John F. Kennedy Jr.

John F. Kennedy Jr. | |

|---|---|

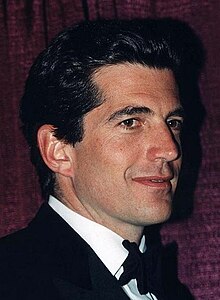

Kennedy in 1999 | |

| Born | John Fitzgerald Kennedy Jr. November 25, 1960 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Died | July 16, 1999 (aged 38) Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Plane crash |

| Alma mater | Brown University (AB) New York University (JD) |

| Occupation | Journalist, lawyer, magazine publisher |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Family | Kennedy family |

John Fitzgerald Kennedy Jr. (November 25, 1960 – July 16, 1999), often referred to as John-John or JFK Jr., was an American lawyer, journalist, and magazine publisher. He was a son of the 35th U.S. President John F. Kennedy and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, and a younger brother of Caroline Kennedy. Three days after his father was assassinated, he rendered a salute at the funeral on his third birthday.

From his childhood years at the White House, Kennedy was the subject of much media scrutiny, and later became a popular social figure in Manhattan. Trained as a lawyer, he worked as a New York City assistant district attorney for almost four years. In 1995, he launched George magazine, using his political and celebrity status to publicize it. He died in a plane crash in 1999 at the age of 38.

Early life[]

John Fitzgerald Kennedy Jr. was born at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital on November 25, 1960, two weeks after his father and namesake, Massachusetts senator John F. Kennedy, was elected president. His father took office exactly eight weeks after John Jr. was born. His parents had a stillborn daughter named Arabella four years before John Jr.'s birth. John Jr. had an older sister, Caroline, and a younger brother, Patrick, who died two days after his premature birth in 1963. His putative nickname, "John-John", came from a reporter who misheard JFK calling him "John" twice in quick succession; the name was not used by his family.[1]

John Jr. lived in the White House during the first three years of his life and remained in the public spotlight as a young adult. His father was assassinated on November 22, 1963 and the state funeral was held three days later on John Jr.'s third birthday. At his mother's prompting, John Jr. saluted the flag-draped casket as it was carried out from St. Matthew's Cathedral.[2] NBC News vice-president Julian Goodman called the video of the salute "the most impressive...shot in the history of television," which was set up by NBC Director Charles Jones, who was working for the press pool.[3] Lyndon B. Johnson wrote his first letter as president to John Jr. and told him that he "can always be proud" of his father.[4] Stan Stearns, who took an iconic photograph of the salute, served as chief White House photographer during the Johnson administration. Over the years, Stearns showed Johnson the image as it was a symbol of what Johnson said in his letter to John Jr.[5][6]

The family continued with their plans for a birthday party to demonstrate that the Kennedys would go on despite the death of the president.[7]

After President Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Jacqueline Kennedy moved her family, after a brief residency in the Georgetown area of Washington, to a luxury apartment on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City, where Kennedy Jr. grew up. In 1967, his mother took him and Caroline on a six-week "sentimental journey" to Ireland, where they met President Éamon de Valera and visited the Kennedy ancestral home in Dunganstown.[8]

Mother's remarriage[]

After Robert Kennedy was assassinated in 1968, Jackie took Caroline and John Jr. out of the United States, saying: "If they're killing Kennedys, then my children are targets ... I want to get out of this country."[9] The same year, she married Greek shipping tycoon Aristotle Onassis, and the family went to live on his private island of Skorpios. Kennedy is said to have considered his stepfather "a joke".[10] When Onassis died in 1975, he left Kennedy $25,000, though Jacqueline was able to renegotiate the will and acquired $20 million for herself and her children.[citation needed]

In 1971, Kennedy returned to the White House with his mother and sister for the first time since the assassination. President Richard Nixon's daughters gave Kennedy a tour that included his old bedroom, and Nixon showed him the Resolute desk under which his father had let him play.[11]

Education[]

Kennedy attended private schools in Manhattan, starting at Saint David's School and moving to Collegiate School, which he attended from third through tenth grade.[8] He completed his education at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. After graduating, he accompanied his mother on a trip to Africa. He rescued his group while on a pioneering course, which had gotten lost for two days without food or water.[12]

In 1976, Kennedy and his cousin visited an earthquake disaster zone at Rabinal in Guatemala, helping with heavy building work and distributing food. The local priest said that they "ate what the people of Rabinal ate and dressed in Guatemalan clothes and slept in tents like most of the earthquake victims," adding that the two "did more for their country's image" in Guatemala "than a roomful of ambassadors."[13] On his sixteenth birthday, Kennedy's Secret Service protection ended[14] and he spent the summer of 1978 working as a wrangler in Wyoming.[15] In 1979, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston was dedicated, and Kennedy made his first major speech, reciting Stephen Spender's poem "I Think Continually of Those Who Were Truly Great."[16]

Kennedy attended Brown University, where he majored in American studies.[17] There, he co-founded a student discussion group that focused on contemporary issues such as apartheid in South Africa, gun control, and civil rights. Visiting South Africa during a summer break, he was appalled by apartheid, and arranged for U.N. ambassador Andrew Young to speak about the topic at Brown.[18] By his junior year at Brown, he had moved off campus to live with several other students in a shared house,[19] and spent time at Xenon, a club owned by Howard Stein. Kennedy was initiated into Phi Psi, a local social fraternity that had been the Rhode Island Alpha Chapter of national Phi Kappa Psi fraternity until 1978.[20]

In January 1983, Kennedy's Massachusetts driver's license was suspended after he received more than three speeding summonses in a twelve-month period, and failed to appear at a hearing.[21][22] The family's lawyer explained he most likely "became immersed in exams and just forgot the date of the hearing."[23] He graduated that same year with a bachelor's degree in American studies, and then took a break, traveling to India and spending some time at the University of Delhi where he did his post graduation work and he met Mother Teresa. He also worked with some of the Kennedy special interest projects, including the East Harlem School at Exodus House and Reaching Up.[citation needed]

Career[]

After the 1984 Democratic Convention in San Francisco, Kennedy returned to New York and earned $20,000 a year in a position at the Office of Business Development, where his boss reflected that he worked "in the same crummy cubbyhole as everybody else. I heaped on the work and was always pleased."[24] From 1984 to 1986, he worked for the New York City Office of Business Development and served as deputy director of the 42nd Street Development Corporation in 1986,[25] conducting negotiations with developers and city agencies. In 1988, he became a summer associate at Manatt, Phelps, Rothenberg & Phillips, a Los Angeles law firm with strong connections to the Democratic Party. There, Kennedy worked for Charlie Manatt, his uncle Ted Kennedy's law school roommate.[24]

From 1989, Kennedy headed Reaching Up, a nonprofit group which provided educational and other opportunities for workers who helped people with disabilities. William Ebenstein, executive director of Reaching Up, said, "He was always concerned with the working poor, and his family always had an interest in helping them."

In 1989, Kennedy earned a J.D. degree from the New York University School of Law.[26] He then failed the New York bar exam twice, before passing on his third try in July 1990.[27] After failing the exam for a second time, Kennedy vowed that he would take it continuously until he was ninety-five years old or passed.[28] If he had failed a third time, he would have been ineligible to serve as a prosecutor in the Manhattan District Attorney's Office, where he worked for the next four years.[29][30] On August 29, 1991, Kennedy won his first case as a prosecutor.[31]

In the summer of 1992, he worked as a journalist and was commissioned by The New York Times to write an article about his kayaking expedition to the Åland Archipelago, where he saved one of his friends from the water when his kayak capsized.[32] He then considered creating a magazine with his friend, public-relations magnate Michael J. Berman—a plan which his mother thought too risky. In his 2000 book The Day John Died, Christopher Andersen wrote that Jacqueline had also worried that her son would die in a plane crash, and asked her longtime companion Maurice Tempelsman "to do whatever it took to keep John from becoming a pilot".[33]

Acting[]

Meanwhile, Kennedy had done a bit of acting, which was one of his passions (he had appeared in many plays while at Brown). He expressed interest in acting as a career, but his mother strongly disapproved of it, considering it an unsuitable profession.[34] On August 4, 1985, Kennedy made his New York acting debut in front of an invitation-only audience at the Irish Theater on Manhattan's West Side. Executive director of the Irish Arts Center, Nye Heron, said that Kennedy was "one of the best young actors I've seen in years".[25] Kennedy's director, Robin Saex, stated, "He has an earnestness that just shines through." Kennedy's largest acting role was playing a fictionalized version of himself in the eighth-season episode of the sitcom Murphy Brown, called "Altered States". In this episode, Kennedy visits Brown at her office, in order to promote a magazine he is publishing.

George magazine[]

In 1995, Kennedy and Michael Berman founded George, a glossy, politics-as-lifestyle and fashion monthly, with Kennedy controlling 50 percent of the shares.[34] Kennedy officially launched the magazine at a news conference in Manhattan on September 8 and joked that he had not seen so many reporters in one place since he failed his first bar exam.[35]

Each issue of the magazine contained an editor's column and interviews written by Kennedy,[36] who believed they could make politics "accessible by covering it in an entertaining and compelling way" which would allow "popular interest and involvement" to follow.[37] Kennedy did interviews with Louis Farrakhan, Billy Graham, Garth Brooks, and others.[37]

The first issue was criticized for its image of Cindy Crawford posing as George Washington in a powdered wig and ruffled shirt. In defense of the cover, Kennedy stated that "political magazines should look like Mirabella."[38]

In July 1997, Vanity Fair had published a profile of New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani, claiming that the mayor was sleeping with his press secretary (which both parties denied). Although tempted to follow up on this story, Kennedy decided against it.[39] The same month, Kennedy wrote about meeting Mother Teresa, declaring that the "three days I spent in her presence was the strongest evidence this struggling Catholic has ever had that God exists."[36]

The September 1997 issue of George centered on temptation, and featured two of Kennedy's cousins, Michael LeMoyne Kennedy and Joseph P. Kennedy II. Michael had been accused of having an affair with his children's underaged babysitter, while Joe had been accused by his ex-wife of having bullied her. John declared that both his cousins had become "poster boys for bad behavior"—believed to be the first time a member of the Kennedy family had publicly attacked another Kennedy. He said he was trying to show that press coverage of the pair was unfair, due to them being Kennedys.[40] But Joe paraphrased John's father by stating, "Ask not what you can do for your cousin, but what you can do for his magazine."[41]

Decline[]

By early 1997, Kennedy and Berman found themselves locked in a power struggle, which led to screaming matches, slammed doors, and even one physical altercation. Eventually Berman sold his share of the company, and Kennedy took on Berman's responsibilities himself. Though the magazine had already begun to decline in popularity before Berman left, his departure was followed by a rapid drop in sales.[42]

David Pecker, CEO of Hachette Filipacchi Magazines who were partners in George, said the decline was because Kennedy refused to "take risks as an editor, despite the fact that he was an extraordinary risk taker in other areas of his life." Pecker said, "He understood that the target audience for George was the eighteen-to-thirty-four-year-old demographic, yet he would routinely turn down interviews that would appeal to this age group, like Princess Diana or John Gotti Jr., to interview subjects like Dan Rostenkowski or Võ Nguyên Giáp."[42] Shortly before his death, Kennedy had been planning a series of online chats with the 2000 presidential candidates. Microsoft was to provide the technology and pay for it while receiving advertising in George.[43] After his death, the magazine was bought out by Hachette,[44] but folded in early 2001.[45]

Later life[]

Family activity[]

Kennedy addressed the 1988 Democratic National Convention in Atlanta, introducing his uncle, Senator Ted Kennedy. He invoked his father's inaugural address, calling "a generation to public service", and received a two-minute standing ovation.[46] Republican consultant Richard Viguerie said he did not remember a word of the speech, but remembered "a good delivery" and added, "I think it was a plus for the Democrats and the boy. He is strikingly handsome."[47][48]

Kennedy participated in his cousin Patrick J. Kennedy's campaign for a seat in the Rhode Island House of Representatives by visiting the district.[49] He sat outside the polling booth and had his picture taken with "would-be" voters. The polaroid ploy worked so well in the campaign that Patrick J. Kennedy used it again in 1994.

Kennedy also campaigned in Boston for his uncle's re-election to the U.S. Senate against challenger Mitt Romney in 1994. "He always created a stir when he arrived in Massachusetts," remarked Senator Kennedy.[50]

Relationships[]

While attending Brown University, Kennedy met Sally Munro, whom he dated for six years, and they visited India in 1983. While he was a student at Brown, he also met socialite Brooke Shields,[51] with whom he was later linked.

Kennedy also dated models Cindy Crawford and Julie Baker, as well as actress Sarah Jessica Parker,[52] who said she enjoyed dating Kennedy but realized he "was a public domain kind of a guy." Parker claimed to have no idea what "real fame" was until dating Kennedy and felt that she should "apologize for dating him" since it became the "defining factor in the person" she was.[53]

Kennedy had known actress Daryl Hannah since their two families had vacationed together in St. Maarten in the early '80s. After meeting again at the wedding of his aunt Lee Radziwill in 1988, they dated for five and a half years, though their relationship was complicated by her feelings for singer Jackson Browne, with whom she had lived for a time.

Also during this time, Kennedy dated Christina Haag. They had known each other as children, and she also attended Brown University.

Marriage[]

After his relationship with Daryl Hannah ended, Kennedy cohabitated with Carolyn Bessette, who worked in the fashion industry. They were engaged for a year, though Kennedy consistently denied reports of this. On September 21, 1996, they married in a private ceremony on Cumberland Island, Georgia,[54] where his sister, Caroline, was matron of honor and his cousin Anthony Radziwill was best man.[55]

The next day, Kennedy's cousin Patrick revealed that the pair had married. When they returned to their Manhattan home, a mass of reporters was on the doorstep. One of them asked Kennedy if he had enjoyed his honeymoon, to which he responded: "Very much." He added "Getting married is a big adjustment for us, and for a private citizen like Carolyn even more so. I ask you to give her all the privacy and room you can."[56]

But Carolyn was, in fact, badly disoriented by the constant attention from the paparazzi. The couple was permanently on show, both at fashionable Manhattan events, and on their travels to visit celebrities such as Mariuccia Mandelli and Gianni Versace.[57] She also complained to her friend, journalist Jonathan Soroff, that she could not get a job without being accused of exploiting her fame.[58]

In June 2019, longtime friend of John F. Kennedy Jr., Billy Noonan, released a video tape of the secret wedding that had taken place on the remote Georgian island.[59][60]

Piloting[]

Kennedy took flying lessons at the Flight Safety Academy in Vero Beach, Florida.[40] In April 1998, he received his pilot's license, which he had aspired to since he was a child.[35]

The death of his cousin Michael in a skiing accident[61] prompted John to take a hiatus from his piloting lessons for three months. His sister Caroline hoped this would be permanent, but when he resumed, she did little to stop him.[62]

Death[]

On July 16, 1999, Kennedy departed from Fairfield, New Jersey, at the controls of his Piper Saratoga light aircraft. He was traveling with his wife Carolyn and sister-in-law Lauren Bessette to attend the wedding of his cousin Rory Kennedy at Hyannis Port, Massachusetts after first dropping Lauren off in Martha's Vineyard. He had purchased the plane on April 28, 1999, from Air Bound Aviation.[63] Carolyn and Lauren were passengers sitting in the second row of seats.[64] Kennedy had checked in with the control tower at the Martha's Vineyard Airport, but the plane was reported missing after it failed to arrive on schedule.[65]

Officials were not hopeful about finding survivors after aircraft debris and a black suitcase belonging to Bessette were recovered from the Atlantic Ocean.[66] President Bill Clinton gave his support to the Kennedy family during the search for the three missing passengers.[66]

On July 18, a Coast Guard admiral declared an end to hope that Kennedy, his wife and her sister could be found alive.[67] On July 19, the fragments of Kennedy's plane were found by the NOAA vessel Rude using side-scan sonar. The next day, Navy divers descended into the 62 °F (17 °C) water. The divers found part of the shattered plane strewn over a broad area of seabed 120 feet (37 m) below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean.[68] The search ended in the late afternoon of July 21, when the three bodies were recovered from the ocean floor by Navy divers and taken by motorcade to the county medical examiner's office.[69] The discovery was made from high-resolution images of the ocean bottom.[70] Divers found Carolyn's and Lauren's bodies near the twisted and broken fuselage while Kennedy's body was still strapped into the pilot's seat.[65] Admiral Richard M. Larrabee of the Coast Guard said that all three bodies were "near and under" the fuselage, still strapped in.[71]

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined that pilot error was the probable cause of the crash: "Kennedy's failure to maintain control of the airplane during a descent over water at night, which was a result of spatial disorientation."[72]

On the evening of July 21, the bodies were autopsied at the county medical examiner's office; the findings revealed that the crash victims had died upon impact. At the same time, the Kennedy and Bessette families announced their plans for memorial services.[69] On July 21, the three bodies were taken from Hyannis to Duxbury, Massachusetts, where they were cremated in the Mayflower Cemetery crematorium.[73][74] Ted Kennedy favored a public service for John, while Caroline Kennedy insisted on family privacy.[75] On the morning of July 22, their ashes were scattered at sea from the Navy destroyer USS Briscoe off the coast of Martha's Vineyard.[76]

A memorial service was held for Kennedy on July 23, 1999, at the Church of St. Thomas More, which was a parish that Kennedy had often attended with his mother and sister. The invitation-only service was attended by hundreds of mourners, including President Bill Clinton, who presented the family with photo albums of John and Carolyn on their visit to the White House from the previous year.[77] Other guests at the church were Edward Kennedy, Arnold Schwarzenegger with Maria Shriver, Sen. John Kerry, Lee Radziwill, Maurice Tempelsman and Muhammad Ali.[78]

Kennedy's last will and testament stipulated that his personal belongings, property, and holdings were to be "evenly distributed" among his sister Caroline Kennedy's three children, who were among fourteen beneficiaries in his will.[65]

Legacy[]

In 2000, Reaching Up, the organization which Kennedy founded in 1989, joined with The City University of New York to establish the John F. Kennedy Jr. Institute.[79] In 2003, the ARCO Forum at Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government was renamed to the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum of Public Affairs. An active participant in Forum events, Kennedy had been a member of the Senior Advisory Committee of Harvard's Institute of Politics for fifteen years. Kennedy's paternal uncle, Ted, said the renaming symbolically linked Kennedy and his father while his sister, Caroline, stated the renaming represented his love of discussing politics.[80]

On the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy Jr.'s father in 2013, the New York Daily News re-ran the famous photograph of the three-year-old John F. Kennedy Jr. saluting his father's coffin during the funeral procession. Photographer Dan Farrell, who took the photo, called it "the saddest thing I've ever seen in my whole life".[81]

Conspiracy theories[]

Posthumously, Kennedy became a figure in conspiracy theories associated with the far-right QAnon movement. Proponents of these theories allege that he faked his own death and is now Q, a high-level government official with access to classified information regarding then-President Donald Trump.[82] In 2019, some QAnon followers attended Independence Day celebrations in Washington, D.C., with the expectation that Kennedy would appear on the twentieth anniversary of his death.[83][84]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Kennedy Year in Review Archived 2006-05-13 at the Wayback Machine CNN.

- ^ Lucas, Dean (July 22, 2007). "Famous Pictures Magazine – JFK Jr salutes JFK". Famous Pictures Magazine. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ NBC Executive Julian Goodman on NBC's coverage of President Kennedy's funeral-EMMYTVLEGENDS on YouTube

- ^ Miller, Merle (1980). Lyndon: An Oral Biography. New York: Putnam. p. 323.

- ^ Flegenheimer, Matt (March 5, 2012). "Stan Stearns, 76; Captured a Famous Salute". The New York Times. p. B10.

- ^ Stan Stearns - Photographer of John-John's JFK Funeral Salute on YouTube

- ^ Leamer, p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Heymann, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Seely, Katherine (July 19, 1999). "John F. Kennedy Jr., Heir to a Formidable Dynasty". The New York Times. Retrieved November 8, 2009.

- ^ Davis, p. 690.

- ^ Shane, Scott (July 18, 1999). "A life lived in celebrity". Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Leigh, p. 235.

- ^ Leigh, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Leigh, p. 137.

- ^ Landau, p. 77.

- ^ Leigh, p. 251.

- ^ Leigh, pp. 236-237.

- ^ Landau, p. 78.

- ^ Landau, p. 82.

- ^ Robert T. Littell, The Men We Became: My Friendship With John F. Kennedy, Jr. (St. Martin's Press 2004), passim.

- ^ Gillon, Steven M. (July 7, 2020). America's Reluctant Prince: The Life of John F. Kennedy Jr. Dutton. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-1524742409.

- ^ Heymann, C. David (July 10, 2007). American Legacy: The Story of John and Caroline Kennedy. Atria Books. p. 218. ISBN 978-0743497381.

- ^ Gillon, Steven M. (July 7, 2020). America's Reluctant Prince: The Life of John F. Kennedy Jr. Dutton. p. 149. ISBN 978-1524742409.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gross, Michael (March 20, 1989). "Favorite Son". New York Magazine.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bly, p. 279.

- ^ Heymann, Clemens David (2007). American Legacy: The Story of John & Caroline Kennedy. Simon and Schuster. pp. 323. ISBN 978-0-7434-9738-1.

- ^ Blow, Richard; Bradley, Richard (2002). American Son: A Portrait of John F. Kennedy, Jr. Macmillan. pp. 17. ISBN 0-312-98899-0.

- ^ "JOHN KENNEDY JR. FAILS BAR EXAM 2ND TIME; SAYS HE'LL TAKE IT AGAIN". Desert News. May 1, 1990.

- ^ "John F. Kennedy Jr. Passes Bar Exam". Los Angeles Times. November 4, 1990.

- ^ Spoto, Donald (2000). Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis: A Life. Macmillan. p. 330. ISBN 0-312-97707-7.

- ^ Sullivan, Ronald (August 30, 1991). "Prosecutor Kennedy Wins First Trial, Easily". The New York Times.

- ^ Andersen, Christopher (2014). The Good Son: JFK Jr. and the Mother He Loved. Gallery Books. pp. 266–267. ISBN 978-1476775562.

- ^ "Book: JFK. Jr's Death Foretold". ABC News. July 11, 2000.

- ^ Jump up to: a b A&E Biography

- ^ Jump up to: a b Landau, p. 117.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sumner, David E. (2010). The Magazine Century: American Magazines Since 1900. Peter Lang International Academic Publishers. pp. 201. ISBN 978-1433104930.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Landau, pp. 100-102.

- ^ Landau, p. 99.

- ^ Blow, pp. 174-175.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Andersen, p. 316.

- ^ Leigh, pp. 322-323.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Heymann, p. 438.

- ^ Blow, p. 274.

- ^ Bercovici, Jeff (2001). "Hachette delivers death ax to George" Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine. Media Life Magazine.

- ^ "Reliable Sources: 'George' Folds". CNN. January 6, 2001.

- ^ Selye, Katherine Q. (July 19, 1999). "John F. Kennedy Jr., Heir To a Formidable Dynasty". The New York Times.

- ^ Wadler, Joyce (September 12, 1988). "The Sexiest Kennedy".

- ^ "John F. Kennedy Jr. introduces his uncle Sen. Edward Kennedy (D-Mass.) at the 1988 Democratic Nation".

- ^ Bly, p. 297.

- ^ Kennedy, Edward (July 23, 1999). "The History Place - Great Speeches Collection: Ted Kennedy Speech - Tribute to JFK Junior". www.historyplace.com. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ O'Neill, Liisa (May 25, 2009). "Actress and former model Brooke Shields reveals that she didn't lose her virginity until she was 22". New York Daily News.

- ^ Landau, pp. 94-95.

- ^ Specter, Michael (September 20, 1992). "FILM; Bimbo? Sarah Jessica Parker Begs to Differ". The New York Times.

- ^ Landau, Elaine (2000). John F. Kennedy, Jr. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 117. ISBN 0-7613-1857-7.

- ^ Heymann, Clemens David (2007). American Legacy: The Story of John & Caroline Kennedy. Simon and Schuster. pp. 458. ISBN 978-0-7434-9738-1.

- ^ Heymann, p. 463.

- ^ Heymann, p. 447.

- ^ Heymann, pp. 472-473.

- ^ Hines, Ree (June 26, 2019). "See rare footage from JFK Jr. and Carolyn Bessette's fairy-tale wedding". TODAY.com.

- ^ Puente, Maria (July 14, 2019). "When JFK Jr. and Carolyn got married: Never before seen tapes on TV for first time". USA Today.

- ^ Blow, p. 301.

- ^ Heymann, p. 478-479.

- ^ Heymann, p. 32.

- ^ Heymann, p. 36.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Heymann, p. 499.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grunwald, Michael (July 18, 1999). "JFK Jr. Feared Dead in Plane Crash". The Washington Post.

- ^ Gellman, Barton (July 19, 1999). "No Hope of Survivors, Admiral Tells Families". The Washington Post.

- ^ Klein, p. 222.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Crash and Search Time Line". The Washington Post. July 22, 1999. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ^ "Divers Found Bodies". Chicago Tribune. July 22, 1999.

- ^ Allen, Mike (July 22, 1999). "Bodies From Kennedy Crash Are Found". The New York Times.

- ^ "NYC99MA178: Full Narrative". www.ntsb.gov.

- ^ Maxwell, Paula (July 28, 1999). "Kennedy cremated in Duxbury" (PDF). Duxbury Clipper. Duxbury, MA. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ^ Doing this wrong, but the preceding link is dead. Here's a copy of that report.

- ^ Landau, p. 20.

- ^ Gellman, Barton; Ferdinand, Pamela (July 23, 1999). "Kennedy, Bessettes Given Shipboard Rites". The Washington Post. pp. A1. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ Landau, p. 23.

- ^ Kleinfield, N. R. (July 24, 1999). "THE KENNEDY MEMORIAL: THE SERVICE; Doors Closed, Kennedys Offer Their Farewells". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "JFK, JR. INSTITUTE FOR WORKER EDUCATION".

- ^ Kicenuik, Kimberly A. (September 22, 2003). "ARCO Forum at IOP Renamed In Honor of John F. Kennedy Jr". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ "Daily News' iconic photo of JFK Jr.'s salute to dad's coffin still haunts". New York Daily News. November 17, 2013.

- ^ Mantyla, Kyle (August 1, 2018). "Liz Crokin: John F. Kennedy Jr. Faked His Death And Is Now QAnon". Right Wing Watch. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ Sommer, Will; Suebsaeng, Asawin; Markay, Lachlan (July 4, 2019). "This July 4th Has Everything: Tanks, Trump – and Scandal". The Daily Beast.

- ^ Dickson, E. J. (July 3, 2019). "QAnon Followers Think JFK Jr. Is Coming Back on the 4th of July". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

Works cited[]

- Blow, Richard (2002). American Son: A Portrait of John F. Kennedy, Jr. St. Martin's Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0312988999.

- Bly, Nellie (1996). The Kennedy Men: Three Generations of Sex, Scandal and Secrets. Kensington. ISBN 978-1575661063.

- Davis, John H. (1993). The Kennedys: Dynasty and Disaster. S.P.I. Books. ISBN 978-1561710607.

- Heymann, C. David (2008). American Legacy: The Story of John and Caroline Kennedy. Atria Books. ISBN 978-0743497398.

- Landau, Elaine (2000). John F. Kennedy, Jr. Millbrook Press. ISBN 978-0761318576.

- Leamer, Laurence (2005). Sons of Camelot: The Fate of an American Dynasty. William Morrow Paperbacks. ISBN 0060559020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John F. Kennedy, Jr.. |

- John F. Kennedy Jr. at IMDb

- FBI file on John F. Kennedy Jr.

- John F. Kennedy Jr. at Find a Grave

- 1960 births

- 1999 deaths

- 20th-century American lawyers

- Accidental deaths in Massachusetts

- American magazine founders

- American magazine publishers (people)

- American socialites

- Aviators from New York (state)

- Aviators killed in aviation accidents or incidents in the United States

- Bouvier family

- Brown University alumni

- Burials at sea

- Children of presidents of the United States

- Collegiate School (New York) alumni

- Kennedy family

- New York (state) lawyers

- New York University School of Law alumni

- People from the Upper East Side

- Phillips Academy alumni

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 1999

- Writers from Manhattan

- Writers from Washington, D.C.