Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker | |

|---|---|

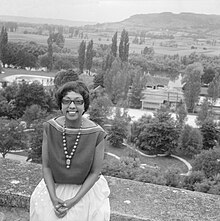

Baker in 1940 | |

| Born | Freda Josephine McDonald 3 June 1906 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | 12 April 1975 (aged 68) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Monaco Cemetery |

| Nationality | American (renounced) French (1937–1975) |

| Occupation | Vedette, singer, dancer, actress, civil rights activist, French Resistance agent |

| Years active | 1921–1975 |

| Spouse(s) | Willie Wells

(m. 1919; div. 1919)William Baker

(m. 1921; div. 1925)Jean Lion

(m. 1937; div. 1940) |

| Partner(s) | Robert Brady (1973–1975) |

| Children | 12 (adopted), including Jean-Claude Baker |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments | Vocals |

| Labels | |

Josephine Baker (born Freda Josephine McDonald, naturalised French Joséphine Baker; 3 June 1906 – 12 April 1975) was an American-born French entertainer, French Resistance agent, and civil rights activist. Her career was centered primarily in Europe, mostly in her adopted France. She was the first Black woman to star in a major motion picture, the 1927 silent film Siren of the Tropics, directed by Mario Nalpas and Henri Étiévant.[1]

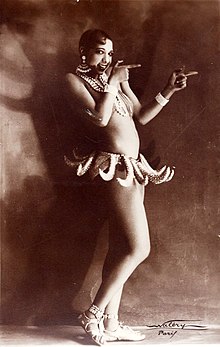

During her early career, Baker was renowned as a dancer, and was among the most celebrated performers to headline the revues of the Folies Bergère in Paris. Her performance in the revue Un vent de folie in 1927 caused a sensation in the city. Her costume, consisting of only a short skirt of artificial bananas and a beaded necklace, became an iconic image and a symbol both of the Jazz Age and the Roaring Twenties.

Baker was celebrated by artists and intellectuals of the era, who variously dubbed her the "Black Venus", the "Black Pearl", the "Bronze Venus", and the "Creole Goddess". Born in St. Louis, Missouri, she renounced her U.S. citizenship and became a French national after her marriage to French industrialist Jean Lion in 1937.[2] She raised her children in France.

She was known for aiding the French Resistance during World War II.[3] After the war, she was awarded the Resistance Medal by the French Committee of National Liberation, the Croix de guerre by the French military, and was named a Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur by General Charles de Gaulle.[4] Baker sang: "I have two loves, my country and Paris."[5]

Baker refused to perform for segregated audiences in the United States and is noted for her contributions to the civil rights movement. In 1968, she was offered unofficial leadership in the movement in the United States by Coretta Scott King, following Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination. After thinking it over, Baker declined the offer out of concern for the welfare of her children.[6][7]

On 23 August 2021, it was announced that in November 2021 she will be interred in the Panthéon in Paris, the first black woman to receive one of the highest honors in France.[8]

Early life[]

Freda Josephine McDonald was born in St. Louis, Missouri.[6][9][10] Her mother, Carrie, was adopted in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1886 by Richard and Elvira McDonald, both of whom were former slaves of African and Native American descent.[6] Baker's estate identifies vaudeville drummer Eddie Carson as her natural father despite evidence to the contrary.[11] Baker's foster son Jean-Claude Baker wrote a biography, published in 1993, titled Josephine: The Hungry Heart. Jean-Claude Baker did an exhaustive amount of research into the life of Josephine Baker, including the identity of her biological father. In the book, he discusses at length the circumstances surrounding Baker's birth:

The records of the city of St. Louis tell an almost unbelievable story. They show that (Baker's mother) Carrie McDonald ... was admitted to the (exclusively white) Female Hospital on May 3, 1906, diagnosed as pregnant. She was discharged on June 17, her baby, Freda J. McDonald having been born two weeks earlier. Why six weeks in the hospital? Especially for a black woman (of that time) who would customarily have had her baby at home with the help of a midwife? ... The father was identified (on the birth certificate) simply as "Edw"... I think Josephine's father was white – so did Josephine, so did her family ... people in St. Louis say that (Baker's mother) had worked for a German family (around the time she became pregnant)... I have unraveled many mysteries associated with Josephine Baker, but the most painful mystery of her life, the mystery of her father's identity, I could not solve. The secret died with Carrie, who refused to the end to talk about it. She let people think Eddie Carson was the father, and Carson played along, (but) Josephine knew better.[6]

Josephine spent her early life at 212 Targee Street (known by some St. Louis residents as Johnson Street) in the Mill Creek Valley neighborhood of St. Louis, a racially mixed low-income neighborhood near Union Station, consisting mainly of rooming houses, brothels, and apartments without indoor plumbing.[6] Josephine was poorly dressed and hungry as a child, and developed street smarts playing in the railroad yards of Union Station.[12]

Josephine's mother married Arthur Martin, "a kind but perpetually unemployed man", with whom she had a son and two more daughters.[13] She took in laundry to wash to make ends meet, and at eight years old, Josephine began working as a live-in domestic for white families in St. Louis.[14] One woman abused her, burning Josephine's hands when the young girl put too much soap in the laundry.[15]

In 1917, when she was 11, a terrified Josephine witnessed racial violence in East St. Louis, Illinois.[16] In a speech years later, she recalled what she had seen:

"I can still see myself standing on the west bank of the Mississippi looking over into East St. Louis and watching the glow of the burning of Negro homes lighting the sky. We children stood huddled together in bewilderment . . . frightened to death with the screams of the Negro families running across this bridge with nothing but what they had on their backs as their worldly belongings . . . So with this vision I ran and ran and ran. . ."[17]

By age 12, she had dropped out of school.[18][19]

At 13, she worked as a waitress at the Old Chauffeur's Club at 3133 Pine Street. She also lived as a street child in the slums of St. Louis, sleeping in cardboard shelters, scavenging for food in garbage cans,[20] making a living with street-corner dancing. It was at the Old Chauffeur's Club where Josephine met Willie Wells, and subsequently married him at age 13; however, the marriage lasted less than a year. Following her divorce from Wells, she found work with a street performance group called the Jones Family Band.[21]

In Baker's teen years she struggled to have a healthy relationship with her mother, who did not want Josephine to become an entertainer, and scolded her for not tending to her second husband, Willie Baker, whom she married in 1921 at the age of 15.[22] She left him when her vaudeville troupe was booked into a New York City venue and divorced in 1925; it was during this time she began to see significant career success, and she continued to use his last name professionally for the rest of her life.[6] Though Baker traveled, she would return with gifts and money for her mother and younger half-sister, but the turmoil with her mother pushed her to make a trip to France.[23]

Career[]

Early years[]

Baker's consistent badgering of a show manager in her hometown led to her being recruited for the St. Louis Chorus vaudeville show. At the age of 13, she headed to New York City [17] during the Harlem Renaissance, performing at the Plantation Club, Florence Mills' old stomping ground, and in the chorus lines of the groundbreaking and hugely successful Broadway revues Shuffle Along (1921)[24] with Adelaide Hall[25] and The Chocolate Dandies (1924).

Baker performed as the last dancer on the end of the chorus line, where her act was to perform in a comic manner, as if she were unable to remember the dance, until the encore, at which point she would perform it not only correctly but with additional complexity. A term of the time describes this part of the cast as "The Pony". Baker was billed at the time as "the highest-paid chorus girl in vaudeville."[6]

Her career began with blackface comedy at local clubs; this was the entertainment of which her mother had disapproved; however, these performances landed Baker an opportunity to tour in Paris, which would become the place she called home until her final days.[26]

Paris and rise to fame[]

Baker sailed to Paris for a new venture, and opened in La Revue Nègre on 2 October 1925, aged 19, at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.[27][28]

In a 1974 interview with The Guardian, Baker explained that she obtained her first big break in the bustling city. "No, I didn't get my first break on Broadway. I was only in the chorus in 'Shuffle Along' and 'Chocolate Dandies'. I became famous first in France in the twenties. I just couldn't stand America and I was one of the first colored Americans to move to Paris. Oh yes, Bricktop was there as well. Me and her were the only two, and we had a marvellous time. Of course, everyone who was anyone knew Bricky. And they got to know Miss Baker as well."[29]

In Paris, she became an instant success for her erotic dancing, and for appearing practically nude onstage. After a successful tour of Europe, she broke her contract and returned to France in 1926 to star at the Folies Bergère, setting the standard for her future acts.[6]

Baker performed the "Danse Sauvage" wearing a costume consisting of a skirt made of a string of artificial bananas. Her success coincided (1925) with the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, which gave birth to the term "Art Deco", and also with a renewal of interest in non-Western forms of art, including African. Baker represented one aspect of this fashion. In later shows in Paris, she was often accompanied on stage by her pet cheetah "Chiquita," who was adorned with a diamond collar. The cheetah frequently escaped into the orchestra pit, where it terrorized the musicians, adding another element of excitement to the show.[6]

After a while, Baker was the most successful American entertainer working in France. Ernest Hemingway called her "the most sensational woman anyone ever saw."[30][31] The author spent hours talking with her in Paris bars. Picasso drew paintings depicting her alluring beauty. Jean Cocteau became friendly with her and helped vault her to international stardom.[32]

In 1929, Baker became the first African-American star to visit Yugoslavia, while on tour in Central Europe via the Orient Express. In Belgrade, she performed at , the most luxurious venue in the city at the time. She included Pirot kilim into her routine, as a nod to the local culture, and she donated some of the show's proceeds to poor children of Serbia. In Zagreb, she was received by adoring fans at the train station. However, some of her shows were cancelled, due to opposition from the local clergy and morality police.[33]

During her travels in Yugoslavia, Baker was accompanied by "Count" Giuseppe Pepito Abatino.[33] At the start of her career in France, Baker had Abatino, a Sicilian former stonemason who passed himself off as a count, and who persuaded her to let him manage her.[23] Abatino was not only Baker's management, but her lover as well. The two could not marry because Baker was still married to her second husband, Willie Baker.[22]

During this period, she scored her most successful song, "J'ai deux amours" (1931).[34] Baker starred in three films which found success only in Europe: the silent film Siren of the Tropics (1927), Zouzou (1934) and Princesse Tam Tam (1935). She starred in in 1940.[35]

Under the management of Abatino, Baker's stage and public persona, as well as her singing voice, were transformed. In 1934, she took the lead in a revival of Jacques Offenbach's opera La créole, which premiered in December of that year for a six-month run at the Théâtre Marigny on the Champs-Élysées of Paris. In preparation for her performances, she went through months of training with a vocal coach. In the words of Shirley Bassey, who has cited Baker as her primary influence, "... she went from a 'petite danseuse sauvage' with a decent voice to 'la grande diva magnifique' ... I swear in all my life I have never seen, and probably never shall see again, such a spectacular singer and performer."[36]

Despite her popularity in France, Baker never attained the equivalent reputation in America. Her star turn in a 1936 revival of Ziegfeld Follies on Broadway generated less than impressive box office numbers, and later in the run, she was replaced by Gypsy Rose Lee.[37][38] Time magazine referred to her as a "Negro wench ... whose dancing and singing might be topped anywhere outside of Paris", while other critics said her voice was "too thin" and "dwarf-like" to fill the Winter Garden Theatre.[37] She returned to Europe heartbroken.[27] This contributed to Baker's becoming a legal citizen of France and giving up her American citizenship.[6]

Baker returned to Paris in 1937, married the French industrialist Jean Lion, and became a French citizen.[39] They were married in the French town of Crèvecœur-le-Grand, in a wedding presided over by the mayor, Jammy Schmidt.

Work during World War II[]

In September 1939, when France declared war on Germany in response to the invasion of Poland, Baker was recruited by the Deuxième Bureau, the French military intelligence agency, as an "honorable correspondent". Baker collected what information she could about German troop locations from officials she met at parties. She socialised at gatherings at locations such as embassies and ministries, charming people while secretly gathering information. Her café-society fame enabled her to rub shoulders with those in the know, from high-ranking Japanese officials to Italian bureaucrats, and to report back what she heard. She attended parties and gathered information at the Italian embassy without raising suspicion.[40]:182–269

When the Germans invaded France, Baker left Paris and went to the Château des Milandes, her home in the Dordogne département in the south of France. She housed people who were eager to help the Free French effort led by Charles de Gaulle and supplied them with visas.[41] As an entertainer, Baker had an excuse for moving around Europe, visiting neutral nations such as Portugal, as well as some in South America. She carried information for transmission to England, about airfields, harbors, and German troop concentrations in the West of France. Notes were written in invisible ink on Baker's sheet music.[40]:232–269 As written in Jazz Age Cleopatra, "She specialized in gatherings at embassies and ministries, charming people as she had always done, but at the same time trying to remember interesting items to transmit."[33]

Later in 1941, she and her entourage went to the French colonies in North Africa. The stated reason was Baker's health (since she was recovering from another case of pneumonia) but the real reason was to continue helping the Resistance. From a base in Morocco, she made tours of Spain. She pinned notes with the information she gathered inside her underwear (counting on her celebrity to avoid a strip search). She met the Pasha of Marrakech, whose support helped her through a miscarriage (the last of several). After the miscarriage, she developed an infection so severe it required a hysterectomy. The infection spread and she developed peritonitis and then sepsis. After her recovery (which she continued to fall in and out of), she started touring to entertain British, French, and American soldiers in North Africa. The Free French had no organized entertainment network for their troops, so Baker and her entourage managed for the most part on their own. They allowed no civilians and charged no admission.[40]

After the war, Baker received the Croix de guerre and the Rosette de la Résistance. She was made a Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur by General Charles de Gaulle.[42]

Baker's last marriage, to French composer and conductor Jo Bouillon, ended around the time Baker opted to adopt her 11th child.[22]

Later career[]

In 1949, a reinvented Baker returned in triumph to the Folies Bergère. Bolstered by recognition of her wartime heroism, Baker the performer assumed a new gravitas, unafraid to take on serious music or subject matter. The engagement was a rousing success and reestablished Baker as one of Paris' pre-eminent entertainers. In 1951 Baker was invited back to the United States for a nightclub engagement in Miami. After winning a public battle over desegregating the club's audience, Baker followed up her sold-out run at the club with a national tour. Rave reviews and enthusiastic audiences accompanied her everywhere, climaxed by a parade in front of 100,000 people in Harlem in honor of her new title: NAACP's "Woman of the Year".[43][44]

In 1952 Baker was hired to crown the Queen of the Cavalcade of Jazz for the famed eighth Cavalcade of Jazz concert held at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles which was produced by Leon Hefflin, Sr. on 1 June. Also featured to perform that day were Roy Brown and His Mighty Men, Anna Mae Winburn and Her Sweethearts, Toni Harper, Louis Jordan, Jimmy Witherspoon and Jerry Wallace.[45][46]

An incident at the Stork Club in October 1951 interrupted and overturned her plans. Baker criticized the club's unwritten policy of discouraging Black patrons, then scolded columnist Walter Winchell, an old ally, for not rising to her defense. Winchell responded swiftly with a series of harsh public rebukes, including accusations of Communist sympathies (a serious charge at the time). The ensuing publicity resulted in the termination of Baker's work visa, forcing her to cancel all her engagements and return to France. It was almost a decade before U.S. officials allowed her back into the country.[47]

In January 1966, Fidel Castro invited Baker to perform at the Teatro Musical de La Habana in Havana, Cuba, at the seventh-anniversary celebrations of his revolution. Her spectacular show in April broke attendance records. In 1968, Baker visited Yugoslavia and made appearances in Belgrade and in Skopje. In her later career, Baker faced financial troubles. She commented, "Nobody wants me, they've forgotten me"; but family members encouraged her to continue performing. In 1973 she performed at Carnegie Hall to a standing ovation.[40]

The following year, she appeared in a Royal Variety Performance at the London Palladium, and then at the Monegasque Red Cross Gala, celebrating her 50 years in French show business. Advancing years and exhaustion began to take their toll; she sometimes had trouble remembering lyrics, and her speeches between songs tended to ramble. She still continued to captivate audiences of all ages.[40]

Civil rights activism[]

Although based in France, Baker supported the Civil Rights Movement during the 1950s. When she arrived in New York with her husband Jo, they were refused reservations at 36 hotels because of racial discrimination. She was so upset by this treatment that she wrote articles about the segregation in the United States. She also began traveling into the South. She gave a talk at Fisk University, a historically Black college in Nashville, Tennessee, on "France, North Africa and the Equality of the Races in France."[40]

She refused to perform for segregated audiences in the United States, although she was offered $10,000 by a Miami club.[3] (The club eventually met her demands). Her insistence on mixed audiences helped to integrate live entertainment shows in Las Vegas, Nevada.[7] After this incident, she began receiving threatening phone calls from people claiming to be from the Ku Klux Klan but said publicly that she was not afraid of them.[40]

In 1951, Baker made charges of racism against Sherman Billingsley's Stork Club in Manhattan, where she had been refused service.[47][48] Actress Grace Kelly, who was at the club at the time, rushed over to Baker, took her by the arm and stormed out with her entire party, vowing never to return (although she returned on 3 January 1956 with Prince Rainier of Monaco). The two women became close friends after the incident.[49]

When Baker was near bankruptcy, Kelly—by then the princess consort—offered her a villa and financial assistance. (During his work on the Stork Club book, author and New York Times reporter Ralph Blumenthal was contacted by Jean-Claude Baker, one of Baker's sons. He indicated that he had read his mother's FBI file and, using comparison of the file to the tapes, said he thought the Stork Club incident was overblown.[50])

Baker also worked with the NAACP.[3] Her reputation as a crusader grew to such an extent that the NAACP had Sunday, 20 May 1951 declared "Josephine Baker Day." She was presented with life membership with the NAACP by Nobel Peace Prize winner Dr. Ralph Bunche. The honor she was paid spurred her to further her crusading efforts with the "Save Willie McGee" rally. McGee was a Black man in Mississippi convicted of raping a white woman in 1945 on the basis of dubious evidence, and sentenced to death.[51] Baker attended rallies for McGee and wrote letters to Fielding Wright, the governor of Mississippi, asking him to spare McGee's life.[51] Despite her efforts, McGee was executed in 1951.[51] As the decorated war hero who was bolstered by the racial equality she experienced in Europe, Baker became increasingly regarded as controversial; some Black people even began to shun her, fearing that her outspokenness and racy reputation from her earlier years would hurt the cause.[40]

In 1963, she spoke at the March on Washington at the side of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.[52] Baker was the only official female speaker. While wearing her Free French uniform emblazoned with her medal of the Légion d'honneur, she introduced the "Negro Women for Civil Rights."[53] Rosa Parks and Daisy Bates were among those she acknowledged, and both gave brief speeches.[54] Not everyone involved wanted Baker present at the March; some thought her time overseas had made her a woman of France, one who was disconnected from the Civil Rights issues going on in America. In her powerful speech, one of the things Baker notably said was:

I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents. And much more. But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad. And when I get mad, you know that I open my big mouth. And then look out, 'cause when Josephine opens her mouth, they hear it all over the world ...[55][56]

After King's assassination, his widow Coretta Scott King approached Baker in the Netherlands to ask if she would take her husband's place as leader of the Civil Rights Movement. After many days of thinking it over, Baker declined, saying her children were "too young to lose their mother."[54]

Personal life[]

Relationships[]

Her first marriage was to American Pullman porter Willie Wells when she was only 13 years old. The marriage was reportedly very unhappy and the couple divorced a short time later. Another short-lived marriage followed to Willie Baker in 1921; she retained Baker's last name because her career began taking off during that time, and it was the name by which she became best known. While she had four marriages to men, Jean-Claude Baker writes that Josephine was bisexual and had several relationships with women.[57]

During her time in the Harlem Renaissance arts community, one of her relationships was with Blues singer Clara Smith.[57] In 1925, she began an extramarital relationship with the Belgian novelist Georges Simenon.[58] In 1937, Baker married Frenchman Jean Lion. She and Lion separated in 1940. She married French composer and conductor Jo Bouillon in 1947, and their union also ended in divorce but lasted 14 years. She was later involved for a time with the artist Robert Brady, but they never married.[59] Baker was also involved in sexual liaisons, if not relationships, with Ada "Bricktop" Smith, French novelist Colette, and possibly Frida Kahlo.[60]

Children[]

During Baker's work with the Civil Rights Movement, she began adopting children, forming a family she often referred to as "The Rainbow Tribe." Baker wanted to prove that "children of different ethnicities and religions could still be brothers." She often took the children with her cross-country, and when they were at Château des Milandes, she arranged tours so visitors could walk the grounds and see how natural and happy the children in "The Rainbow Tribe" were.[61] Her estate featured hotels, a farm, rides, and the children singing and dancing for the audience. She charged admission for visitors to enter and partake in the activities, which included watching the children play.[62] She created dramatic backstories for them, picking them with clear intent in mind: at one point she wanted and planned to get a Jewish baby, but settled for a French one instead. She also raised them with different religions to further her model for the world, taking two children from Algeria and raising one Muslim and the other Catholic. One member of the Tribe, Jean-Claude Baker, said: "She wanted a doll."[63]

Baker raised two daughters, French-born Marianne and Moroccan-born Stellina, and 10 sons, Korean-born Jeannot (or Janot), Japanese-born Akio, Colombian-born Luis, Finnish-born Jari (now Jarry), French-born Jean-Claude, Noël and Moïse, Algerian-born Brahim, Ivorian-born Koffi, and Venezuelan-born Mara.[64][65] For some time, Baker lived with her children and an enormous staff in the château in Dordogne, France, with her fourth husband, Jo Bouillon. Baker bore only one child herself, stillborn in 1941, an incident that precipitated an emergency hysterectomy.[66]

Later years and death[]

In her later years, Baker converted to Catholicism.[67] In 1968, Baker lost her castle owing to unpaid debts; afterwards Princess Grace offered her an apartment in Roquebrune, near Monaco.[68]

Baker was back on stage at the Olympia in Paris in 1968, in Belgrade and at Carnegie Hall in 1973, and at the Royal Variety Performance at the London Palladium and at the Gala du Cirque in Paris in 1974. On 8 April 1975, Baker starred in a retrospective revue at the Bobino in Paris, Joséphine à Bobino 1975, celebrating her 50 years in show business. The revue, financed notably by Prince Rainier, Princess Grace, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, opened to rave reviews. Demand for seating was such that fold-out chairs had to be added to accommodate spectators. The opening-night audience included Sophia Loren, Mick Jagger, Shirley Bassey, Diana Ross, and Liza Minnelli.[69]

Four days later, Baker was found lying peacefully in her bed surrounded by newspapers with glowing reviews of her performance. She was in a coma after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. She was taken to Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, where she died, aged 68, on 12 April 1975.[69][70]

She received a full Catholic funeral that was held at L'Église de la Madeleine, attracting more than 20,000 mourners.[67][71][72] The only American-born woman to receive full French military honors at her funeral, Baker's funeral was the occasion of a huge procession. After a family service at Saint-Charles Church in Monte Carlo,[73] Baker was interred at Monaco's Cimetière de Monaco.[69][74][75]

Legacy[]

Place Joséphine Baker (48°50′29″N 2°19′26″E / 48.84135°N 2.32375°E) in the Montparnasse Quarter of Paris was named in her honor. She has also been inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame,[76] and on 29 March 1995, into the Hall of Famous Missourians.[77] St. Louis's Channing Avenue was renamed Josephine Baker Boulevard[78] and a wax sculpture of Baker is on permanent display at The Griot Museum of Black History.

In 2015 she was inducted into the Legacy Walk in Chicago, Illinois.[79] The Piscine Joséphine Baker is a swimming pool along the banks of the Seine in Paris named after her.[80]

Writing in the on-line BBC magazine in late 2014, Darren Royston, historical dance teacher at RADA credited Baker with being the Beyoncé of her day, and bringing the Charleston to Britain.[81] Two of Baker's sons, Jean-Claude and Jarry (Jari), grew up to go into business together, running the restaurant Chez Josephine on Theatre Row, 42nd Street, New York City. It celebrates Baker's life and works.[82]

Château des Milandes, a castle near Sarlat in the Dordogne, was Baker's home where she raised her twelve children. It is open to the public and displays her stage outfits including her banana skirt (of which there are apparently several). It also displays many family photographs and documents as well as her Legion of Honour medal. Most rooms are open for the public to walk through including bedrooms with the cots where her children slept, a huge kitchen, and a dining room where she often entertained large groups. The bathrooms were designed in art deco style but most rooms retained the French chateau style.[83][84]

Baker continued to influence celebrities more than a century after her birth. In a 2003 interview with USA Today, Angelina Jolie cited Baker as "a model for the multiracial, multinational family she was beginning to create through adoption."[85] Beyoncé performed Baker's banana dance at the Fashion Rocks concert at Radio City Music Hall in September 2006.[85]

Writing on the 110th anniversary of her birth, Vogue described how her 1926 "danse sauvage" in her famous banana skirt "brilliantly manipulated the white male imagination" and "radically redefined notions of race and gender through style and performance in a way that continues to echo throughout fashion and music today, from Prada to Beyoncé."[86]

On 3 June 2017, the 111th anniversary of her birth, Google released an animated Google Doodle, which consists of a slideshow chronicling her life and achievements.[87]

On Thursday 22 November 2018, a documentary titled Josephine Baker: The Story of an Awakening, directed by Ilana Navaro, premiered at the Beirut Art Film Festival. It contains rarely seen archival footage, including some never before discovered, with music and narration.[88]

In August 2019, Baker was one of the honorees inducted in the Rainbow Honor Walk, a walk of fame in San Francisco's Castro neighborhood noting LGBTQ people who have "made significant contributions in their fields."[89][90][91]

In May 2021, an online petition was setup by writer Laurent Kupferman asking that Joséphine Baker be honoured by re-burying her at the Panthéon in Paris, or being granted Panthéon honours. This would make her the only sixth woman at the mausoleum, alongside Simone Veil, Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, Marie Curie, Germaine Tillion and Sophie Berthelot.[92] In August 2021, French President Emmanuel Macron agreed for Baker's remains to enter the Panthéon in November of the same year, following the 2021 petition and continued requests from Baker's family since 2013.[93] Her son Jean-Claude, however, told AFP that her body will remain in Monaco and only a plaque will be installed at the Panthéon.[94]

Portrayals[]

- Alexander Calder created Josephine Baker (III), a wire sculpture of Baker, in 1927.[95]

- Henri Matisse created a mural-sized cut paper artwork titled La Négresse (1952–1953) inspired by Baker.

- Baker appears in her role as a member of the French Resistance in Johannes Mario Simmel's 1960 novel, Es muss nicht immer Kaviar sein (C'est pas toujours du caviar).[96]

- The Italian-Belgian francophone singer composer Salvatore Adamo pays tribute to Baker with the song "Noël Sur Les Milandes" (album Petit Bonheur – EMI 1970).

- The British band 'Sailor' paid tribute on their 1974 self-titled debut album 'Sailor' with the Georg Kajanus song 'Josephine Baker' who "...stunned the world at the Folies Bergere..."

- Diana Ross portrayed Baker in both her Tony Award-winning Broadway and television show An Evening with Diana Ross. When the show was made into an NBC television special entitled The Big Event: An Evening with Diana Ross, Ross again portrayed Baker.[97]

- A German submariner mimics Baker's Danse banane in the 1981 film Das Boot.[98]

- In 1986, Helen Gelzer[99] portrayed Baker on the London stage for a limited run in the musical Josephine – "a musical version of the life and times of Josephine Baker" with book, lyrics and music by Michael Wild.[100] The show was produced by Baker's longtime friend Jack Hockett[101] in conjunction with Premier Box-Office, and the musical director was Paul Maguire. Gelzer also recorded a studio cast album titled Josephine.

- British singer-songwriter, Al Stewart wrote song about Josephine Baker. It appears in album "Last days of the century" from 1988.

- In 1991, Baker's life story, The Josephine Baker Story, was broadcast on HBO. Lynn Whitfield portrayed Baker, and won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Miniseries or a Special – becoming the first Black actress to win the award in this category.

- Artist Hassan Musa depicted Baker in a 1994 series of paintings called Who needs Bananas?[102]

- In the 1997 animated musical film Anastasia, Baker appears with her cheetah during the musical number "Paris Holds the Key (to Your Heart)".[103]

- In 2002, Baker was portrayed by Karine Plantadit in the biopic Frida.[104][105]

- A character based on Baker (topless, wearing the famous "banana skirt") appears in the opening sequence of the 2003 animated film The Triplets of Belleville (Les Triplettes de Belleville).[106]

- The 2004 erotic novel Scandalous by British author Angela Campion uses Baker as its heroine and is inspired by Baker's sexual exploits and later adventures in the French Resistance. In the novel, Baker, working with a fictional Black Canadian lover named Drummer Thompson, foils a plot by French fascists in 1936 Paris.[107]

- Her influence upon and assistance with the careers of husband and wife dancers Carmen De Lavallade and Geoffrey Holder are discussed and illustrated in rare footage in the 2005 Linda Atkinson/Nick Doob documentary, Carmen and Geoffrey.[108][109]

- Beyoncé has portrayed Baker on various occasions. During the 2006 Fashion Rocks show, Knowles performed "Dejá Vu" in a revised version of the Danse banane costume. In Knowles's video for "Naughty Girl", she is seen dancing in a huge champagne glass à la Baker. In I Am ... Yours: An Intimate Performance at Wynn Las Vegas, Beyonce lists Baker as an influence of a section of her live show.[110]

- In 2006, Jérôme Savary produced a musical, A La Recherche de Josephine – New Orleans for Ever (Looking for Josephine), starring Nicolle Rochelle. The story revolved around the history of jazz and Baker's career.[111][112]

- In 2006, Deborah Cox starred in the musical Josephine at Florida's Asolo Theatre, directed and choreographed by Joey McKneely, with a book by Ellen Weston and Mark Hampton, music by Steve Dorff and lyrics by John Bettis.[113]

- In 2010, Keri Hilson portrayed Baker in her single "Pretty Girl Rock".[114]

- In 2011, Sonia Rolland portrayed Baker in the film Midnight in Paris.[115][116]

- Baker was heavily featured in the 2012 book Josephine's Incredible Shoe & The Blackpearls by Peggi Eve Anderson-Randolph.[117]

- In July 2012, Cheryl Howard opened in The Sensational Josephine Baker, written and performed by Howard and directed by Ian Streicher at the Beckett Theatre of Theatre Row on 42nd Street in New York City, just a few doors away from Chez Josephine.[118][119]

- In July 2013, Cush Jumbo's debut play Josephine and I premiered at the Bush Theatre, London.[120] It was re-produced in New York City at The Public Theater's Joe's Pub from 27 February to 5 April 2015.[121]

- In June 2016, Josephine, a burlesque cabaret dream play starring Tymisha Harris as Josephine Baker premiered at the 2016 San Diego Fringe Festival. The show has since played across North America and had a limited off-Broadway run in January–February 2018 at SoHo Playhouse in New York City.[122]

- In February 2017, Tiffany Daniels portrayed Baker in the Timeless television episode "The Lost Generation".[123]

- In late February 2017, a new play about Baker's later years, The Last Night of Josephine Baker by playwright Vincent Victoria, opened in Houston, Texas,[124] starring Erica Young as "Past Josephine" and Jasmin Roland as "Present Josephine".[125]

- Baker appears as a recruitable secret agent with French citizenship in the 2020 DLC La Resistance for the WWII grand strategy game Hearts of Iron IV.

- Actress DeQuina Moore portrayed Baker in a biographic musical titled "Josephine Tonight" at The Ensemble Theatre in Houston, Texas, from 27 June– 28 July 2019.[126]

- Baker is portrayed by actress in the seventh episode, entitled “I Am.”, of HBO’s television series Lovecraft Country.[127]

Film credits[]

- Siren of the Tropics (1927)[128]

- The Woman from the Folies Bergères (1927) short subject

- Parisian Pleasures (1927)

- Zouzou (1934)[35]

- Princesse Tam Tam (1935)[35]

- Fausse alerte (The French Way) (1945)[129]

- Moulin Rouge (1941)[35]

- An jedem Finger zehn (1954)[35]

- Carosello del varietà (1955)[35]

Documentaries[]

- Joséphine Baker. Black Diva in a White Man’s World. Film by Annette von Wangenheim, about Baker’s life and work from a perspective that analyses images of Black people in popular culture, WDR/3sat, 2006

- Joséphine Baker: Black Diva in a White Man’s World. Film by Annette von Wangenheim, Trailer – ArtMattan Films

References[]

- ^ Atwood, Kathryn (2011). Women Heroes of World War II. Chicago Review Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1556529610.

- ^ Kelleher, Katy (26 March 2010). "She'll Always Have Paris". Jezebel. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bostock, William W. (2002). "Collective Mental State and Individual Agency: Qualitative Factors in Social Science Explanation". Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung. 3 (3). ISSN 1438-5627. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ Roberts, Kimberly (8 April 2011). "Remembering Josephine Baker". Philadelphia Tribune.

- ^ "Josephine Baker: The life of an artist and activist". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Baker, Jean-Claude (1993). Josephine: The Hungry Heart (First ed.). Random House. ISBN 978-0679409151.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bouillon, Joe (1977). Josephine (First ed.). Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060102128.

- ^ "Josephine Baker to Become First Black Woman to Enter France's Pantheon". hollywoodreporter.com. The Hollywood Reporter. 23 August 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ "Josephine Baker (Freda McDonald) Native of St. Louis, Missouri". Black Missouri. 10 February 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ "About Art Deco – Josephine Baker". Victoria and Albert Museum. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2009.

- ^ "About Josephine Baker: Biography". Official site of Josephine Baker. 2008. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ Wood, Ian (2000). The Josephine Baker Story. United Kingdom: MPG Books. pp. 241–318. ISBN 978-1860742866.

- ^ 1920 United States Federal Census

- ^ Whitaker, Matthew C. (2011). Icons of Black America: Breaking Barriers and Crossing Boundaries. p. 64.

- ^ "The Rise and Fall of Josephine Baker". Dollars & Sense. 13. 1987.

- ^ Keyes, Allison. "The East St. Louis Race Riot Left Dozens Dead, Devastating a Community on the Rise". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Racial memory: Clear as black and white". St. Louis Public Radio. 27 June 2008. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ Matthews, Dasha (26 February 2018). "The Activism of Josephine Baker". UMKC Women's Center. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Nicole, Corinna (6 July 2016). "When Frida Kahlo Set Her Eyes on Josephine Baker". Owlcation. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Appel, Jacob M. (2 May 2009). St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture.

- ^ Webb, Shawncey (2016). "Josephine Baker". Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia – via Research Starters, EBSCOhost.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jules-Rosette, Bennetta (2007). Josephine Baker in Art and Life. Chicago: Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252074127.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ralling, Christopher (1987). Chasing a Rainbow: The Life of Josephine Baker.

- ^ Kirchner, Bill, ed. (2000). The Oxford Companion to Jazz. Oxford University Press. p. 700. ISBN 978-0195125108.

- ^ Williams, Iain Cameron. Underneath a Harlem Moon ... The Harlem to Paris Years of Adelaide Hall, Continuum Int. Publishing (2003); ISBN 0826458939:

- Underneath A Harlem Moon by Iain Cameron Williams ISBN 0-8264-5893-9

- Stephen Bourne (24 January 2003). "The real first lady of jazz". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ^ Broughton, Sarah (2009). Josephine Baker: The First Black Superstar.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "About Josephine Baker: Biography". Official Josephine Baker website. The Josephine Baker Estate. 2008. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ "Le Jazz-Hot: The Roaring Twenties", in William Alfred Shack's Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story Between the Great Wars, University of California Press, 2001, p. 35.[ISBN missing]

- ^ "From the archive, 26 August 1974: An interview with Josephine Baker". The Guardian. 26 August 2015.

- ^ ""Quotes": the official Josephine Baker website". Cmgww.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Lahs-Gonzales, Olivia.Josephine Baker: Image & Icon (excerpt in Jazz Book Review, 2006). Archived 25 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "From the archive, 26 August 1974: An interview with Josephine Baker". The Guardian. 26 August 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Esha. "Josephine Baker in Yugoslavia". historicly.substack.com. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2013). The African American People: A Global History. Routledge. p. 277. ISBN 978-1136506772.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f McCann, Bob (2009). Encyclopedia of African American Actresses in Film and Television. p. 31. ISBN 978-0786458042.

- ^ "Josephine Baker: The First Black Super Star". Allblackwoman.com. 4 June 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schroeder, Alan and Heather Lehr Wagner (2006). Josephine Baker: Entertainer. Chelsea House Publications. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0791092125.

- ^ Cullen, Frank (2006). Vaudeville, Old and New: An Encyclopedia of Variety Performers in America, 2 volumes. Routledge. p. 235. ISBN 978-0415938532.

- ^ Susan Robinson (3 June 1906). "Josephine Baker". Gibbs Magazine. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Rose, Phyllis (1989). Jazz Cleopatra: Josephine Baker in her time. United States: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385248914.

- ^ "Female Spies in World War I and World War II". About.com. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Ann Shaffer (4 October 2006). "Review of Josephine Baker: A Centenary Tribute". blackgrooves. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ Joyce, Dr Robin (5 March 2017). "Josephine Baker, 1906–1975". Women's History Network. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ "Josephine Baker hero | Heroes: What They Do & Why We Need Them". University of Richmond. 25 May 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Reed, Tom (1992). The Black music history of Los Angeles, its roots: 50 years in Black music: a classical pictorial history of Los Angeles Black music of the 20's, 30's, 40's, 50's and 60's : photographic essays that define the people, the artistry and their contributions to the wonderful world of entertainment (1st, limited ed.). Los Angeles: Black Accent on L.A. Press. ISBN 096329086X. OCLC 28801394.

- ^ "Josephine Baker to Crown Queen" Headliner Los Angeles Sentinel 22 May 1952.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hinckley, David (9 November 2004). "Firestorm Incident At The Stork Club, 1951". New York Daily News. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "Stork Club Refused to Serve Her, Josephine Baker Claims". Milwaukee Journal. 19 October 1951. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ Spoto, Donald (2009). High Society: The Life of Grace Kelly. New York: Harmony Books. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-307-46251-0. OCLC 496121174.

- ^ Kissel, Howard (3 May 2000). "Stork Club Special Delivery Exhibit at the New York Historical Society recalls a glamour gone with the wind". Daily News. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dittmer 1994, p. 21.

- ^ Rustin, Bayard (28 February 2006). "Profiles in Courage for Black History Month". National Black Justice Coalition. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ "Civil Rights March on Washington". Infoplease.com. 28 August 1963. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Baker, Josephine; Bouillon, Joe (1977). Josephine (First ed.). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0060102128.

- ^ "March on Washington had one female speaker: Josephine Baker". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ "(1963) Josephine Baker, "Speech at the March on Washington" | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". www.blackpast.org. 3 November 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Garber, Marjorie. Bisexuality and the Eroticism of Everyday Life. Routledge, 2013, p. 122. ISBN 978-0415926614

- ^ Assouline, P. Simenon, A Biography. Knopf (1997), pp. 74–75; ISBN 0679402853.

- ^ "Josephine Baker". cmgww.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ Strong, Lester Q. (2006). "Baker, Josephine (1906–1975)" (PDF). GLBTQ Archive. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ "Biography". Josephine Baker Estate. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ Onion, Rebecca (18 April 2014). "Josephine Baker's Rainbow Tribe". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Guterl, Matthew Pratt (19 April 2014). "Would the perfect family contain a child from every race?". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Stephen Papich, Remembering Josephine. p. 149

- ^ "Josephine Baker Biography". Women in History. 2008. Archived from the original on 18 January 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ "Baker Children".

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Josephine Baker", Notable Black American Women, Gale, 1992.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Guterl, Matthew (2014). Josephine Baker and the Rainbow Tribe. Belknap Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0674047556.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "African American Celebrity Josephine Baker, Dancer and Singer". AfricanAmericans.com. 2008. Archived from the original on 2 January 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ Staff writers (13 April 1975). "Josephine Baker Is Dead in Paris at 68". The New York Times. p. 60. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ "Josephine Baker Biography - life, name, school, mother, old, information, born, husband, house, time, year". Notablebiographies.com. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ Ara, Konomi (30 March 2010). "Josephine Baker: A Chanteuse and a Fighter". Journal of Transnational American Studies. 2 (1). doi:10.5070/T821006983. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ Johnson Publishing Company (15 May 1975). "Jet". Jet : 2004. Johnson Publishing Company: 28–. ISSN 0021-5996.

- ^ Verany, Cedric (1 November 2008). "Monaco Cimetière: des bornes interactives pour retrouver les tombes". Monaco Matin. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Visite funéraire de Monaco". Amis et Passionés du Père-Lachaise. 30 August 2005. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ "Hall of Famous Missourians, Missouri House of Representatives". House.mo.gov. 29 March 1995. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ Lab, Missouri Historical Society | Mohistory. "Junction of Channing Avenue (Josephine Baker Boulevard) with Lindell Boulevard and Olive Street". The Missouri Historical Society is ... Missouri Historical Society and was founded in 1866. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Legacy Walk unveils five new bronze memorial plaques - 2342 - Gay Lesbian Bi Trans News". Windy City Times. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Piscine Joséphine Baker, paris.fr; accessed 3 June 2017.(in French)

- ^ "What do twerking and the Charleston have in common?". BBC Magazine Monitor. 17 November 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ "Chez Josephine". Jean-Claude Baker. 2009. Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- ^ Crosley, Sloane (12 July 2016). "Exploring the France That Josephine Baker Loved". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Milne, Andrew (29 October 2019). "Spend a day with Josephine Baker in her beloved château". Explore France. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kraut, Anthea (Summer 2008). "Review: Josephine Baker in Art and Life: The Icon and the Image by Bennetta Jules-Rosette". Dance Research Journal. 40 (1): 83–86. doi:10.1017/S014976770000139X. JSTOR 20527595. S2CID 191289759.

- ^ Morgan Jerkins (3 June 2016). "90 Years Later, the Radical Power of Josephine Baker's Banana Skirt". Vogue. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Madeleine Buxton (3 June 2017). "Google Doodle Honors Jazz Age Icon & Civil Rights Activist Josephine Baker". Refinery 29. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ <"Josephine Baker: The Story of an Awakening". Retrieved 15 October 2019.

- ^ Barmann, Jay (2 September 2014). "Castro's Rainbow Honor Walk Dedicated Today". SFist. SFist. Archived from the original on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Bajko, Matthew S. (5 June 2019). "Castro to see more LGBT honor plaques". The Bay Area Reporter. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Yollin, Patricia (6 August 2019). "Tributes in Bronze: 8 More LGBT Heroes Join S.F.'s Rainbow Honor Walk". KQED: The California Report. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Petition seeks to honour French Resistance hero Joséphine Baker at the Panthéon". France 24. 30 May 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "Musical legend Josephine Baker to enter France's Pantheon". France 24. 22 August 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "First black woman to enter French Panthéon of heroes". BBC News. 23 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "Alexander Calder. Josephine Baker (III). Paris, c. 1927 | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Es muss nicht immer Kaviar sein". The New York Times Book Review. 70: 150. 1965.

- ^ "An Evening With Diana Ross (1977)". dianarossproject. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "Joséphine Baker baila en ... Das boot". YouTube. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "Biography – Helen Gelzer". danforthmusic.net. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ Helen Gelzer as 'Josephine': the concept musical. worldcat.org. 1986. OCLC 058782854.

- ^ Jack Hockett – Josephine Baker correspondence, etc., (dated 1967–1976) part of the Henry Hurford Janes – Josephine Baker Collection at Yale University Archives, Box: 2, Folder: 78 Jack Hockett correspondence

- ^ (in French) Africultures.com

- ^ "Anastasia-Paris Hold the Key (to Your Heart) Original". YouTube. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "FRIDA". Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1 November 2002). "Frida". roger ebert. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "The Triplets of Belleville (Les Triplettes de Belleville)". bonjourparis.com. August 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Campion, Angela (2004). Scandalous. Brown Skin Books. ISBN 978-0954486624.

- ^ Scheib, Ronnie (13 March 2009). "Review: 'Carmen and Geoffrey'". Variety. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ "Langston Hughes African American Film Festival 2009: Carmen and Geoffrey". bside.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ "Legend Josephine Baker passes away and Vince Gill is born". citybeat.com. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "À la recherche de Joséphine". paris-tourist.com. 25 November 2006. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "Joséphine Baker". Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Clement, Olivia (11 May 2016). "The Verdict: What Do Critics Think of Josephine?". Playbill. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ "Keri Hilson Pays Tribute To Janet, TLC, Supremes In 'Pretty Girl Rock' Video". yahoo music. 17 November 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "The characters referenced in Woody Allen's Midnight in Paris (Part 16, Josephine Baker)". thedailyhatch.org. 24 June 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Hammond, Margo (29 July 2011). "A 'Midnight in Paris' tour takes you back to the Paris of the '20s". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Anderson-Randolph, Peggi Eve (2012). Josephine's Incredible Shoe and the Blackpearls (Volume 1). ISBN 978-1477570159.

- ^ "Latest News". The Sensational Josephine Baker. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "The Sensational Josephine Baker". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ "Bush Theatre". Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ "Josephine and I", publictheater.org; accessed 13 October 2016.

- ^ "Home". Josephine the play. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ "The Lost Generation". IMDB.

- ^ "The Last Night of Josephine Baker". OutSmart Magazine. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Laird, Gary (27 February 2017). "BWW Review: Josephine Reigns Supreme in 'The Last Night of Josephine Baker' at Midtown Arts Center". Broadway World Houston. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ "The Ensemble Theatre Elevates the Life of Josephine Baker in Season Finale Musical "Josephine Tonight"". Houston Style Magazine. 12 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ "'Lovecraft Country' Recap: Shoot the Moon". Rolling Stone. 27 September 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "La Sirene Des Tropiques". yahoo movies. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ De Baroncelli, Jacques, The French Way – Josephine Baker, retrieved 18 January 2019

Bibliography[]

- The Josephine Baker collection, 1926–2001 at Stanford University Libraries

- Atwood, Kathryn J., & Sarah Olson. Women Heroes of World War II: 26 Stories of Espionage, Sabotage, Resistance, and Rescue. Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Review Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1556529610

- Baker, J.C., & Chris Chase (1993). Josephine: The Hungry Heart. New York: Random House. ISBN 0679409157

- Baker, Jean-Claude, & Chris Chase (1995). Josephine: The Josephine Baker Story. Adams Media Corp. ISBN 1558504729

- Baker, Josephine, & Jo Bouillon (1995). Josephine. Marlowe & Co. ISBN 1569249784

- Bonini, Emmanuel (2000). La veritable Josephine Baker. Paris: Pigmalean Gerard Watelet. ISBN 2857046162

- Dittmer, John (1994) Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, ISBN 0252065077

- Guterl, Matthew, Josephine Baker and the Rainbow Tribe Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0674047556

- Hammond O'Connor, Patrick (1988). Josephine Baker. Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0224024418

- Haney, Lynn (1996). Naked at the Feast: A Biography of Josephine Baker. Robson Book Ltd. ISBN 0860519651

- Jules-Rosette, Bennetta (2007). Josephine Baker in Art and Life: The Icon and the Image. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252074122

- Jules-Rosette, Bennetta (2006). Josephine Baker: Image and Icon. Reedy Press. ISBN 1933370025

- Kraut, Anthea, "Between Primitivism and Diaspora: The Dance Performances of Josephine Baker, Zora Neale Hurston, and Katherine Dunham", Theatre Journal 55 (2003): 433–50.

- Mackrell, Judith. Flappers: Six Women of a Dangerous Generation. 2013. ISBN 978-0330529525

- Mahon, Elizabeth Kerri (2011). Scandalous Women: The Lives and Loves of History's Most Notorious Women. Perigee Trade. ISBN 0399536450

- Rose, Phyllis (1991). Jazz Cleopatra: Josephine Baker in Her Time. Vintage. ISBN 0679731334

- Schroeder, Alan (1989). Ragtime Tumpie. Little, Brown; an award-winning children's picture book about Baker's childhood in St. Louis and her dream of becoming a dancer.[ISBN missing]

- Schroeder, Alan (1990). Josephine Baker. Chelsea House. ISBN 079101116X, a young-adult biography.

- Theile, Merlind. "Adopting the World: Josephine Baker's Rainbow Tribe" Spiegel Online International, 2 October 2009.

- Williams, Iain Cameron. Underneath a Harlem Moon: The Harlem to Paris Years of Adelaide Hall. Bloomsbury Publishers, ISBN 0826458939 The book contains documentation of the rivalry between Adelaide Hall and Josephine Baker.

- Wood, Ean (2002). The Josephine Baker Story. Sanctuary Publishing; ISBN 1860743943

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Josephine Baker |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Josephine Baker. |

- Josephine Baker at the Casino de Paris, 1931 at YouTube

- Official website

- Les Milandes – Josephine Baker's castle in France

- Josephine Baker at AllMusic

- Josephine Baker at the Internet Broadway Database

- Josephine Baker at IMDb (self)

- Josephine Baker at Find a Grave

- Portraits of Josephine Baker at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- A Josephine Baker photo gallery

- Josephine Baker at the Red Hot Jazz Archive

- "Discography at Sony BMG Masterworks". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- Photographs of Josephine Baker

- The electric body: Nancy Cunard sees Josephine Baker (2003) – review essay of dance style and contemporary critics

- Guide to Josephine Baker papers at Houghton Library, Harvard University

- "Josephine Baker photographs". University of Missouri–St. Louis.

- Norwood, Arlisha. "Josephine Baker". National Women's History Museum. 2017.

- Josephine Baker paper at the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

- Finding aid to the Josephine Baker collection at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- African-American female singers

- American emigrants to France

- American female erotic dancers

- American burlesque performers

- Cabaret singers

- 1906 births

- 1975 deaths

- Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur

- Female recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France)

- Actresses from St. Louis

- Anti-racism activists

- Bisexual actresses

- Bisexual musicians

- Burials in Monaco

- Columbia Records artists

- Converts to Roman Catholicism

- Deaths by intracerebral hemorrhage

- Disease-related deaths in France

- Female resistance members of World War II

- French buskers

- French female erotic dancers

- French film actresses

- French-language singers of the United States

- French people of African-American descent

- French Resistance members

- French Roman Catholics

- French spies

- French vedettes

- Black French musicians

- Harlem Renaissance

- LGBT dancers

- LGBT singers from France

- LGBT people from Missouri

- LGBT singers from the United States

- LGBT Roman Catholics

- LGBT African Americans

- Mercury Records artists

- Music hall performers

- Naturalized citizens of France

- People from St. Louis

- Former United States citizens

- RCA Victor artists

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France)

- Recipients of the Resistance Medal

- Traditional pop music singers

- Vaudeville performers

- French women in World War II

- 20th-century French actresses

- 20th-century French singers

- French Freemasons

- 20th-century American women singers

- 20th-century American singers

- Female wartime spies

- African-American Catholics

- 20th-century LGBT people

WikiMiniAtlas

WikiMiniAtlas