Jungian archetypes

Jungian archetypes are defined as universal, primal symbols and images that derive from the collective unconscious, as proposed by Carl Jung. They are the psychic counterpart of instinct. It is described as a kind of innate unspecific knowledge, derived from the sum total of human history, which prefigures and directs conscious behavior. They are underlying base forms, or the archetypes-as-such, from which emerge images and motifs[4] such as the mother, the child, the trickster, and the flood among others. History, culture, and personal context shape these manifest representations thereby giving them their specific content. These images and motifs are more precisely called archetypal images. However, it is common for the term archetype to be used interchangeably to refer to both the base archetypes-as-such and the culturally specific archetypal images.[5]

Archetypes, according to Jung, seek actualization within the context of an individual's environment and determine the degree of individuation. For example, the mother archetype is actualized in the mind of the child by the evoking of innate anticipations of the maternal archetype when the child is in the proximity of a maternal figure who corresponds closely enough to its archetypal template. This mother archetype is built into the personal unconscious of the child as a mother complex. Complexes are functional units of the personal unconscious, in the same way that archetypes are units for the collective unconscious.

Critics have accused Jung of metaphysical essentialism. His psychology, particularly his thoughts on spirit, lacked necessary scientific basis, making it mystical and based on foundational truth.[6] Since archetypes are defined so vaguely and since archetypal images are an essentially infinite variety of everyday phenomena, they are neither generalizable nor specific in a way that may be researched or demarcated with any kind of rigor. Hence they elude systematic study. Feminist critiques have focused on aspects that are seen as being reductionistic and provide a stereotyped view of femininity and masculinity.[7] Other critics respond that archetypes do nothing more than to solidify the cultural prejudices of the interpreter.[8]

Jung was a psychiatrist and intended for archetypes to be a tool in psychiatry, to understand people and their drives better. However, archetypes saw little uptake within the discipline, and few modern psychiatrists consider them relevant. They did, however, succeed in gaining relevance among both literary and metaphysical circles. Archetypal literary criticism helped influence numerous works of fiction inspired by Jung's archetypes, and more spiritually inclined followers saw the archetypes as reflecting deep cross-cultural metaphysical truths.

Introduction[]

Carl Jung rejected the tabula rasa theory of human psychological development. He proposed that thoughts, connections, behaviors, and feelings exist within the human race such as belonging, love, death, and fear, among others.[9] These constitute what Jung called the "collective unconscious" and the concept of archetypes underpins this notion.[9] He believed that evolutionary pressures have individual predestinations manifested in archetypes.[10] He introduced the first understanding of this concept when he coined the term primordial images. Jung would later use the term "archetypes".

According to Jung, archetypes are inherited potentials that are actualized when they enter consciousness as images or manifest in behavior on interaction with the outside world.[5] They are autonomous and hidden forms that are transformed once they enter consciousness and are given particular expression by individuals and their cultures. In Jungian psychology, archetypes are highly developed elements of the collective unconscious. The existence of archetypes may be inferred from stories, art, myths, religions, or dreams.[11]

Jung's idea of archetypes was based on Immanuel Kant's categories, Plato's Ideas, and Arthur Schopenhauer's prototypes.[12] For Jung, "the archetype is the introspectively recognizable form of a priori psychic orderedness".[13] "These images must be thought of as lacking in solid content, hence as unconscious. They only acquire solidity, influence, and eventual consciousness in the encounter with empirical facts."[14] They are, however, distinguished from Plato's Ideas, in the sense that they are dynamic and goal-seeking properties, actively seeking actualization both in the personality and behavior of an individual as his life unfolds in the context of the environment.[15]

The archetypes form a dynamic substratum common to all humanity, upon the foundation of which each individual builds his own experience of life, colouring them with his unique culture, personality, and life events. Thus, while archetypes themselves may be conceived as a relative few innate nebulous forms, from these may arise innumerable images, symbols, and patterns of behavior. While the emerging images and forms are apprehended consciously, the archetypes which inform them are elementary structures that are unconscious and impossible to apprehend.[16][17]

Jung was fond of comparing the form of the archetype to the axial system of a crystal, which preforms the crystalline structure of the mother liquid, although it has no material existence of its own. This first appears according to the specific way in which the ions and molecules aggregate. The archetype in itself is empty and purely formal: a possibility of representation which is given a priori. The representations themselves are not inherited, only the forms, and in that respect they correspond to the instincts. The existence of the instincts can no more be proved than the existence of the archetypes, so long as they do not manifest themselves concretely.[18]

With respect to defining terms and exploring their natures, a study published in the journal Psychological Perspective in 2017 stated that the Jungian representations find expression through a wide variety of human experiences, the article summing up,

"Archetypes are universal organizing themes or patterns that appear regardless of space, time, or person. Appearing in all existential realms and at all levels of systematic recursion, they are organized as themes in the unus mundus, which Jung... described as “the potential world outside of time,” and are detectable through synchronicities."[19]

Early development[]

The intuition that there was more to the psyche than individual experience possibly began in Jung's childhood. The very first dream he could remember was that of an underground phallic god. Later in life, his research on psychotic patients in Burgholzli Hospital and his own self-analysis later supported his early intuition about the existence of universal psychic structures that underlie all human experience and behavior. Jung first referred to these as "primordial images" – a term he borrowed from Jacob Burckhardt. Later in 1917, Jung called them "dominants of the collective unconscious."[20]

It was not until 1919 that he first used the term "archetypes"[21] in an essay titled "Instinct and the Unconscious". The first element in Greek 'arche' signifies 'beginning, origin, cause, primal source principle', but it also signifies 'position of a leader, supreme rule and government' (in other words a kind of 'dominant'): the second element 'type' means 'blow and what is produced by a blow, the imprint of a coin ...form, image, prototype, model, order, and norm', ...in the figurative, modern sense, 'pattern underlying form, primordial form'.[22]

Later development[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (April 2020) |

In later years Jung revised and broadened the concept of archetypes even further, conceiving of them as psycho-physical patterns existing in the universe, given specific expression by human consciousness and culture. This was part of his attempt to link depth psychology to the larger scientific program of the twentieth century.[23]

Jung proposed that the archetype had a dual nature: it exists both in the psyche and in the world at large. He called this non-psychic aspect of the archetype the "psychoid" archetype and is described as the progressive synthesis of instinct and spirit.[24] This archetype, which was developed with the help of the Austrian quantum physicist, Wolfgang Pauli, are psycho-physical patterns that are not accessible to consciousness.[25] Pauli, himself, believed that the psychoid archetype is important in understanding the principles on which the universe was created.[5] According to Jung, this archetype must be considered a continuum that includes what he previously cited as "archetypal tendency" or the innate pattern of action.[24]

Jung drew an analogy between the psyche and light on the electromagnetic spectrum. The center of the visible light spectrum (i.e., yellow) corresponds to consciousness, which grades into unconsciousness at the red and blue ends. Red corresponds to basic unconscious urges, and the invisible infra-red end of the near visual spectrum corresponds to the influence of biological instinct, which merges with its chemical and physical conditions. The blue end of the spectrum represents spiritual ideas; and the archetypes, exerting their influence from beyond the visible, correspond to the invisible realm of ultra-violet.[26] In the analogy, violet is considered a compound of red and blue but a color in its own right in the spectrum.[24] Jung suggested that not only do the archetypal structures govern the behavior of all living organisms, but that they were contiguous with structures controlling the behavior of inorganic matter as well.[27]

The archetype was not merely a psychic entity, but more fundamentally, a bridge to matter in general.[26] Jung used the term unus mundus to describe the unitary reality which he believed underlay all manifest phenomena. He conceived archetypes to be the mediators of the unus mundus, organizing not only ideas in the psyche, but also the fundamental principles of matter and energy in the physical world.[citation needed]

It was this psychoid aspect of the archetype that so impressed Nobel laureate physicist Wolfgang Pauli. Embracing Jung's concept, Pauli believed that the archetype provided a link between physical events and the mind of the scientist who studied them. In doing so he echoed the position adopted by German astronomer Johannes Kepler. Thus the archetypes that ordered our perceptions and ideas are themselves the product of an objective order that transcends both the human mind and the external world.[5]

Ken Wilber developed a theory called Spectrum of Consciousness that expanded the Jungian archetypes,[28] which he said were not used in the same way the ancient mystics (e.g. Plato and Augustine) used them.[29] He also drew from mystical philosophy to describe a fundamental state of reality where all subsequent and lower forms emerge.[30] For Wilber, these forms are actual or real archetypes and emerged out of the Emptiness or the fundamental state of reality.[30] In Eye to Eye: The Quest for the New Paradigm, Wilber clarified that the lower structures are not the archetypes but they are archetypically or collectively given.[31] He also explained that levels of forms is part of the psychological development where a higher order emerges through a differentiation of proceeding.[32]

Examples[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (April 2020) |

Jung described archetypal events: birth, death, separation from parents, initiation, marriage, the union of opposites; archetypal figures: great mother, father, child, devil, god, wise old man, wise old woman, the trickster, the hero; and archetypal motifs: the apocalypse, the deluge, the creation.[33] Although the number of archetypes is limitless,[34] there are a few particularly notable, recurring archetypal images, "the chief among them being" (according to Jung) "the shadow, the wise old man, the child, the mother ... and her counterpart, the maiden, and lastly the anima in man and the animus in woman".[35][36] Alternatively he would speak of "the emergence of certain definite archetypes ... the shadow, the animal, the wise old man, the anima, the animus, the mother, the child".[37]

The self designates the whole range of psychic phenomena in man. It expresses the unity of the personality as a whole.[38]

The shadow is a representation of the personal unconscious as a whole and usually embodies the compensating values to those held by the conscious personality. Thus, the shadow often represents one's dark side, those aspects of oneself that exist, but which one does not acknowledge or with which one does not identify.[39]

The anima archetype appears in men and is his primordial image of woman. It represents the man's sexual expectation of women, but also is a symbol of a man's possibilities, his contrasexual tendencies. The animus archetype is the analogous image of the masculine that occurs in women.[citation needed]

Any attempt to give an exhaustive list of the archetypes, however, would be a largely futile exercise since the archetypes tend to combine with each other and interchange qualities making it difficult to decide where one archetype stops and another begins. For example, qualities of the shadow archetype may be prominent in an archetypal image of the anima or animus. One archetype may also appear in various distinct forms, thus raising the question of whether four or five distinct archetypes should be said to be present or merely four or five forms of a single archetype.[39]

Conceptual difficulties[]

Popular and new-age uses have often condensed the concept of archetypes into an enumeration of archetypal figures such as the hero, the goddess, the wise man and so on. Such enumeration falls short of apprehending the fluid core concept. Strictly speaking, archetypal figures such as the hero, the goddess and the wise man are not archetypes, but archetypal images which have crystallized out of the archetypes-as-such: as Jung put it, "definite mythological images of motifs ... are nothing more than conscious representations; it would be absurd to assume that such variable representations could be inherited", as opposed to their deeper, instinctual sources – "the 'archaic remnants', which I call 'archetypes' or 'primordial images'".[40]

However, the precise relationships between images such as, for example, "the fish" and its archetype were not adequately explained by Jung. Here the image of the fish is not strictly speaking an archetype. The "archetype of the fish" points to the ubiquitous existence of an innate "fish archetype" which gives rise to the fish image. In clarifying the contentious statement that fish archetypes are universal, Anthony Stevens explains that the archetype-as-such is at once an innate predisposition to form such an image and a preparation to encounter and respond appropriately to the creature per se. This would explain the existence of snake and spider phobias, for example, in people living in urban environments where they have never encountered either creature.[5]

The confusion about the essential quality of archetypes can partly be attributed to Jung's own evolving ideas about them in his writings and his interchangeable use of the term "archetype" and "primordial image". Jung was also intent on retaining the raw and vital quality of archetypes as spontaneous outpourings of the unconscious and not to give their specific individual and cultural expressions a dry, rigorous, intellectually formulated meaning.[41]

Actualization and complexes[]

Archetypes seek actualization the individual live out his life cycle within the context of his environment. According to Jung, this process is called individuation, which he described as "an expression of that biological process - simple or complicated as the case may be - by which every living thing becomes what it was destined to become from the beginning".[42] It is considered a creative process that activates the unconscious and primordial images through exposure to unexplored potentials of the mind.[43] Archetypes guide the individuation process towards self-realization.[44]

Jung also used the terms "evocation" and "constellation" to explain the process of actualization. Thus for example, the mother archetype is actualized in the mind of the child by the evoking of innate anticipations of the maternal archetype when the child is in the proximity of a maternal figure who corresponds closely enough to its archetypal template. This mother archetype is built into the personal unconscious of the child as a mother complex. Complexes are functional units of the personal unconscious, in the same way that archetypes are units for the collective unconscious.[22]

Stages of life[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (April 2020) |

Archetypes are innate universal pre-conscious psychic dispositions, allowing humans to react in a human manner[45] as they form the substrate from which the basic themes of human life emerge. The archetypes are components of the collective unconscious and serve to organize, direct and inform human thought and behaviour. Archetypes hold control of the human life cycle.[33]

As we mature the archetypal plan unfolds through a programmed sequence which Jung called the stages of life. Each stage of life is mediated through a new set of archetypal imperatives which seek fulfillment in action. These may include being parented, initiation, courtship, marriage and preparation for death.[46]

"The archetype is a tendency to form such representations of a motif – representations that can vary a great deal in detail without losing their basic pattern ... They are indeed an instinctive trend".[47] Thus, "the archetype of initiation is strongly activated to provide a meaningful transition ... with a 'rite of passage' from one stage of life to the next":[48][49] such stages may include being parented, initiation, courtship, marriage and preparation for death.[50]

General developments in the concept[]

Claude Lévi-Strauss was an advocate of structuralism in anthropology. In his approach to the structure and meaning of myth, Levi-Strauss concluded that present phenomena are transformations of earlier structures or infrastructures: 'the structure of primitive thoughts is present in our minds'.[citation needed]

The concept of "social instincts" proposed by Charles Darwin, the "faculties" of Henri Bergson and the isomorphs of gestalt psychologist Wolfgang Kohler are also arguably related to archetypes.[citation needed]

In his work in psycholinguistics, Noam Chomsky describes an unvarying pattern of language acquisition in children and termed it the language acquisition device. He refers to 'universals' and a distinction is drawn between 'formal' and 'substantive' universals similar to that between archetype as such (structure) and archetypal image.[citation needed]

Jean Piaget writes of 'schemata' which are innate and underpin perceptuo-motor activity and the acquisition of knowledge, and are able to draw the perceived environment into their orbit. They resemble archetypes by virtue of their innateness, their activity and their need for environmental correspondence.[citation needed]

Ethology and attachment theory[]

In Biological theory and the concept of archetypes, Michael Fordham considered that innate release mechanisms in animals may be applicable to humans, especially in infancy. The stimuli which produce instinctive behaviour are selected from a wide field by an innate perceptual system and the behaviour is 'released'. Fordham drew a parallel between some of Lorenz's ethological observations on the hierarchical behaviour of wolves and the functioning of archetypes in infancy.[51]

Stevens (1982) suggests that ethology and analytical psychology are both disciplines trying to comprehend universal phenomena. Ethology shows us that each species is equipped with unique behavioural capacities that are adapted to its environment and 'even allowing for our greater adaptive flexibility, we are no exception. Archetypes are the neuropsychic centres responsible for co-ordinating the behavioural and psychic repertoire of our species'. Following Bowlby, Stevens points out that genetically proref name="Stevens 2006"/>

The confusion about the essential quality of archetypes can partly be attributed to Jung's own evolving ideas about them in his writings and his interchangeable use of the term "archetype" and "primordial image". Jung was also intent on retaining the raw and vital quality of archetypes as spontaneous outpourings of the unconscious and not to give their specific individual and cultural expressions a dry, rigorous, intellectually formulated meaning.grammed behaviour is taking place in the psychological relationship between mother and newborn. The baby's helplessness, its immense repertoire of sign stimuli and approach behaviour, triggers a maternal response. And the smell, sound and shape of mother triggers, for instance, a feeding response.[51]

Biology[]

Stevens suggests that DNA itself can be inspected for the location and transmission of archetypes. As they are co-terminous with natural life they should be expected wherever life is found. He suggests that DNA is the replicable archetype of the species.[51]

Stein points out that all the various terms used to delineate the messengers – 'templates, genes, enzymes, hormones, catalysts, pheromones, social hormones' – are concepts similar to archetypes. He mentions archetypal figures which represent messengers such as Hermes, Prometheus or Christ. Continuing to base his arguments on a consideration of biological defence systems he says that it must operate in a whole range of specific circumstances, its agents must be able to go everywhere, the distribution of the agents must not upset the somatic status quo, and, in predisposed persons, the agents will attack the self.[51]

Psychoanalysis[]

Melanie Klein: Melanie Klein's idea of unconscious phantasy is closely related to Jung's archetype, as both are composed of image and affect and are a priori patternings of psyche whose contents are built from experience.[51]

Jacques Lacan: Lacan went beyond the proposition that the unconscious is a structure that lies beneath the conscious world; the unconscious itself is structured, like a language. This would suggest parallels with Jung. Further, Lacan's Symbolic and Imaginary orders may be aligned with Jung's archetypal theory and personal unconscious respectively. The Symbolic order patterns the contents of the Imaginary in the same way that archetypal structures predispose humans towards certain sorts of experience. If we take the example of parents, archetypal structures and the Symbolic order predispose our recognition of, and relation to them.[51] Lacan's concept of the Real approaches Jung's elaboration of the psychoid unconscious, which may be seen as true but cannot be directly known. Lacan posited that the unconscious is organised in an intricate network governed by association, above all 'metaphoric associations'. The existence of the network is shown by analysis of the unconscious products: dreams, symptoms, and so on.[51]

Wilfred Bion: According to Bion, thoughts precede a thinking capacity. Thoughts in a small infant are indistinguishable from sensory data or unorganised emotion. Bion uses the term proto-thoughts for these early phenomena. Because of their connection to sensory data, proto-thoughts are concrete and self-contained (thoughts-in-themselves), not yet capable of symbolic representations or object relations. The thoughts then function as preconceptions – predisposing psychosomatic entities similar to archetypes. Support for this connection comes from the Kleinian analyst Money-Kyrle's observation that Bion's notion of preconceptions is the direct descendant of Plato's Ideas.[51]

Sigmund Freud: In the Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis (1916-1917) Freud wrote: "There can be no doubt that the source [of the fantasies] lie in the instincts; but it still has to be explained why the same fantasies with the same content are created on every occasion. I am prepared with an answer that I know will seem daring to you. I believe that...primal fantasies, and no doubt a few others as well, are a phylogenetic endowment". His suggestion that primal fantasies are a residue of specific memories of prehistoric experiences have been construed as being aligned with the idea of archetypes. Laplanehe and Pontalis point out that all the so-called primal fantasies relate to the origins and that "like collective myths they claim to provide a representation of and a 'solution' to whatever constitutes an enigma for the child".[51]

Robert Langs: More recently, adaptive psychotherapist and psychoanalyst Robert Langs has used archetypal theory as a way of understanding the functioning of what he calls the "deep unconscious system".[52] Langs' use of archetypes particularly pertains to issues associated with death anxiety, which Langs takes to be the root of psychic conflict. Like Jung, Langs thinks of archetypes as species-wide, deep unconscious factors.[53]

Neurology[]

Rossi (1977) suggests that the function and characteristic between left and right cerebral hemispheres may enable us to locate the archetypes in the right cerebral hemisphere. He cites research indicating that left hemispherical functioning is primarily verbal and associational, and that of the right primarily visuospatial and apperceptive. Thus the left hemisphere is equipped as a critical, analytical, information processor while the right hemisphere operates in a 'gestalt' mode. This means that the right hemisphere is better at getting a picture of a whole from a fragment, is better at working with confused material, is more irrational than the left, and is more closely connected to bodily processes. Once expressed in the form of words, concepts and language of the ego's left hemispheric realm, however, they become only representations that 'take their colour' from the individual consciousness. Inner figures such as shadow, anima and animus would be archetypal processes having source in the right hemisphere.[51]

Henry (1977) alluded to Maclean's model of the tripartite brain suggesting that the reptilian brain is an older part of the brain and may contain not only drives but archetypal structures as well. The suggestion is that there was a time when emotional behaviour and cognition were less developed and the older brain predominated. There is an obvious parallel with Jung's idea of the archetypes 'crystallising out' over time.[51]

Literary criticism[]

Archetypal literary criticism argues that archetypes determine the form and function of literary works, and therefore, that a text's meaning is shaped by cultural and psychological myths. Archetypes are the unknowable basic forms personified or concretized in recurring images, symbols, or patterns which may include motifs such as the quest or the heavenly ascent, recognizable character types such as the trickster or the hero, symbols such as the apple or snake, or images such as crucifixion (as in King Kong, or Bride of Frankenstein) are all already laden with meaning when employed in a particular work.[51]

Psychology[]

Archetypal psychology was developed by James Hillman in the second half of the 20th century. Hillman trained at the Jung Institute and was its Director after graduation. Archetypal psychology is in the Jungian tradition and most directly related to analytical psychology and psychodynamic theory, yet departs radically. Archetypal psychology relativizes and deliteralizes the ego and focuses on the psyche (or soul) itself and the archai, the deepest patterns of psychic functioning, "the fundamental fantasies that animate all life".[54] Archetypal psychology is a polytheistic psychology, in that it attempts to recognize the myriad fantasies and myths, gods, goddesses, demigods, mortals and animals – that shape and are shaped by our psychological lives. The ego is but one psychological fantasy within an assemblage of fantasies.[citation needed]

The main influence on the development of archetypal psychology is Jung's analytical psychology. It is strongly influenced by Classical Greek, Renaissance, and Romantic ideas and thought. Influential artists, poets, philosophers, alchemists, and psychologists include: Nietzsche, Henry Corbin, Keats, Shelley, Petrarch, and Paracelsus. Though all different in their theories and psychologies, they appear to be unified by their common concern for the psyche – the soul.[citation needed]

Many archetypes have been used in treatment of psychological illnesses. Jung's first research was done with schizophrenics. A current example is teaching young men or boys archetypes through using picture books to help with the development.[55] In addition nurses treat patients through the use of archetypes.[48]

Pedagogy[]

Archetypal pedagogy was developed by Clifford Mayes. Mayes' work also aims at promoting what he calls in teachers; this is a means of encouraging teachers to examine and work with psychodynamic issues, images, and assumptions as those factors affect their pedagogical practices. More recently the (PMAI), based on Jung's theories of both archetypes and personality types, has been used for pedagogical applications (not unlike the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator).[citation needed]

Applications of archetype-based thinking[]

In historical works[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (April 2020) |

Archetypes have been cited by multiple scholars as key figures within both ancient Greek and ancient Roman culture. Characters embodying Jungian traits have additionally been observed in various works after classical antiquity in societies such as the various nations of Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire as well as the Celtic cultures of the British Isles.[citation needed]

Examples out of ancient history include the epic works Iliad and Odyssey. Specifically, scholar Robert Eisner has argued that the anima concept within Jungian thought exists in prototype form within the goddess characters in said stories. He has particularly cited Athena, for instance, as a major influence.[56]

In the context of the medieval period, British writer Geoffrey Chaucer's work The Canterbury Tales has been cited as an instance of the prominent use of Jungian archetypes. The Wife of Bath's Tale in particular within the larger collection of stories features an exploration of the bad mother and good mother concepts. The given tale's plot additionally contains broader Jungian themes around the practice of magic, the use of riddles, and the nature of radical transformation.[57]

In British intellectual and poet John Milton's epic work Paradise Lost, the character of Lucifer features some of the attributes of an archetypal hero, including courage and force of will, yet comes to embody the shadow concept in his corruption of Adam and Eve. Like the two first humans, Lucifer is portrayed as a created being meant to serve the purposes of heaven. However, his rebellion and assertions of pride sets him up philosophically as a dark mirror of Adam and Eve's initial moral obedience. As well, the first two people function as each other's anima and animus, their romantic love serving to make each other psychologically complete.[58]

In modern popular culture[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (April 2020) |

Archetypes abound in contemporary artistic expression such as films, literature, music, and video games as they have in creative works of the past, the given projections of the collective unconscious still serving to embody central societal and developmental struggles in media that entertains as well as instructs. Works made both during and after Jung's lifetime have frequently gotten subject to academic analysis in terms of their psychological aspects. Studies have evaluated material both in the narrow sense of looking at given character developments and plots as well as in the broader sense of how cultures as integrated wholes proliferate their shared beliefs.[citation needed]

Films function as a contemporary form of myth-making in particular, various works reflecting individuals' responses to themselves and the broader mysteries and wonders of human existence. The very act of watching movies has important psychological meaning not just at the individual level but additionally in terms of the sharing of mass social attitudes through common experience. Jung himself felt fascinated by the dynamics of the medium. Film criticism has long applied Jungian thought to different types of analysis, with archetypes getting seen as an important aspect of storytelling on the silver screen.[60]

A study conducted by scholars and John D. Mayer in 2009 found that certain archetypes in richly detailed media sources can be reliably identified by individuals. They stated as well that people's life experiences and personality appeared to give them a kind of psychological resonance with particular creations.[61] Jungian archetypes have additionally been cited as inflecting notions of what appears "cool", particularly in terms of youth culture. Actors such as James Dean and Steve McQueen in particular have been identified as rebellious outcasts embodying a particular sort of Jungian archetype in terms of masculinity.[62]

Contemporary cinema is a rich source of archetypal images, most commonly evidenced for instance in the hero archetype: the one who saves the day and is young and inexperienced, like Luke Skywalker in Star Wars, or older and cynical, like Rick Blaine in Casablanca. The mentor archetype is a common character in all types of films. They can appear and disappear as needed, usually helping the hero in the beginning, and then letting them do the hard part on their own. The mentor helps train, prepare, encourage and guide the hero. They are obvious in some films: Mr. Miyagi in The Karate Kid, Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings, Jiminy Cricket in Pinocchio, Obi-Wan Kenobi, and later Yoda in the original Star Wars trilogy.[citation needed]

Character Atticus Finch of To Kill a Mockingbird, named the greatest movie hero of all time by the American Film Institute,[1] fulfills in terms of archetypes three roles: the father,[2] the hero, and the idealist.[citation needed] In terms of the former, he's been described "the purest archetypal father in the movies" in terms of his close relationship to his children, providing them with instincts such as hope.[2] Other prominent characters on the silver screen and elsewhere have additionally embodied multiple archetypes.

The Shadow, one's darker side, is often associated with the villain of numerous films and books, but can be internal as in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The shapeshifter is the person who misleads the hero, or who changes frequently and can be depicted quite literally, e.g. The T-1000 robot in Terminator 2: Judgment Day. The Trickster creates disruptions of the status quo, may be childlike, and helps us see the absurdity in situations, provides comic relief, etc. (e.g. Yoda in The Empire Strikes Back, Bugs Bunny and Brer Rabbit). The Child, often innocent, could be someone childlike who needs protecting but may be imbued with special powers (e.g. E.T.). The Bad Father is often seen as a dictator type, or evil and cruel, e.g. Darth Vader in Star Wars. The Bad Mother (e.g. Mommie Dearest) is symbolized by evil stepmothers and wicked witches. The Bad Child is exemplified in The Bad Seed and The Omen.[citation needed]

Jungian archetypes are heavily integrated into the plots and personalities of the characters in the Persona series of games. In Persona 1, Persona 2: Innocent Sin, and Persona 2: Eternal Punishment, the character of Philemon is a reference to the wise spirit guide from Jung's The Red Book, and it is revealed that the personas are formed from archetypes from the collective unconsciousness. In Persona 3 onwards, the characters with whom the player forms relationships (called "Social Links" in Persona 3 and Persona 4, and "Confidants" in Persona 5), are each based on a particular archetype, in addition to tarot arcana. The collective unconscious is also represented in Persona 5 by the Mementos location.[citation needed]

In marketing, an archetype is a genre to a brand, based upon symbolism. The idea behind using brand archetypes in marketing is to anchor the brand against an icon already embedded within the conscience and subconscious of humanity. In the minds of both the brand owner and the public, aligning with a brand archetype makes the brand easier to identify. Twelve archetypes have been proposed for use with branding: Sage, Innocent, Explorer, Ruler, Creator, Caregiver, Magician, Hero, Outlaw, Lover, Jester, and Regular Person.[63]

In non-fiction[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (April 2020) |

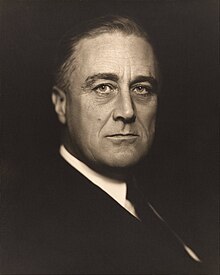

Analysis of real-life individuals as filling up Jungian roles has taken place in multiple publications. For example, American leader Franklin D. Roosevelt has been described as an archetypal father figure for his nation in the context of World War II and specifically in terms of his reassuring comments to the U.S. after events at Pearl Harbor. He can also be seen as the shapeshifter for engineering a U.S. debt default in 1933.[citation needed] An article in Psychology Today has stated generally that applying upward individual "values onto a national figure parallels how we project values and qualities onto the most important and guiding presences in our personal lives, our own mothers and fathers."[64]

Criticism[]

Jung's staunchest critics have accused him of either mystical or metaphysical essentialism. Since archetypes are defined so vaguely and since archetypal images have been observed by many Jungians in a wide and essentially infinite variety of everyday phenomena, they are neither generalizable nor specific in a way that may be researched or demarcated with any kind of rigor. Hence they elude systematic study. Jung and his supporters defended the impossibility of providing rigorous operationalised definitions as a problem peculiar not only to archetypal psychology alone, but also other domains of knowledge that seek to understand complex systems in an integrated manner.[citation needed]

Feminist critiques have focused on aspects of archetypal theory that are seen as being reductionistic and providing a stereotyped view of femininity and masculinity.[65] Modern scholarship with its emphasis on power and politics have seen archetypes as a colonial device to level the specifics of individual cultures and their stories in the service of grand abstraction. This is demonstrated in the conceptualization of the "Other", which can only be represented by limited ego fiction despite its "fundamental unfathomability".[66]

Another criticism of archetypes is that seeing myths as universals tends to abstract them from the history of their actual creation, and their cultural context.[67] Some modern critics state that archetypes reduce cultural expressions to generic decontextualized concepts, stripped bare of their unique cultural context, reducing a complex reality into something "simple and easy to grasp".[67] Other critics respond that archetypes do nothing more than to solidify the cultural prejudices of the myths interpreter – namely modern Westerners. Modern scholarship with its emphasis on power and politics have seen archetypes as a colonial device to level the specifics of individual cultures and their stories in the service of grand abstraction.[68]

Others have accused him of a romanticised and prejudicial promotion of 'primitivism' through the medium of archetypal theory. Archetypal theory has been posited as being scientifically unfalsifiable and even questioned as to being a suitable domain of psychological and scientific inquiry. Jung mentions the demarcation between experimental and descriptive psychological study, seeing archetypal psychology as rooted by necessity in the latter camp, grounded as it was (to a degree) in clinical case-work.[69]

Because Jung's viewpoint was essentially subjectivist, he displayed a somewhat Neo-Kantian perspective of a skepticism for knowing things in themselves and a preference of inner experience over empirical data. This skepticism opened Jung up to the charge of countering materialism with another kind of reductionism, one that reduces everything to subjective psychological explanation and woolly quasi-mystical assertions.[70]

Post-Jungian criticism seeks to contextualise, expand and modify Jung's original discourse on archetypes. Michael Fordham is critical of tendencies to relate imagery produced by patients to historical parallels only, e.g. from alchemy, mythology or folklore. A patient who produces archetypal material with striking alchemical parallels runs the risk of becoming more divorced than before from his setting in contemporary life.[51]

See also[]

- Archetype

- Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism

- Evolutionary psychology

- Joseph Campbell

- Monomyth

- Mythology

- Metafiction

- Narrativium

- Self-actualization

- Self-realization

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Campbell, Duncan (June 12, 2003). "Gregory Peck, screen epitome of idealistic individualism, dies aged 87". The Guardian. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Higgins, Gareth (2013). Cinematic States: Stories We Tell, the American Dreamlife, and How to Understand Everything*. Conundrum Press. ISBN 9781938633348.

- ^ Giddens, Thomas, ed. (2015). Graphic Justice: Intersections of Comics and Law. Routledge. ISBN 9781317658382.

- ^ Brugue, Lydia; Llompart, Auba (2020). Contemporary Fairy-Tale Magic: Subverting Gender and Genre. Leiden: BRILL. p. 196. ISBN 978-90-04-41898-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Stevens, Anthony in "The archetypes" (Chapter 3.) Ed. Papadopoulos, Renos. The Handbook of Jungian Psychology (2006)

- ^ Cattoi, Thomas; Odorisio, David M. (2018). Depth Psychology and Mysticism. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 72. ISBN 978-3-319-79096-1.

- ^ Singh, Greg (2014). Film After Jung: Post-Jungian Approaches to Film Theory. New York: Routledge. p. 127. ISBN 9780415430890.

- ^ Frank, Adam (2009). The Constant Fire: Beyond the Science vs. Religion Debate. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-520-25412-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weiner, Michael O.; Gallo-Silver, Les Paul (2018). The Complete Father: Essential Concepts and Archetypes. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4766-6830-7.

- ^ Stevens, Anthony (1999). On Jung: Updated Edition (2nd ed.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 215. ISBN 069101048X. OCLC 41400920.

- ^ Stevens, Anthony (2015). Living Archetypes: The selected works of Anthony Stevens. Oxon: Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-317-59562-5.

- ^ Jung and the Post-Jungians, Andrew Samuels, Routledge (1986)

- ^ C. G. Jung, Synchronicity (London 1985) p. 140

- ^ Jung 1928:Par. 300

- ^ Stevens, Anthony (2001). Jung: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-19-160668-7.

- ^ Munro, Donald; Schumaker, John F.; Carr, Stuart C. (2014). Motivation and Culture. Oxon: Routledge. p. 2027. ISBN 9780415915090.

- ^ Packer, Sharon (2010). Superheroes and Superegos: Analyzing the Minds Behind the Masks: Analyzing the Minds Behind the Masks. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-313-35536-3.

- ^ (CW 9, pt 1, para. 155)

- ^ O'Brien, John A. (2017). "The Healing of Nations". Psychological Perspectives. 60 (2): 207–214. doi:10.1080/00332925.2017.1314701. S2CID 149140098.

- ^ COMPLEX, ARCHETYPE, SYMBOL in the Psychology of C.G. Jung by Jolande Jacobi

- ^ Hoerni, Ulrich; Fischer, Thomas; Kaufmann, Bettina, eds. (2019). The Art of C.G. Jung. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-393-25487-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stevens, Anthony Archetype Revisited: an Updated Natural History of the Self. Toronto, ON.: Inner City Books, 2003. p. 74.

- ^ Cambray, Joseph; Carter, Linda (2004). Analytical Psychology: Contemporary Perspectives in Jungian Analysis. Hove: Brunner-Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 1-58391-998-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Aziz, Robert (1990). C. G. Jung's Psychology of Religion and Synchronicity. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-7914-0166-9.

- ^ Dryden, Windy; Reeves, Andrew (2013). The Handbook of Individual Therapy, Sixth Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-4462-0136-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jung, C.G. (1947/1954/1960), Collected Works vol. 8, The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche, pp. 187, 211–216 (¶384, 414–420). "Just as the 'psychic infra-red,' the biological instinctual psyche, gradually passes over into the physiology of the organism and thus merges with its chemical and physical conditions, so the 'psychic ultra-violet,' the archetype, describes a field which exhibits none of the peculiarities of the physiological and yet, in the last analysis, can no longer be regarded as psychic, although it manifests itself psychically."

- ^ Stevens, Anthony (2016). Living Archetypes: The selected works of Anthony Stevens. New York, NY: Routledge. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-138-81767-8.

- ^ Hutchison, Elizabeth D. (2019). Dimensions of Human Behavior: Person and Environment. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-5443-3929-0.

- ^ Wilber, Ken (1998). The Essential Ken Wilber. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-57062-379-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wellings, Nigel; McCormick, Elizabeth Wilde (2000). Transpersonal Psychotherapy. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4462-6615-1.

- ^ Wilber, Ken (2001). Eye to Eye: The Quest for the New Paradigm. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications. p. 218. ISBN 1-57062-249-3.

- ^ Wilber, Ken (2014). The Atman Project: A Transpersonal View of Human Development. Quest Books. ISBN 978-0-8356-3092-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Papadopoulos, Renos K. (2006). The Handbook of Jungian Psychology: Theory, Practice and Applications. New York: Routledge. pp. 84, 85. ISBN 1-58391-147-2.

- ^ Jones, Raya A.; Gardner, Leslie (2019). Narratives of Individuation. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-51470-8.

- ^ Jung, quoted in J. Jacobi, Complex, Archetype, Symbol (London 1959) p. 114

- ^ Smith, Clare (2016). Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture: Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog. London: Springer. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-137-59998-8.

- ^ C. G. Jung, Two Essays on Analytical Psychology (London 1953) p. 108

- ^ Mattoon, Mary Ann; Hinshaw, Robert (2003). Cambridge 2001: Proceedings of the Fifteenth International Congress for Analytical Psychology. Einsiedeln, Switzerland: Daimon. p. 159. ISBN 3-85630-609-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fordham, Michael Explorations Into the Self (library of Analytical Psychology) Karnac Books, 1985.

- ^ Jung, "Approaching the Unconscious" in Jung ed., Symbols p. 57

- ^ M.-L. von Franz, "Science and the unconscious", in Jung ed., Symbols p. 386 and p. 377

- ^ Stevens, Anthony (2004). Archetype Revisited: An Updated Natural History of the Self. London: Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 1-58391-108-1.

- ^ Runco, Mark A.; Pritzker, Mark A.; Pritzker, Steven R. (1999). Encyclopedia of Creativity, Volume 2 I-Z. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 539. ISBN 0-12-227077-0.

- ^ Almaas, A. H. (2000-09-05). The Pearl Beyond Price: Integration of Personality into Being, an Object Relations Approach. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-0-8348-2499-7.

- ^ Jung, Emma; Franz, Marie-Luise von (1998). The Grail Legend. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 36. ISBN 0-691-00237-1.

- ^ Papadopoulos, Renos The Handbook of Jungian Psychology 2006

- ^ C. G. Jung, "Approaching the Unconscious" in C. G. Jung ed., Man and his Symbols (London 1978) p. 58

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rancour, Patrice (1 December 2008). "Using Archetypes and Transitions Theory to Help Patients Move From Active Treatment to Survivorship". Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 12 (6): 935–940. doi:10.1188/08.CJON.935-940. PMID 19064387.

- ^ Joseph Henderson, "Ancient Myths and Modern Man", in Jung ed., Symbols p. 123

- ^ Stevens, Anthony in "The Archetypes" (Chapter 3). Papadopoulos, Renos ed. (2006). The Handbook of Jungian Psychology.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m Andrew Samuels, Jung and the Post-Jungians ISBN 0415059046, Routledge (1986)

- ^ R Langs. Fundamentals of Adaptive Psychotherapy and Counseling. (London 2004)

- ^ R Langs. Freud on a Precipice. How Freud's Fate pushed Psychoanalysis over the Edge. (Lanham MD: 2010)

- ^ Moore, in Hillman, 1991

- ^ Zambo, Debby (2007). "Using Picture Books to Provide Archetypes to Young Boys: Extending the Ideas of William Brozo". The Reading Teacher. 61 (2): 124–131. doi:10.1598/RT.61.2.2.

- ^ Eisner, Robert (1987). The Road to Daulis: Psychoanalysis, Psychology, and Classical Mythology. Syracuse University Press. pp. 75–105. ISBN 9780815602101.

- ^ Brown, Eric D. (1978). "Symbols of Transformation: A Specific Archetypal Examination of the 'Wife of Bath's Tale'". The Chaucer Review. 12 (4): 202–217. JSTOR 25093434.

- ^ Kishbaugh, Geoffrey (1 April 2016). Becoming Self: A Jungian Approach to Paradise Lost. Masters Theses (Thesis).

- ^ Allison, Scott T.; Goethals, George R. (2011). Heroes: What They Do and Why We Need Them. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–17, 199–200. ISBN 9780199739745.

- ^ Hauke, Christopher; Alister, Ian (2001). Jung and Film. Psychology Press. pp. 1–13. ISBN 9781583911334.

- ^ Faber, Michael A.; Mayer, John D. (1 June 2009). "Resonance to archetypes in media: There's some accounting for taste". Journal of Research in Personality. 43 (3): 307–322. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.11.003.

- ^ Hall, Garret (April 2013). The Jungian Psychology of Cool: Ryan Gosling and the Repurposing of Midcentury Male Rebels. Proceedings of The National Conference On Undergraduate Research (NCUR) 2013. University of Wisconsin La Crosse, WI. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.911.5375.

- ^ Mark, M., & Pearson, C. S. (2001). The hero and the outlaw: Building extraordinary brands through the power of archetypes. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kushner, Dale M. (May 31, 2018). "Fathers: Heroes, Villains, and Our Need for Archetypes". Psychology Today. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ Reed, Toni (2009). Demon-Lovers and Their Victims in British Fiction. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-9290-1.[page needed]

- ^ Rowland, Susan (1999). C.G. Jung and Literary Theory: The Challenge from Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-312-22275-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Holt, Douglas; Cameron, Douglas (2010). Cultural Strategy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958740-7.[page needed]

- ^ Adam Frank, The Constant Fire: Beyond the Science vs. Religion Debate, 1st edition, 2009

- ^ Shelburne, Walter A. (1988). Mythos and Logos in the Thought of Carl Jung: The Theory of the Collective Unconscious in Scientific Perspective. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-693-1.[page needed]

- ^ Gundry, Mark; Gundry, Mark R. (2006). Beyond Psyche: Symbol and Transcendence in C.G. Jung. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-7867-8.[page needed]

Further reading[]

| Library resources about Jungian archetypes |

- Stevens, Anthony (2006), "Chapter 3", in Papadopoulos, Renos (ed.), The Handbook of Jungian Psychology

- Jung, C. G. (1928) [1917], Two Essays on Analytical Psychology, Collected Works, 7 (2 ed.), London: Routledge (published 1966)

- Jung, C. G. (1934–1954), The Archetypes and The Collective Unconscious, Collected Works, 9 (2 ed.), Princeton, NJ: Bollingen (published 1981), ISBN 0-691-01833-2

- Jungian archetypes

- Archetypal pedagogy

- Archetypal psychology

- Analytical psychology

- History of psychiatry

- Literary archetypes

- Carl Jung