project that was completed in 1990.[143] The housing development is now billed as luxury apartments.[144]

In the 1990s, chunks of concrete began falling from the ceiling of the UMass Boston parking garage underneath the campus substructure due to the saltwater atmosphere, and after 600 spaces had already been lost due to ongoing repairs and rerouting of passenger and vehicular traffic, in July 2006, UMass Boston Chancellor Michael F. Collins ordered the immediate and permanent closure of the garage, causing a loss of 1,500 parking spaces in total.[145][146] In December 2007, UMass Boston Chancellor J. Keith Motley proposed a 25-year master plan to renew the campus that was approved by the UMass System Board of Trustees.[147] In April 2017, Chancellor Motley resigned amidst a $30 million operating budget deficit caused by the construction costs of the renewal plan that required the university to cut courses required for graduation during the upcoming summer and fall semesters as well as other academic spending and layoff 36 university employees.[148][149][150][151]

In May 2019, the Pioneer Institute released a white paper reviewing records obtained from the UMass System Controller's Office (as well as other publicly available documents) that concluded that Chancellor Motley and other UMass Boston administrators were scapegoated for the 2017 fiscal year $30 million budget deficit when UMass System President Marty Meehan commissioned an audit of UMass Boston administration and finances by KPMG for presentation to the UMass System Board of Trustees in November 2017.[152] Instead, the white paper concluded that the approval by the UMass System Board of Trustees of an accelerated 5-year capital spending plan in December 2014 without assuring that capital reserves would be made available to pay for the plan, as well as an error to a 5-year campus reserve ratio estimate prepared by the UMass Central Budget Office and presented to the System Board of Trustees in April 2016, was the cause of the $26 million in budget reductions made at the direction of the UMass Central Office and implemented by interim Chancellor Barry Mills. Additionally, the white paper noted that the acquisition of the Mount Ida College campus by the University of Massachusetts Amherst in April 2018 was conducted by a wire transfer from the UMass System for $75 million at the time the UMass Central Office ordered the budget reductions rather than UMass Amherst purchasing the Mount Ida campus with loanable funds to be repaid with interest (and in contrast to how the transaction was described in a press statement issued by System President Marty Meehan's office).[153][154][155][156]

In 1963, when UMass System President John W. Lederle endorsed expanding the system to Boston before the state legislature, there were 12,000 freshman applications to the University of Massachusetts in Amherst with only 2,600 slots, yet the majority of the applicants lived in the Greater Boston area.[48] In the late 1960s, UMass Boston reportedly had the largest population of Vietnam War veterans of any university in the United States (many of whom had been recently discharged), and the largest population of African American students of all universities in Massachusetts.[157] As of April 2018, the UMass Boston campus was the sole majority-minority campus in the UMass system,[158] and during the 2018–2019 academic year, UMass Boston served 650 military veterans, managed $4 million in federal G.I. benefits, and was ranked by multiple publications as being among the best universities in the United States for veteran students.[159]

Death and burial[]

Collins died of pneumonia in Boston, on November 23, 1995. Five days later, he was buried at St. Joseph Cemetery in West Roxbury following a funeral Mass at Boston's Holy Cross Cathedral celebrated by Cardinal Bernard Francis Law, Archbishop of Catholic Archdiocese of Boston (1984–2002).[160] Obituaries of him published in MIT Tech Talk and by the Associated Press, as well as his entry in The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America (1999) published by the University of Notre Dame Press and written by a member of the Society of Jesus, do not mention that the Boston Housing Authority actively segregated the public housing developments in the city during his tenure, that his property tax assessor's office implemented racially discriminatory assessments, the Boston Police Department response to the Grove Hall riots, or that the Boston Banks Urban Renewal Group redlined Blue Hill Avenue, but the Associated Press obituary noted that the urban renewal policies Collins implemented in Boston were emulated across the United States.[86][161][162][9] In 2004, the same year Illinois State Senator Barack Obama gave the keynote address at the Democratic National Convention in Boston, the city government commissioned a mural of Collins on the exterior of Boston City Hall adjacent to Government Center station and dedicated City Hall Plaza to him as well.[163] The caption engraved in the mural's marker does not mention the segregationist and racially discriminatory housing policies of the Collins mayoral administration or the Grove Hall riots either.

See also[]

- Timeline of Boston, 1960s

References[]

- ^ "Collins Will Take Oath Today". The Boston Globe. January 4, 1960. p. 1. Retrieved March 17, 2018 – via pqarchiver.com.

- ^ "'New Inaugural' in Traditional Boston Setting Today". The Boston Globe. January 1, 1968. p. 3. Retrieved March 17, 2018 – via pqarchiver.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i O'Connor, T.H. (1997). Boston Irish: A Political History. New York: Back Bay Books.

- ^ O'Connor, Thomas H. (1995). Building a New Boston: Politics and Urban Renewal, 1950-1970. Boston: Northeastern Univ Press. p. 152. ISBN 1555532462.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Nolan, Martin (24 November 1995). "Ex-Mayor Collins dead at 76 Fought to restore city's pride, image". The Boston Globe. p. 1.

- ^ Lapomarda, S.J., Vincent A. (1992). The Knights of Columbus in Massachusetts (second ed.). Norwood, Massachusetts: Knights of Columbus Massachusetts State Council. p. 88.

- ^ Girard, Christopher (7 November 2010). "Mary P. Cunniff Collins, 90, provided support to husband as Boston mayor". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Milne, John (29 November 1995). "Collins recalled as a builder". Boston Globe. p. 29.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lapomarda, S.J., Vincent A. (1999). "Boston, Twelve Irish-American Mayors of". In Glazier, Michael (ed.). The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0268027551.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lupo, Alan (3 December 1995). "The Collins legacy: A changed Boston". The Boston Globe. p. 12.

- ^ Tinder, Glenn (January 1961). "Reviews". The Review of Politics. 23 (1): 100. doi:10.1017/s0034670500007774.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lukas, J. Anthony (1986). Common Ground: A Turbulent Decade in the Lives of Three American Families (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 200–201. ISBN 0394746163.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 68–72. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Oldman, Oliver; Aaron, Henry (1965). "Assessment-Sales Ratios Under the Boston Property Tax". National Tax Journal. National Tax Association. 18 (1): 36–49. doi:10.1086/NTJ41791421. JSTOR 41791421. S2CID 232213907.

- ^ Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-1631494536.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 167–168. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 171–173. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 114–116. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 118–120. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 303. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1631494536.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 301–302. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ "Visit of John F. Collins, Mayor of Boston, Massachusetts, 4:00PM – JFK Library". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- ^ Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 308. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 312. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 321. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 319–320. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 295–296. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Grove, Robert D.; Hetzel, Alice M. (1968). Vital Statistics Rates in the United States 1940-1960 (PDF) (Report). Public Health Service Publication. 1677. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, U.S. Public Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics. p. 185.

- ^ Ventura, Stephanie J.; Bachrach, Christine A. (October 18, 2000). Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States, 1940-99 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. 48. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. pp. 28–31.

- ^ The Negro Family: The Case for National Action (Report). Office of Policy Planning and Research, U.S. Department of Labor. 1965. Retrieved March 26, 2021.

- ^ Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 314. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Nelson, Garrison (2017). John William McCormack: A Political Biography. New York: Bloomsbury. p. 724. ISBN 978-1628925166.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 18–21. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Campus by the Sea :: UMass Boston Historic Documents, University of Massachusetts Boston, retrieved August 5, 2017

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Because It Is Right Educationally (Report). Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. 1965. p. viii. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 212–213. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. pp. 64–67. ISBN 978-1631494536.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ "The Racial Imbalance Act of 1965". University of Massachusetts Boston. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Vale, Lawrence J. (2000). From the Puritans to the Projects: Public Housing and Public Neighbors. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 303. ISBN 978-0674025752.

- ^ Lieberson, Stanley; Silverman, Arnold R. (1965). "The Precipitants and Underlying Conditions of Race Riots". American Sociological Review. American Sociological Association. 30 (6): 887–898. doi:10.2307/2090967. JSTOR 2090967. PMID 5846309.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ U.S. Censuses of Population and Housing: 1960 Final Report PHC(1)–18 (PDF) (Report). U.S. Census Bureau. p. 14. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ 1970 Census of Population and Housing: Census Tracts Boston, Mass. Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area PHC(1)–29 (PDF) (Report). U.S. Census Bureau. p. P-1. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Thernstrom, Stephan (1973). The Other Bostonians: Poverty and Progress in the American Metropolis, 1880–1970. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0674433946.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Paiste, Rachel (May 22, 2018). "On 'Melnea Cass Day,' Remembering The Boston Civil Rights Activist And Her Legacy In Roxbury". WBUR. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "John F. Collins, former mayor and MIT professor, dies at 76". MIT Tech Talk. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 29 November 1995. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 175–180. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 208–209. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 271–272. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-1631494536.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 278–299. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 66–69. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. pp. 198–199. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. pp. 204–205. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 75–80. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. pp. 205–206. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. pp. 206–207. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. pp. 211–212. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 98–101. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. pp. 212–213. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. pp. 213–214. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. pp. 215–216. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Oelsner, Lesley (June 15, 1976). "Court Lets Stand Integration Plan In Boston Schools". The New York Times. Retrieved May 6, 2021.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 305. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. pp. 333–334. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Formisano, Ronald P. (2004) [1991]. Boston Against Busing: Race, Class, and Ethnicity in the 1960s and 1970s. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-0807855263.

- ^ Levine, Hillel; Harmon, Lawrence (1992). The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions. New York: Free Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-0029138656.

- ^ Tager, Jack (2001). Boston Riots: Three Centuries of Social Violence. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1555534615.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 121–123. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Hogarty, Richard A. (2002). Massachusetts Politics and Public Policy: Studies in Power and Leadership. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 242–246. ISBN 9781558493629.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ "Harbor Point on the Bay". Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Silva, Cristina (July 21, 2006). "UMass closes big garage in Boston". Boston.com. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 173–175. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Larkin, Max; O'Keefe, Caitlin; Chakrabarti, Meghna (April 6, 2017). "J. Keith Motley, UMass Boston Chancellor, To Step Down". WBUR. Retrieved April 7, 2017.

- ^ "UMass-Boston Cuts Summer Courses As It Grapples With Deficit". WBZ-TV. April 10, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ^ Lannan, Katie (April 24, 2017). "UMass Boston: Gov. Baker's Capital Budget Will Fund Needed Garage Repairs". WGBH. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ^ Krantz, Laura (November 15, 2017). "Caught in a financial crisis, UMass Boston begins to cut jobs". The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ Krantz, Laura (November 9, 2017). "Chaotic management led to UMass Boston deficit, audit says". The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ "Read the full statement from UMass's president on Mount Ida College". The Boston Globe. April 12, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ Creamer, Lisa; Thys, Fred (April 6, 2018). "Mount Ida College To Close; UMass Amherst To Acquire Its Campus In Newton". WBUR. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ Rios, Simón (May 3, 2018). "For Some At UMass Boston, Mount Ida Deal Stokes Feeling Of Second-Class Citizenship". WBUR. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ Sullivan, Gregory W.; Paxton, Rebekah (2019). Fiscal Crisis at UMass Boston: The True Story and the Scapegoating (PDF) (Report). Pioneer Institute. Retrieved July 28, 2021.

- ^ Feldberg, Michael (2015). UMass Boston at 50: A Fiftieth-Anniversary History of the University of Massachusetts Boston. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 978-1625341693.

- ^ Rios, Simón (April 19, 2018). "UMass Boston Students, Faculty Want UMass Amherst To Drop Mount Ida Acquisition". WBUR. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ Valencia, Crystal (January 31, 2019). "UMass Boston Returns to Military Friendly List for Sixth Time". UMass Boston News. University of Massachusetts Boston. Retrieved August 6, 2020.

- ^ "John F. Collins".

- ^ "John Collins, 76, Boston Mayor During City's Renewal in the 60's". The New York Times. November 24, 1995. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ "J.F. COLLINS DIES AT 76". The Washington Post. November 24, 1995. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- ^ "CultureNOW - Mayor John Frederick Collins: John McCormack, Boston Art Commission, City of Boston and Eduard I Browne Trust Fund". CultureNOW.org. 2004. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John F. Collins. |

- Obituary

- John F. Collins at Find a Grave

- http://www.ewtn.com/library/ISSUES/ENDIRISH.TXT

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070808222457/http://www.irishheritagetrail.com/jfcollins.htm

- NY Times Obituary

- http://www.thecrimson.com/printerfriendly.aspx?ref=492233

- Time (magazine)

- Boston Public Library. Collins, John F. (1919-1995) Collection

- 1919 births

- 1995 deaths

- United States Army personnel of World War II

- American people of Irish descent

- American politicians with physical disabilities

- Mayors of Boston

- Boston City Council members

- Members of the Massachusetts House of Representatives

- Massachusetts state senators

- Massachusetts Democrats

- Massachusetts lawyers

- MIT School of Engineering faculty

- Military personnel from Massachusetts

- Suffolk University Law School alumni

- United States Army officers

- People with polio

- Deaths from pneumonia

- 20th-century American politicians

- MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences faculty

- MIT Sloan School of Management faculty

- 20th-century American lawyers