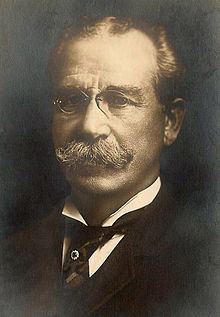

John I. Beggs

John Irvin Beggs | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 17, 1847 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Died | October 17, 1925 (aged 78) Milwaukee, Wisconsin |

| Occupation | Financier, Entrepreneur, Industrialist |

| Spouse(s) | Sue Elizabeth Charles |

John Irvin Beggs (September 17, 1847 – October 17, 1925) was an American businessman. He was associated closely with the electric utility boom under Thomas Edison. He was also associated with Milwaukee, St. Louis, Missouri and other regional rail and interurban trolley systems. Beggs is also known for developing modern depreciation techniques for business accounting and for being one of the early directors of what became General Electric.

Youth[]

John Irvin Beggs was born in Philadelphia on September 17, 1847, the son of James and Mary Irvin Beggs. Both of his parents were of Scottish descent but had emigrated to the United States from Northern Ireland.

His early life was spent around Philadelphia. After his father died when he was seven years old, Beggs worked to support of his mother in a brickyard, as a cattleman, and butcher.

Education[]

As a young man Beggs taught accounting and handwriting in the Bryant & Stratton Business College in Philadelphia. He went to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania at the age of 21 to work for Mitchell & Haggerty Coal Company as an accountant. He then worked selling real estate and fire insurance in Harrisburg. Beggs joined the Masonic fraternities at Harrisburg and maintained his membership until his death.

Electric light industry[]

When the electric light industry was in its infancy, Beggs assisted organization of the He built and managed its plant which was "the first commercially successful electric light plant in the United States". Beggs’ interest in electric lighting arose because he was head of the building committee of Grace Methodist Episcopal Church and wanted to electrify the church to save on the cost and cleanup of candles. This church became the first in the world to be wired and to use light bulbs instead of candles.

He was married in Harrisburg to Sue Elizabeth Charles, who died March 14, 1902. They had one child, Mary Grace Beggs.

On account of his success in Harrisburg as an electric plant manager, he was called by J.P. Morgan to New York City in 1886 as manager of the Edison Illuminating Company of that city. He remained in New York for about five years during which time he built two electric stations.[1] Pearl Street provided electricity for the first time to Wall Street's stockbrokers.

He worked closely with Thomas A. Edison and consequently became one of that small group known as Edison Pioneers. Beggs was one of the Illuminating Company Directors. He was also a Director at the Detroit Edison Board meeting when Henry Ford first met Edison and first pitched his idea for the automobile startup to those venture capitalists present.

Career[]

From New York he went to Chicago as Western Manager of Edison Company where he remained until the Edison Company was merged with the Thomson-Houston Electric Company to form what is now the General Electric Company.

The North American Company, which had just been organized, had acquired an electric lighting interest in Cincinnati, Ohio and Beggs went to Cincinnati in charge of these interests. The North American Company shortly afterward acquired the electric railway and lighting companies in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and for several years, Beggs divided his time between these cities. In 1897, the Cincinnati interests were sold and Beggs moved to Milwaukee to devote his time to the utilities there.

In 1903, The North American Company began to acquire electric lighting interests in St. Louis, Missouri. Beggs first visited St. Louis as an advisor, and then began to divide his time between the two cities. At one time, Beggs was president of the St. Louis electric lighting company, the gas company, and the street railway company, as well as president and general manager of The Milwaukee Electric Railway and Light Company.

While Beggs was President of the Milwaukee Companies he built the Public Service Building in Milwaukee. His funeral services were conducted in its auditorium by the . He also constructed the systems of interurban railways radiating from Milwaukee.

By 1911 Beggs had acquired a controlling interest in the St. Louis Car Company. He resigned from the Milwaukee companies and moved to St. Louis. He still maintained many business connections in Milwaukee and spent time there, although his residence was in St. Louis.

Beggs Isle[]

In the spring of 1911, Beggs purchased and named Beggs Isle in Lac La Belle, at 43°07′30″N 88°30′32″W / 43.125°N 88.509°W,[2] near Oconomowoc, Wisconsin. He developed it into a summer residence for himself and his daughter's family. Beggs turned this island into a botanical garden bringing in exotic plants. Egyptian papyrus plants were trained to last through the long Wisconsin winters. Beggs would purchase large commercial grade fireworks for their Fourth of July celebrations.[3]

In 1915, he invested in water power in northern Wisconsin and began to spend more time in that state, although still residing in St. Louis. In 1920 he was again elected president of The Milwaukee Electric Railway and Light Co., which position he still held at the time of his death.

Beggs was a member of the Executive Committee of the North American Company. He also devoted much time to the First Wisconsin National Bank in which he invested. During his last decade he directed the construction of the second largest paper mill in the country; engineered the reorganization of the J. I. Case Plow Company, arranged to finance a hotel in Atlantic City, New Jersey. and conducted a large Florida real estate transaction.[4]

Director and Officer[]

At the time of his death, Beggs was an active director or officer of 53 companies, including:

- North American Edison Company, Director (Now General Electric)

- The North American Company, Director, Member of Executive Committee

- The Milwaukee Electric Railway and Light Company, Director, President, Member of Executive Committees

- Wisconsin Gas & Electric Company, Director, Vice-President

- Briggs & Stratton Corporation, Director, Chairman Executive Committee

- St. Louis Car Company, Director, Chairman of Board

- J. I. Case Plow Works Company, Inc., Director

- Southern Improvement Company, Director, President

- First Wisconsin National Bank, Milwaukee, Director, Member of Executive and Finance Committees

- , Milwaukee, Director

- , Milwaukee, Director, Member of Executive and Finance Committees

- , Director

- , Director, President

- , Director, President

- , Director

- , Director

- , Director

- , Director

- , Director, Member of Executive Committee

- Wisconsin Public Service Corporation, Director

- , Director

- , Director

- , Baltimore, Director

- , Director

- , Director

- (Hydro-Electric), Director

- (Hydro-Electric), Director

- , Director, Member of Executive and Finance Committees

- , Director

- , Director

- , Director, President

- , Director, President

- , Director, President

- , Director, President

- , Director, President, Treasurer

- , Director

- , Director

- , Director, President

- , Director

- , Director, President

- , Director

- (Florida), Director, President

- (Bastrop, LA.), Director, President

- , Director

- , (Prescott, Ark.), Vice-President

- (Clarksville, Ark.), President

- (Atlantic City), President

Legacy[]

He died in Milwaukee on October 17, 1925 at the age of 78. He was buried in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Edison and Beggs remained friends throughout their lifetimes. On Beggs' 75th Birthday Celebration on Beggs Isle, Edison presented Beggs with a large grandfather clock and a signed photograph addressed "To my hustler friend, (signed) Thomas A. Edison".

At the time of his death, Beggs was reported to be the wealthiest man in Wisconsin, with an estimated net worth of over $20M. He passed this fortune to his grandchildren:

- Grandson Robert Paxton McCulloch (1911–1977), was responsible for McCulloch Chainsaws, the Paxton Supercharger, founding Lake Havasu City, Arizona and moving the London Bridge to Arizona.[4] He married Barbra Ann Briggs, whose father was Stephen Foster Briggs of Briggs and Stratton.

- Granddaughter Mary Sue McCulloch, "Suzie Linden" (1913–1996), author of Suzie's Story, was inducted into the Croquet Hall of Fame for founding in 1957, and operating for forty years, the Green Gables Croquet Club in Spring Lake, New Jersey, the oldest continuously running club in the USA.[5] Also, a founding member of the USCA. In 1931, she first married Whip Jones who went on to found Aspen Highlands in Aspen, Colorado and was inducted into the Aspen Hall of Fame [1] and the Colorado Ski Hall of Fame[2]. Subsequent husbands were New York investment banker and attorney James Lowell Oakes (father of judge James L. Oakes), World War II veteran , and Portland banker .

- Grandson (1908–1983), became fluent in over 10 foreign languages. After graduating from Yale, in 1933 he married Whip's sister Elizabeth Ten Broeck Jones. He became a foreign political analyst and a prolific writer of books and articles in many languages. Later in his career he supported the English Speaking Union pushing for the wider use of English.

These three had another notable grandfather, (1841–1914) who was the only confederate officer to survive the High Tide of Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg.[6] Both grandfathers were active in Freemasonry.

Filmography[]

- The Trolley at East Troy (1986) at IMDb - 1986 documentary, directed by Louis Rugani. Through the use of archival footage John I. Beggs 'stars' in this look at the history and survival efforts of this small anachronistic Wisconsin trolley line since 1907, and an overview of its relationship to the surrounding area, the now-dissolved parent company which built it, and the vanished traction empire of which it was a small part.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Ken Riedl, William F. Jannke III, Watertown History Annual 2: Hometown Series of Publications, pages 13-19

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Beggs Island Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ John I. Beggs (1910–1912). "Personal Correspondence" (bound carbon copies)

|format=requires|url=(help). Original. Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b Linden, Mary Sue McCulloch (1992). Suzie's Story:The Autobiography of Socialite, Philanthropist & World Traveler. Rainbow Books. pp. 7–10. ISBN 0-935834-87-7.

- ^ Karen Kaplan (September 2004). The New York Croquet Club History (PDF). p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2007. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ Bruce McCulloch Jones, Editor (July 2013). The High Tide at Gettysburg (PDF). Memorial packet and first hand account of Gettysburg (Battle 1863) and (Reconciliation 1913). Amazon. p. 29. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

Further reading[]

- Forrest McDonald (1957). Let there be light: The electric utility industry in Wisconsin, 1881-1955. American History Research Center.

- Bruce McCulloch Jones (2013). The High Tide at Gettysburg. Amazon.

- In Memoriam, John Irvin Beggs (1926), 49 pages, with Photo

- Watertown History Annual 2: Hometown Series of Publications, By Ken Riedl, William F. Jannke III, pages 13-19

External links[]

- Biographical sketch from Wisconsin Historical Society

- "Beggs Isle, Lac La Belle, Oconomowoc, Wis (1927)". Oconomowoc Historical Society. June 12, 2006. Archived from the original on October 3, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- 1847 births

- 1925 deaths

- American technology chief executives

- American energy industry executives

- American financiers

- American people of Scottish descent

- American railroad executives of the 20th century

- American real estate businesspeople

- Edison Pioneers

- People from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- Businesspeople from Milwaukee

- People from Oconomowoc, Wisconsin

- Businesspeople from Philadelphia

WikiMiniAtlas

WikiMiniAtlas